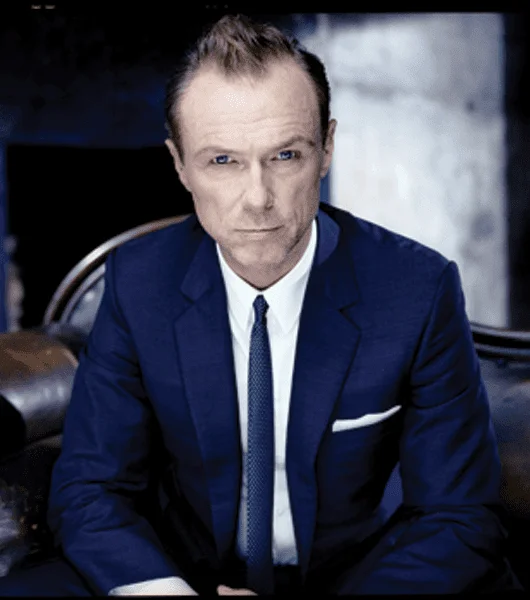

Godfathers of Pop – Dieter Meier Interview

By Classic Pop | March 26, 2015

Dapper, debonair and the son of a millionaire, Dieter Meier is the voice of Yello, the Swiss electronic-music pioneers who could be described as the missing link between Kraftwerk and Art Of Noise. Meier and musical partner Boris Blank scored their biggest successes with Oh Yeah and The Race, two of the quirkiest singles of the Eighties. The duo went on to collaborate with Shirley Bassey and the Associates vocalist Billy Mackenzie.

You’re not known as a live performer, and yet you went on stage in Montreux twice in the space of six months.

I played for Claude Nobs – who founded the Montreux Jazz Festival – when he received an award in Switzerland, six months before he passed away in January of this year. I then had the honour of playing at his memorial concert in Montreux, and I came back for the festival – not with Yello but Out Of Chaos. That name comes from the Dutch photographer Anton Corbijn, who’s a friend of mine.

He came on some video shoots with Yello and said, “This is totally chaos!” The sad irony is that Claude is no longer with us. He was always so persuasive with people and he really wanted Yello to appear at Montreux, but my partner Boris has never wanted to play live.

So why was Boris so reluctant to do concerts?

He felt that pretending to do something live, when it’s not live, would be cheating. A guitar player can relate to an audience but Boris is more like an alchemist, a painter, who takes months and years to create these incredible sounds. And he can’t do this on stage.

How would you describe your partnership with Boris?

We’ve known each other for over 30 years and we remain good friends. Our working process is like two chess players who sit in different cities and send their moves to each other. We’re not like a rock band sitting in the studio.

Why have you released so little new music recently?

We released a new CD in 2009. Things have become slower because the older you get, the more self-critical you get. When we were younger, it was a more spontaneous process to do a piece of music. But we still get tremendous enjoyment out of creating these sounds.

You pioneered sampling before Art Of Noise…

We did sampling before it was digitally possible. We just recorded a sound – such as throwing a snowball against a piece of wood – and this became a loop on a tape and the bass-drum sound on a track. The secret of our success was that we were different from anything else at the time. Neither Boris nor myself were trained musicians. We had to find our own way of expressing ourselves with sound. This gave us a certain originality because, if you can’t play the fiddle, you have to find other ways of using it.

Your videos played a big part in your success, and you had a big part in these…

I was a so-called experimental film-maker for years before Yello. I used the 16mm camera like a painter uses a brush on a canvas. Making films was an important part of my life. Before the digital age, when you made a film, you had an idea and a little script, and you used this beautiful little black box. You didn’t see the result until the film came back from the lab three days later and you screened it. It was always an adventure. I’d film a chocolate wrapper or a cup of coffee and fill the screen with it. These films weren’t telling a story – I called them moving frescos – but they became an important part of the Yello videos. They became the stage designs, the backgrounds in front of which Boris and I – these two musical clowns – would act.

You’ve been a professional poker player, you raise cattle, you make wine and you’re a performer and conceptual artist. How do you see yourself?

I’m the ultimate dilettante. People ask me to describe what I do and I don’t really like to say “artist”. I don’t even know what art is. I’m a producer of different things: the spectrum runs from organic wine to music. I could never say I did this or I’m proud of that. I’ve failed in so many things and some things have worked out.

It’s down to fate and then coincidence. Like in music, the fact that this whole style became a worldwide commodity was just luck. How could we have expected, with our tiny studio in an old factory, to sell 14 million records?