They broke the Top 10 on both sides of the Atlantic with the sophisti-pop smash hit Breakout in 1986. Now, as Classic Pop finds out, Swing Out Sister are back with a new album and it’s all down to their fans… Written by David Burke.

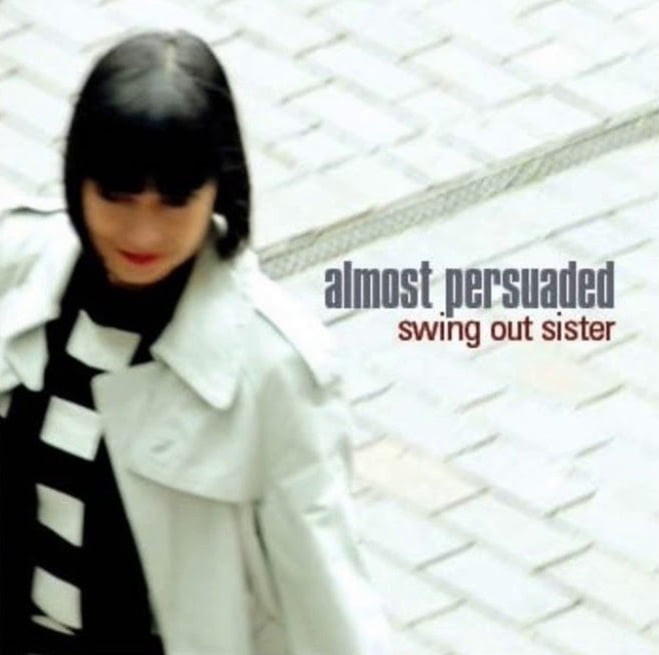

It’s been a long time coming, but Swing Out Sister are back with a new album, Almost Persuaded. However, as Corinne Drewery explains, it’s a record that they would never have finished if she hadn’t accidentally broken her femur in five places following a fall.

Drawing on a diverse range of influences from hip-hop and neo-soul to Blue Note Records and Motown, as well as allusions to Blaxploitation movies and half-remembered French film soundtracks, it materialised via PledgeMusic, which saw every step of the process shared with fans online through regular updates and short films.

“The Pledge campaign helped us to tighten up a bit,” admits Drewery – although it was Andy Connell, Corinne’s other half in both SOS and in life, who decided on the internet platform for the release.

“I was off the radar, in Lincolnshire visiting my family,” she says. “Andy said: ‘Oh, I’ve put it on PledgeMusic. We’re doing an album, we don’t know what it is – it might be an album, it might be a film, who knows?’ And people started signing up for it, so we thought, we’d better get our skates on then.

“It helped to have this rapport with our listeners. Andy kept putting down instrumental things with a view to hurrying me along, but the more he recorded, the more it made me freeze.

“I think it’s different when you lay down the meanderings of an instrumental than it is a half-finished song. A half-finished instrumental could be something like incidental film score music, but a half-finished song is a half-finished song. You need to get it in more shape before exposing it to the listener.

“That’s always been our relationship – Andy would just hand me an instrumental and then I’d give it some structure and finish it off. I kind of react to the music to try to make it into a finished song.”

There was regular feedback from Swing Out Sister devotees which was mostly encouraging and insightful. Drewery initially found this virtual intimacy with their audience somewhat daunting and “a bit intrusive” – not to mention the stigma associated with raising funds to subsidise the project.

“Andy and I were reticent about it at first,” she says. “It’s almost like you are going out with a begging bowl and asking people to pay for your record.

“Before, you would be very distant from your audience. But now, they can just send you a message and ask you questions direct. We’ve got to know them and there are some really interesting people.

“We have had a lot of feedback and it’s actually nice to hear people’s opinions. Sometimes it’s not always something you want to hear. But we are quite stubborn.

“We wouldn’t change something if it was something we felt strongly about. It’s almost like visiting a psychotherapist. You do all the talking and somebody is listening. It’s knowing that someone is listening, and knowing that you have to have something to report every now and then. It made us get our shit together.

“We started making films to show the work in progress. It became as much about making the films and showing the work in progress as it was about making the album. I think that slowed it down.”

But then came Drewery’s accident. “It was the day before we were mastering, and Andy said: ‘I think we’ve got a few more things we need to change’. I went down to London and planned to go to the mastering suite the next day. Then I fell over and ended up in hospital having an operation. I’m still walking with a stick, and I’m hoping people think it looks quite distinguished! It took me to fall over and break bones to finish this album – otherwise I think we’d still be recording now!”

