The music producer Stephen Street is best known for his work with The Smiths, Morrissey and Blur. He tells an attentive Ben Wardle about the 10 albums he’s worked on that mean the most to him…

Even if you’re the sort of music fan who pays scant attention to production credits, the name Stephen Street will still be familiar. Maybe it’s the alliterative, almost poetic quality of his name, that ensures that it sticks firmly in the mind (and, yes, before you ask, it is the name he was given at birth – back in Hackney in 1960). More probably it’s because it’s very likely to appear on some of your most cherished records.

Beginning his career as a bass player (in ska-pop band BIM), he quickly became in-house studio engineer at Island Records, after which he went on to produce a list of albums that have sold in excess of 50 million copies.

To have worked with arguably the best British indie band of the 1980s would be considered enough justification by most producers to start preparing laurels to rest upon, but Street spent a large chunk of the 1990s working with perhaps the most significant British band of that decade too (no, not Oasis, Gallagher fans). And he has continued to surprise music lovers right up to the present day.

So in a career jam-packed full of classic albums, which 10 does Stephen Street pick to mark out his own life in vinyl?

(Rough Trade, 1986)

“To be honest, my favourite Smiths album is Strangeways, Here We Come, but I chose this because it’s my first album with a credit; Morrissey couldn’t quite bring himself to share the production credit! But it was a big breakthrough for me. The first step.

“It has aged well. At the time, I could tell it was a good piece of work, but it’s amazing how it’s taken on a life of its own, and it’s so revered. They were constantly on the road, so it was recorded a bit haphazardly. The Boy With The Thorn In His Side was done up in Manchester on their own, then I finished it off and mixed it in London; Bigmouth Strikes Again was recorded at RAK in London, but it was mainly done at Jacobs in Farnham.

“I always remember the afternoon I was working with Johnny Marr building up overdubs on There Is A Light That Never Goes Out. It was a wonderful, magical session where everything that we tried worked. He had this emulator and he was playing lines while I was chucking up delays on things. He had this flute line that was working, but it needed something on it to make it work a bit more. So I came up with this 3/16th delay thing, which made it float around and it enabled him to play a better part because he was reacting to what he could hear through the speakers…”

Read more: The complete guide to The Smiths

(Island, 1993)

“When Island played me the demos, I could tell Noel Hogan’s guitar playing was inspired by Johnny Marr. I went to see them at the Marquee and Dolores [O’Riordan] had no charisma on stage, she was singing sideways, away from the audience! But I thought it was interesting, it could be another Sundays or Cocteaus-type thing: interesting female vocal, nice layered guitars, just my bag!

“We did a week in Dublin and recorded Dreams. Dolores would only sing if her boyfriend was in the control room. I had to put my foot down, so I told her when it came to doing the vocals, it would be me letting her know if it was a good take… not her boyfriend! He did some really good yodelling vocals at the end of Dreams, but the rest of the band hated him. When you consider what the album went through after we finished, it’s a miracle it survived. Dreams came out in 1992 and flopped, so Island didn’t put out the album. They toured with Suede in America and Linger flopped, but someone on MTV’s Alternative Nation took a liking to the video and bit-by-bit Linger went bam! After Dolores passed away, I listened to it again and it still really sounds good.”

(HMV, 1988)

“In summer 1987, I sent a cassette to Morrissey saying, ‘Forgive me for being presumptuous, but here are some ideas!’ That was how Johnny used to work. He used to send a cassette to Morrissey with a finished backing track, hoping it would inspire him. So I sent this tape off and then I got married! I came back in August and there was a postcard from him saying, ‘I’ve decided I want to make a solo record with you, please send me more.’

“I knew I could cover the bass and rhythm guitar, but I needed a better guitarist to help, and that’s when I called in Vini Reilly. I’d worked with him on The Guitar And Other Machines. We already had Suedehead and I knew that was quite Smiths-like, but Vini’s style was so different to Johnny’s that I was intrigued to see what we could do in other ways. Morrissey came down and met Vini in my flat in Mortlake. He did a couple of guide vocals on my four-track demo and we booked The Wool Hall in Bath. I remember EMI coming down and saying, ‘Great. Carry on!’

