Prince: Giving It All Away

By John Earls | August 1, 2019

The new posthumous Prince album Originals is the clearest insight so far into just how varied his mind was, able to write for musicians from Kenny Rogers to The Bangles while he was also “trying to make his friends famous” by giving them classic songs. In a wide-ranging investigation into his working methods, Classic Pop speaks to the woman who helped make Prince’s magic happen, two of Paisley Park’s finest singers… and the man in charge of the Purple One’s golden vaults to see what’s next.

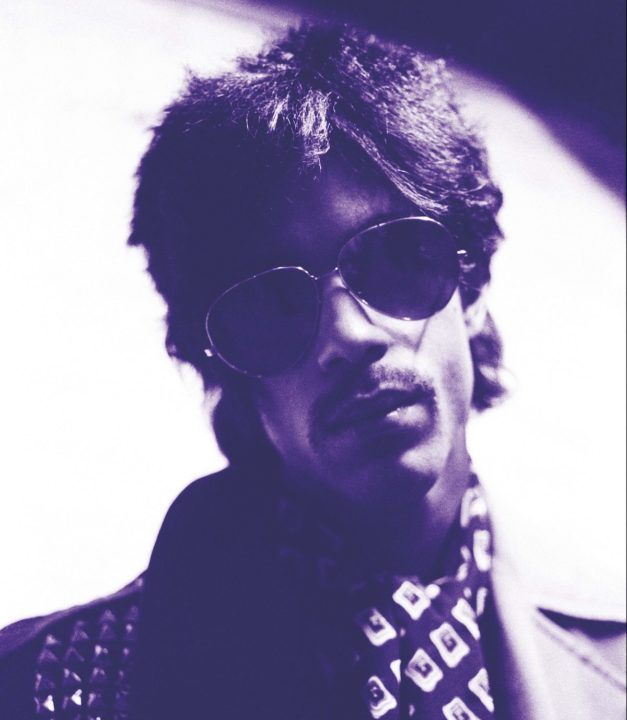

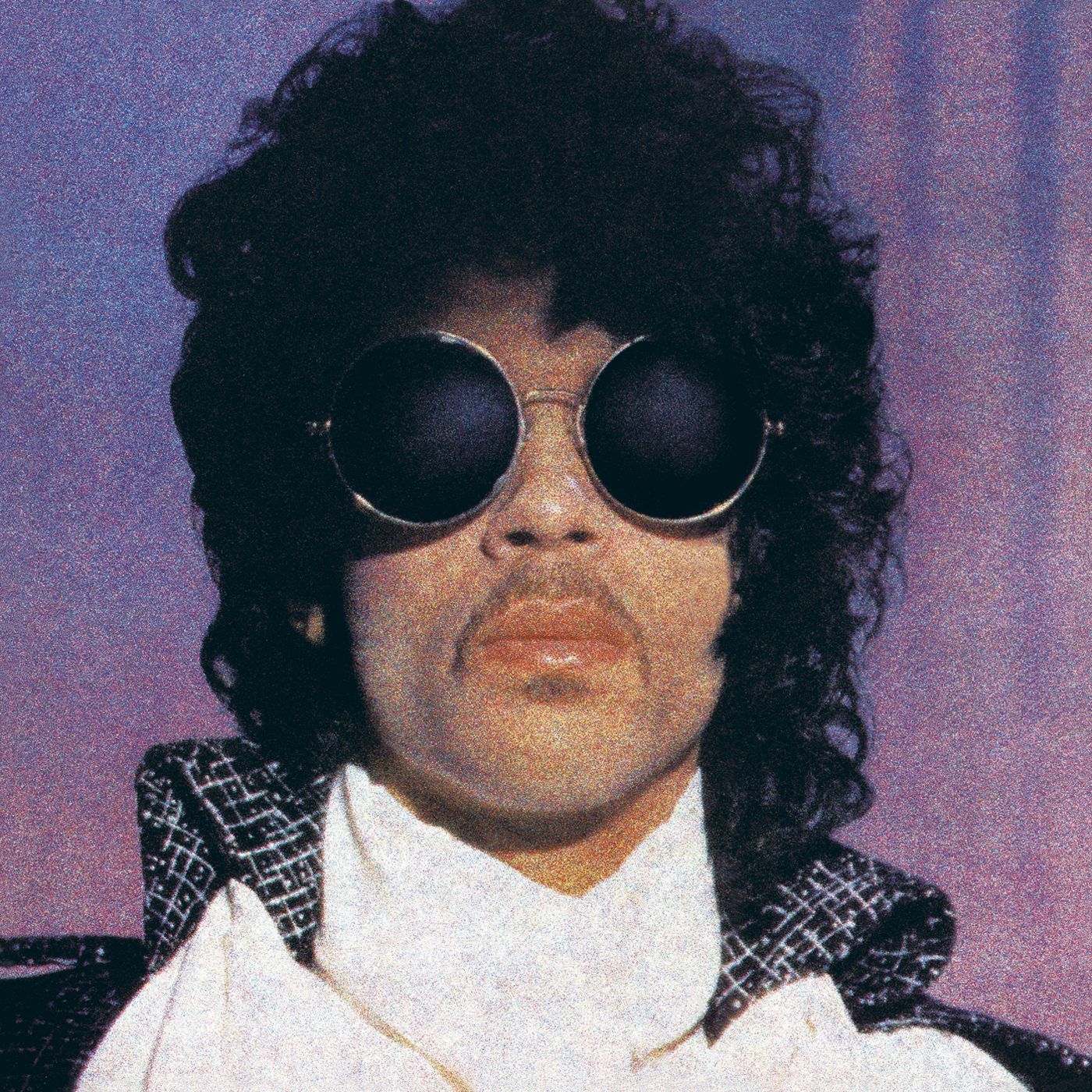

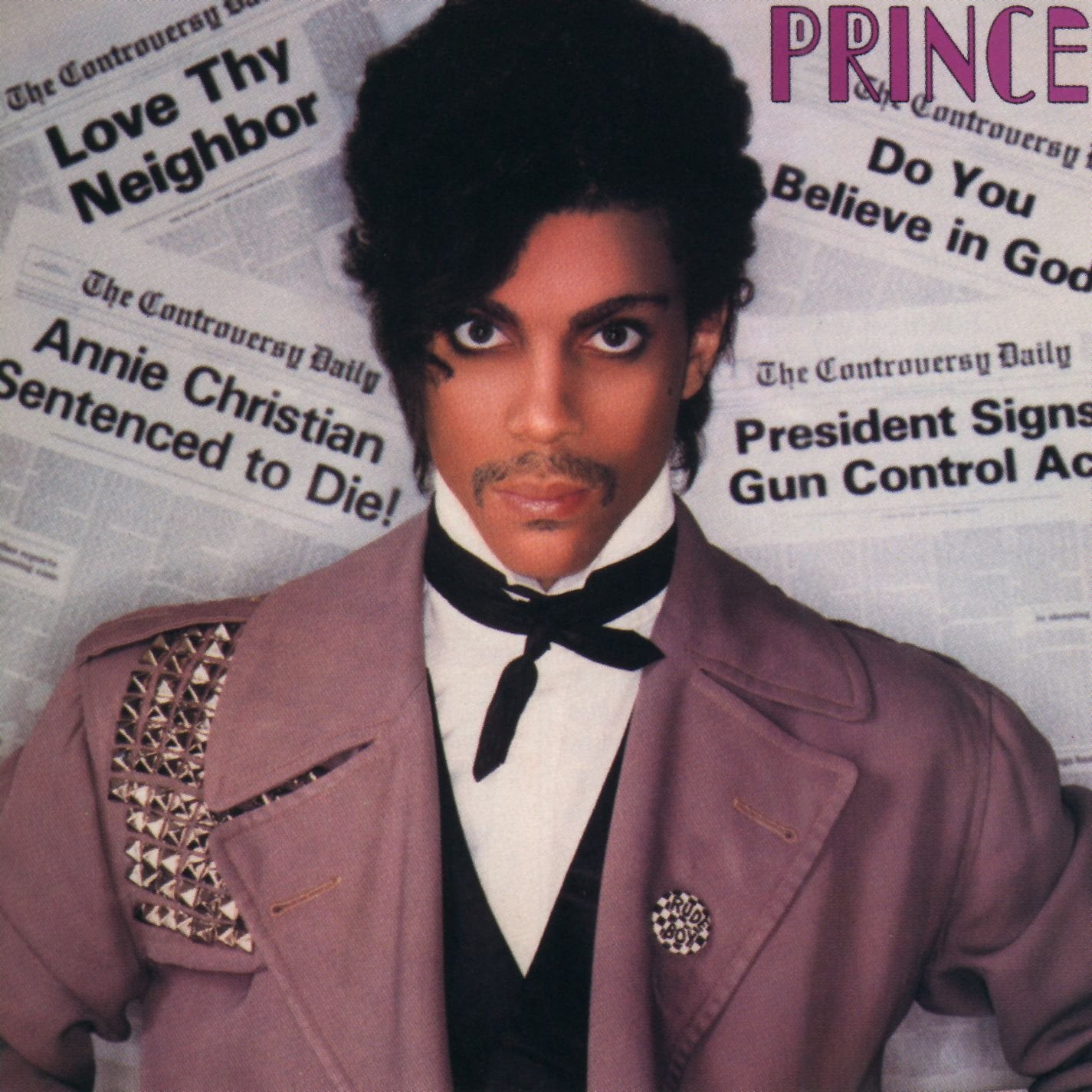

The name Peggy McCreary isn’t widely known outside of Prince’s hardcore fans. Yet, arguably, Prince’s golden 80s albums would have sounded a lot different without her. Starting with Controversy in 1981, Peggy was Prince’s studio engineer for five years, on call for His Purpleness 24/7 whenever he wanted to record at Sunset Studios in Los Angeles.

At Sunset, Peggy also engineered for Janet Jackson, Elton John, Tom Waits, Van Halen… she was used to stars’ stringent demands. Prince’s work rate meant he was on another level. Because Prince could play everything himself, he was able to get his songs down as quickly as the music was flowing through him. And in the 1980s, Prince’s music was literally unstoppable. Having worked