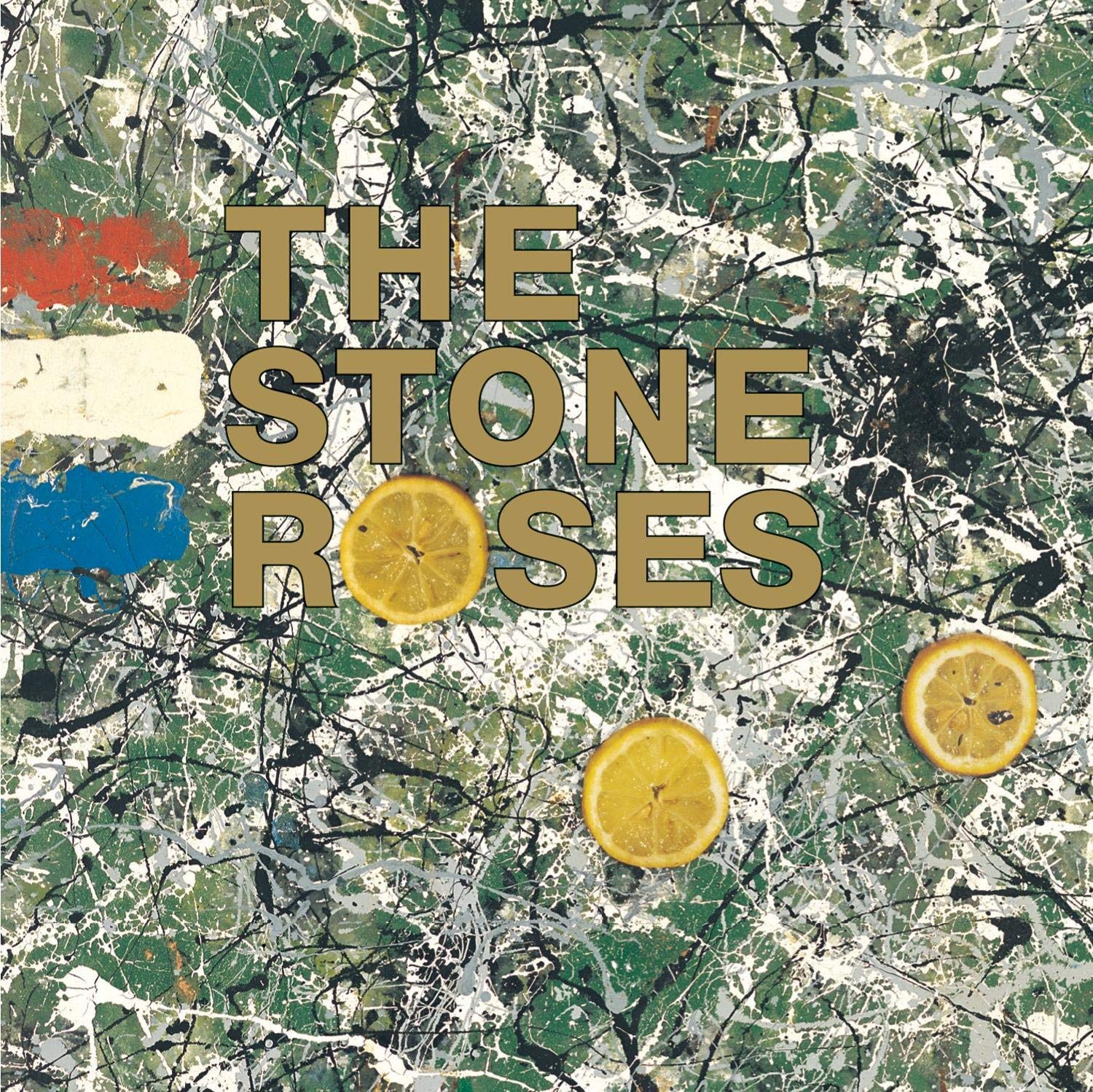

The Stone Roses rescued indie rock from shambling student bands and fired Manchester into a bright new musical future. Michael Leonard charts the making of a one-off album that, according to Noel Gallagher, “opened the door for British guitar music in the 90s”…

No. 1 in the NME’s vote on Best Albums Of The 80s. Top of their 2003 Greatest British Albums Ever poll. It wasn’t just the NME. It also won The Observer’s Greatest British Albums vote the following year. Runner-up in Channel 4’s Music Of The Millennium poll of greatest albums – that was a public vote.

