Gary Numan Interview: ‘It’d be arrogant not to do the nostalgia thing once in a while’

By John Earls | November 20, 2019

It’s been 40 years since Gary Numan dissolved Tubeway Army and immediately had solo success with Cars. It’s just as significant that it’s 25 years since the electronic music innovator rescued his career from total disaster. Classic Pop conducted a Gary Numan interview about how he’s avoided selling out, his battles with depression and the difficulties of making new music when the kids are home…

Gary Numan happened to wake up early one morning recently. Unable to get back to sleep, at 5.30am he began going through some contracts: Gary has managed his own career for four years. Two hours later, his wife Gemma was woken up by the sound of her husband laughing to himself. “What are you giggling at?” she asked. “In the last two hours, I’ve sorted 10 things about contracts, tours, a film offer – and I’ve not got out of bed,” Gary told her. “This is what my life is like. Isn’t it brilliant!”

To some people, Gary Numan will always be the stern, distant replicant he appeared to be at the start of his career. His lifelong love of science-fiction fed into the black-clad warrior intoning Are ‘Friends’ Electric? and Cars as if Kraftwerk were a bit too chirpy, actually. The music has remained ominous – there’s a reason Marilyn Manson and Nine Inch Nails leader Trent Reznor are devotees – but the Gary Numan of 2019 is able to celebrate the fact he’s spent the past 40 years being singularly, determinedly, totally himself. He’s also bloody funny. Hardcore fans already know that: you could tell at the “An Evening With” interview events around most recent album Savage in 2017 that Gary is a big Ricky Gervais fan.

He can afford to joke about his career, not least that refusal to sell his soul. “The fans mean everything,” he says. “I can be as arrogantly focused about only doing what I want and talk until the cows come home that I won’t do nostalgia tours but if nobody comes to see me and the records don’t sell, it’d all be for nothing. I’d just be someone talking in a little room to myself with nobody interested.”

Savage (Songs From A Broken World) reached No.2 in the UK albums chart, only denied the top spot by Foo Fighters’ Concrete And Gold, and was Gary’s first Top 10 LP since I, Assassin reached No.8 way back in 1982. It must make Numan feel like he’s riding the crest of a wave now that he’s started a new album?

Savage (Songs From A Broken World) reached No.2 in the UK albums chart, only denied the top spot by Foo Fighters’ Concrete And Gold, and was Gary’s first Top 10 LP since I, Assassin reached No.8 way back in 1982. It must make Numan feel like he’s riding the crest of a wave now that he’s started a new album?

“Waves are fragile things,” he chuckles. “I’ve ridden waves before, and I’ve crashed them spectacularly. The fact that Savage was successful doesn’t make me feel buoyant about what I do next, it’s just extra pressure. I have to raise the bar again. What if the next album only gets to No.5? If you’d asked me before 2017 how I’d feel about a No.5 album, I’d have jumped up and down and thought it was the best thing ever. Now, it’d feel like a step back after a No.2 album. If you’re a glass-half-empty person – which, yes, I am! – success only makes the next record harder.”

The morning Gary speaks to Classic Pop from his home studio in Los Angeles, he does allow himself to feel happy about that pressure: he’d finally nailed the chorus of new song Intruder the night before. “I’ve been on that chorus for the best part of a month,” he frets. “For me, that’s pathetic. But it’s the first important song of this new album, and it had to be perfect.”

It’s not so unusual for Gary to finesse a song – Here In The Black on 2013’s Splinter (Songs From A Broken Mind) took him 32 versions. “And the one we went with was the first one we did.” For Gary, there are various reasons for this perfectionist streak. “I’ve a mixture of drive and the desire for perfection, coupled with a staggering lack of self-confidence,” he explains. “When I write a song, I feel, ‘I must be able to make this better, because I’m not great.’” There are pluses to this attitude – Gary would rather realise a song could be improved than be someone who “thinks they’re a fucking genius and throws a song out there because they think, ‘That’s a great song because I wrote it.’”

However, such constant self-doubt can become destructive. “One of the downsides of essentially working alone is getting into a downward spiral,” he says. “Doubting everything I do is very easy. There are many songs I’ve written where I’ve thought, ‘That’s brilliant!’ when I’ve written it. But an hour later, I’ll think, ‘I don’t like that lyric’ and three hours after that I’ll think it’s the worst thing ever. It’s a real danger. Many years ago, I erased everything I’d done in the previous two years. Not everything I did in that time could have been rubbish, but I was crushed by this feeling that nothing I did seemed good enough. Now, I’m better at talking myself out of it.”

