Patience Is A Virtue: James Jackman Interview

By John Earls | January 2, 2020

George Michael’s working methods have always been a source of mystery. Just how much music did he make in addition to his five solo albums? How much of it will we get to hear after his passing? How did the star’s close-knit team earn his trust? And did he secretly get Daft Punk to produce one of his singles? George’s team rarely talk publicly, but James Jackman – the star’s co-writer and co-producer since 1997 – gives Classic Pop the first in-depth insight into the icon’s later career…

The exact amount of music George Michael made has been a constant source of speculation. After Wham! split in 1986, George made five albums including covers set Songs From The Last Century before his death aged just 53 in 2016. When the soundtrack album to festive romcom Last Christmas was released earlier this month, it offered the first taste of the music the star had been working on. This Is How (We Want You To Get High) is classic George Michael – a social commentary song that, despite its hard-hitting message about drug and alcohol abuse, is an absolute banger.

This Is How (We Want You To Get High) was co-written and co-produced by George with James Jackman. James isn’t a high-profile name – but he was a key part of George Michael’s career for the last 19 years of his life. He co-wrote more songs with George than anyone since Andrew Ridgeley and knows better than anyone the care George took in the studio to get his songs just right.

“The album George was making when he passed would definitely have been a return to form,” says James. “It was an upbeat album, a 21st century Faith. George was excited by it, as was everyone who worked with him on it.”

