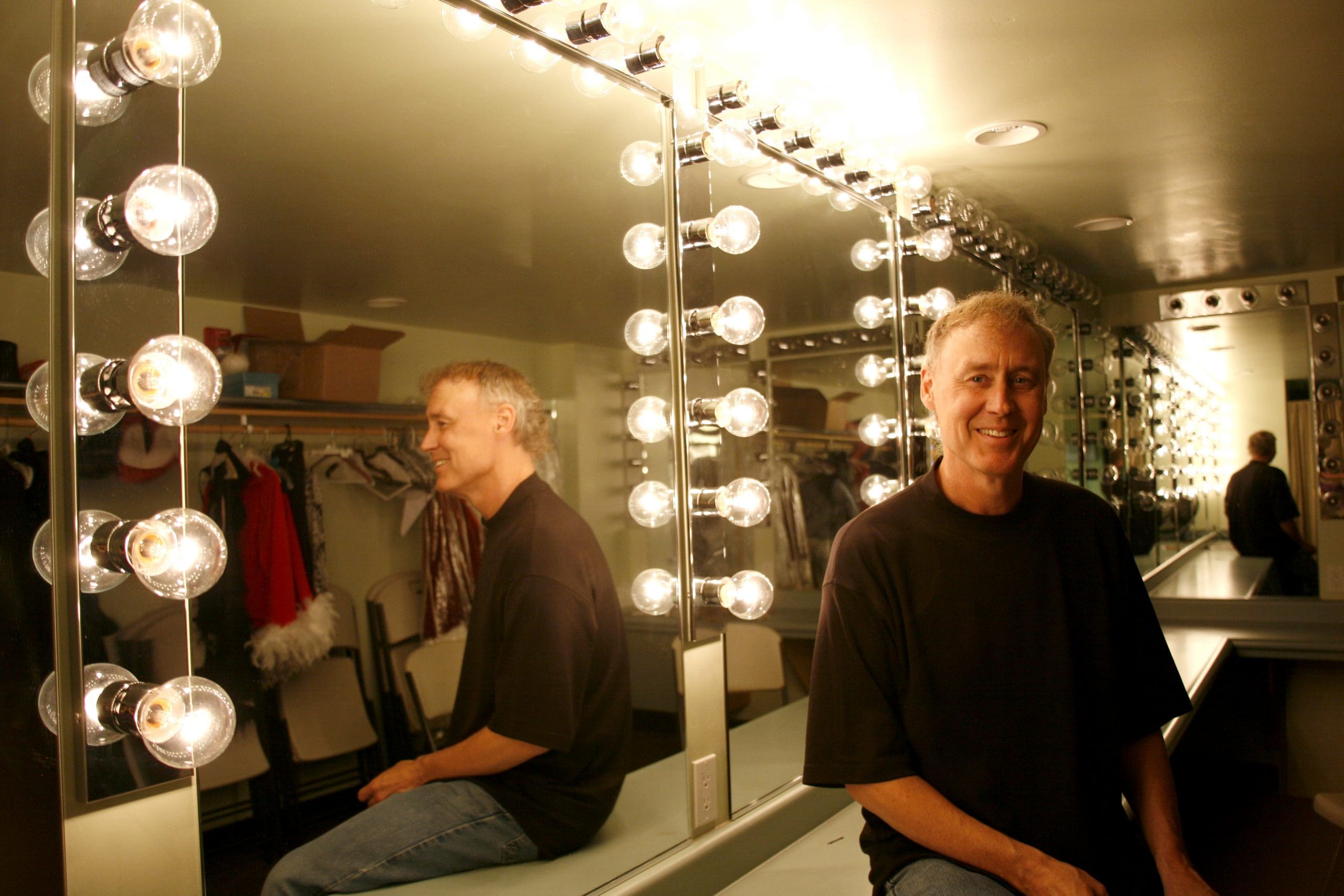

Picture credit: Sarah Walor

As Bruce Hornsby returns to the UK on a wave of renewed acclaim, the piano man tells Douglas McPherson about his constant quest to evolve and how he has a hard time listening to his early hits…

Bruce Hornsby is having a moment right now. A mere 33 years after he came to fame with the unforgettable piano-led social conscience-pricking ballad The Way It Is, the Virginian singer-songwriter has been receiving some of his best-ever reviews for his latest album, Absolute Zero.

