Talk Talk albums – the complete guide

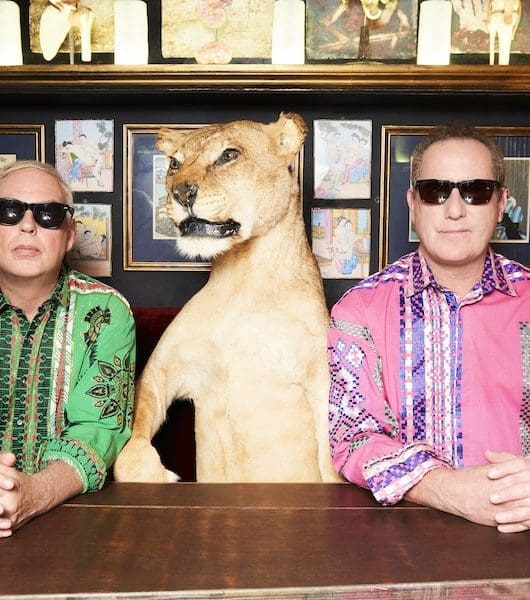

By Steve Harnell | February 20, 2025

Over five studio albums, Talk Talk ventured into evermore experimental sonic territory to pursue their uncompromising artistic vision…

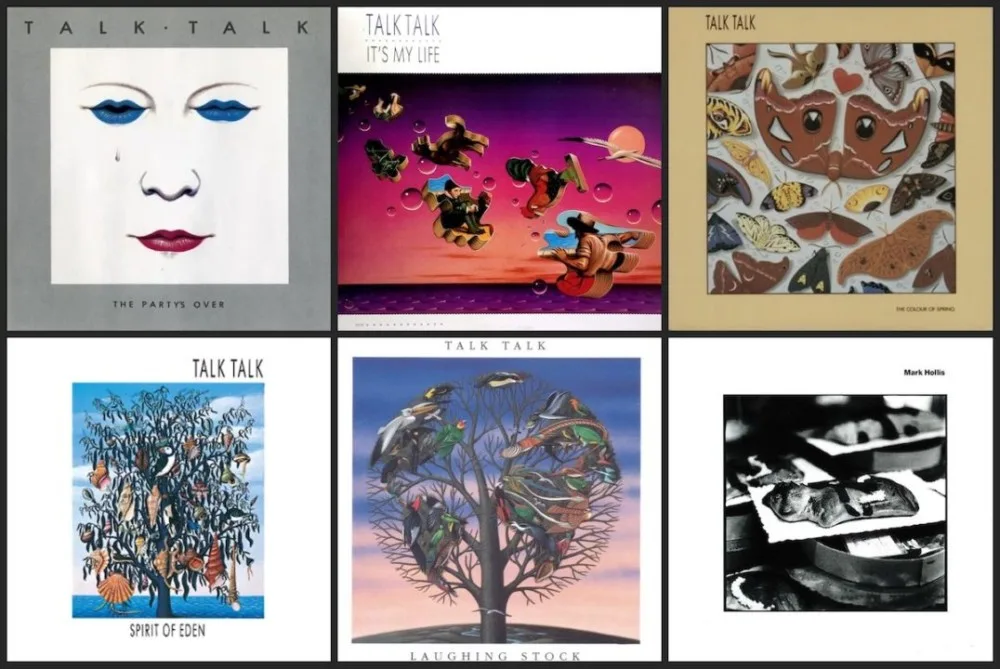

The Party’s Over

The Party’s Over

Released July 1982

Recorded 1981-1982

Label EMI

Chart Position UK No.21 and US No.132

For the majority of their extraordinary, ground-breaking career, Talk Talk’s music was timeless and visionary – free of the shackles of faddish genres and living in a rarefied weightless realm of its own making. But their 1982 debut is very much of its time, an early-80s fretless bass sound imbued with strident synth textures. It was, ironically enough, a totemic example of the New Romantic movement that frontman Mark Hollis in particular grew quickly to loathe and set about kicking against.

There was, though, always something ‘other’ about this London outfit. They may have been groomed as poster boys in the same mould as Duran Duran but they were cut from very different cloth.

Hollis’ mournful croon – he was happier namechecking Otis Redding as an influence than any of his contemporaries – and even the downbeat, cynical title of this debut is evidence of this; The Party’s Over is hardly the call-to-arms that many bands would announce their arrival with.

