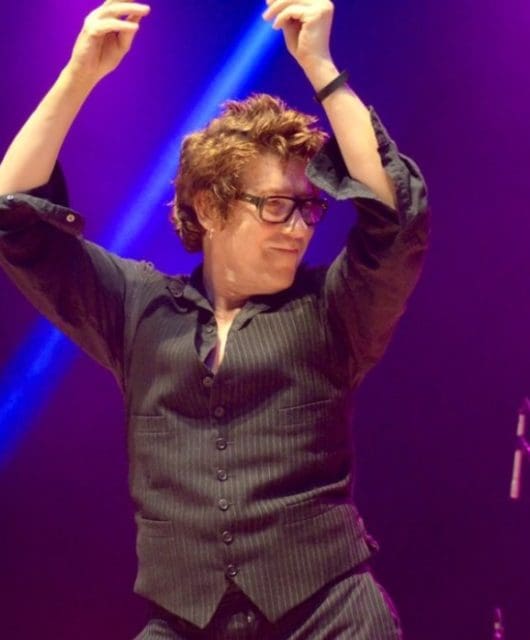

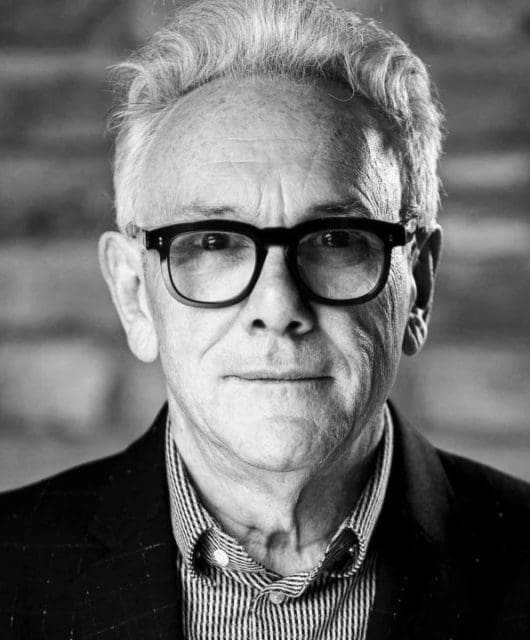

Reigning in Manchester: Paul Heaton interview

By Classic Pop | March 6, 2019

There’s pop royalty, and then there’s Paul Heaton. He might not have sold as many records as others but, as his first compilation showcasing everything from The Housemartins onwards demonstates, Heaton is the last King Of Pop. He sets out his rules for musical monarchy…

John Earls

On the train to Stockport to meet Paul Heaton, a text arrives. “Hiya. It’s Paul Eaton. Ouse Martins? Five Get Over Exciting? Your car will be waiting at the rear of the station, and your drivers are Barry and Linda.”

Now 56, Heaton only passed his driving test over the summer. Full of hugs and with a natural interest for anyone he meets that’s fed itself into his lyrics for decades, Heaton is excited to greet Classic Pop – “It’s the first time I’ve picked anyone up from the station!” – and admits he gets over his new-driver nerves by chatting constantly. During the short drive to his semi- detached home, Heaton confesses that his initial plan to treat driving as an opportunity to listen to more new music has already slipped away because, “I just listen to Radio 2, the same as anyone.”

Although Heaton’s house has been mentioned in profiles before, nothing can prepare you for its sensory overload. It’s magnificent. A black and white photo of local record shop Kingbee is in the hall, next to a framed display of football badges. The kitchen-diner where our interview takes place has football scarves around the walls, a test pressing of the most recent Paul Heaton & Jacqui Abbott album, Crooked Calypso, on the floor, plus the ephemera of Heaton’s two teenage daughters: a Doctor Who magazine cutting, Chewits, a Halloween pumpkin… Paul Heaton’s house is certainly full but in every respect, Paul Heaton has a very full life.

He’s only half-joking in calling his new compilation The Last King Of Pop. Collating 22 singles from The Housemartins, The Beautiful South and Heaton & Abbott, plus sparkling new song 7” Singles, its title is a pointer that this most principled of pop stars feels troubled by pretenders to the throne. “People have been let down so badly by figures in pop authority, I’m easily able to claim the crown,” Heaton attests. His home is one of the key reasons for his monarchy: “I live like a king should live.” Gesturing to his modest garden, he insists, “This should be monarchy: an ordinary person enjoying life.” Heaton’s family moved to Surrey when he was a teenager but otherwise, he’s never lived away from the north, saying, “A king should remain in his kingdom.” Morrissey is thus instantly disqualified. “A good pop singer and writer, but he’s gone out of the country. And when he comes back, he slags Britain off for being neighbourly. You couldn’t fucking write him, could you?”