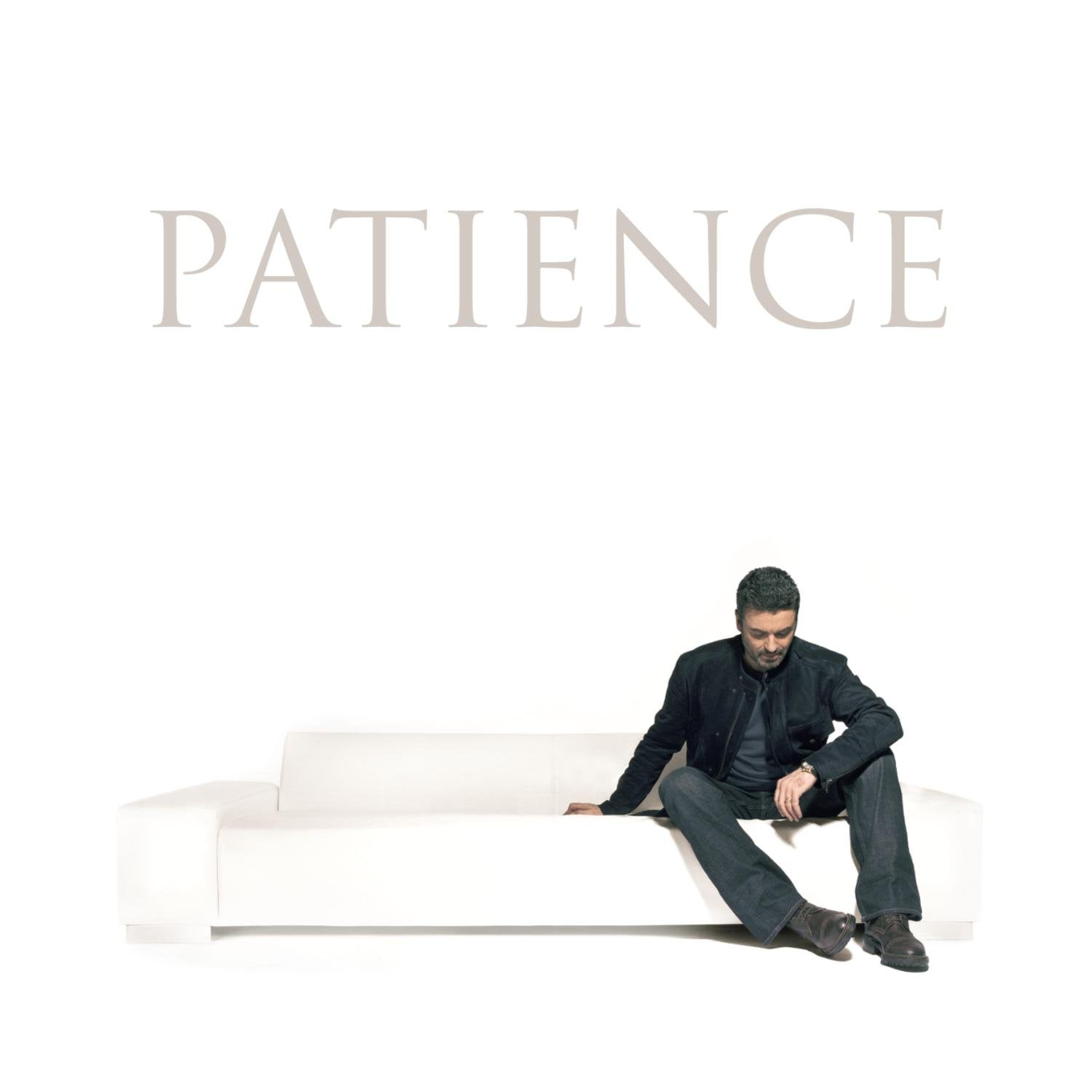

Since Patience in 2004, George had thrown himself back into touring. Having become freaked out by the intense touring demands of Faith, George lost his love of live work for some years. But celebrating a quarter of a century in music led to his wild 25Live tour, before the sumptuous orchestral shows of the Symphonica concerts. “After he completed 25Live and Symphonica, George wanted and knew he needed to come back with an album,” James explains. “He wanted it to be positive. Around Older and Patience, there was a lot of loss in George’s life.

“They’re moving, personal albums and George was ready to come back with something brighter. The media love knocking big stars down – but they also love a comeback kid, and George was like Lazarus.”

However, fans shouldn’t expect a sudden glut of posthumous material to be released. George completed four songs for his final album, including This Is How (We Want You To Get High). “A number of songs were worked on and developed,” James reveals. “But they weren’t completed. You’d have a verse and half a chorus of a song, or a guide vocal over a completed track which doesn’t have any backing vocals. George was such a perfectionist and had control over his music, it’d be disrespectful to start trying to finish songs for him.”

Posthumous Releases

George’s catalogue is controlled by his estate – in essence, his manager and lifelong friend David Austin, George’s sisters Mel and Yioda, and his father Jack. “With a lot of artists, people posthumously put out all sorts of demos and you think, ‘Why have you done that?’” admits James. “George’s family don’t want to suddenly pull out loads of demos from the vault. They only want songs George felt comfortable with. That applies to songs from George’s old album sessions, too. How the other three songs George finished will come out and on what projects, I don’t know.”

There could potentially be some remixes of existing tracks, though it’s hard to improve on George’s originals. James recalls Mark Ronson being asked to remix Freedom! ’90 for the 25th anniversary of Listen Without Prejudice Vol 1 only to tell George: “I can’t do it – it’d be like reworking the Mona Lisa.”

Emma Thompson wrote, produced and stars in Last Christmas and is one of the lucky few to have heard all four completed songs. “Emma was apparently dancing around her kitchen to it all,” laughs James. “The film was keen to use the music, but the estate didn’t want to throw all the unreleased songs into one movie. Emma chose This Is How… as it resonates with the film’s themes and wrote it into the final scene.”

The genesis of This Is How… was a backing track James gave to George in 2012. “George phoned me one evening, really excited and said, ‘I’ve got the most amazing hook over your track,’” James recalls. “He said, ‘I can really hear this working’ and played it down the phone. It was classic George Michael, very immediate.”

Despite George’s patient working methods, once he got inspired songs often came together quickly. “For George, it was always about the lyrical idea,” says James. “Once he had a lyric idea, he’d usually finish the main demo pretty quickly. We’d work flat out to develop it and complete the song.

“This Is How… is a social comment song, but it’s not autobiographical. It’s got George’s trademark humour and self-deprecation.”