The thing about The Stone Roses is, it’s an album that spans those sometimes overly worthy critics’ polls as well as being in tune with what real people think. Or, at least, people of a certain age…

There’s a heart-warming scene in Shane Meadows’ fan-centric documentary, Made Of Stone, released in 2013. In it, the four Stone Roses – John Squire, Ian Brown, Gary ‘Mani’ Mounfield and Alan ‘Reni’ Wren – have announced their reunion and decide to stage a free warm-up show at Warrington’s Parr Hall, capacity 1,100, and all you have to do to get a first-come first-served ticket is turn up at 4pm with a Roses record sleeve, T-shirt or a ticket to their later shows at Manchester’s Heaton Park.

Here they come, in low-key and orderly fashion; teens not even born in ’89, old men, mothers (with bemused toddlers in ‘I Wanna Be Adored’ T-shirts), time-cocooned bowlhead ‘ravers’, office workers, a bloke who’s lied to his boss that his father-in-law’s had a heart attack so he can leave work early…

The best one is a too-late, unsuccessful deputy headteacher: “I’ve just seen about three people I know going in… and they know nothing about music. I’m devastated.” Mr Teacher is still smiling, just about. “At least I’m here, I can say I was close to it,” he muses, standing outside.

That says more about The Stones Roses than any critics’ poll. It still causes respected middle-aged professionals to ‘lose their shit’. But why? “You know and I know, but you can’t write it down, can you?” another man says to camera in Made Of Stone. “This lot [gesturing to the queue behind] know. There’s a reason I’ve still got me hair like this 20 years later. There’s a reason I’ve never worn a tie. There’s a reason why I still listen to that album at least once a week…”

Let’s not over-analyse, then. You either understand, or you don’t. Here’s how Manchester’s Stone Roses made an album. Or to others: here’s how The Stone Roses made the greatest British album ever.

The Songs

The Songs

1 I Wanna Be Adored

A perfect, slow-building opener, Mani’s brooding bassline is slowly joined by the rest of the band to build the archetypal Stone Roses sound, falling somewhere between typical Madchester and shoegaze. Lyrically, …Adored is little more than a repeated mantra of rock-star mythology: “I don’t need to sell my soul/ He’s already in me.” In 2009, Brown told Clash Magazine: “I didn’t actually want people to adore me. I was trying to say then, if you want to be adored, it’s like a sin, like lust or gluttony or something like that.”

2 She Bangs The Drums

As a lyric of intent, “Kiss me where the sun don’t shine/ The past was yours but the future’s mine/ You’re all out of time” is some flag in the sand. Brown wrote these verses, while Squire wrote the chorus words that are ‘just’ a love song: be it to a partner, the music, the ecstasy of clubbing or whatever you want. What elevates it is the crystalline sonics. The rumbling undercarriage of Mani’s bass, Squire’s flabless guitars and Reni’s whip-cracking drums all rush with a faultless euphoria. The Roses hated being called ‘60s’, but this is very 60s, and a 101 on how to write a guitar-pop single. Released in July ’89, it was the band’s first Top 40 hit.

3 Waterfall

A fan favourite, swirling around a cascading Squire guitar arpeggio and with Reni providing notable shuffling drums and backing vox. Its melody is very folk-esque, and Brown has previously grumbled that John Leckie wanted to turn it into a “Byrds/Simon & Garfunkel thing”, which makes some sense: Squire listened often to The Byrds; Brown didn’t even own a Byrds record. Brown has said that it’s “about a girl who sees all the bullshit, drops a trip and goes to Dover. She’s tripping, she’s about to get on this boat and she feels free”… Squire also wrote parts of Waterfall’s lyrics.

The guitarist has never (as far as we know) fully explained, but ‘Madchester’-championing DJ/broadcaster DJ Pete Mitchell reckoned the words were at least partially about Squire’s loathing of the Americanisation of Britain (see “This American satellite’s won”). Proof? Squire’s own oil on canvas Waterfall (1988) meshes the Union Jack and Stars And Stripes flags. So maybe the lyric is about both. Whatever its origins, Brown has said that writing Waterfall in ’88 “was the first time we went ‘Wow, this is it!’”. Bonus points are also awarded for the excellent use of “brigantine sails” (a two-masted ship).

