Declaration of Strength: The Alarm interview

By Classic Pop | August 28, 2018

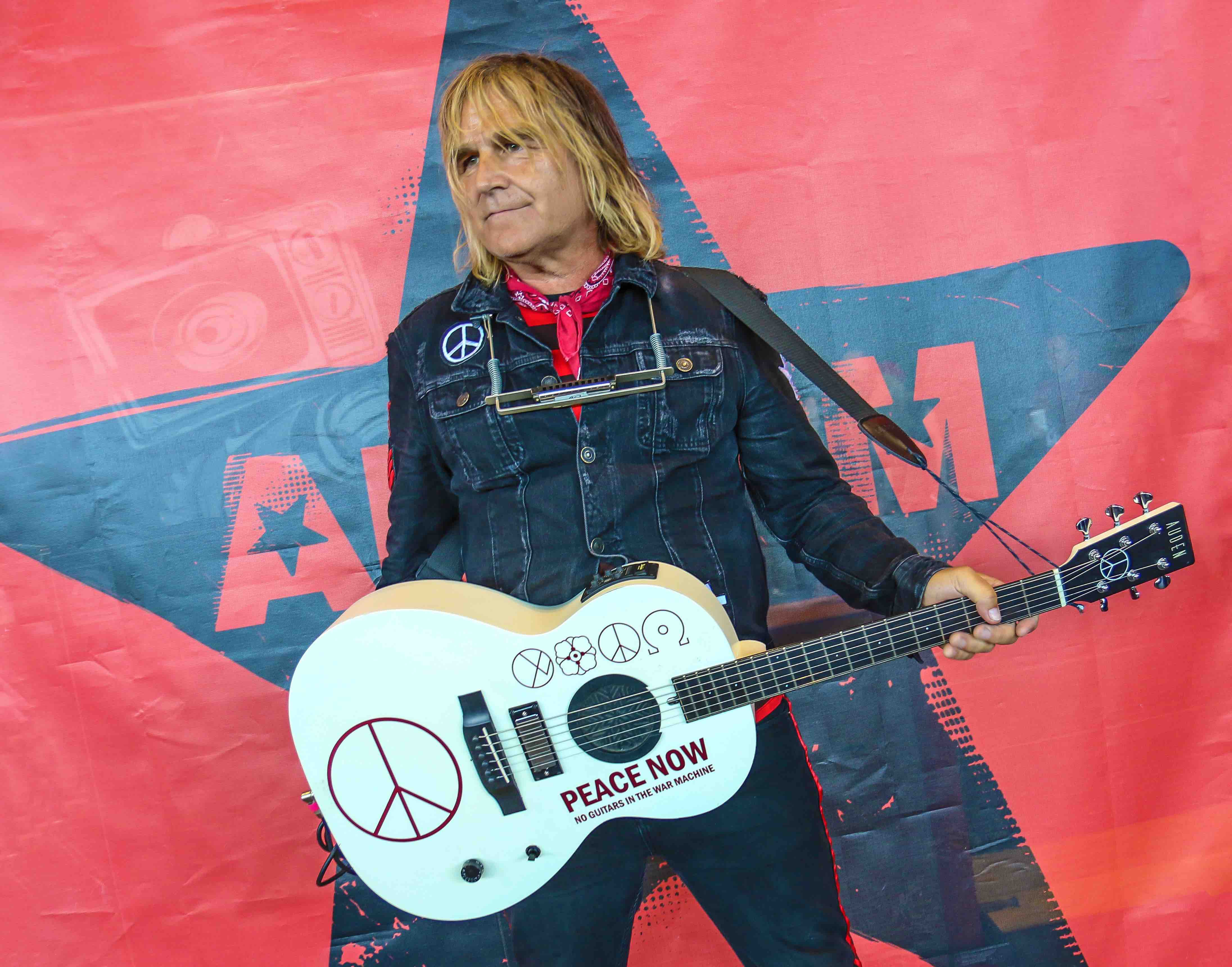

Heralded as ‘the new Clash’ when they first emerged from the pub circuit, The Alarm would go on to grace some of the world’s biggest stages. However, while Mike Peters might’ve survived the punk rock wars he reveals to Classic Pop how more significant battles lay ahead…