Socially Conscious

Socially Conscious

Although George wrote all his own lyrics, he’d often discuss ideas for songs with co-writers like James, David Austin, Johnny Douglas, Ruadhri Cushnan and his long-term engineer Niall Flynn. “When George was struggling for ideas, we’d debate a lot,” says James. “George was a very bright man who was socially conscious, very aware of the world and his surroundings. Ideas that we’d spoken about over the years would spark something in him. He liked a debate.”

Of course, not every song idea would get used. “You had to be thick-skinned,” James admits. “George would often sketch an idea, leave for the day so you’d add some ideas to his, but he’d come in the next day and disregard the lot. It was often a slow process – you’d turn out ideas, work on them for weeks and those ideas would be shelved. I was able to be honest with George. He didn’t want to be surrounded by sycophants. George had to feel comfortable with you, because if you’re working 70 hours a week with someone, he has to trust you creatively and technically. There were times when I had production input on a track that went to radio and George would go, ‘I told you that part should have been like this, not like that! I should never have listened to you!’ But he took the rough with the smooth and he had a very trusted group – the same with his session musicians.”

Once James Jackman earned George’s trust, the pair became good friends. “George was a very private person,” says James. “Once he established a relationship, it was worth a lot to him. George was pretty much a kid when he got successful, he had to be guarded. So you need friends you can have a laugh with behind closed doors and know they’ll be discreet. George had a wicked sense of humour. He was able to laugh at himself.”

George befriended James when he signed James’ band Trigger to his record label Aegean in 1996. A trip-hop/drum & bass crossover trio in the vein of Morcheeba, Olive and Massive Attack, George featured on their debut single Chameleon. “We were Pete Tong’s Record Of The Week and Jo Whiley liked us, we were having our moment,” recalls James. Tragedy struck when fellow keyboardist Jim Thomas died of leukaemia while finishing their album. Smoke And Mirrors was released in 1997, but James and singer Arianne Schrieber decided not to carry on without Jim.

Hanging On The Telephone

For the next 19 years, James saw more of George than anyone apart from his wife and two children. “If you worked with George, it was like being a doctor on call,” smiles James. “Before we had our kids, I was in Cornwall with my wife when I had a call from George going, ‘Where are you? Can you come back to work? I’ve got an idea.’ Or George’s manager would phone on day two of a five-day break. But you knew that was George. If he had that moment, you’d be there. There were periods of weeks and weeks without a day off.”

The most extreme moment of duty came in the run-up to Patience. George had a studio built at his home in Goring, in rural Oxfordshire. The studio was built by the team at George’s favourite recording base, Sarm East. “The house was next to a weir, so it was built to be completely sealed from any water rising up,” James explains. “But they didn’t think water would come through the front door and down a flight of stars into the studio. I got a phone call between Christmas and New Year from George’s manager – ‘The studio’s flooded! You need to get here now!’ By the time I got there, a torrent of water was lapping against the faders. The insurance loss adjuster came down and just went white.” The damage cost £500,000 but, more importantly to George, no insurer would touch the idea of George trying to rebuild the studio.

“George had been comfortable working from home,” says James. “Working at commercial studios was costly for him. He’d book a studio out but, if he wasn’t feeling it, he wouldn’t turn up for five days. But he never counted up the money, it was always about the music.”

Seeing George at work was worth the disruption to normal life. Easygoing and funny, it’s easy to imagine James being a calm presence in the studio. “It was like any job,” says James Jackman. “For 95-98% of the time, it was exceedingly dull. You’re there scratching your arse while George is thinking, or spending hours trying to find the right hi-hat sound. We had cameras set up in the studio for a time, maybe as archiving for documentaries. But David and George looked back at the footage and it was just so dull! It was worth it for those 3-5% moments of inspiration, because the hairs would stand up on the back of your neck.

“When This Is How… came together after the initial sketchy idea, it was wonderful. First hearing George’s vocal on John And Elvis Are Dead was just brilliant. When a song came together, it was incredible to be around, because you were watching one of the greatest singer-songwriters this country has ever produced at the top of his game. That was magical to be a part of.”