until 5am one day in 1984, even Peggy’s patience was tested when Prince phoned five hours later and said he wanted her back in the studio at midday. “I was so irritated with him,” admits Peggy. “I was going to him, ‘Really, dude?’ When Prince came in the studio, he strutted in and said, ‘I said to myself, if I dreamed another verse, I was coming in.’” By then used to how readily songs came to Prince, Peggy was still taken aback. “I asked him, ‘You dream your songs?’ and he said, ‘Sure, sometimes…’” That song was Manic Monday. By the end of the day, the track was finished.

Speed Is Of The Essence

Such a hectic schedule was typical – virtually all of Prince’s songs were recorded in a day. Peggy speaks admiringly of his intensity, saying: “People ask me, ‘What was Prince’s formula?’, but he didn’t have one. What I feel is really, really important to say about his music is how quickly he did it. Normally, you’d cut basic tracks for 10 songs, bring different musicians in and then you’d mix it – sometimes for months and months. But with Prince? He’d come in at midday, we’d start a song and we might do a rough mix at 3am then finish it the next day. But usually, we’d complete it the same day and there it was: gone, done, fresh.”

Virtually any other musician would have kept a brilliant pop moment like Manic Monday for themselves. New posthumous Prince album Originals is a reminder of just how many great songs Prince was happy to give to his friends and a very few select group of outsiders like The Bangles. All of Originals’ 15 songs bar Martika’s 1991 hit Love… Thy Will Be Done were written by Prince between 1981-85, when he also made 1999, Purple Rain and Around The World In A Day for himself. Last November, the Prince estate released his original version of Nothing Compares 2 U as a standalone single: the video, of Prince dancing in the studio, notched up eight million views almost immediately.

‘Prince didn’t have anyone else to turn to. Prince could project himself as the artist you wanted him to be.’

Expanding the idea into a full album of the songs Prince wrote for others seemed an obvious move. As the archivist for Prince’s estate, Michael Howe is the man responsible for cataloguing Prince’s vast array of unreleased music. Working alongside the estate’s entertainment advisor Troy Carter and creative director Trevor Guy, Michael compiled Originals. “Prince was a creative titan,” says Michael. “On Originals, you see his general ability – not just as a performer, but also in production, arranging, writing. We’re focusing on songs that are particularly interesting, either because they were substantial hits for other artists and are relatively familiar, or it’s a little less obvious and showcases another side of Prince’s artistry unfamiliar to anybody bar the most ardent fans.”