Manchester, May 1977. Eighteen-year-old Mike Peters has travelled from hometown Rhyl for the weekend and takes the opportunity to see the White Riot Tour’s stopover at the Electric Circus. Standing in the gents, just before headliners The Clash are due on stage, Peters is amazed to find himself sharing the urinal with the band’s entire line-up. The ever-curious Peters couldn’t let such an opportunity go to waste and asked Joe Strummer what White Riot was all about… “He told me it was about the future,” reveals Peters. It was Peters’ second interaction with punk royalty. The previous September he had seen the Sex Pistols in Chester and was told to eff off when he approached Johnny Rotten after the gig and asked him a similar question about Anarchy In The UK.

Those encounters triggered Peters to start a band and write his own lyrics… Rarely has spending a penny had such momentous consequences.

Before long, Peters was frontman of a punk outfit called The Toilets. Peters and drummer Nigel Twist (born Buckle) continued to work together as Seventeen, picking up bassist Eddie Macdonald and guitarist Dave Sharp (Kitchingman to his mum). Peters and Macdonald – neighbours since the age of five – formed the songwriting axis of the group. Although Macdonald was useful in terms of riffs and chord sequences, Peters notes: “I was the one that could put it into a complete song structure and finish it all off before adding all the lyrics. I’d also write my own songs alongside that. But then Dave wrote some amazing songs all on his own. Dave had been in the Merchant Navy before he joined our band and he had a worldliness and a confidence that I didn’t have.”

Set The Alarm Bells Ringing

The group, who relocated to London in 1981, renamed themselves The Alarm, but the most momentous alteration was to their sound. “I always felt that when we played our songs on electric guitars, something was missing,” explains Peters.

The day Sharp added some pick-ups to Peters’ acoustic guitar engendered a lightbulb moment as they began, “playing acoustic guitars, but very loud.”

Peters reflects: “It changed the way we tonally approached our music and the band.”

It also constituted a gimmick that got them attention from both audiences and record companies, something assisted by the 1981 release of their self-pressed single Unsafe Building. Signing to the independent I.R.S. Records label seemed like a good idea – because it was run by Miles Copeland, who had guided The Police to superstardom.

Clash Of The Titans

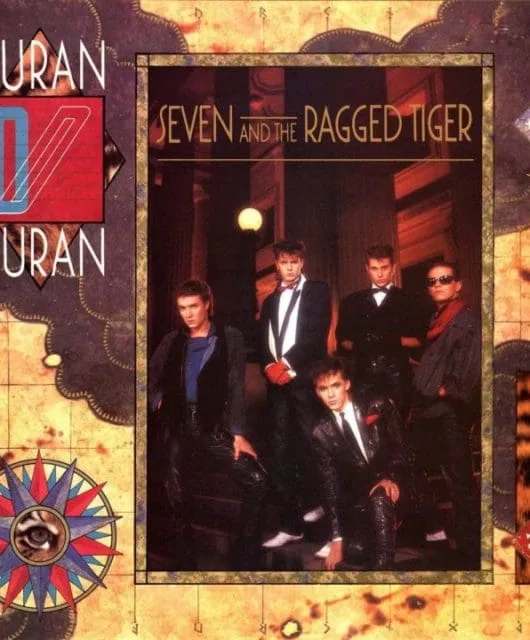

Declaration, released by I.R.S. on 14 February 1984, was The Alarm’s celebrated long-playing entrée. In a comment that will shock some, Peters says: “I felt Declaration was a bit of a disappointment. We’d created five tracks that were released in the US as our first EP. In the States, that was viewed as our debut album. I always felt that there was an album between that and Declaration that sort of got away.” Peters’ issue with Declaration is the slick production conferred by Alan Shacklock: “When we came out of the studio with Declaration, we’d become a different band.”

Yet its transatlantic success demonstrated that many considered Declaration just fine. Those detractors of the record were less concerned by overly clean production than what might be termed epic emptiness. Although anthems like Sixty Eight Guns and Blaze Of Glory were as big and dramatic as the band’s hair, close inspection of their lyrics revealed, it was averred, that The Alarm had broadly copied The Clash’s rebel-rock template but surgically removed from it any genuine social relevance.