According to Connell, the method of recording of Almost Persuaded was a nebulous idea to begin with.

“Things had changed,” he says. “The old rules didn’t work anymore. We used to get feedback from the record company. Without that influence we felt like we needed a slave driver on our backs.

“So, we decided we would offer that role to our fans and they could be fairly unforgiving!”

Going for Broke

Swing Out Sister will be forever known for Breakout, their second single, which made the Top 10 both in the UK and the US. That was back in 1986, and yet more than three decades later, it remains their signature song. Has the track become something of an albatross?

“It is an albatross in the sense that people want that from you,” says Connell. “I think it’s the time now for all things 80s. I get the feeling that there’s a climate of: ‘Yes, we’re welcoming that back again now, it’s been long enough’. There’s a strand of people who love the idea that we’re back, but would like us to be doing something exactly the same as we did then… which can be frustrating sometimes.

“We’re trying to get on radio playlists, and they’re like: ‘Well, it’s not what people are playing’. I remind them that they told us the same thing about Breakout. They said everything was synths and big hair, but along we came with our brassy thing and a girl with a bob. It was archetypally not what people were playing… until it was. A year later and everybody was playing it.”

They still love performing Breakout, changing the arrangement every time to keep it interesting. “I don’t think we’ve ever played it as it appears on the record. That’s the running joke. One day we’re going to surprise everyone by playing it like it was recorded!”

For Drewery, it evokes memories of a time when “a bunch of tykes from up north” were fêted from London to Los Angeles. “I think I felt like I was in some kind of strange dream,” she says. “It was everything I’d wished for, and more. I’d never been to the States before. When I went there for the first time, I spent all my time thinking I was Lucille Ball or Lauren Bacall, some Hollywood film star. It was very strange to be promoting your stuff in the US.

“It’s openly commercial over there, so I think I decided we were some kind of product like washing powder. You know those old 50s washing powder ads? I felt like I was in one of those strange adverts, so I decided to be Lucille Ball for our first tour of the States!

“Going to perform on Top Of The Pops for the first time, a programme we’d watched since you were a kid, and find yourself in that studio was kind of strange. It was a bit sad in a way to see behind the scenes, because it kind of blew the dream. It’s a small studio, you’re cooped up in the dressing room for hours. It’s not that glamorous. You run through the song a few times, you’re lucky if you get a good take after three or four run-throughs. You’re making it up as you go along. It’s weird that you’re going to be on television in front of millions.”

Follower of Fashion

Drewery, who spent her childhood in Nottingham and rural Lincolnshire, might have made it in the world of fashion had she not met Mancunian Connell and plumped for a career in music. She graduated from St Martin’s School of Art in London, where Sade was in the same year.

“We all went to the same clubs. We were attending some of the same classes. I didn’t know her that well, but I knew her as well as the other people on the course. Everyone was quite independent.

“We were all of a similar age, responding to similar influences. It was after the era of punk, then the New Romantic thing came. It was all about self-expression and our reaction to our parents’ generation. There was this whole jazz thing bubbling under at the beginning of the 80s. It was all getting a bit Blue Note and Verve [Records]. There was great imagery to go with that stuff. There was a bit of a romanticism about it. Then the warehouse parties started and dance rhythms came in. I believe when people think of the 80s, they think of synth-pop and fluffy hair.”

