How two members of Sheffield’s most pioneering pop group split to form a new politically-driven band that would ultimately rewrite the rule book with a debut album of icy electronica and futuristic funk… Written by Mark Lindores.

Following the release of Reproduction and Travelogue, two landmark albums during the burgeoning synth-pop movement of the late-70s, The Human League’s failure to live up to their promise commercially proved to be hugely problematic for the band as the 80s dawned.

Proclaimed as “the future of pop music” by David Bowie, the Sheffield collective’s frustration that those titles languished unsold in record shops while their peers – OMD, Gary Numan and Visage had taken the sound to the top of the charts brought tensions within the band to a head.

Fearing that the pressure to have a hit would cause the group to implode, manager Bob Last engineered a split, unceremoniously ousting founding member Martyn Ware from the line-up.

“I turned up at the studio one day and they said they were throwing me out of the group,” Martyn told the BBC in 2015. “I was extremely hurt because not only were we very close as a band, Phil [Oakey] had been my best friend for years prior to that. There was an increasing amount of niggling arguments within the band – between myself and Phil in particular. But at that age we were just locking horns trying to determine who was the alpha male of the group – the founder or the lead singer. But what I didn’t know was that Bob Last and the record company had already come to the conclusion that the band wasn’t going to work and had engineered a plan to destabilise the group by dropping words in Phil’s ear, telling him he should be the star and that it should be a vehicle for straightforward pop.”

While Martyn felt betrayed and let down by his former friend and colleague, he was comforted by the loyalty of bandmate Ian Craig Marsh, who also left The Human League to work with him on the British Electric Foundation (BEF), an experimental production company on which they could collaborate with established artists and launch new projects. The pair soon recruited Glenn Gregory to complete their new music group.

Glenn had been one of Martyn’s best friends since they went to school together and was originally in the picture to front The Human League.

His decision to move to London to pursue a career in photography prevented him joining The League, but his regular retreats back home ensured he was kept abreast of what was happening on the social scene.

Gregory was a key figure on the Sheffield live music scene, frequenting the Meat Whistle arts project, the launchpad for countless groups – including Cabaret Voltaire and Clock DVA. He was back in Sheffield on a photography assignment to shoot Joe Jackson for Sounds magazine when Martyn asked him to join the band – an offer he accepted on the spot.

The friendship between Ian, Glenn and Martyn was fundamental to the instant rapport they had in the studio and set about creating their own musical manifesto. While the new-look Human League had dared to change their direction in favour of a pure pop approach, Heaven 17 decided to take a wider view and incorporate their political opinions into their music.

“It was a very political time and we wanted to address that in our music,” Gregory told the BBC. “At the same time, we still wanted it to be dance music. However, pop music and political sentiment are two entirely different things and didn’t mix, even though we wanted them to.”

Sheffield was going through an economic crisis following the deconstruction of the city’s steel industry. The buildings that once thrived with the buzz of manufacturing were often used as rental spaces for musicians, artists and filmmakers. After taking advantage of the minimal asking fees to use these disused factories and warehouses to write and demo tracks, the group’s relocation into a studio only fuelled their creativity further.

While the city may have had an abundance of rehearsal rooms and creative hubs, professional studios were scarce and Heaven 17 found themselves sharing a studio with The Human League, who were simultaneously recording their own breakthrough opus Dare.

The two bands were forced to establish a shift pattern with one recording at night, and the other taking over during the day. Sneaking a listen to what his former group had recorded, the sense of rivalry only fuelled Martyn’s own creativity.

“I was massively motivated – it was like this great explosive supernova of creativity unlike anything I’d experienced before or since,” he said.

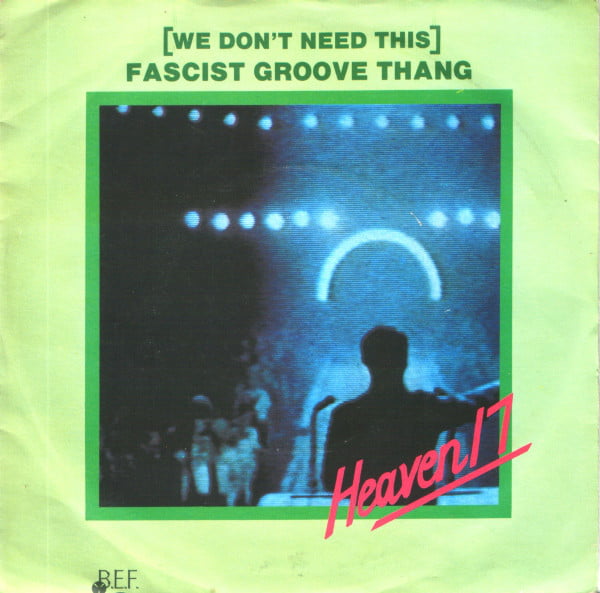

Within days, the band had written and recorded (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang, a song which would shape their musical identity, juxtaposing upbeat, dance-influenced tracks with lyrics which hammered home their political views – issues such as the arms race, nuclear war, religious extremism and the rise of the yuppie, a stance that set them apart from many of their peers.