Expanding the idea into a full album of the songs Prince wrote for others seemed an obvious move. As the archivist for Prince’s estate, Michael Howe is the man responsible for cataloguing Prince’s vast array of unreleased music. Working alongside the estate’s entertainment advisor Troy Carter and creative director Trevor Guy, Michael compiled Originals. “Prince was a creative titan,” says Michael. “On Originals, you see his general ability – not just as a performer, but also in production, arranging, writing. We’re focusing on songs that are particularly interesting, either because they were substantial hits for other artists and are relatively familiar, or it’s a little less obvious and showcases another side of Prince’s artistry unfamiliar to anybody bar the most ardent fans.”

Michael cites You’re My Love, a lounge ballad written in 1982 for country icon Kenny Rogers, as a prime example of just how diverse Prince’s talents were. “You’re My Love is a very un-Prince-like proposition,” Michael laughs. “But it’s so interesting to hear him do something that’s basically a Holiday Inn lounge vibe. It’s a peek into an area of Prince’s artistry most people probably didn’t know even existed.”

Oh! Susannah

Someone well aware of how varied Prince’s talents could be is Susannah Melvoin. The twin sister of The Revolution guitarist Wendy Melvoin, Susannah was the keyboardist in The Family, the band formed at Paisley Park following The Time’s split. Susannah was also Prince’s girlfriend – he wrote Nothing Compares 2 U when he missed her while The Family were recording their album. “The song Prince wrote for Kenny Rogers is typical of his diversity,” Susannah explains. “It’s like he’s his own writing company. Most of these places would have 15 staff songwriters, each with their own specialty, so if a call comes in saying, ‘Kenny Rogers is looking for a track’, you’d give it to the country writer. But Prince didn’t have anyone else to turn to. Prince could project himself as the artist you wanted him to be. When he created a track, it’d have the essence of a Prince song, but he’d so effortlessly and so brilliantly write something for you that you’d come away thinking, ‘Oh yeah, I can do this track.’” Nowhere was that better exemplified than on Nothing Compares 2 U. While Susannah was a backing vocalist on the rest of The Family’s self-titled 1985 debut album, on Nothing Compares 2 U she’s the aching counterpoint to lead singer St Paul.

Susannah recalls how the song was written while Prince was in rehearsals for the Purple Rain tour and recording Around The World In A Day: “Imagine – he’s in rehearsals all day long, then he goes to the studio and he’s there all night doing this completely different song. He could switch his brain on and off like that. To be both that focused and to allow yourself to be that creative, it’s an extraordinary ability.”

Susannah recalls how the song was written while Prince was in rehearsals for the Purple Rain tour and recording Around The World In A Day: “Imagine – he’s in rehearsals all day long, then he goes to the studio and he’s there all night doing this completely different song. He could switch his brain on and off like that. To be both that focused and to allow yourself to be that creative, it’s an extraordinary ability.”

Susannah flew from Minneapolis to LA to record her vocal with The Family producer David Z, older brother of The Revolution drummer Bobby Z. David had heard Prince’s demo by the time Susannah arrived at the studio. “As soon as I got through the door, David was going, ‘Wait until you hear this track!’” Susannah laughs. “I was so moved and so honoured Prince had felt that creative and wanted it to go on our record. When you’re in an intimate relationship with somebody and also working together, and that person then creates something so extraordinary for you, you feel really connected to it. I wanted Prince to be proud that I could hold that song up. When I sing, ‘It’s been so lonely without you here,’ you can clearly hear me sing it to Prince.”

St Paul recorded his vocals separately back in Minneapolis. “David worked really hard with Paul to emulate Prince’s guide vocal,” explains Susannah. “They worked hours on it, David going, ‘Again…again… let’s do this one more time… again.’ Paul and I were two 19-year-olds trying to do what Prince wanted us to do, and I know Paul wanted to make his boss proud as well.”

Rage Hard

Another recipient of Prince’s love songs was Jill Jones. Her self-titled 1987 debut is widely considered to be the great lost album by a Paisley Park artist. Originals features Prince’s version of the centrepiece of Jill’s album, the sensual Baby, You’re A Trip. “I loved it when Prince did the more gospel-type songs,” says Jill. “When he kept things simple or when he’d rage in the vocal room all by himself, screaming these emotional thoughts, that was pure conviction. So when I heard Baby, You’re A Trip, I thought it was beautiful.” But it was also unsettling for Jill just how well Prince seemed able to read her mind. “Prince was writing from the point of view of someone who was starstruck. To be honest, I kept thinking, ‘Is he writing this from my point of view? Is this how he thinks I see him?’ It was mind-blowing, thinking somebody could know me so well. What girl ever wants a guy to know she loves him that much? It was a little like being completely naked.”

