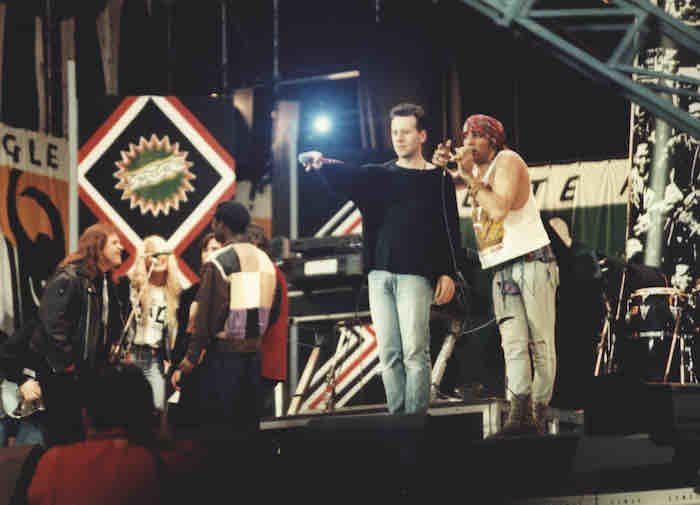

Staged to show solidarity with the world’s most famous political prisoner, while concurrently expressing opposition to an overtly racist system, the Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute Concert – held three years after Live Aid – was another example of music making a difference on a global level. Classic Pop revisits the landmark event… Written by David Burke.

On 11 June 1988, some 75,000 people packed into Wembley Stadium for the Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute concert. Broadcast to 67 countries and a worldwide audience of 600 million, the event was staged to mark the forthcoming milestone birthday of the imprisoned anti-apartheid revolutionary Nelson Mandela.

Both the Anti-Apartheid Movement and the African National Congress credited the event for raising global consciousness of Mandela’s incarceration, while others believed it hastened the demise of apartheid in South Africa. Its genesis can be traced back to The Special AKA song Nelson Mandela. Released in 1984,

the single was a UK Top 10 hit and written by Jerry Dammers.

“An old school friend remembered my antiapartheid activities and told me about a concert that was being staged at Alexandra Palace to commemorate the 65th birthday of someone called Nelson Mandela,” recalls the founding member of The Specials and 2 Tone Records mastermind.

“The concert was organised by Julian Bahula, an exiled South African musician, and the Anti-Apartheid Movement provided literature explaining who Mandela was. I was already working on an African/Latin-sounding tune, so I decided to put lyrics to it and pass the message on.”

A Call To Arms

It was Dali Tambo, the son of exiled African National Congress (ANC) President Oliver Tambo, who approached Dammers with the idea of establishing a collective of British artists opposed to apartheid.

“The aim was to raise awareness about apartheid, Mandela and raise funds for the Anti-Apartheid

Movement and the ANC,” explains Dammers. “We urged artists not to go to South Africa or to sell

records there.

“Over the next few years we invited artists to take part in a series of concerts staged by various promoters under the Artists Against Apartheid banner. These shows featured, among many others, The Smiths, The Pogues, Salif Keita, New Order, Smiley Culture, The Bhundu Boys, Ranking Miss P and The Communards. We also organised a regular club all-nighter, The 3 AAAs, featuring top DJs such as Soul II Soul’s Jazzie B, Coldcut and The Wild

Bunch, which featured Tricky and future members of Massive Attack.”

In 1986, Dammers organised Freedom Beat, a free gig on London’s Clapham Common, and invited the likes of Gil Scott-Heron, Hugh Masekela, Sir Coxsone Sound System, Sade, Maxi Priest, Peter Gabriel, Paul Weller and Sting to take part.

“This was the largest anti-apartheid demonstration there had ever been in the world at the time. Aerial photos show at least 200,000 people. It was a truly integrated crowd, black and white people together, and was helped a huge amount by DJ Tony Blackburn, who plugged the concert every day on his massively popular Radio London soul show.

“That was one of proudest achievements of my life. Performing Nelson Mandela with an all-star band, to a dancing crowd that stretched as far as I could see, was unbelievable. During Big Audio Dynamite’s set the police told us to turn off the power and we had to run around pretending to have lost the key to the cupboard with the generator in. It was completely absurd, but the officers seemed to be taken in – I think they were just following orders and secretly liked what was going on.”