In particular, Hornsby has acquired a new cachet with the hipsters, thanks to his association with Justin Vernon, aka the Grammy-winning Bon Iver.

Vernon initially displayed his fondness for Bruce’s music on Beth/Rest, an unmistakable homage to the Hornsby sound that he described as the track he was most proud of on Bon Iver’s self-titled second album. On Absolute Zero he teamed up with his idol to co-write and sing on current single Cast-Off.

Hornsby first became aware of Vernon via Google Alerts. “In 2011 or 2012 I started getting these alerts about Bon Iver and Justin Vernon. He was shouting my name out as someone who’d influenced him as a young musician. I started investigating and the first Bon Iver song I heard was Holocene. I just loved it. I thought it was gorgeous, interesting and unique-sounding.

“It was an instant ‘yes’ from me,” Hornsby continues. “I was doing a solo piano tour that ran through the state of Iowa and my last gig of the run was in Mason City, which is about three hours away from where Justin lives in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. I went up there and spent two days hanging out.”

Hornsby then invited Vernon to sing on his 2016 album Rehab Reunion, a folk-oriented outing on which Hornsby swapped his trademark piano for a dulcimer.

Next, “Justin asked me to play his beautiful Eaux Claire Music And Arts Festival, and to play the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in California with him.”

With typically wry self-deprecation, Hornsby adds: “I was the grandpa on the bill – probably by 25 years the oldest motherfucker on the stage!”

Since then, the pair have continued to collaborate, with Hornsby co-writing U (Man Like) on the just-released Bon Iver album, i,i.

“We actually just played a wedding together, about a month ago,” Hornsby adds. “So from Coachella to a wedding reception, we’ve run the gamut already, Justin and I!”

It’s far from the first time that Hornsby has collaborated with another artist in a long and constantly questing musical career of which his Top 40 hits in the 1980s were just the beginning. As early as the late 80s, he was lending his piano and accordion playing to albums by Clannad, Shawn Colvin and country star Tom Wopat. He co-wrote and co-produced the Don Henley hit The End Of Innocence and played piano on Bonnie Raitt’s iconic I Can’t Make You Love Me.

For the past decade, he’s been writing film and TV scores, including the music for Spike Lee’s Netflix series She’s Gotta Have It and his 2018 movie BlacKkKlansman.

“The success that we had early on opened up my musical world in an amazing way,” reflects the artist who has appeared on more than 100 records by everyone from Sting to Willie Nelson.

“I started getting asked to play and write with amazing artists from Robbie Robertson to Bob Dylan, Bonnie Raitt, Spike Lee… it just kept moving and moving.

“But then, it was off the radio,” Hornsby says of most of his post-80s music. “Critical acclaim in the press only goes so far in growing your audience and a lot of people in the hinterlands of the US have no idea about any of that. A lot of people who have been coming to hear our band don’t know that I’ve made a record in the past 25 years!”

Bruce Randall Hornsby was born in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1954. He came from a musical family. His father played saxophone with his uncle’s band Sherwood Hornsby & The Rhythm Boys. His grandfather organised music in schools and played church organ on Sundays.

“I had a Vox guitar, because that’s what they played, when I was 12 or 13 years old,” he reports.

For much of his teens, Hornsby concentrated on athletics and basketball, before rediscovering the piano.