Other regal-disqualifying traits? Tax evasion. Being too rock: “Not that dirty grebo shit Paul Weller comes out with. He’s supposed to be Mod, the dirty little bastard! I’m a pop singer.” Doing adverts: “I’m disappointed when songs that mean a lot to me by good lads like Elvis Costello and Buzzcocks are used in adverts. People have bought Rotterdam or I Gotta Praise on the condition it was made for them. I can’t then sell it to some dodgy bloke round the corner working for Toyota.”

What else? Well, trying too hard to look cool: “I keep a list in my diaries of people who chuck in fake news about themselves. They see T-shirts of Bob Marley and Jim Morrison do well and want those sales, but they don’t want to actually be dead. They go, ‘How can I make up a story that makes me look dangerous?’ and someone tells them ‘You could say you’ve taken

an overdose.’ That’s when you get that Dave Gahan bollocks – ‘Yes mate, of course you died.’”

A mention of Johnny Marr, whose studio is near Heaton’s house, does force him to concede some ground. “Yeah, Johnny’s very grounded,” he says. “But I qualify to be king by several measurements. Admittedly, they’re all my own measurements, but kings do that, too. I’m sure Classic Pop will get many angry emails claiming so-and-so is the last king of pop. But it’s my rules and I won’t fail to throw your readers into the sea if they ever question the king.”

Singer Turned Songwriter

It’s this freewheeling levity that has stopped critics – if not the public, time and again – from realising just what a golden talent Paul Heaton has been ever since The Housemartins’ Flag Day first played by John Peel in 1985. Despite his playfulness around its title, Heaton hopes the compilation will make people appreciate the quality of his songwriting. “I can’t take myself seriously for longer than a couple of minutes,” he smiles. “It’s a fault of mine, because I should be more serious, a bit. Lauren Laverne interviewed Paul Weller on 6 Music recently, and it was perfect, because he is able to talk seriously about his music. If it was me, it’d just break down into fart jokes.”

It’s not that Heaton isn’t able to analyse his songwriting in detail – he’s passionate about the importance of music in people’s lives. But he also grew up loving Spike Milligan and longtime Beano cartoonist Leo Baxendale, so absurdity is Heaton’s default setting. At the start of his career, he says he was a singer who wrote songs… now it’s the other way round.

“There was a specific vocal gymnastics early in my career, on songs like Let Love Speak Up Itself,” he assesses. “As I’ve aged, I feel less capable of expressing myself in that department. It’s one reason my lyrics have got better in the last 10 years, as I’m dealing with the darker side of my voice. I shouldn’t really be playing arenas anymore. I’ve maybe got another four years of that in me, but once I get to 60, can I still cut that? I don’t want to be a singer who people see and come away disappointed.”

Smaller Albums, Touring on a Bike

Such candour aside, Heaton is delighted that reuniting with former Beautiful South co-vocalist Jacqui Abbott

has led to three Top Five albums. The Last King Of Pop features seven of their songs, compared to just one – the celebratory Manchester – from the final three Beautiful South albums, and none from either of Heaton’s two solo albums. He admits he “withdrew into myself” in his solo career, making “smaller” albums because their impact had lessened.

“When I left The Beautiful South, I didn’t realise that my name doesn’t really mean anything,” he concedes. “People around me were saying ‘You’ve had all these hits, you’ve had 20 years at the top. How can they not play your new song?’ I was more philosophical about all that. And when I was in my shell, I did some good things.” He cites his musical The 8th and twice touring round Britain by bicycle, playing at pub venues – Heaton would love to formally establish the pubs which invited him to play as a nationwide circuit for up-and-coming musicians to learn their live craft.

Although Jacqui Abbott was part of the cast of The 8th, it was Heaton’s manager Simon Moran – also manager of The Stone Roses and The Courteeners – who persuaded Heaton to make records with his ex-colleague again. “I’ve never been into career growth,” he laughs. “I didn’t think The Housemartins’ second record had to be bigger than the first. When The Beautiful South were doing well, I wasn’t going, ‘Right, now we’ve got to make it in America!’ I was happy being an ordinary person on a wage. A great music wage, admittedly. Simon had a different outlook, pushing me to be less conservative. He said to get Jacqui back on board, get a proper producer, a proper studio.”