“One thing I always picked up on working with The Smiths was that Morrissey often positions himself in relation to what the bassline is doing. So when I worked on Suedehead I made the bassline melodic, not just root notes. Everyday Is Like Sunday was me trying to be the bass player of Echo & The Bunnymen! The chords are quite simple, but again the bassline was a big part of the songwriting.

“We were finished by Christmas Eve, so the whole process from the postcard in August was really quick. Viva Hate was a magical session.”

Read more: The complete guide to Morrissey

(Factory, 1989)

“The reason I’m choosing this is because it’s very different to most things that I’ve worked on, but it is one of those records that I can put on and really enjoy for the mood it gives me.

“Halfway through Viva Hate, Vini threw a wobbler: he said he wrote everything, which was a complete fallacy. But we did this album just after and he didn’t want to upset me too much because the connection was good profile for him! I got a lovely letter from him after we finished, apologising for his mood swings and the things that he said.

“The idea for Vini Reilly preceded Moby’s idea of taking snippets from old records and rewriting them. There are no credits on the album anywhere – for example, there’s a track called Otis, which has an Otis Redding sample. The reason that we got away with it is because it didn’t sell very many copies!”

(Food/Parlophone, 1994)

“By summer 1993, we’d already made a start on what would be Parklife, and when Blur played the tent at Reading Festival, the vibe was electric, you could just tell there was something going on. So when we went into the studio we had a lot of bravado. But at that point, Andy Ross and Dave Balfe had to sign off on the demos so the record company could say, ‘Now you can go in and record those songs.’

“One day, Damon played me this very simple demo. I said, ‘That’s fun. It’s a disco song, let’s do it!’ It was just a bit of fun, 120bpm, drum machine… it came together really quickly in one afternoon. I remember getting a phone call from Andy Ross the next morning and I told him excitedly about this track, Girls And Boys, and he said, ‘Er, we haven’t asked you to do that one…’ They were really put out that we’d done it without them signing it off!”

(Food/Parlophone, 1997)

“The band were thoroughly sick of each other at this point. They’d been touring the world and Graham was hardly talking to Alex or Damon. Also, I didn’t know it at the time, but Damon was going through one of his druggier phases. I mean, I didn’t know Beetlebum was about heroin. I thought it was just something he’d made up!

“My first job as producer was to have a chat with Graham and see if I could talk him round. There was a conscious decision to move on from that trilogy of Modern Life Is Rubbish to The Great Escape; they didn’t want brass sections or strings, the record was going to be much more primal. Interestingly, when a band decides to do something different, the first thing that usually gets changed is the producer, but they’d decided to stay with me, thank God!

“I had just bought this new recording equipment called RADAR, which enabled me to edit things really quickly. There were two drumkits in the room, Graham was on one and Damon was on the other and they were jamming. I just recorded a little bit and looped it. That’s how Song 2 came about; it was built up in the afternoon over that groove.

“Every Blur album’s got a throwaway punk song on it, like Bank Holiday or Advert, this was originally just going to be that. Damon couldn’t think of anything else to sing instead of ‘Woo-hoo!’, but straight away everyone in the room thought, hang on, that’s universal. Damon tried later on to come up with more meaningful lyrics, but he couldn’t find anything with the same energy and vibe the guide vocal had. I reckon about 60% of the vocal on that track is guide vocal.”

Read more: Blur – Album By Album

(Transcopic/EMI, 2004)

“When Blur were promoting 13, the album they did with William Orbit, Graham said a couple of things in interviews that were a little bit hurtful to me. He could be quite spiteful sometimes, especially when he was in his drinking phase. So when I got this phone call from his management saying he’d like to meet me to talk about producing his next album I was quite surprised. I hadn’t seen him for years.

“This was his fifth solo album. I went to see him play and saw him afterwards. He apologised and said he didn’t mean to say those things and that he did really want me to produce his record.