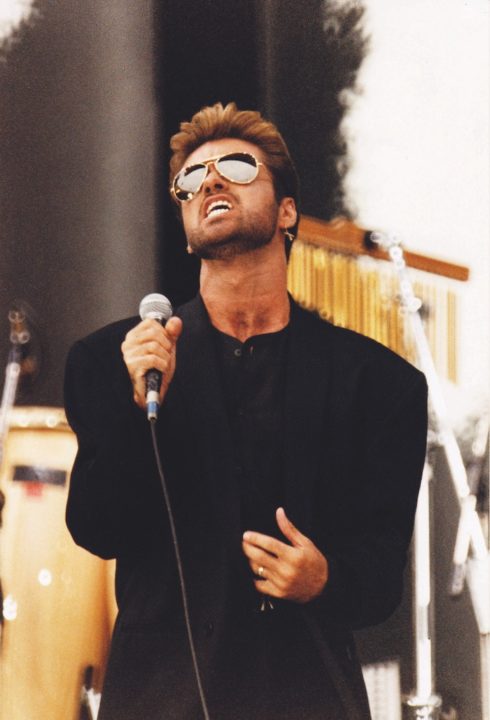

Photo by Peter Still/Redferns

If You Built It, They Will Come

Inspired by the response to Freedom Beat, Dammers wanted to go bigger – the objective, he asserted, was: “Always to try to take it as far as we could and reach as many people as possible.”

He told Classic Pop: “Although Clapham was a great success, the Anti-Apartheid Movement had lost a lot of their limited funds on staging a free concert, so it was necessary that the next big event should be ticketed. Wembley Stadium was suggested as a potential venue by a promoter called LMS and a date was pencilled in for August 1987.

“I contacted a handful of very big names. Dire Straits were the biggest rock band in the world at that time and they replied saying that they couldn’t do it that year, but would be interested the next. At the last minute, Simple Minds said they would like to do it, but by that time it was too late.”

Dammers was also talking to Tony Hollingsworth, who ran a small production company called Elephant House. He had been involved with the Glastonbury Festival and The Secret Policeman’s Ball, and possessed an impressive contacts book. His partner, Neville Bolt, knew the right people in television.

“I think Tony had done one concert for Artists Against Apartheid at the Royal Albert Hall, and had offered to make his services available,” says Jerry. “I decided to advise the Anti-Apartheid Movement to employ Elephant House to produce a show at Wembley.”

The Revolution Will Be Televised

According to Hollingsworth, in the 2014 documentary One Humanity, it was he who got a commitment from Dire Straits, the proviso being they wanted an act of similar stature who could sell out Wembley. Dammers had just the act. Simple Minds were not only one of the biggest bands on the planet, they were also members of human rights organisation Amnesty International. Frontman Jim Kerr had, from an early age, been acutely aware of the “unfairness and humiliation” of apartheid.

“We knew there was something in the air,” says Kerr. “As we understood it, apartheid was collapsing anyway, but it needed a few more pushes. The British government was dragging its feet. Now I’m older I understand that big business corporations had so much influence.

“But there was no getting away from the very basic premise that apartheid was outrageous.”

For Kerr and the rest of Simple Minds, refusing Dammers’ request wasn’t an option. “He came up to Edinburgh, where our manager’s office was, and we didn’t hesitate when he asked us to play. The integrity flows out of Jerry Dammers and he had brought the people from the Anti-Apartheid Movement with him – people like Archbishop Trevor Huddleston [the British Anglican who spent years fighting apartheid in South Africa]. There were establishment figures ready to go, they just needed the rock’n’roll, really.”

With two heavy-hitters confirmed, and the backing of the Anti-Apartheid Movement and the ANC, the business of compiling the rest of the bill began in earnest.

“Once the show was up and running, Tony Hollingsworth made it clear that he wanted to choose a lot of the artists” says Dammers. “That did come as a surprise to everyone, but for the sake of the event I stepped back and I think Tony did a very good job overall. I was quite tired anyway, having worked unpaid for three years, and I knew the stress of putting the Clapham Common bill together.

“I think most of the invitations that went out to artists were actually signed by me and I remember asking Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics by phone. I did put a lot of pressure on Tony to secure a major black artist.

“He said he had BB King, whose music I love, but I said it needed to be a huge current artist… someone of stature who would balance Dire Straits. It was not until the big US artists, like Whitney Houston, came on board and agreed to perform, that I started to really relax.

(Photo by Peter Still/Redferns)

“Whitney got terrible press on the day, which I didn’t understand. She was a prima donna, but for such a hugely popular American artist to agree to take part was a very brave move for her. The show wouldn’t have been so successful without her, so she deserved a lot more credit than she got. I also remember putting pressure on Tony to include reggae and hip-hop acts. I was pleased when were able to secure the talents of Sly and Robbie, Aswad, UB40, Salt-N-Pepa, Derek B and The Fat Boys.”

Several weeks before the tribute, Hollingsworth, who had been snubbed by Sting’s manager, Miles Copeland, flew to Switzerland where The Police’s former singer had been performing. Hollingsworth rang reception from his room and asked to be put through to Gordon Sumner [Sting]. “I introduced myself and told him that his management had stopped me from talking to him,” he said. “He told me his room number and he greeted me in his shirt and underpants. I told him why this was important and why he should appear. Like all the artists, he had questions…” Satisfied with Hollingsworth’s answers, Sting agreed to get involved.