Hollis had previously dipped his toe into punk-pop with The Reaction – they released their only single I Can’t Resist in June 1978 – before forming Talk Talk. He brought a much wider range of influences to the table; experimental jazz icons John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, plus prog rock mainstays King Crimson and Pink Floyd.

Early Talk Talk demos were produced by Jimmy Miller, an unlikely foil who had previously helmed classic-era Rolling Stones and Traffic albums among others. For their debut, though, EMI turned to Colin Thurston, a veteran of the spiky likes of Magazine, but more pertinently the man who had produced Duran Duran’s eponymous first LP.

Timeless & Visionary

Talk Talk’s paymasters were keen for them to position themselves as a thoughtful faction within the New Romantic movement. The band supported Duran during an extensive winter tour of 1981, an experience Hollis found thoroughly dispiriting when faced with the fervour of a rabid mainstream pop fanbase.

Thurston threw every 1982 production trick in the book into the mix: electronic drums, a Fairlight synth, fretless bass and fake strings. However, the songs and arrangements remain singularly strong with Talk Talk and Candy in particular rising above their synthetic surroundings.

The former opens the album as a canny exercise in brand awareness with a hooky “Hey! Hey!” refrain in the intro. The Monkees, they very much aren’t, though. In fact, Talk Talk could be argued to be a lyrical takedown of the New Romantic movement itself, railing against its superficiality.

The introspective It’s So Serious is pure synth-pop with a decidedly downbeat pallor: “I’ve given everything, With nothing in return.”

Paul Webb’s bass-playing on Today, while excellent, is locked into the era – a style that would be almost trademarked by super session man Pino Palladino. There’s evidence of Hollis’ punky roots on Hate and he casts himself as a societal misfit during Have You Heard The News, sitting outside the glamorous frontman characterisation of contemporaries Le Bon and Hadley. However, the epic grandiosity of closing ballad Candy proved they could swoon with the best of them.

It’s My Life

It’s My Life

Released Feb 1984

Recorded 1983

Label EMI

Chart Position UK No. 35 and US No.42

Although Colin Thurston piloted debut The Party’s Over to a hair’s breadth outside the Top 20 in the UK album charts, announcing Talk Talk’s arrival in some style, Hollis was dissatisfied with the way he’d softened the band’s live sound.

Chris Thomas – the seasoned producer who had overseen albums by Roxy Music and Never Mind The Bollocks by the Sex Pistols, was in the frame to work on album two as was Rhett Davies, the producer/engineer with a sterling track record of collaborating with Brian Eno, Roxy Music, and who’d recently teamed up with OMD on Dazzle Ships.

Davies had already worked with Talk Talk on My Foolish Friend, a grittier sounding non-album track released as a single in 1983 that failed to chart in the UK but did respectable business in Europe, making No.7 in Italy and illustrating how they were beginning to emerge as major players on the Continent.

For the It’s My Life album, Hollis sought a more pristine vocal sound, tougher rhythm section and wanted the synths placed lower in the mix – his desire for a more natural approach free of synthetic intervention was beginning to show itself.

Change Of Direction

The album marks a key point in the band’s development, too, as original keyboardist Simon Brenner departed. Ostensibly, Talk Talk were down to a trio of Hollis, Webb and drummer Lee Harris, but unofficial fourth member Tim Friese-Greene would become Mark’s main co-writer as well as the band’s keyboardist, programmer, musical arranger and producer.

Hollis was impressed by the diversity of Friese-Greene’s production CV; he created novelty hit The Lion Sleeps Tonight by Tight Fit and worked with The Nolans, Thomas Dolby and Blue Zoo.

By now, Talk Talk had wholly discarded any links with the New Romantic movement – It’s My Life retains elements of synth-pop but it’s less obviously trend-chasing than its predecessor.

Much misunderstood opener Dum Dum Girl is a heartfelt anti-prostitution protest song and the downbeat Such A Shame sees Hollis turn to one of his favourite books for inspiration, The Dice Man by Luke Rhinehart. The subversive and controversial novel told the story of a psychiatrist who decides the course of his life on the roll of a dice. Hollis was intrigued by the chaos that methodology would bring to one’s existence.

The title track, arguably the band’s first gilt-edged classic, has a wonderful maturity to it and boasts one of Friese-Greene’s finest maximalist productions. By now, Hollis’ thoroughgoing confidence as a soulful vocalist shines through on the likes of Tomorrow Started and Does Caroline Know.