John Wilson, a local session musician, was recruited to contribute the bass solo to Fascist Groove Thang. The result proved invaluable, not only for the song, but to the whole way the group wrote music – Ware later said meeting John alongside the invention of the Linn LM-1 drum machine were the two most significant occurrences during making the album. Wilson’s accomplished ability as a rhythm guitarist allowed them to be more adventurous in their songwriting and created an entirely new avenue for them to explore.

Material recorded with Wilson had a new wave warmth and a more varied sound than the sparse electronics they had previously restricted themselves to.

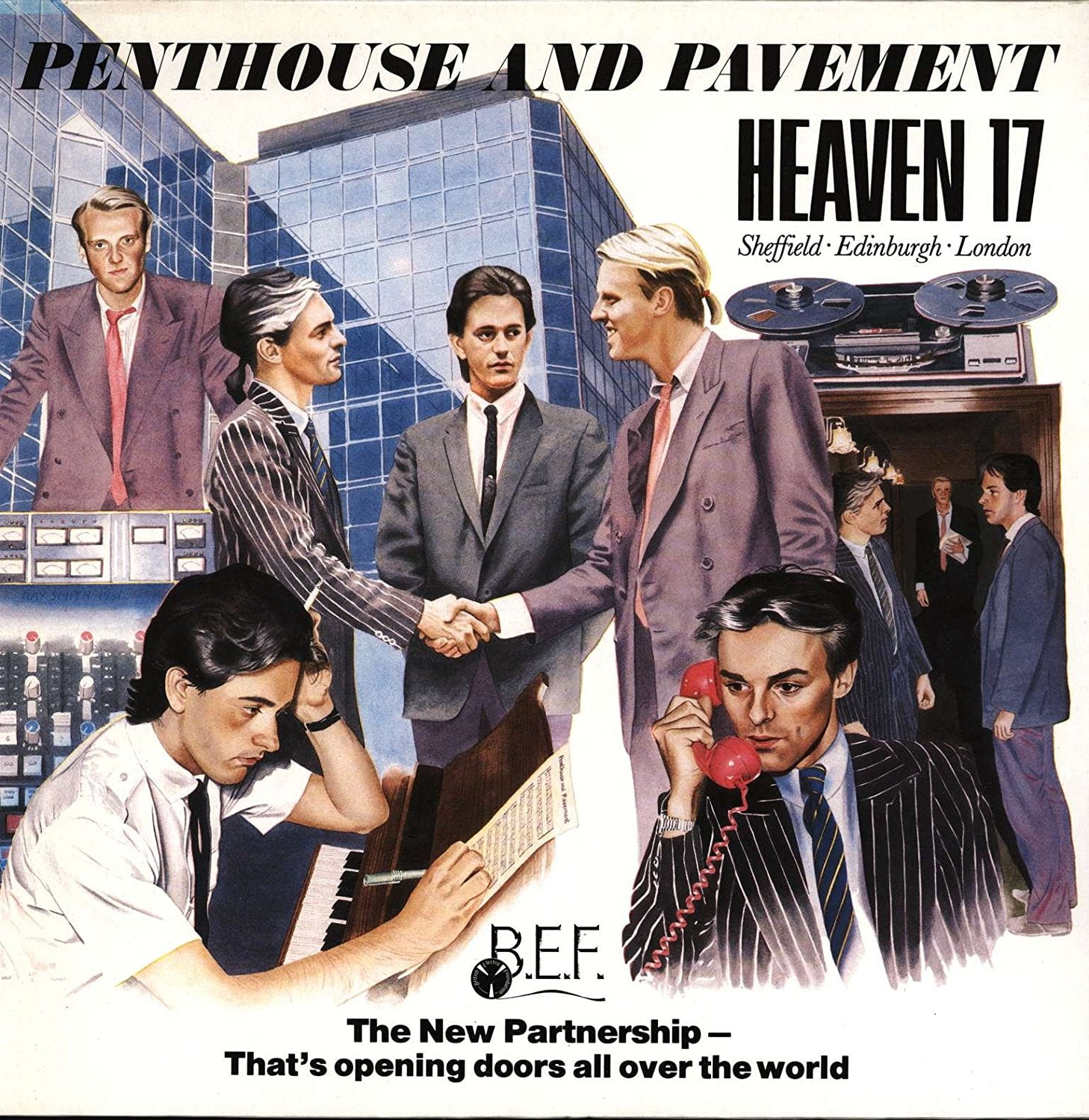

The trio highlighted the contrast in material by dividing their debut album into two: the ‘pavement’ side of the album represented their primitive, electronic side while ‘penthouse’ was where they featured a more vibrant, experimental sound.