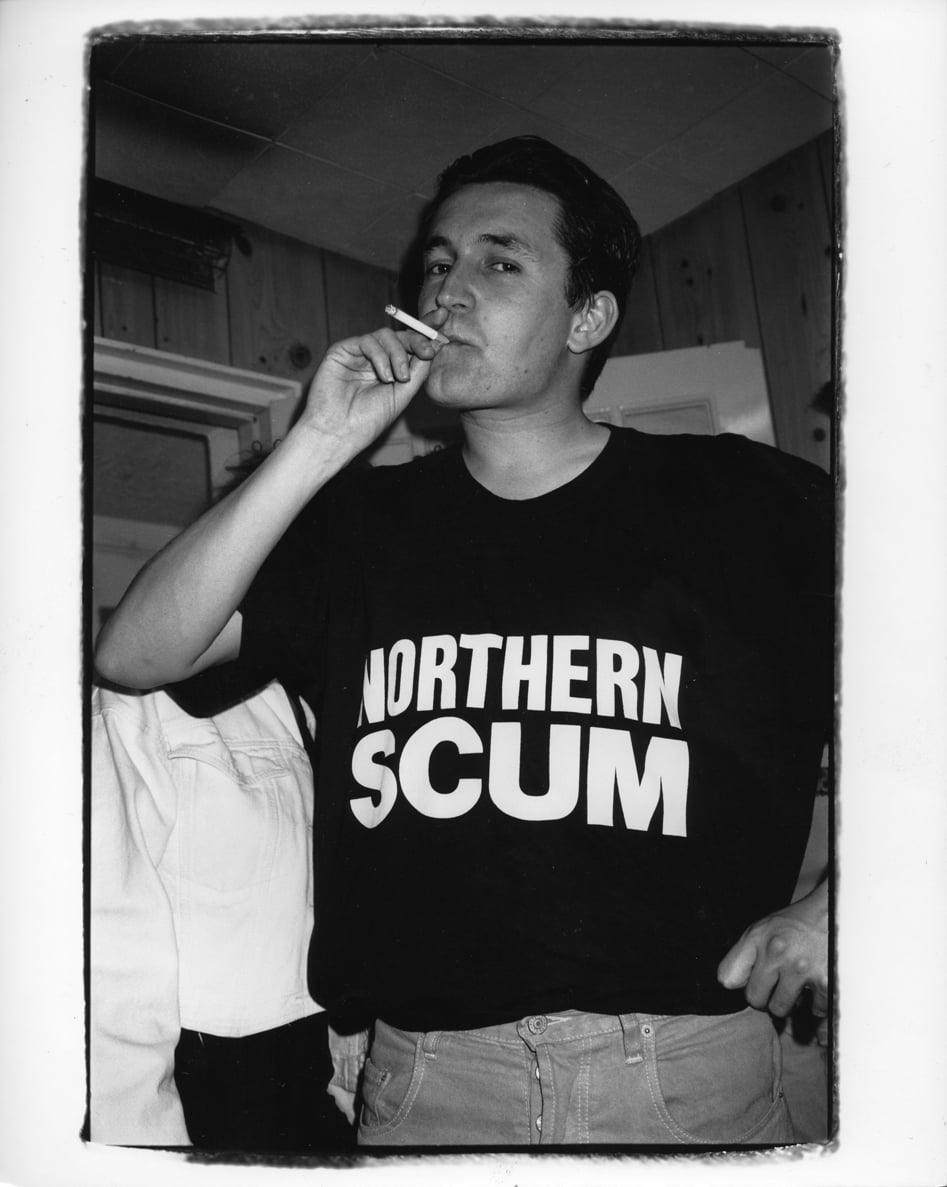

Having stayed busy in his commercial wilderness years, it also helps that Heaton has sorted his personal life out. He admits he drank and smoked too much in The Beautiful South, saying, “When I played arenas first time round, I thought, ‘This doesn’t feel like me.’ What’s happened with Jacqui, I think it’s been achieved and worked for a bit more.”

Heaton is married for the first time, too. Off work from her job as a teaching assistant on the day of our interview, Linda is as warm and friendly as her husband, laughing with and at him before leaving him to talk shop. “Being married is brilliant,” beams Heaton.