The Webb Effect

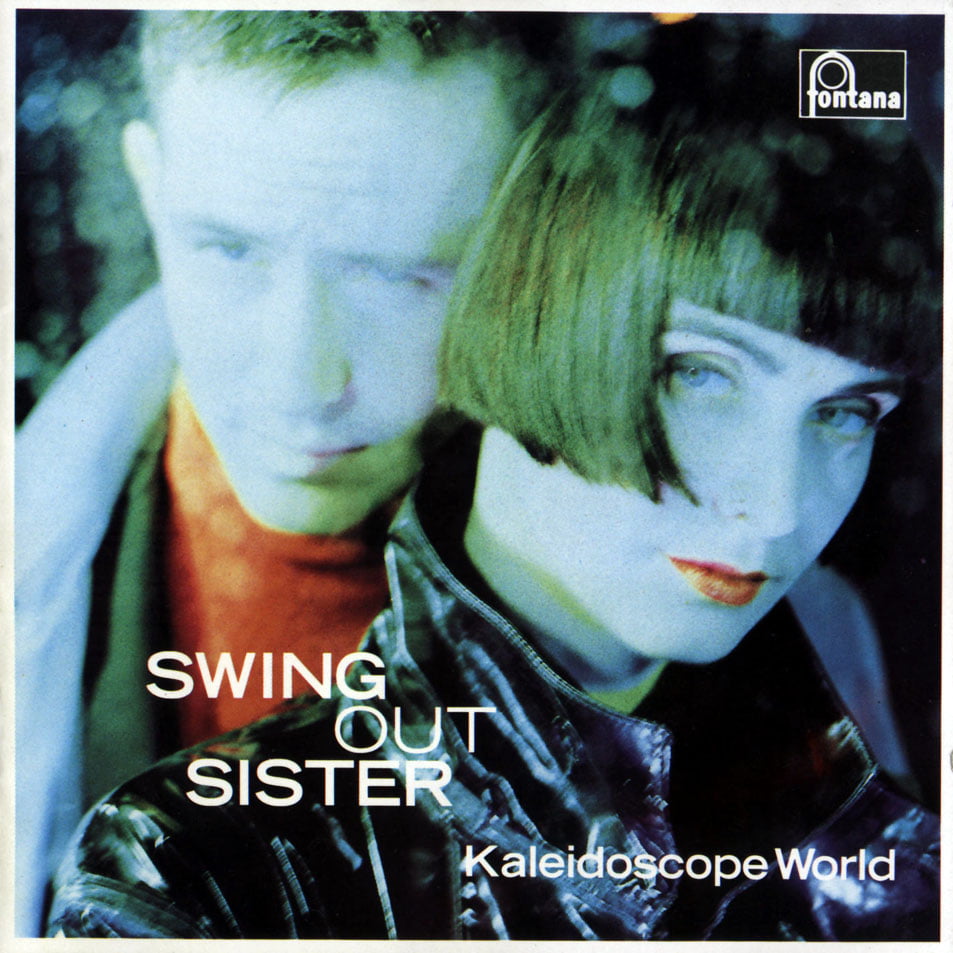

A transatlantic phone call led to an appearance by legendary composer Jimmy Webb on Swing Out Sister’s second album, Kaleidoscope World. Webb, famous for Up, Up And Away, By the Time I Get To Phoenix and Wichita Lineman, arranged the tracks Forever Blue and Precious Worlds for Connell and Drewery.

Andy recalls: “Paul Staveley was the producer, and it turned out that his brother was quite a celebrated engineer. He’d done a few Jimmy Webb records. Paul happened to mention us to them, and he said: ‘Give him a call, he’s a lovely bloke’. Somehow, we got his number and Paul called him in the middle of the night. He said: ‘Sure’. We sent him a couple of songs, and astonishingly to us, he thought they were good.”

SOS hired an orchestra for the session, and were snubbed by the musicians until Webb arrived. “There’s a certain dynamic that happens when an orchestra plays on a pop record. They have to let you know that this is beneath them, really. When we were doing that session, everyone ignored us. Then Jimmy came in and the room immediately changed, as soon as they recognised who it was. They just melted.

“Corinne made him a cup of tea. He didn’t know who she was. He was astonished that she’d made him a cup of tea. He was like: ‘Barbra Streisand doesn’t make me a cup of tea!’”

From a young age, she wanted “to sing and design clothes” – an embryonic creativity nurtured by her parents. Her mum was in a jazz band and dad played blues in his spare time.

“My mum painted pictures, and was always designing clothes, making them out of cushion covers and curtains,” she says. “I used to do it as well. I grew up in Nottingham, then we moved to the countryside and lived in the middle of nowhere. We were surrounded by fields and agriculture. So, you just have to make stuff out of what was there. It was like we were the Von Trapp family.

“I decided I had to do something that would involve training for a proper job. That was fashion. My idea of a real occupation was swanning down catwalks and flying off to different countries. While I was at college I was in a band. I liked music, but I liked the imagery of it as well. Obviously, I was a big fan of David Bowie.”