“With the roster now comprising a diversity of major artists from differing genres, we knew we had something that was attractive to broadcasters,” revealed Hollingsworth. “We also had the musical content that could help us to communicate with the audience and persuade them to give to the cause.”

Hollingsworth took his proposal to the BBC which, with its World Service operation broadcasting to 180 countries in 50 different languages, offered the broadest platform. The Beeb were initially apprehensive, but eventually agreed to televise the whole event.

Image: Dean Chalkley

A Meeting Of Minds

When Simple Minds eventually met Nelson Mandela several years after they’d performed at his 70th birthday concert tribute, all he wanted to talk about was fishing…

“We met him a couple of times, and he was great,” said Jim Kerr. “The first time was when he came and gave a thank you speech to a roomful of artists and we were all there. Not only did Mandela thank everyone profusely, but he said: ‘When there was no voice allowed, we could always feel and hear the voice of the artists…

“That was the oxygen we needed’. That is potent and I’ll never forget it.

“It was so great to hear him validate what we had done. When you, as an artist, get involved in such lofty things there’s always critics and your own inner voice that is questioning: ‘Who am I? Does this work? Are we pissing in the wind? How far does it go?’

“When Charlie [Burchill] and I got to speak to him all he wanted to talk about was Scotland. He was a fisherman and wanted to know about salmon and all that – of which we knew fuck all! We’re from a housing estate and I’d never seen a fucking salmon in my life! He was a fan of boxing and we talked about that, too. He had a glint in his eye. He is a man of great stature and a wily old fox as well… you wouldn’t have messed with him.”

Photo by Peter Still/Redferns

An Anti-Apartheid Anthem

Simple Minds penned the anthemic Mandela Day for the occasion, believing that other artists were doing the same.

“One of the things that attracted us to it, artistically, was an early conversation that suggested everyone appearing would write a special song,” says Kerr.

“I thought that was a great thing, because then you don’t get everyone turning up for the party and not really saying their piece. I thought that was interesting. So, we set about writing ours… I don’t know what happened to the rest!

“The title, Mandela Day, worked well. We were already writing tunes for an album and I remember Charlie Burchill and Michael MacNeil playing this cascading melody that had a feeling of both sadness and hope. I made the connection that this was the sort of ambience we wanted. It wrote itself very fast. It’s not complex musically, which I think is important for something like that. It had the right emotion.”

Although the concert was held ostensibly to celebrate Mandela’s 70th birthday, the fact that he was still imprisoned on Robben Island, and that apartheid was still the rule of law in South Africa, meant there was little rejoicing.

“When you think about it now, it’s actually amazing that the BBC got behind it,” says Kerr. “Something like Live Aid was a charity concert, but this was very much a political concert. “We were all young and idealistic. There was the concert a couple of years later when he came back to London – that was celebratory. But there was anger and frustration [at the first concert].”

Anger Is An Energy

That anger was articulated by Steven Van Zandt, guitarist with Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band and creator of the activist group Artists United Against Apartheid. Before launching into an excoriating Sun City, he declared: “We the people will no longer tolerate the terrorism of the government of South Africa… we will no longer do business with those who do business with the terrorist government of South Africa.”

Actress Whoopi Goldberg, a presenter on the day, alleged that she had been told not to say anything political – a warning that had come from a producer at the US television network Fox.

Only six hours was aired in the US and a number of artists had their songs or speeches cut. When Van Zandt watched the broadcast later, he described it as “a totally Orwellian experience.”

In more backstage drama, the hard disc of Stevie Wonder’s Synclavier keyboard, which held 25 minutes of music, went missing. The soul legend was inconsolable, and left the venue with his entourage. Tracy Chapman, who had already played, filled the gap by playing Fast Car and Across The Lines. The performance

would catapult her to stardom. Before the concert, she had sold about 250,000 albums, two weeks later, she was said to have sold two million.

Wonder did return to Wembley and Hollingsworth persuaded the despondent singer to play, after Salt-N-Pepa’s performance. “There was no announcement, no sound or lights on the main stage and then, from out of the darkness, came the opening lines of I Just Called To Say I Love You,” Hollingsworth recalled. “There was a huge

audience scream, the most amazing thing I’ve ever heard, a great scream of happiness. Then the lights came on and Stevie plays the rest of his set.”

Lasting Legacy

So how influential was the concert in bringing about Mandela’s release and the downfall of apartheid?

Dammers says: “I have always said a political campaign is like a clock – the smallest cog is as important as the largest. A huge amount of people contributed to making things happen without ever expecting, or getting, any recognition.

“Taking over the TV stations was the first thing they did in the revolutions in Eastern Europe, so for the campaign to take over the BBC for a whole day, with a political message like that, was a kind of revolution. It became obvious that Mandela and the anti-apartheid message had become so popular that even politicians like Thatcher had to change their tune publicly.

“I hope the global broadcast helped consolidate support and keep the pressure on. Ultimately, it was the black people of South Africa who got rid of apartheid and many gave their lives… what we did was nothing compared with that.”

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.