Have any of Gary’s songs emerged fully-formed and he hasn’t doubted them? “I end up going back to the original idea a lot,” he ponders. “Actually, the quickest song I ever wrote was Cars.” That’ll be worldwide No.1 classic Cars? “That took 10 minutes. It’s such a simple song – it’s just one little riff and a big descending keyboard line over the top of it. It doesn’t even have a chorus! If Cars had taken more than 10 minutes to write, I should have been ashamed of myself.”

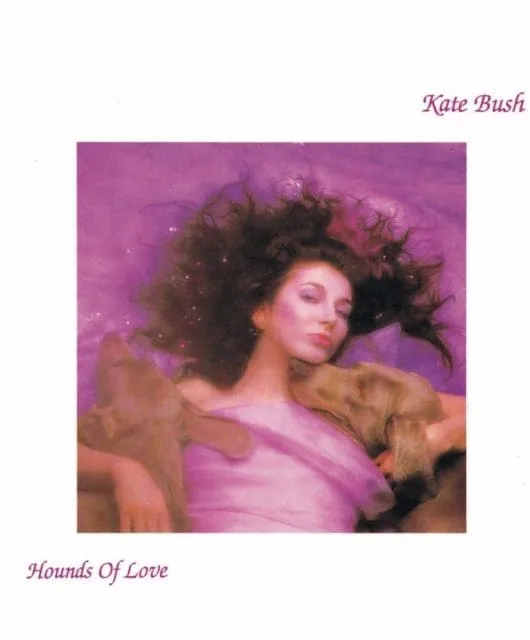

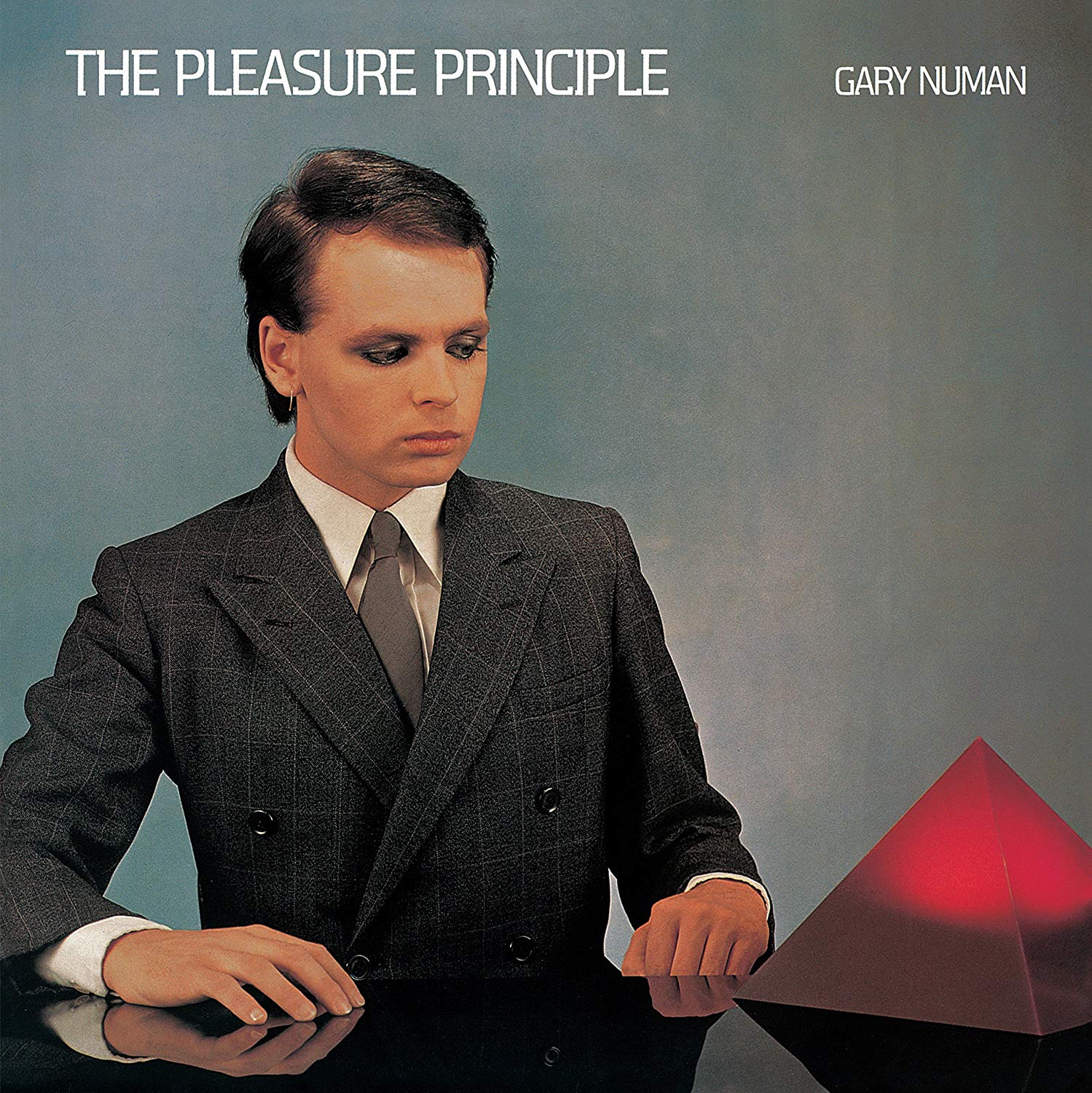

Don’t be fooled into thinking Gary Numan is dismissive of his past. He’s not, and his new tour (R)evolution celebrates 40 years since debut solo album The Pleasure Principle. As well as Cars, that album featured Metal, cited by Afrika Bambaataa as an early influence on hip-hop, and M.E., which became the basis of Basement Jaxx’s classic Where’s Your Head At. Gary is quick to point out his tour celebrates 40 years of playing live rather than comprising songs of his early solo era. But he rates The Pleasure Principle. Sort of.

“When I toured the album on its anniversary 10 years ago, I was pleased to see how unusual its song structures are,” he says. “I hadn’t realised until then how different those songs are to what else was around at the time. That was a pleasant surprise.”

The Pleasure Principle was released just six months after Tubeway Army split, but that wasn’t exactly a big deal for Gary. Formed on the punk scene in 1976 and quickly signed to Beggars, Gary wanted out as soon as he visited the band’s first studio and saw a synthesiser for the first time.

“Tubeway Army was only ever a vehicle for me to get somewhere else,” he states. “I was only ever in a band because everyone else was in a band. As soon as I found synthesisers and started making electronic music, I told Beggars I didn’t want to be called Tubeway Army anymore.” He pauses, aware of how dismissive he sounds towards his former bandmates. “I was acting as if the band was just me,” he admits. “That’s pretty fucking arrogant! But that shows where my head was at: it’s horrible, but it was all about me and where I was going.” Frankly, it’s a miracle Tubeway Army lasted for two albums. “My attitude was: ‘You’re my mates. If you want to grab on and come with me, great. But don’t misunderstand me: this is about where I’m going musically.’ I’d seen punk was finished and I thought the name ‘Tubeway Army’ overshadowed the new music.”

Tubeway Army hadn’t even toured, with Gary’s first full live shows happening around The Pleasure Principle. It was a distressing experience. The press thought that, like these other synthesised upstarts, Gary Numan was a talentless wrecker of real music. Having Asperger’s Syndrome means Gary doesn’t like making eye-contact with strangers, so being in front of thousands of people felt upsetting.