Being able to express himself in music was key for Prince, according to Susannah. Prince also wrote If I Was Your Girlfriend, Strange Relationship and In A Large Room With No Light about her. “I loved him, and I felt a connection to him as somewhat of a muse,” says Susannah. “Those songs were his way of communicating with me, of saying things he couldn’t otherwise say. I knew that at the time, so I feel a deep love and respect for him. To have been with somebody you love so much who you also work with, you’re both creative and you get to create together? As artists, that’s perfect.”

‘He could be tough, but he could be super-sweet. I never knew who he was, or who he was going to be.’

Peggy McCreary believes Prince’s desperate home life as a child also inspired him to keep creating. The singer had a troubled relationship with his stepfather, who kicked him out of the house as a teenager so that he instead lived in the basement of their neighbours, the Anderson family. “I think music saved him,” Peggy reasons. “He taught himself to play all these different instruments, and music was aching to get out of him for all those years, because he just never stopped.”

It was certainly a contrast to what Peggy was used to from other artists. “I’d worked with people before who’d had unreasonable requests, but they were usually drug-fuelled,” insists Peggy. “Prince’s never were. He lived on coffee – that’s all he ever lived on that I saw. He didn’t want to eat, because that slowed him down. Once those ideas were flowing, Prince tried to fulfil them as best he could, and that’s how I helped. That was my life.”

According to Jill Jones, one reason Prince’s music was so diverse is because the star showed a different facet of his personality to everyone he met. “Everybody served a different role to him,” Jill says. “He’d switch on to very different channels with the different people in his life. That’s why it’s very difficult to pin down the truth with Prince: some people will say, ‘He told me this’, other people will say, ‘But he told me that!’ and he may very well have said both those things. He never switched off unless he was sleeping, and he did very little of that. He’d sometimes binge-sleep.”

Jill wanted her debut album to be as diverse as possible, which she and Prince were aware would make her a difficult artist to sell in the mainstream. “If you’re an entertainer, you have to be very clear what you’re doing,” she reasons. “You have to be one-dimensional, in the sense that you can’t do it all. In my records, I wanted to do it all. Prince thought a lot about each personality he worked with. With Apollonia, he thought, ‘Let’s bring a bit of romance into it.’ It was a lot softer for her than for Vanity, where you get Make-Up. For The Time and their singer Morris Day, Jungle Love is all Prince’s alter-ego. If you hung out with Prince, he’d strut around and throw money at you. That wasn’t something he’d show to everybody, but he’d show it to Morris.”

That strutting, show-off side wasn’t something McCreary witnessed when they were working together. Or at least not in the studio. When Prince first worked with Peggy, finishing off the Controversy album, Peggy had been warned about him by Sunset Studios’ receptionist. “I’d never heard of Prince,” she laughs. “The receptionist said to me, ‘You can’t let him work with you on the weekend with nobody around.’ When I asked why, she said, ‘He writes such dirty songs, about giving head and all sorts of stuff!’ My impression of the person who’d walk through the door was not the same as the person who walked through the door. He was shy, polite and mumbled instructions to me. I finally got in his face and said, ‘If this is going to work, you’ve got to talk to me so I can hear you. Talk to me in my face and I’ll work for you.’” Prince’s lothario reputation never intruded in the studio, as Peggy says: “Believe me, I had enough of the male/female attention from other artists in the studio, but that wasn’t it from him. He was very respectful, at least in that way. There were certainly times when it got weird.”

As someone so driven, it was perhaps inevitable that it got weird whenever anything technical broke down. While making Purple Rain, Peggy was able to oblige when Prince decided at midnight that he wanted strings players in the studio there and then. But, on the same album, Prince’s arrangements were becoming more complicated. The only way to record 48 tracks on a song was to pair two 24-track studios together via a computer – which constantly broke down. “It didn’t work very well,” sighs Peggy. “You’d always have to call the maintenance man in, and that really frustrated him. He’d get really angry and he’d just leave. You’d go, ‘Oh, OK. I guess this session is over.’”