“When This Is How… came together after the initial sketchy idea, it was wonderful. First hearing George’s vocal on John And Elvis Are Dead was just brilliant. When a song came together, it was incredible to be around, because you were watching one of the greatest singer-songwriters this country has ever produced at the top of his game. That was magical to be a part of.”

One of James’ first co-writes with George isn’t officially credited to him. The story of 2002 hit Freeek! is bound up with Daft Punk. George had been invited to work with the duo on what became their 2005 album Human After All.

“Daft Punk sent a catalogue of demos for George to potentially write around,” James recalls. “Those are in George’s archives. He went to Paris for a couple of weeks for some sessions. When he came back, I said, ‘How did it go?’ and George went, ‘Yeeeah… I sat on a beanbag in Guy-Manuel’s flat eating M&Ms.’”

George ultimately didn’t feel he could contribute to those demos. “When Daft Punk’s album came out, George said when he heard Robot Rock, ‘Oh, that’s one of the demos they gave to me!’” He remained a fan, and Freeek! was inspired by the experience. It’s officially credited as being co-written and co-produced by The Moogymen – an alias that’s gone down in George Michael folklore. “Freeek! was such a departure for George that we wanted some intrigue about it,” says James. “We thought, ‘Let’s be quirky about this one’. It was brilliant when fans started speculating that The Moogymen was an alias for Daft Punk! Really, though, The Moogymen were me, Niall Flynn and Ruadhri Cushnan.”

George’s love of Daft Punk was typical of his eclectic taste. James points to George’s cover of This Mortal Coil’s Song To The Siren on the B-side of White Light and his cover in Manchester of Ian Brown’s F.E.A.R. on the Symphonica tour as examples of the singer’s love of the offbeat. He was also a huge Massive Attack and Tricky fan. It was George’s admiration of Kanye West which led to him experimenting with treating his voice. Using an Auto-Tune-style box called TC Helicon Voicelive 2, George experimented with his vocals from his 2012 cover of New Order’s True Faith onwards – it’s there in This Is How (We Want You To Get High), too.

George was aware of the controversy of such a gifted singer using the effect. “A lot of people reacted by saying, ‘It’s sacrilege, you can’t use that on George Michael’s voice!’” James recalls. “But why couldn’t he? People felt George’s voice was too hallowed to experiment with, but he was being creative. George felt very frustrated that people wouldn’t accept him branching out. When he covered True Faith, I did try to steer him, saying, ‘It works incredibly well, but perhaps you could use your natural voice in the chorus?’ But George was adamant he wanted the whole song like that and some people loved his True Faith. It disappointed him that people couldn’t see he wanted to be more experimental. It would have been so much easier for George to knock out ballads, but he wanted to stretch himself artistically. On his final album, he experimented with his voice on other songs, but there would have been a lot of pure George vocals, too.”

George was aware of the controversy of such a gifted singer using the effect. “A lot of people reacted by saying, ‘It’s sacrilege, you can’t use that on George Michael’s voice!’” James recalls. “But why couldn’t he? People felt George’s voice was too hallowed to experiment with, but he was being creative. George felt very frustrated that people wouldn’t accept him branching out. When he covered True Faith, I did try to steer him, saying, ‘It works incredibly well, but perhaps you could use your natural voice in the chorus?’ But George was adamant he wanted the whole song like that and some people loved his True Faith. It disappointed him that people couldn’t see he wanted to be more experimental. It would have been so much easier for George to knock out ballads, but he wanted to stretch himself artistically. On his final album, he experimented with his voice on other songs, but there would have been a lot of pure George vocals, too.”

Talking to James, it’s clear he’s itching for people to hear those other finished songs. But, after George’s passing, it will be a bittersweet experience. “We became very close friends,” says James. “George left a big hole in my life professionally and personally. It’s difficult to hear his music. But we’re blessed by the musical legacy George left behind. It’s fantastic to hear the unreleased music getting out there and I think George would have been pleased and humbled by the outpouring of love he’s had posthumously.”