“It was all a bit horrible,” he says sadly. “I didn’t take to touring well at all. I felt really vulnerable and the press were just horrible. I’d thought touring was going to be exciting, glamorous, fun. It is now, but I had to learn how not to be so frightened, to not care so much about what other people said. There were shows I enjoyed – loads of kids turning up because they like what you do is the good bit! But the overall theme of that tour was to be nervous, anxious and often disappointed.”

In 1981, after a fraught arena tour for his chart-topping Telekon album, Gary announced that he was quitting touring. Asked if any of his 80s peers were supportive, he says: “I remember getting slagged off by a lot of bands, but I don’t remember too many being supportive. Maybe I’m being unfair and there might have been, but I don’t remember it. I’m not bitter about that, it was just different back then.”

He returned to performing 18 months later but, by then, Gary’s imperial commercial phase was ebbing away. The rebirth wouldn’t happen until his album Sacrifice in 1994 marked the start of full-on, heavy, uncompromising electronic music. Sacrifice was made at the lowest point possible.

“I thought I was finished,” he admits. “I had no record deal and I was a pariah. The gigs were virtually unworkable, as so few people were turning up. Gigs weren’t a joy, they were an embarrassment. My previous album Machine + Soul was the worst thing I’ve ever done, as I had no ideas. There were so many difficulties in my life that I had nothing to say. I was absolutely broke and my house was about to be repossessed. There was no point trying to win the fans back or win record company A&Rs over – I’d tried that – so I treated making music just as a hobby again. I was back to being a teenager, thinking, ‘My music can be as dark and as heavy as I like, as nobody’s going to play it anyway.’ And that resulted in my best album for years. There’s a road from Sacrifice to the music I make now.”

Asked if the 25th anniversary of Sacrifice is as significant to Gary as 40 years of touring, there’s a rare pause. He’s a dream interviewee – funny, thoughtful, polite, eloquent. But Gary hadn’t realised until Classic Pop brings it up that he’s been back on the right path for so long.

“Is it 25 years?” he boggles. A delighted laugh travels joyfully down the phone from LA. “Fuck! Woah! It feels like Sacrifice was six years ago, but most of my career has come since then. Wow! I’ve never actually thought that through, that the bulk of my career has been making heavy electronic music with an ‘I don’t give a fuck’ attitude. Ha!” There are few experiences in life for childlike wonder than making Gary Numan’s day.