Aside from the sonic reference, Penthouse And Pavement represented their own journey. “The duality of the penthouse and the pavement was the aspiration of what the working class could do if they set their minds to it, but grounded in a grim reality as we saw it,” Martyn says. “The pavement side was us waving goodbye to our pure, electronic pop – that’s where we came from. The penthouse stuff was really an indication of where we were heading musically.”

The public’s first taste of Heaven 17 came with the release of debut single (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang in March 1981. Received positively by the music press, it looked like Heaven 17 would score a huge hit and get their big breakthrough. However, a ban slapped on the song by Radio 1 for its controversial lyrics proved disastrous and the single stalled outside the Top 40.

Two months later the group released Play To Win, again the single failed to crack the Top 40 despite radio airplay and a performance on Top Of The Pops. This proved even more disappointing for Martyn and Ian, as it coincided with The Human League’s first Top 20 success with The Sound Of The Crowd.

Undeterred, the trio released their debut album in September 1981. Critics praised their bravery in tackling global issues and their innovative take on synth-pop by incorporating futuristic funk into the mix. Despite not having produced a genuine hit single, the album reached No.14 in the UK and spent a total of 77 weeks in the chart, making BEF’s first pop project a success.

The album’s iconic artwork by Ray Smith helped define their aesthetic. The depiction of the band as businessmen wearing sleek suits surrounded by the latest state-of-the-art technology was an ironic take on the emerging yuppie culture and capitalist greed.

However, the message was lost on the movement it was mocking and songs such as Let’s All Make A Bomb became adopted anthems by oblivious fat cats and city traders.

“Ian came up with the title of Penthouse And Pavement and we loved it. He also brought in a Newsweek magazine or something like that,” Glenn told Penny Black Music. “There was an ad in it for something like Toshiba. It was a really dull ad for big business and Ian said we should make something like that the front cover. From there we came up with the logos which appear on the sleeve of ‘The New Partnership – That’s opening doors all over the world’ and ‘Sheffield-Edinburgh-London’. The latter came from a packet of Dunhill cigarettes that was in the studio and had something like “London-Paris-Rome” on it. We stole all kinds of influences like that.”

The careful construction of that slick image was a deliberate attempt at presenting themselves as a brand rather than a band, pre-empting the direction of the music business in years to come.

Having taken their name from a fictional pop group of the future, Heaven 17’s forward- thinking and innovation in determining how a modern pop group should function has proved alarmingly prophetic now we are living in their future – with not only the group’s sound, but the political issues they highlighted as relevant as they ever were.

The Songs

1. (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang

Clocking in at almost 160 BPM, (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang owes more to the futuristic dance of Giorgio Moroder than the experimental electro of Kraftwerk. Completed within 10 days of forming, Heaven 17 took an instrumental track called Groove Thang, which they had initially written for the debut British Electric Foundation album Music For Stowaways, and developed it for their debut single. Adding a bass guitar rhythm track by John Wilson, the song was given a funky, new-wave feel. The single’s condemnation of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and President Ronald Reagan proved an ill-fated move. The song was banned by the BBC due to concerns by Radio 1’s legal department that it libelled the new US leader.

2. Penthouse And Pavement

Drawing an obvious influence from American R&B, the album’s title track is a funk-driven groove that prominently features female back-up singer Josie James on the chorus (a template which they would later perfect on their biggest hit, Temptation) and rhythm guitarist John Wilson. On the surface a party song, its lyrics tell a different story, alluding to being a slave of a greedy capitalist system – a theme they would further explore on 1983’s Crushed By The Wheels Of Industry.

3. Play To Win

Undeterred by the under-performance of (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang, Play To Win was released as a single. Once again using dance music to soften the blow of their political message, Play To Win landed them their first spot on Top Of The Pops. Despite the increased promotion, Play To Win only reached No.46 – one spot lower than …Fascist Groove Thang. In 2016, the song was introduced to a whole new generation when New York DJs The Martinez Brothers remixed it and made it one of Ibiza’s biggest tracks of the summer.

4. Soul Warfare

Continuing the theme of selling your soul, track four on the album continued to hammer home the group’s anti-capitalist stance. Presenting an overwhelming sense of spiritual desolation, Soul Warfare highlights capitalism’s game-playing and the strategy that is involved in acquiring control: “You could be part of me/ Forget the wealth you’re forsaking/ Your strategy is clear/ My soul is there for the taking.” It is this damning call that brings the ‘pavement’ aspect of the record to a close.