Party On

It was in the wake of Purple Rain’s success where Prince’s lifestyle became too much even for him. “He’d leave the  studio at 1am, then go clubbing,” says Peggy. “He’d call a session for noon that day, but he wouldn’t show up until 7pm, by which time I’d be exhausted. I finally said to him, ‘This is killing me. I’m here for eight hours before you get here, then you want to work until 4am.’ Prince said, ‘Yeah, but nobody will wake me up.’” Peggy cheerfully volunteered to wake Prince up so he’d get in the studio on time, so he gave her his bedroom extension phone number. But, out until 5am partying, Prince only kept to his new workload for a week. “He couldn’t keep that schedule, and when he stopped I thought, ‘Yeah! There you go!’”

studio at 1am, then go clubbing,” says Peggy. “He’d call a session for noon that day, but he wouldn’t show up until 7pm, by which time I’d be exhausted. I finally said to him, ‘This is killing me. I’m here for eight hours before you get here, then you want to work until 4am.’ Prince said, ‘Yeah, but nobody will wake me up.’” Peggy cheerfully volunteered to wake Prince up so he’d get in the studio on time, so he gave her his bedroom extension phone number. But, out until 5am partying, Prince only kept to his new workload for a week. “He couldn’t keep that schedule, and when he stopped I thought, ‘Yeah! There you go!’”

Prince would show colleagues kindness – he once came into the studio and took Peggy off to the cinema in a hired limo, still paying her for the day. But Prince in a bad mood was explosive. Peggy recalls working on a session for The Time, whose line-up included future production legends Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. “When Prince rode you pretty hard, that was a tough day,” recalls Peggy with considerable understatement. “One day with The Time, somebody had lost some tapes. It was nothing to do with me, but I didn’t know this at the time. Anyway, Prince was in the shittiest mood. Jimmy Jam was looking at me, going, ‘I’m sorry that this is at you, but thank God it’s not us.’ He could be tough, but he could be super-sweet. I never knew who he was, or who he was going to be.”

Sunset Studios had three recording studios in its complex. Peggy ensured Prince always had his favourite vocal booth, equipped with a vintage Neumann U47 vocal microphone with its own original supply: “That combination was just gorgeous on him.”

‘He was a single-minded guy with a clear vision of his artistry’

Unsurprisingly, Peggy was constantly pestered by other visiting musicians asking her to see if Prince would write a song for them. “Prince didn’t give songs away to people who weren’t under his control,” says Peggy. “His songs were his babies, they were his heart. He didn’t want his music to be bastardised or for anybody to mess it up. I knew the producer that one singer was working with, so I did ask Prince if she could get a song. Prince was walking out of the studio with me as she was walking out of the other studio. Prince turned to me and said, ‘Ooh, one of those loud broads,’ and walked back into the studio. He wouldn’t meet her.”

Jill Jones doesn’t believe Prince’s intention was to see which musicians he could control. “At first, it was an innocent little idea – ‘Let’s make my friends famous,’” she states. Slowly, however, Prince began seeing his songs for other people as, in Jill’s words, “alternate revenue streams”.

He began to get frustrated with Warner, partly because they in turn were under pressure from organisations such as MTV: when Jill and other Paisley Park artists’ records were out, they’d only get airplay if Prince would appear at MTV concerts and the like. She says: “Prince started to give songs to the up-and-coming pop singer, as a strategic move to leverage himself against Warner’s interests. It turned into, ‘OK, let me see who I can give this song to, so I can make some extra side money.’”

On The Spectrum

Prince rarely properly co-wrote with anyone in the 80s, but made an exception for Susannah. She feels their song Starfish And Coffee, on Sign O’ The Times, is key to understanding Prince’s gift. It was written about Cynthia Rose, an autistic classmate of Susannah’s who was also musically gifted. A piano prodigy, Cynthia now lives quietly in a sheltered community and remains good friends with Susannah. “Starfish And Coffee is about all these creative kooks who aren’t neuro-normal,” says Susannah, who is writing a children’s book about the song. “They have the ability to see the world in colours and metaphors, they have an emotional connection to their inner lives. Prince said, ‘Deep inside, this represents who I am.’ For Prince to connect to my story of this girl, it’s a great example of the tenderness of him. For all the rock stardom and bravado he could exude, there’s also this tender, tender man inside.” She continues: “Prince said before, ‘I’m autistic, I think I’m on the spectrum.’ It was a gift, this neuro-diversity, these unique ways of seeing the world. It’s vital to creative expression.”