Classic Pep

Connell, meanwhile, was paying his dues as part of Manchester new wave funk pioneers A Certain Ratio, and later jazz pop outfit Kalima, who were signed to Factory Records. He had no inkling back then of the seminal scene evolving in the northern powerhouse. “When we started going to The Haçienda, I kind of presumed every city had a similar scene,” he recalls. “It was only later I found out that everyone was coming to Manchester.

“Certainly, in terms of Factory, you can’t underplay Tony Wilson’s part in all that. Those things need a catalyst – every movement needs somebody who can put it into words and thoughts. He was it and a total one-off. You were almost obliged to come up with something. It was expected of you to do something interesting. It’s like Pep Guardiola [manager of Manchester City, Connell’s favourite football team] – he makes a good player better.

“I think that Tony was the Guardiola of Manchester then! But he hated us – he hated the idea that we went to London, but we had to. As much as he professed to despise all that, he loved a bit of business – he loved a bit of entrepreneurial stuff.

“Having been on Factory and seen how it worked, I was very happy to be with a proper company who accounted more rigorously!”

Remaining Relevant

Drewery was singing with Working Week when she entered Connell’s orbit. “They drove up in the van to do a gig at The Haçienda. I was there with a mate of mine. She sang Venceremos, which she’d learnt in the van! Martin [Jackson, Swing Out Sister’s original drummer] and I had a kind of experimental electro thing that we decided might be good with a singer. It fell into place very nicely.

“In those days, it was a bit like a circus troupe. Anybody interesting could come along for a week and have a go. The main reason we kept Corinne was because she was working in fashion at the time, and she made polo necks, which I couldn’t find anywhere! She made us polo necks, so we had to keep her in the band for a few weeks!

“It’s very hard to find an English singer who sings in the English way – like Dusty Springfield. You know when somebody comes in and they’re from Bolton, then they start singing and they suddenly become a diva? It’s just the nature of the thing. Why would you sing in a Bolton accent anyway? But I think, because it had that English pop thing, it was an interesting thing to sit on top of what we were doing at the time. It made for an interesting combination, which was all we were really after.

“Anything that was an odd combination was good for us.”

An odd combination that has prevailed. A cursory listen to the smart, alluring soundscapes on Almost Persuaded, burnished by Drewery’s elegant, soulful vocal delivery, is affirmation, if needed, of why Swing Out Sister remain relevant. “If you ask certain people they’ll say we’ve evolved away from what made us successful!” laughs Connell. “The difference between now and then is, it was much harder to make a record in the early days – to make something sound like anything – and it’s easier now. We’ve wandered away from immediacy, in a sense, the idea that everything should be bright and bushy-tailed. There’s an adrenaline rush you get when you’re young and in a studio for the first time. Not knowing what you’re doing can be quite effective. In terms of our evolution, we’ve got better at knowing what it is we want to do. And maybe you lose something along the way in that. I think we’re much more satisfied with what we’re doing.

Melody Memory

“I was singing upstairs to my mum,” she remembers. “I think I was feigning illness. I was singing: ‘Why must I get up in the morning? I don’t want to go to school. I don’t love my mummy…’ I kept singing it through the tears.”

Andy Connell was tinkering around with a tune during one recording session, when Drewery was reminded of her extemporaneous childhood composition. “I started singing that over it. I said: ‘I’ve just had a weird recall in my mind. The first few notes are the exact same as a tune I sang when I didn’t want to go to school aged five’.

“But I think maybe all the songs we ever write are stored up inside us somewhere. Music is just there already, all around us. You’ve just got to pick out the bits you want. You’ve got to listen and find it.”

“We’re always surprised that we got the chance to do any of this, and that we’ve done it pretty well – an even bigger surprise, as far as we’re concerned.

“We pretty much felt we were bluffing most of the time. And then it turns out that everybody is. But you never lose that sense. Then you go back and listen and think: ‘That’s quite accomplished, actually’. We didn’t think so at the time.

“Wherever we’ve been along the line has been of interest to us. I don’t think we’ve ever sat and thought, ‘Let’s do something because it would appeal to somebody’.

“I remember Jimmy Webb telling us – which I thought was quite sad – he said he never played Up, Up And Away.

“He said it was the biggest song he had and he didn’t like the way it had come out.

“I loved Breakout from the start. If the biggest song you ever have is not one that you genuinely love, that must be a curse. So, we’re lucky in that regard.”

Almost Persuaded is out now. Visit swingoutsister.com for further information.

Read more: Here’s to Future Days: Tom Bailey interview

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.