That uncompromising attitude is something Gary partly ascribes to having Asperger’s Syndrome. “I’m not saying having Asperger’s is easy, and I’m aware of people with it who have more difficulties than I do,” he says of the condition. “But I wouldn’t change it for a second. Coping with it is a different experience depending on who you’re with. I’m lucky to have an amazing wife who helps me enormously with Asperger’s.”

Gary finds social situations difficult, explaining: “I’m not particularly good with that, and Gemma guides me through it. I see the world in a slightly different way – I react differently to the norm. The fact that I react differently sometimes causes upset to people around me, as I don’t react to emotional things in the way you’d expect. I feel them just the same, but I don’t react the same. That’s a small price to pay for the benefit Asperger’s brings. It enables me to do this. I can say, ‘I don’t give a fuck, I just do what I want to do.’ I can shut out any problems and compartmentalise things into little boxes.”

It’s a worldview which extends to Gary’s attitude to those early breakthrough years. He has toured his past albums before, but it’s rare. “It’d be arrogant not to do the nostalgia thing once in a while,” he says. “It keeps the people happy who love the early stuff. I understand why they love it, and thankfully a lot of them are still with me and my current music. At times, it’s felt like I was stretching my arm, dragging the fans along with me a bit. But at other times, and especially recently, it hasn’t felt like that at all. I’m sure I’ve got fans who love Savage who, a few years ago, would have said, ‘I wish he’d do a new album that sounds like Telekon again.’ But it’s got to the stage where I’ve got the freedom to put the setlist together I want, rather than strategically having to place certain songs in the set to keep the momentum going.”

Even at the low ebb before Sacrifice, Gary resisted the temptation to remake the early hits. And there were plenty of offers… “There were a few moments along the way where I wobbled,” he laughs. “But generally, I’m really proud I’ve taken the long view of my career. People have said, ‘Do a duet on Cars with me and I’ll give you £20,000’ and I think, ‘Fuck me, that’d be the kiss of death.’ It’d come back to haunt me and undo everything I’ve been trying to achieve. If I’d done Are ‘Friends’ Electric? 1998 Remix or whatever, I wouldn’t have made Splinter or Savage. Maybe I’d be sat here looking forward to the next Here & Now-style nostalgia tour, where I’d be singing Cars, Are ‘Friends’ Electric? and one new song nobody wants to hear. The only time I do nostalgia is when I feel the fans are due, but I feel nervous and uncomfortable doing it.”

Gary intends releasing his new album – provisionally also called Intruder – in September 2020. It continues the ecological themes explored on Splinter and Savage, as Numan reveals: “The song Intruder is as if Earth is talking. If it could speak, what would it say? Would it be seriously angry with what’s going on? Would it see us as a misguided ally or as a virus on its surface? That’s the thrust of the whole record, though there’s a lot more thrust to come. Or I hope so, as it’ll be really hard to write 15 songs about one thing! I like heavier electronic music with big choruses, so I know the album will be that sort of music.”

Having sung about climate change over his past couple of albums, Gary is unsurprisingly no fan of Donald Trump. “Trump is systematically undoing every environmental protection Obama put in place, for absolutely no gain I can see other than out of spite to attack Obama. On a purely economic level, the amount of jobs and research available from tackling climate change would benefit industry. Trump is an idiot, but the rest of the world isn’t doing what it should either. Every time I read the latest scientific report, it’s worse: things are going to happen sooner rather than later, it’s getting faster… People say, ‘It’s a natural cycle.’ Is it fuck! I don’t see why anyone doesn’t listen to what scientists are saying or just look out of the window to see how clearly messed up the climate is.”

Gary needs to finish making Intruder by the end of April in order to be released next September. With touring commitments, he won’t be ready to really get into it until November. And then there’s the family to consider. Gary and Gemma have three daughters aged 12-16. On the day of our interview, Raven, Persia and Echo have friends over and are mucking about in the family swimming pool. “I try very hard to put work and home life together like an intricate jigsaw,” says Gary.

“When I’m not touring, I don’t want them to notice I’m working at all. When I’m home, I try to drop the kids off at school at 8am, then come home and be in the studio until around 4pm so that, when they come home, I can always be around.”

Thankfully, Gary has been able to train his creativity to work during school hours. “When the kids first came along, I wasn’t used to it,” he laughs. “It’d take me half a day just to tune the world out and tune into any creative ideas. But there isn’t the time for that. I realise that’s the way it is now. I’m on it pretty much as soon as I sit down.” Gary Numan has been mostly on it for 40 years. As long as the planet will let him, he’ll keep pushing forward.

*contains affiliate links