4 Don’t Stop

The music is, of course, the whole of Waterfall flipped backwards, on the basic Fostex 16-track recorder on which Squire/Brown recorded demos, with overdubs and vocals added later, and credited on the album as ‘Another Schroeder/Garage Flower Production’. The Roses had done this before, with Made Of Stone and its reversing for 12″ B-side Guernica. More nautical-themed lyrics abound, and the way Brown intones “Isn’t it funny how you shiiiiiine?” manages to invent Liam Gallagher at the drop of an anchor. Don’t Stop was also played live (with ‘forward’ instruments) and is still very strong in its own right, with Reni again outstanding on drums and backing vocals.

5 Bye Bye Badman

Positively bouncy compared to the shuffling swagger of much of the album, the band only began work on …Badman because they couldn’t complete a satisfactory recording of (future B-side) Where Angels Play, but finished this in just a few hours. Squire overdubbed his counter-lead guitar lines that run an alternative melody throughout in 30 minutes. It’s openly inspired by the riots in France of May 1968, as Ian Brown had met a Frenchman who’d been in the riots while the singer was hitching around Europe, and both Brown and Squire also admitted being “inspired” by a Channel 4 documentary on the 20th anniversary of the era, broadcast in spring 1988, called Revolution Revisited. For its lyrics, Bye Bye Badman could perhaps have been called I Am The Insurrection… if it didn’t sound so damn blissful.

6 Elizabeth My Dear

Side 2 begins with another nod to Simon & Garfunkel, in that the music is Scarborough Fair, a traditional English folk melody dating back to the 14th century, made most famous in pop by S&G’s soundtrack to The Graduate in 1968. The song is just 54 seconds, but gave Brown a springboard from which to vent. In various early interviews, he said: “I’d like to shoot Prince Charles” and added there would never be a revolution unless someone “put a bag over the Queen Mother’s head”. They won’t be getting OBEs, then.

7 (Song For My) Sugar Spun Sister

If there is a dip in The Stone Roses, it’s arguably here. There’s plenty of rock classicism in its chords and straightforward arrangement, sumptuous though it is, at various times recalling The Byrds, The Smiths, REM or Lennon and McCartney (basically, choose your own angle-pop reference point).

8 Made Of Stone

There are some distinct echoes of Primal Scream’s

9 Shoot You Down

A change in pace, with its low-slung swagger again highlighting Reni’s drumming prowess and more Hendrix-ian guitar from Squire. With its lyrics partly serving notice on all challengers, this is just the Roses coolly showing off.

10 This Is The One

The last song to be recorded for The Stone Roses, but one of the first written. This Is The One began life in 1985 when the band were locked in a room by producer Martin Hannett and told they weren’t allowed out until they wrote a song. They came up with this, lyrics by Brown, albeit in an uncultured and punkier form. It’s famously played at Old Trafford as Manchester Utd walk out from the tunnel.

11 I Am The Resurrection

The music supposedly began as “a pisstake” of Paul McCartney’s bass on The Beatles’ Taxman, according to Reni. “Mani would play the riff backwards during soundchecks and we played along over the top for a laugh. Finally, we said, ‘Let’s do this joke song properly and see what happens’.” Its drum intro, chords and ‘vibe’ also bear resemblance to The Light Pours Out Of Me by fellow Mancunians Magazine (1978). Its blissed-out Brown-on-bongos coda was the perfect E’d-up end to a Roses live rave; in the studio, it took three days’ rehearsals to piece it together for mostly live recording: the circular acoustic-guitar arpeggio before the strafing coda was fed via a ‘ghetto blaster’ as a backing loop for the band to improvise around.

The Stone Roses is an odd record, in many ways. It was the culmination of five years of relatively low-key work, even if the band were all-that-time circling the big shots of Manchester music. On its release, drummer Reni was the youngest at 25: the others were already 26. In comparison, Johnny Marr had split The Smiths at 23. And it was also the mother of false starts: the Roses hit the buffers not long after.