Linda has also helped Heaton come to terms with his drinking in a way the singer admits, “I’m incredibly lucky works for me.” He only drinks when he needs to write songs, the couple going on “drinking holidays” to Holland and Gran Canaria. “I’m not suggesting anyone else does it,” cautions Heaton. “I tried all the other systems: walking to the pub slower, only going to the pub on Monday. I tried going to the pub for three or four hours not drinking, and I couldn’t do it. What I do is practical for me. If I’m cycling past a boozer in the summer, I don’t think, ‘God, I need a drink!’ because instead I’ll think, ‘I’m going away with my wife in three months and I can drink then.’ It keeps drinking fresh, and I think it’s a system that will work for the rest of my songwriting career.” Two to six pints is Heaton’s window of opportunity for writing. “After that, lyrically I do as any drunk person does and start repeating myself.”

One of the few dark clouds in Heaton’s life is his relationship with the rest of The Beautiful South. Although their split in 2007 was amicable, it soured a year later when singers Dave Hemingway and Alison Wheeler and drummer Dave Stead formed The New Beautiful South, now called The South after “a pleasant meeting” with Stead to ask him to at least change the band’s name. Hemingway has since left.

“I’m fine with the others who aren’t in The South,” he shrugs. “The ones that are? It’d be nice to sit down and chat again, to have some level of friendship, even if it’s at a distance. But there is that thing between us they’ve done that’s clearly wrong. It’s sad, but they’re still alright kids, really. C***ish behaviour doesn’t make me think they’re c***s.”

Reunion? Probably Not

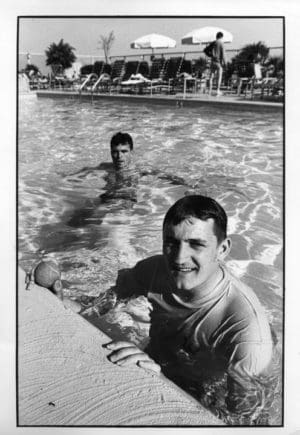

Conversely, the four members of The Housemartins are good mates 30 years after they split while still at the top, joking in their farewell statement that they, “weren’t good enough in a time of Rick Astley and Shakin’ Stevens.” Heaton, Norman Cook (who produced Beautiful South classic Perfect 10), guitarist Stan Cullimore and drummer Hugh Whitaker meet annually to reminisce. Cullimore, now a children’s author, “would be on that stage in 30 seconds” if a reunion was ever announced, although Heaton remains adamant that’ll never happen.

“The Housemartins’ music was sugary, sweet, indie and it was young. It would have looked sad any time after that decade to have reformed. It’s one of the advantages of being self-deprecating, that I see myself as Pudding Billy – this big, fat version of how I used to be. It’d be like people asking, ‘How come you don’t wear that cardigan anymore?’ I just gesture at myself and go, ‘Why the fuck do you think?’ Doing The Housemartins now just wouldn’t look right. I understand why Stan would do it. His approach is good and simple – it was good fun, so why not? That’s why we were a good band because it was Stan’s positivity mixed with my very occasional negativity.”

Heaton is first to admit he was lucky The Housemartins arrived when they did, at a time when, “Once you got played by John Peel, there was a 50% chance at Radio 1 that, unless your records were totally mad, then Janice Long might play you, too. And if she did, then Bruno Brookes probably would. There was a framework for getting success. There are probably just as many great young bands out there now as ever, they just don’t have the chances we did.” As king, he’s therefore forgiving of new acts that allow their songs on adverts.

Heaton is also pleased that his children don’t especially share his musical tastes – his eldest daughter is into drum ‘n’ bass and grime, his middle daughter prefers “really dark hip-hop”. Apart from his in-car Radio 2 addiction, Heaton only listens to new music. For decades, he’s kept monthly Top 20 charts of his favourite new songs in notebooks. He shows me his latest, a range of reggae, folk, hip-hop, R&B and pop as entertainingly freewheeling as the contents of his kitchen. At the end of our interview, he offers up a banana and an apple for the journey home. A passing Linda points out, “There’s all this fruit. You’ll notice none of it is in the fruit bowl.” She’s right – it’s too full of stuff. But that’s how a king should be: entertained by all of life’s diversions, living among his people. Paul Heaton deserves his crown.

Read more: Classic Album: Spirit Of Eden – Talk Talk