Peters points out: “We discretely did things like supporting the miners’ strike funds.” However, he also says: “I didn’t want our music to become like The Redskins or Billy Bragg, where you’re really just a mouthpiece. Our politics were about the politics of the individual waking up to who they were and then making their own choices. My role as an artist was to stimulate conversation.”

Certainly, plenty of erstwhile Clash fans had no problem with The Alarm’s approach. Peters says his group “definitely” stepped into the space The Clash’s 1983 rupture vacated. The Alarm and The Clash, in fact, had seemed to have intertwined existences ever since the piss-trough encounter. The Toilets played support to The Clash in Liverpool in 1977. The Clash and The Alarm ended up at the same agency. When Mick Jones was sacked by The Clash, the debut of his new group Big Audio Dynamite was as the support act at a Glasgow Alarm gig. Joe Strummer was somewhat less keen, memorably snarling that The Alarm were the wrapping on the chocolate bar that was The Clash. By 1985, Strummer’s animus led him to take his new-look Clash to busk outside a Leeds Alarm gig as a form of protest.

Come Back Stronger

For Peters, Strength (1985) wasn’t exactly ‘that difficult’ second album. He calls it: “The Alarm’s best album, song for song.” Highlights included Spirit Of ’76, a paean to the music that prompted him into a music career, and Walk Forever By My Side. The latter, a pledge of solidarity, was partly inspired by a tragedy that befell Gaz Top, a close band friend who became a television presenter. “Gaz found out his father had committed suicide while we were all in the studio,” recalls Peters. “It was the first time I ever saw somebody I knew really well, utterly broken.”

Strength built on the success of its predecessor. The accompanying tour saw The Alarm play to 26,000 fans at a UCLA gig shown live on satellite around the world and support Queen at Wembley Stadium. Something, though, was awry. “We’d played to all these millions of people and then we came home and had to ask our parents to stand us a few quid to go out for a night out.”

The I.R.S. deal no longer looked such a good idea. Bewilderment and anger fed into internal fractiousness as the group contemplated their third album. “In this battleground that had erupted around the band, I decided to go on holiday in Wales,” says Peters. “I thought, ‘I’ve spent the last four or five years telling everybody The Alarm come from Wales and I don’t know that much about it’. I wrote songs wherever I was. It was just after the miners’ strike and it was a terrible time for Wales in the fallout from all that. It put family against family, community against community.

When he returned with his heartfelt song cache, he was confronted with the issue of Sharp and Twist insisting that the Peters/Macdonald axis should cease its dominance of songwriting. “The only way we could resolve it was that we’d allow our A&R man, who we all trusted, to choose the songs that should go on the next album. He chose all the songs that Eddie and I had written and one of Dave’s, One Step Closer To Home.” Ironically, Peters says the latter hymn to perseverance is his favourite Alarm song of all time: “It brought me to tears. I thought he’d really raised the bar.”

The resultant 1987 album Eye Of The Hurricane had a slick and polished sound ideal for the prevailing norms on US radio, but the band failed to make the breakthrough effected that year by peers like INXS, U2 and Simple Minds. Two years later came Change, an LP which closed with A New South Wales and had a Welsh-language iteration. It was almost as if the band were dropping their gaze to something less grandiose than conquering the States. “We reverted into each other and tried to make an organic record,” says Peters.

With the album’s singles, bad luck was compounded by bad judgment. The bluesy Sold Me Down The River had to be pulled off the radio: “When we put that record out, the Marchioness riverboat disaster had happened and a lot of people had lost their lives.”

Follow-up A New South Wales wasn’t just rather parochial, but “wasn’t the right record for the US – rock radio wasn’t going to play a song built around a piano and a male voice choir.”

The Alarm decided on a new direction for a new decade. Peters explains the rationale for 1991’s Raw as: “Making it live in the studio. A sound that’s really in your face and not afraid of distortion and volume. We knew that everything was changing. We couldn’t just be safe.