Mike Oldfield’s bassist Phil Spalding makes an uncredited appearance on The Last Time – Hollis and Friese-Greene’s multi-take approach to his session would be a working practice they’d take to exhaustive extremes on subsequent albums.

The Colour Of Spring

The Colour Of Spring

Released Feb 1986

Recorded Battery Studios, Videosonics Studios, 1985

Label EMI

Chart Position UK No.8 and US No.58

The watchword for album three is ‘organic’. “That whole synth side – get it in the bin!”, Hollis told interviewer Jim Irvin in 1997 about its change of direction. He was similarly combative about synthetic instruments a decade earlier, no doubt angering Electronics And Music Magazine as he proclaimed to their journalist: “I absolutely hate synthesisers. If they didn’t exist, I’d be delighted.”

The band were happy to excise all vestiges of synth-pop from their sound and The Colour Of Spring would become their biggest-selling album.

It sits at the apex of the melodic, conventional songwriting approach of their first two albums and the more experimental ambience of remaining efforts Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock. The perfect midpoint, in fact, and often underappreciated amid the remarkable affection in which those last two LPs are held.

As would become de rigueur for Talk Talk, the album was painstakingly assembled in the studio with a huge array of guest musicians. At their most focused, Hollis and co-writer Friese-Greene would be in the studio in 12-hour shifts, six days a week, during sessions that lasted nine months.

Organic Approach

Texturally, piano, organ and guitar dominate as the band imbue a more natural musicality into lyrical preoccupations with pastoral themes. Hollis namechecked classical composers Debussy, Satie and most prominently Bartók throughout recording sessions, with all contemporary influences given short shrift.

Session players were given little or no guidance as to what to play, leading to a multitude of takes being consigned to the cutting room floor. Three big-name contributors all come into play on the astonishing opener Happiness Is Easy – Steve Winwood on organ, double bassist Danny Thompson and guitarist Robbie McIntosh.

It’s an emotive melange of deft percussion, Thompson’s wriggling bassline, flamenco flourishes and opaque lyricism, made even more affecting by the arrival of a children’s school choir (“Little ships of Galilee/ Jesus tried to love us all/ Be a friend to me”).

Hollis is at his most thoughtful on I Don’t Believe In You, a wracked heart-on-the-sleeve evocation of a relationship in decay and McIntosh adds wonderful FX-laced guitar textures to its mid-section.

Commercial Success

A Tomorrow Never Knows for the 80s, Life’s What You Make It is built on an unwavering rocking 10-note piano riff that continues throughout the whole song. As the track ebbs and flows, stunning piano and guitar solos flash into the mix while that underlying riff continues beneath, the skeleton of an iconic anthem-in-the-making. Band manager Keith Aspden was concerned the album lacked a hit, so Hollis and Friese-Greene answered the challenge with this. Job done.

On the haunting April 5th, Hollis loses himself in almost wordless reverie. There’s an abrupt change of pace for the pulsating Jean-Paul Sartre-inspired Living In Another World, with Winwood whipping up a maelstrom on Hammond. Mark Feltham – later to work with Oasis – supplies bluesy harmonica.

There’s a gritty defiance to the percussive Give It Up and Hollis brings his love of Bartók to bear on the striking intro to Chameleon Day, which morphs into an echo-drenched piano ballad boasting one of the singer’s most dynamic performances; hushed whisperings one minute, gut-wrenching roars the next.

Spirit Of Eden

Spirit Of Eden

Released 16 Sept 1988

Recorded Wessex Studios, London, 1987-88

Label Parlophone (EMI)

Chart Position UK No.19 and US

The worldwide commercial success enjoyed by The Colour Of Spring was a game-changer on two levels for Talk Talk – it gave them the underlying confidence to explore the furthest reaches of their creative imaginations, and equally importantly it provided them with the financial security to pay for it.

On a flight back from Spain in September 1986 following the Colour Of Spring tour, Hollis had told manager Keith Aspden that there would be no more live shows – Talk Talk would be a studio-only band. April 5th and Chameleon Day had been an indication of the ethereal new direction that Talk Talk would embrace on Spirit Of Eden, one where the space between the notes was as important as the notes themselves.

Phill Brown was installed to engineer the sessions, a trippy hinterland designed to recreate the blissed-out recording environment of Colour Of Spring alumni Steve Winwood’s band Traffic – (“1am, November 1967”).