“As soon as we got in the studio, we hit the ground running. He was a one-man band; he played absolutely everything. He also worked really hard on his singing and his melodies. We all know he’s a brilliant musician, but vocally he sometimes doubts himself, so I was trying to encourage him to be more confident as a frontperson. Bittersweet Bundle Of Misery is a good example of that.

“When we were doing Freakin’ Out, I said to him, ‘Can you drop the drums out and carry on playing that riff?’ Straight away we both went, ‘The Skids!’ When the drums were going through all the time we didn’t notice it, but as soon as we took them out it was Into The Valley!”

(B-Unique, 2005)

“Working with Kaiser Chiefs, I was able to bring to bear all the knowledge I’d got from working with The Smiths and Blur. I’d been working with Ordinary Boys, and at one of their shows the support band was Kaiser Chiefs. I’d got there too late to see them, but after the show Nick Hodgson from the band introduced himself, said they’d like to work with me and gave me a CD with Oh My God and I Predict A Riot. I thought it was interesting, but at that point everything Ricky sang, Nick sang, too; it was two people singing the same part.

“Mark from B-Unique phoned me and asked me whether I’d do a test session. Before the session, I told them I didn’t like the Beach Boys-type layered vocals – I wanted to have more of a lead vocal with some character. Nick said, ‘Well, there is no lead singer in the band.’ I put my foot down and I won that battle because they wanted to work with me.

“We did the session and recorded I Predict A Riot and it was great. So then we did Everyday I Love You Less And Less and Oh My God – the first three songs I recorded with them were all smash hits. But I was working with New Order on Waiting For The Sirens’ Call and it was taking months, so I waved goodbye to half of the album.”

The Courteeners – St. Jude

(Polydor, 2008)

“It was a real buzz doing this record. I saw them live in Manchester and it was nearly like watching The Smiths in terms of that religious celebration. It was an electric gig and I was really impressed with Liam Fray’s lyrics.

“We had a great chemistry in the studio and put the record together pretty quickly. When it came out, the press were really dismissive, but What Took You So Long? and Not Nineteen Forever have gone on to be anthems – people absolutely love them.

“I love Yesterday, Today & Probably Tomorrow. I remember saying to Liam, ‘Let’s try and do it acoustically like The Jam’s English Rose.’ I found the sound of a Manchester railway station online and it sat in the track at just the right point.”

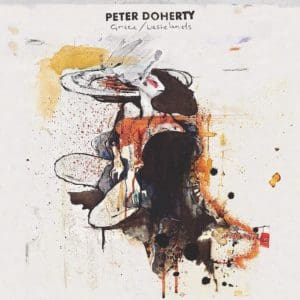

(Parlophone, 2009)

“I regard Peter as a true poet. Underneath the horrible fug of drug addiction he’s a really lovely person. People like him get surrounded by vampires, and I felt quite protective of Peter when I was working with him. I was trying to be one person supplying good rather than bad. Whether he wants that depends on what state he’s in.

“The only demos I got before were him mumbling away into a microphone on his laptop. I knew he was a big fan of Graham Coxon, and Graham was a big fan of The Libertines, so I came up with this idea. But I said to him, ‘You can’t let me down because I’m not going to get Graham in and upset him.’ We did a very quick session at my place with them playing together, I think we did Arcady.

“On the demo of Last Of The English Roses there was this rustling sound. God knows what it was, but it was quite hypnotic, so I sampled it and suddenly the track took on this slightly dubby, trip-hoppy feel. Then Drew [McConnell], the bass player from Babyshambles, came in and suddenly it turned into this reggae-fied track.

“Looking back now at what we started off with and how it ended up, it was like we were blessed because it seemed that everything I tried, to keep the ball rolling, worked. When Pete went off to do live dates, I suggested doing it as a proper band with me as musical director, Graham on guitar, Drew on bass. But then Blur reformed, so the only thing to do was for me to learn my chops, practise guitar and see if I could fill in. So there I am, at the age of 50, on stage playing guitar at Glastonbury! All those years of being a producer and there I was on stage again. It was like full circle.”

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.