Yet the bold new mission was undermined from the get-go by the album’s contents not being decided on merit: “Nigel and Dave wanted to make it an equal split of songwriting.” Peters thinks the LP commendable for what it is but notes: “It is like a ‘White Album’. That kind of record where it’s individuals working solo under the guise of a band. Nigel and Dave had both married American girls. Rehearsals were studies in getting people from all over the world to one room at the same time. It was so forced and it started to creep into everything we did and it comes across.” His weariness with the situation was manifested in his own writing. He half-admits that Moments In Time (originally called Swan Song) was his disguised way of telling the world that the band was finished. The Alarm’s plans to embark on a long tour to promote Raw were curtailed by Sharp’s decision to make a solo record. “He had one foot in and one foot out,” Peters says. “A gig was hastily arranged to bring the tour to an end at Brixton Academy. We were going to have a meeting the next day and put the band on hold, but Dave said he couldn’t come to it.”

Peters found himself in a Ziggy Stardust scenario. “I went out on stage and said: ‘Look, this is my last moment in The Alarm’ and left the band on the stage. I didn’t even know it was coming myself ’til I said it. We all thought Dave was going to be the one to leave.”

Last Man Standing

Peters had no choice but to embark on his own solo career. It was a humbling experience. “I realised at that point nobody knew who I was,” he recalls. “It was really tough, but liberating.” He also worked with Billy Duffy in Coloursound. “It sounded like The Alarm meets The Cult. It was exciting.” Unfortunately, it was scuppered by The Cult’s reunion.

Peters reconnected with Macdonald when the latter turned up at some of his gigs. The two collaborated on a Peters soundtrack for a play called Flesh & Blood.

“We got on well and Eddie said: ‘Let’s put The Alarm back together’.” The 1999 attempt to relight The Alarm flame got off to a bad start when Sharp said he wanted to concentrate on his next solo outing and Twist said he didn’t want to return without Sharp. Both, however, gave their blessing to Peters and Macdonald. However, it didn’t last. “Eddie did eight dates with us and then he decided he’d had enough. He didn’t like being back out on the road and wanted to focus on his life as a photographer.”

Peters is aware that his subsequent work under The Alarm banner is considered fraudulent by some fans. Ditto for his recent quasi-OCD re-recording of old Alarm albums. “When I was making my solo records, they were really continuations of ideas that had begun in the previous decade,” Peters points out. “All it didn’t have was maybe a Dave Sharp song alongside it.”

Equal Rights

The new Alarm spectacularly exploded on to the public consciousness in 2004 when they smuggled on to radio airwaves their snarly Top 30 single 45 R.P.M. by pretending to be a new band called The Poppy Fields.

“It was as big a moment for The Alarm as Sixty Eight Guns was.” says Peters. “We were all set to go. Then a year later, when we were about to follow it up, I got diagnosed with leukaemia for a second time and that put everything on hold.”

The health traumas in his life – as well as his own cancer diagnoses, wife and bandmate Jules was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016 – naturally suffuse the songs he wrote for new album Equals. “A lot of the time I was sat in a hospital room, with Jules having an ultrasound and me waiting to go and see my doctor. I saw them as being blood red songs, internal from the heart.”

However, other issues are addressed: “I could see the world changing around me: Donald Trump, Brexit, all this uncertainty, and I started to write another set of songs that were external looking

Perhaps one day Peters will write a song about how his career has been so peculiarly entangled with that of his one-time idols. Peters says his skin was too thick to be hurt by Strummer’s chocolate-wrapper putdown, but his pleasure is obvious when he tells of a conversation related to him by an Alarm fan who ran into the former Clash frontman in 2002. The fan sheepishly told Strummer that his favourite ensemble was The Alarm. Joe had said he would dish it out to that band because they were stood on his ground and that “everyone was calling them the new Clash”. However, looking carefully around, Strummer also revealed that he would sometimes find himself enthusing to Clash aide Kosmo Vinyl about intoxicatingly anthemic fare playing on the radio. Peters said: “Kosmo Vinyl would say: ‘Joe, that’s The Alarm, you’re not supposed to like them!’ So he admitted to being a closet Alarm fan all along. That made me feel better about it all in the end.”

Equals by The Alarm is out now. Click here for more details.

Read more: All Grown Up: Tiffany interview