5. Geisha Boys And Temple Girls

Ushering in a different sound, Side Two begins the ‘penthouse’ sequence of songs. Contrasting sharply with the numbers on Side One, Geisha Boys And Temple Girls kicks off with a distinct synth solo which sounds like a cutting-edge take on a classical piece – very reminiscent of the soundtrack to A Clockwork Orange.

6. Let’s All Make A Bomb

Let’s All Make A Bomb is one of the album’s most misunderstood tracks, with many believing it to be about making money. Ware denies the lazy interpretation, explaining it to be: “About mutually assured destruction and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. You’d never put those in the lyrics but that was the philosophical basis we were working from.” Highlighting the ridiculous notion that governments would happily fund war and arms, rather than tackling global issues such as famine, disease or industry, Let’s All Make A Bomb is more relevant today than ever.

7. The Height Of The Fighting

Released as the final single from the album in 1982, The Height Of The Fighting failed to chart. Dealing with the subject of the Cold War arms race, the track serves as both a rallying plea for anti-capitalist insurgency while simultaneously satirising militarism. Musically, the song’s innovative use of synths and samples, proved influential for a whole generation of electronica artists.

8. Song With No Name

If there was ever any doubt as to how much of an input Martyn and Ian had into The Human League, the eerie Song With No Name dispels it. This curious number appears to tell the story of an artist struggling with debilitating writer’s block, before smacking the listener with its sinister, concluding twist.

9. We’re Going To Live For A Very Long Time

The album’s closer, We’re Going To Live For A Very Long Time is another deceptively cheerful track. With its sing-along chorus inviting everyone to join them, Heaven 17 use joyous terms such as “fun” and “party line”, but the offer is however prefaced with: “on the way to heaven”… giving the song a bleak inevitability.

The Players

As songwriter and producer on Penthouse And Pavement, Ware also provided backing vocals, played synthesisers, piano, percussion and programmed the Linn drum machine. During the 80s he worked for other artists, producing Tina Turner’s Private Dancer album and Sananda Maitreya’s Introducing The Hardline According To… before applying his production skills to Erasure’s I Say I Say I Say in the early-90s.

As a member of performance-art group Musical Vomit One, Marsh was a prominent figure on Sheffield’s punk scene in the late-70s. He swapped his guitar for a keyboard and founded The Human League, British Electric Foundation and Heaven 17 with Martyn. Ian left Heaven 17 in 2006 and no longer performs, choosing instead to teach music.

Gregory started out by performing with Ian Craig Marsh in a number of Sheffield-based bands, before leaving for London to pursue a career in photography. He returned to the city in 1981 to join Heaven 17 as the group’s lead singer. He has also worked with Martyn on BEF projects and established a career in soundtrack music, writing for radio, TV and film.

The Big Picture

Set in the headquarters of the BEF (British Electric Foundation), the video features the sharp-dressed men of the album cover brought to life. While seemingly on the verge of closing a big deal, their secretary (played by actress Emma Relph) conspires against them before she is uncovered. Penthouse And Pavement’s ambitious clip set the bar for Heaven 17’s increasingly cinematic future videos enhancing their polished image.

Play To Win

Having been designed as a new concept of pop group under the British Electric Foundation moniker, Heaven 17 originally set out to only be a studio-based band. With no plans to ever play live, believing tours to be “outdated”, Ware and Co favoured the new medium of music videos to promote their music.

As well as the challenges presented by recreating their tech-based sound in a live setting (they felt live instrumentation would change their sound too much), the two years Martyn and Ian had gigged with The Human League had proved financially disastrous. Concerts hadn’t translated into record sales and it was too much of a risk to take Heaven 17 on the road for fear of similar circumstances. Years later they would concede that touring would have cost less than their lavish videography.

Aside from TV performances on the likes of Top Of The Pops and The Tube, the group didn’t play a full live concert until the mid-90s.

However, when they did embrace the live arena, it kicked off a whole new era for the band and unexpectedly re-energised them. Beginning with spots on the Big Rewind 80s package tours and The Steel Town Tour (a joint venture with former foes the Human League and ABC), Heaven 17 proved to be an accomplished live draw. Unfulfilled by the short, hits-exclusive sets those tours limited them to, in 2010 they embarked on a headline tour to mark the 30th anniversary of Penthouse And Pavement. Playing the album live in its entirety, the tour was a resounding success – both for the band and their fanbase. It was so triumphant, in fact, that they decided to do it all again for the 35th anniversary in 2016.

Read more: Classic Album: Fever – Kylie Minogue

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.