There’s an over-romanticised story about Ian Brown and John Squire’s joint ‘destiny’, having first met as toddlers in a sandpit. The crux is true, though the two weren’t friends until their teens, when music brought them together. Squire had begun playing guitar with some seriousness from around 15, liking The Byrds and The Beatles.

Via Brown, who also played rudimentary bass, he got into Clash and Sex Pistols records, and soon learned to play those, too. Brown liked his punk, but also reggae and Northern Soul.

Squire and Brown played briefly together in The Patrol, but by the time the Roses were taking shape, Alan ‘Reni’ Wren was different again – a wunderkind drummer who could also sing and play guitar, and whose favourite bands in his teens were Van Halen and Led Zeppelin.

It took a while, but the Roses’ first attempt at recording was in 1985, when they got help from local producer hero Martin Hannett. Back then, the Roses had a second guitarist, Andy Couzens, and Pete Garner on bass, and were still in search of an identity.

The harsh sessions with Hannett only amounted to six nights and were hardly a success. So Young duly came out. It was alright, in a flailing post-punk/Theatre Of Hate sorta way, but ripples extended only through Manchester. By the Roses’ next recording, Manchester was changing: the city’s bards of boredom, The Smiths, had split. Hip-hop and early house were beginning to take over and The Haçienda was gathering a crowd.

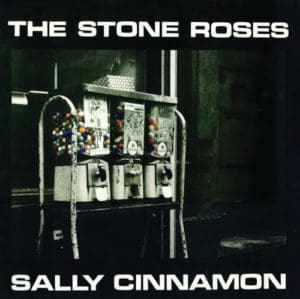

“The summer of 1987 is when everything changed,” Shaun Ryder later remembered. “When life suddenly went from black and white to Technicolor. When we first got the E.” The nascent ‘Madchester’ scene was gelling by the time the Roses cut their second single, Sally Cinnamon. They produced it themselves, with soundman Simon Machan, and while it still sounded rather wiry, it did show a growing savvy for hooks and tight rhythms.

The band quickly sold out 1,000 singles in their hometown, and those local ripples were building to a new wave. For his part, Noel Gallagher remembers his 20-year-old self thinking: “When I heard Sally Cinnamon for the first time, I knew what my destiny was.”

Couzens and Garner were jettisoned in ’86 and ’87 respectively – Mounfield, who the band had known for years and who’d regularly watch them as a fan – came in on bass. They pushed on, building a loyal fanbase and by their third single, 1988’s Elephant Stone, The Stone Roses had arrived proper.

It had the kudos of New Order’s Peter Hook as producer (“I would have done it for free”); Mani and Brown started bombing Manchester with Stone Roses graffiti; Elephant Stone featured Squire’s Pollock-styled art for the first time; they continued their strategy, rave style, of playing warehouses over established venues.

Read more: Top 40 Debut Albums

Read more: Shaun Ryder interview

They’d turn up in their newly adopted garms, too. Leo Stanley, owner of Manchester clothes shop Identity, who was then kitting out a lot of the Manchester bands, told The Guardian: “In 1988, Ian Brown asked if we could get any Wrangler flares as they were really hard to get hold of. As soon as Ian walked on stage wearing flares, everyone wanted them.”

That was part of their appeal. As über-fan Noel Gallagher recalled: “The Roses sang in Manchester accents, they wore the same clothes, they went to the same clubs, you could see them down the same shops where you were buying your desert boots and your flared jeans.”

It would be wrong, though, to hail the Roses as forward-thinking messiahs. That early struggle for identity was there and the Roses had their own dancer/‘vibemaster’, Cressa, duplicating the role of Bez in a straight steal from Happy Mondays. He’s on the back cover of The Stone Roses.

With its breakbeat-like drums from Reni and leaping, Beatle-esque melodies, Elephant Stone nailed their sound. Yet love didn’t spread all around. Gob-around-town and svengali Tony Wilson reportedly quipped that if you gave 1,000 monkeys guitars and Jimi Hendrix songbooks, they’d eventually emerge sounding like The Stone Roses. Touché. Though, of course, Wilson was likely just riled that Factory’s Happy Mondays boasted little of the Roses’ purer pop charms.