Aspden tells Classic Pop: “All the windows had been blocked and the studio was in darkness. Oil projectors, coloured washes and bubble lamps created a late 60s psychedelic atmosphere. Musicians were asked to improvise with minimal guidance and the many various interpretations were later reviewed and compiled, after much experimentation.

Freedom To Explore

“It was a long, exhaustive process requiring seemingly endless amounts of studio time, much of which was discarded in the final editing process – only the essential elements were allowed to remain.

“It was a very contentious and bruising way of recording, which at the same time helped capture a freedom of performance and interpretation that was Mark’s main obsession.”

Once again, multiple session musicians were utilised – a returning Danny Thompson and Robbie McIntosh plus many more, including violinist Nigel Kennedy. Session players were asked to record eight takes over pre-assembled drum tracks that would form the basis of the six ‘songs’ on the album; by now, though, all conceptions of traditional song structure had been jettisoned.

With no time constraints or even consideration of budget, the Spirit Of Eden sessions at Wessex Studios in London would stretch over the course of a year. As Aspden explained: “With just Tim and Mark involved, there was no balance, no big picture. They took the reins and drove the coach and horses right off the cliff.”

But what a beautiful freefall into oblivion it was. Sessions were invitation-only affairs – the band’s record company EMI were kept very firmly at arm’s length although they were well aware of the nature of the experimentation at hand, and its spiralling costs.

Every conceivable overdubbing option was explored by the band; Friese-Greene eventually worked out that he could make Hollis hit the delete button on disputed contributions merely by mentioning it “sounded a bit like Kajagoogoo”. It was a neat and efficient workaround.

A Law Unto Themselves

“The world’s turned upside down” begins Hollis on mesmeric opener The Rainbow where the vocalist shares centre stage with wonderful contributions from harmonica player Mark Feltham, delicate guitar work and stunning chordal transitions on piano that take the breath away.

Hollis’ lyrics are oblique, half-murmured and illusive – by now he was more interested in the sound of the words themselves than any explicit meaning.

The ambience is continued seamlessly into Eden, atonal notes teased out of various instruments before clanging guitars coalesce into something approaching a conventional structure and Lee Harris’ insistent, yet understated percussion gives it further shape.

It’s that slashing guitar that lifts this into the stratosphere, battling for space with Hollis in the mix (“Everybody will need somebody to live by/ Rage on omnipotent.”)

Church-like hymnal organ chords usher in the arrival of Desire but the peace is stunningly interrupted on two occasions by a tumult of organ, guitars and even cowbell. By the end, it’s a controlled cacophony of slashing, swirling chaos.

The impressionistic lyricism of Inheritance returns us to some kind of emotional equilibrium, a little shelter from the preceding storm.

The devastating I Believe In You, inspired by Hollis’ elder brother Ed and his battle with heroin addiction, is made even more poignant when you learn of his death shortly before the release of Spirit Of Eden.

A plaintive, mournful Wealth closes the album on a hushed note (“Take my freedom for giving me a sacred love”). Hollis sounds battered, yet unbowed.

“Once upon a time Talk Talk were a pop band,” mused long-time fan Betty Page of Record Mirror. “Now they’re a law unto themselves.”

Laughing Stock

Laughing Stock

Released 16 Sept 1991

Recorded Wessex Studios, London, 1990-91

Label Verve, Polydor

Chart Position UK No.26 and US

Following the collective shrug that greeted their masterpiece, Spirit Of Eden (it scraped into the Top 20 at No.19 and associated single I Believe In You stalled at No.85), Talk Talk would have been forgiven for shutting up shop once and for all. But after a period spent licking their wounds, Hollis and Friese-Greene returned more defiant than ever, determined to build upon and refine the extraordinary approach to recording for what was to be their final album, Laughing Stock.

The fact that as many as 50 session musicians contributed to Talk Talk’s fifth album but only 18 made it to the final master version is testament to the amount of material jettisoned in pursuit of sonic perfection.

By now, Talk Talk were down to the duo of Hollis and Harris, with unofficial member Friese-Greene maintaining his position as a central part of the studio outfit. Paul Webb had decided to quit after the exhausting Spirit Of Eden sessions.

After leaving EMI, Talk Talk signed to Polydor offshoot label Verve – Hollis was impressed by the fact the Mothers Of Invention once had a home there.