Although Prince was so prolific and worked so quickly, he was still able to rein it in on occasion. One of the songs Michael Howe has found in Prince’s vault is the original version of When Doves Cry. Peggy recalls: “When we first made When Doves Cry, it was way too over-produced, way too grandiose, with synths and all sorts of stuff on. As the night went on, we started taking instruments out. At the very end, at 7am, Prince cut the bass. He said, ‘Ain’t nobody going to believe I’m going to do this.’ He could check himself. I remember grabbing the receptionist and saying, ‘You’ve got to hear this song!’ He knew some of his stuff was great. The songs he wasn’t so excited by, you’d never hear of them again.”

Although Prince was so prolific and worked so quickly, he was still able to rein it in on occasion. One of the songs Michael Howe has found in Prince’s vault is the original version of When Doves Cry. Peggy recalls: “When we first made When Doves Cry, it was way too over-produced, way too grandiose, with synths and all sorts of stuff on. As the night went on, we started taking instruments out. At the very end, at 7am, Prince cut the bass. He said, ‘Ain’t nobody going to believe I’m going to do this.’ He could check himself. I remember grabbing the receptionist and saying, ‘You’ve got to hear this song!’ He knew some of his stuff was great. The songs he wasn’t so excited by, you’d never hear of them again.”

It was Peggy’s responsibility to keep Prince’s studio log in order: a near-impossible task, given the pair had to be so focused on getting his music down. His unreleased 1982 song Colleen is so titled because Peggy asked him the name of the song they’d spent all day on, to record in the studio log. “What’s your middle name?” responded Prince. Colleen it was.

Some songs would go untitled for days, so Peggy would instead fill the logbook in with the names of songs worked on from the day before. “A lot of those records are incorrect, because Prince didn’t communicate the information,” admits Peggy, who left the music industry in 1986 to raise a family: “The best way to gracefully bow out.” The final occasion that she saw Prince was when her daughter Morgan, now 31, was eight months old. Peggy says: “He held my daughter, and that was the last time I saw him. That breaks my heart.”

None of which makes Michael Howe’s job as archivist any easier. Originals opens with the incendiary double holler of Sex Shooter and Jungle Love, as deliciously filthy as anything from Prince’s canon. “As a long-time Prince fan, I’m pretty well plugged into the very serious collectors,” explains Michael, a former Warner executive who worked closely with Prince near the end of his life. “I was surprised to find his version of Jungle Love, because that had never reared its head, to my knowledge. Sex Shooter was another mythical unicorn track. Being able to put those on Originals is pretty great.”

The Prince “vault” is actually a climate-controlled, natural disaster-proof office in Hollywood, filled with hundreds of analogue tapes. Many of them are incorrectly labelled and, over two years after he became Prince’s archivist, Michael is still finding surprises “every single day”. “We’re proceeding with as much completeness, respect and integrity as Prince would demand,” says Michael. “What you hear on Originals is the way a cleaned-up master would sound. There’s no consideration to compete with the vagaries of the 2019 pop marketplace. We approached this as if we were sitting in Sunset Sound in 1983 or ’84. Approaching this stuff is a sacred process.”

There is a plan for further posthumous Prince releases over the next “three-to-five years”, which can be changed if Michael finds anything in the interim that simply can’t wait. Prince said he expected his unreleased material to emerge after his death, but didn’t leave detailed instructions as to how it should appear. “You can never answer the question fully,” Michael admits.

“We knew Prince pretty well, for what we think would be appropriate. He was a single-minded guy with a clear vision of his artistry. At the top of our list is ‘Is this the calibre of what Prince would want in the marketplace? Would he approve of this if he were here?’ We hope we’re doing the right thing.” The songs on Originals wouldn’t fit on Prince’s albums from the era. Yet it also sounds like a lost Prince album from 1984. The vault seems in safe hands.

Originals is streamed exclusively on TIDAL on 7 June, then released on vinyl, CD and general streaming on 21 June. A deluxe CD/LP boxset features sleevenotes by Peggy McCreary and Susannah Melvoin.