By 1988, they had enough for a solid demo that they were happy with. It went first to Rough Trade, where label boss Geoff Travis (who’d previously helped steer The Smiths’ career) judged: “They were just brilliant, fully formed, great songs… the thing that was really wonderful was that the rhythm section was such an elastic dancing creature, which very few great rock ’n’ roll bands seem able to achieve.”

With their soon-to-be-infamous manager, Gareth Evans, the Roses were still blagging somewhat: they didn’t sign long-term with Rough Trade, but instead went to Zomba offshoot Silvertone.

“We wrote most of the first album in a few weeks, because we’d blagged the record company,” Brown told NME in 2009. “We told Silvertone that we had about 30 or 40 songs, but we only had about eight.” But, again, those eight songs were enough. When producer John Leckie was passed their demo by Silvertone, it featured solid run-throughs of Waterfall, She Bangs The Drums, This Is The One and I Am The Resurrection. All that had to be done, really, was deliver it all as well as possible.

The Stone Roses is not a ‘dance’ album, but there is some dance sensibility to it. Battery Studio’s in-house engineer, Paul Schroeder, was perhaps a crucial figure – because he was steeped in mixing dance records, he brought his EQ-ing and tech setup to that process intentionally. He worked closely with Reni and Mani to ensure both had sufficient punch and clarity in the rhythm-section mix.

John Leckie’s job was guiding the whole thing. He made sure the songs all had focused openings and, mostly, definite endings. The Roses liked Leckie. His work with George Harrison and XTC offshoot the Dukes Of Stratosphear were big ticks, as was him citing his favourite record to be Love’s Forever Changes (Leckie later admitted he said it off the top of his head).

By turn, Leckie later said (fondly) of the band that: “Even though there is a punk heritage, they’re hippies. Ian especially. It sounds corny, but there’s a lot of love there, and you don’t really get that with other Manchester bands.”

‘The rhythm section was such an elastic dancing creature, which very few great rock ’n’ roll bands seem able to achieve’

Brown has said Leckie’s brief was to “get the ultimate live version, but with a twist” and the producer himself recalled a relatively straightforward process. “There wasn’t any pressure to prove themselves, they knew they were good,” he told The Quietus.

As for the perceived weakness of Brown’s voice, Leckie had no problems. “To me, he was no different to any other vocalist,” the producer told Sound On Sound. “He’d perform, say, four takes, and I’d comp them and bounce them down. It certainly wasn’t a nightmare. He’d always get what we wanted within a couple of hours… and back then, you have to remember, there was no Auto-Tune.”

But Leckie continued: “They weren’t technically aware. They never touched the equipment, or sat at the desk and twiddled the knobs, or said: ‘Why don’t you try this?’. If they didn’t like something, they’d say.”

As the bassist said in 2007, before their reunion: “I’m the only person who could bring it back together again… I don’t know if any of us are powerful without each other. The magic was the power of four.”

And what power. With those formative years spent gigging, writing, rejecting, honing, The Stone Roses were ready. All in, although split between four different studios from October 1988 to March 1989, The Stone Roses took just 55 working days to complete.

Hunter S Thompson once wrote about mid-60s San Francisco that: “You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning…” The same sentiment definitely applied to Manchester in the late 80s. Happy Mondays were, of course, very different, musically, but northern neighbours The Charlatans drew heavily from their well. Noel Gallagher reckons Oasis wouldn’t even exist without the Roses.

But The Stone Roses had something mighty that set it apart from all the rest. As Shane Meadows’ man says: “You know and I know, but you can’t write it down, can you?”

The Roses bloomed all too briefly, of course. Recording injunctions, writer’s block, a usurping by young Princes Noel and Liam, and a wayward mountain bike (leaving Squire with a broken collarbone and a cancelled Glastonbury headline slot) saw them split by 1996. John Squire later said 1994’s Second Coming is “more like we wanted to sound”; Ian Brown demurs, arguing: “We lost the light”.

More than three decades on, The Stone Roses still haven’t matched it – and it seems likely they never will. Their short-lived comeback ended without that promised third album. But it doesn’t matter. This is the one.

Read more: Making The La’s

Read more: Pete Burns – The Final Interview

Want more from Classic Pop? Become a subscriber. Click here for more details.

The Songs

The Songs