The now-legendary sessions for Laughing Stock were an even more extreme distillation of the working practices of Spirit Of Eden. Retaining the process of recording in near-permanent darkness, some contributors were pushed to the point of mental breakdown. It’s been noted that for every minute heard on the final album, an hour’s worth of material was dispensed with.

Defiant Determination

In an interview with John Pidgeon at the time of the album’s release, Hollis explained: “The first time something is played it is at its finest, and the minute you try to recreate that it becomes an imitation of something that was originally better. The problem with improvisation is that it meanders away from the point too much. 90% of what you play will be rubbish.”

Ideas of sin, death and rebirth proliferate on this poetic record that would prove to be Talk Talk’s farewell. With Miles Davis’ jazz fusion masterpiece In A Silent Way mentioned as a touchstone, this is an often skeletal album; graceful, bleak and unafraid of gaping chasms.

Myrrhman drifts in on near silence and amplifier hiss – this is a record that is in no rush to be heard – before the insistent Ascension Day, a wonderfully engineered piece from Brown that is driven by Lee Harris’ ticking drums, begins to take shape and clanging guitars grab us by the throat. Hollis’ lyrics seem more inscrutable than ever (“Double deal/ A season wrapt, too lax to lapse so soon”).

The nine-minute After The Flood drifts along on insistent drumming and an understated, yet throbbing bassline. Taphead is cut through by shivering, piercing horns and harmonica while ruminative closer Runeii leaves us bereft. An astonishing, if ultimately unknowable, record to bow out on.

Solo LPs

Herd of Instinct, ‘O’rang (1994)

The debut from Lee Harris and Paul Webb’s experimental outfit, pieced together from extensive improvisation. Includes Portishead’s Beth Gibbons as well as The The’s Matt Johnson.

Spoor EP, ‘O’rang (1994)

Harris flexes his muscles as a dance music percussionist and world music flavours are added. The exotic Charabanc D.I.P impresses.

Fields And Waves, ‘O’rang (1996)

More centred on the core duo of Webb and Harris, there’s a Krautrock feel to the motorik grooves of some of the material here on this 66-minute epic.

Mark Hollis, Mark Hollis (1998)

A spectral and haunting extension of his Talk Talk experimentalism, Hollis’ only solo LP was a jazz-infused triumph. Stripped-back and understated, it often showcased his belief in the power of silence.

Out Of Season, Beth Gibbons and Rustin Man (2002)

Webb and Gibbons collaborate again, this time on a full album under his Rustin Man moniker. Ostensibly dubbed ‘folktronica’, it’s influenced by Nina Simone, Billie Holiday and Nick Drake.

Drift Code, Rustin Man (2019)

Webb takes centre stage as vocalist on Rustin Man’s pastoral second album. His ‘Hollis-meets-Robert Wyatt’ voice is surprisingly affecting. Lee Harris occupies the drum stool.

Compilations

Natural History (1990)

Natural History (1990)

Compiled without the band’s permission, this sold more than one million copies. It remains the most obvious entry point for the uninitiated. However, due to its release date, the lack of Laughing Stock tracks renders this an incomplete picture…*

History Revisited (1991)

History Revisited (1991)

The straw that broke the camel’s back. Talk Talk sued EMI for releasing this remix album based on Natural History. There’s little of consequence here and the remixes offer nothing as revolutionary as the band they’re based on.

Asides Besides (1998)

Asides Besides (1998)

A curate’s egg of extended mixes, 12″ dub reboots plus some intriguing demos of Talk Talk, Mirror Man and Candy, where you can hear how Colin Thurston gave the tracks a pop sheen. The B-sides here add to the story nicely.

London 1986 (1999)

London 1986 (1999)

Unavailable but ripe for a reissue, this catches Talk Talk in a transitional phase. Recorded on 8 May 1986 at the Hammersmith Odeon, it was their last UK date as they toured The Colour Of Spring. A studio-only future lay ahead.

Live at Montreux 1986 (2008)

Live at Montreux 1986 (2008)

Released on DVD 22 years after the landmark concert itself, this captures the band during their one and only appearance at the fabled jazz festival with a finely-chosen setlist that takes in highlights from their first three albums.

The Very Best Of Talk Talk Reissue (2025)

The Very Best Of Talk Talk Reissue (2025)

Changes to the original release puts the band’s greatest hits in chronological order, with a new inclusion from their final album, Laughing Stock. The reissue will be available on black gatefold 2LP and CD on 14 March. Order the collection here

Sign up for the Classic Pop newsletter