White Heat Of Creativity

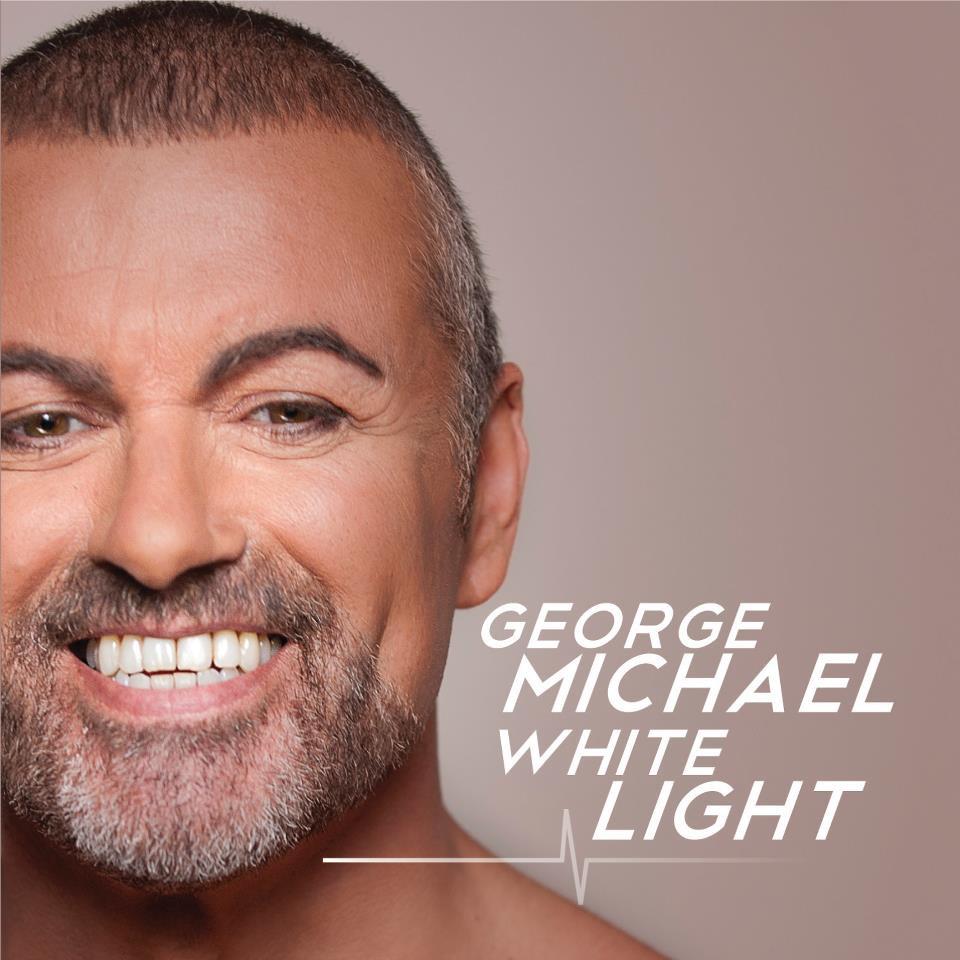

One of the many tragedies of George’s passing is just how positive the singer seemed to be in his life and music when he died so suddenly of heart failure. One of the songs James created with George was White Light, the 2012 single which seems to have kickstarted his final burst of creativity. It was written after George recovered from pneumonia, having been taken ill in Austria at the end of the Symphonica tour. “George became very ill very quickly,” James remembers.

“I think it was from the stresses and strains of touring. It was a real close shave and it was the white light – George felt he’d seen it.

“I think it was from the stresses and strains of touring. It was a real close shave and it was the white light – George felt he’d seen it.

“He’d had a nadir in his life, but White Light was, ‘I’m through, I’ve come back.’ White Light is a better record than it’s given credit for. If there’d been an album around it, it would have been easier to promote.

“It was disappointing to George it didn’t have the success he’d hoped, as it’s such a cool-sounding record.

“George was the whole package,” says James. “He was a great singer, writer, arranger, producer, he knew how his music should come out and he had the looks. His records will be remembered and covered in 50 years’ time.

“How many other performers tick all those boxes? I was blessed to be able to work with him.”

Click here to read more interviews