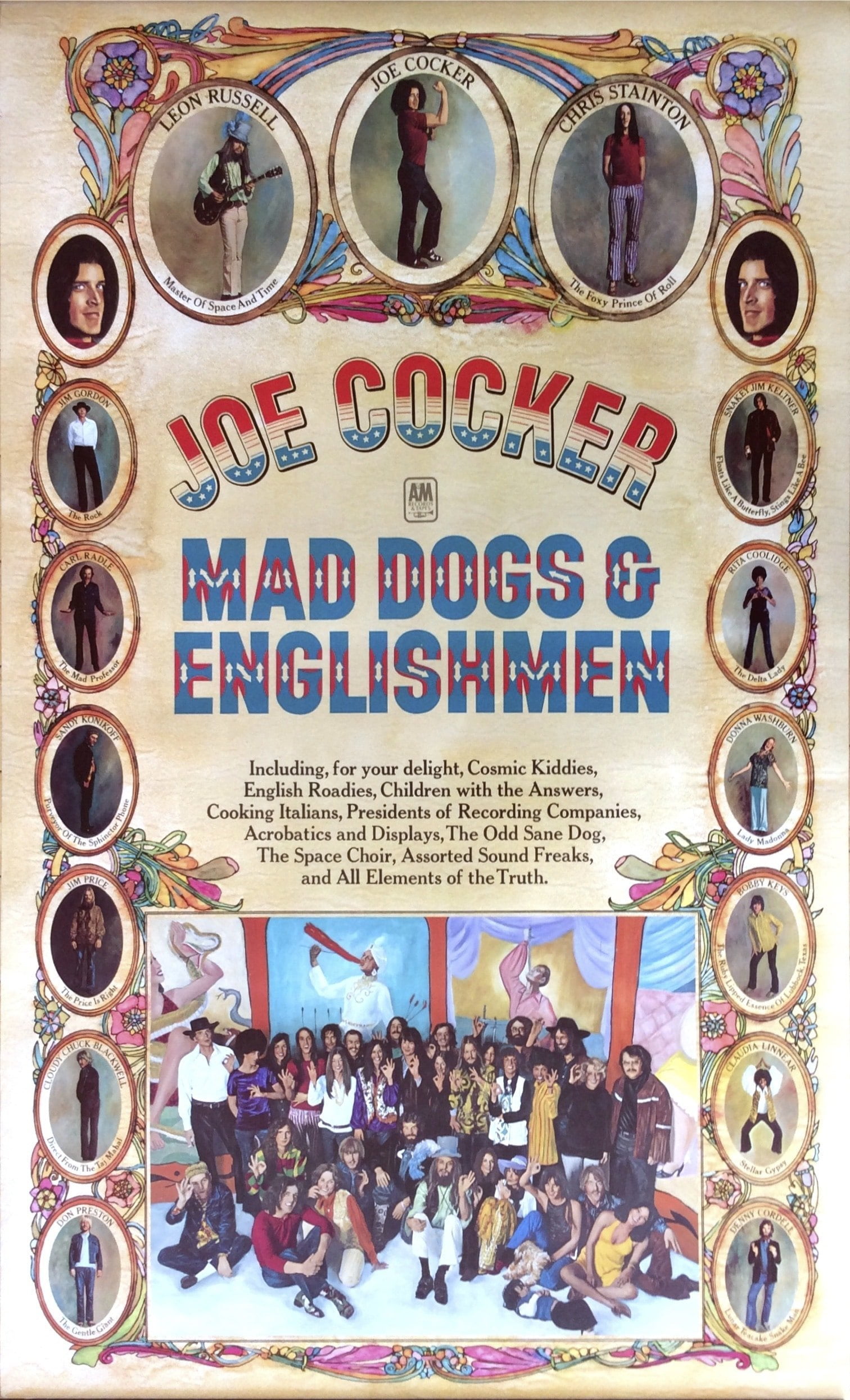

“I was a late starter,” he says of his keysmanship. “My brother turned me on to the Joe Cocker album, Mad Dogs And Englishmen, on which the great Leon Russell was the band leader and piano player. He also turned me onto Elton John’s third album, Tumbleweed Connection, which was the one Elton record without a hit on it but which may still be my favourite of his records. Those albums blew my mind and made me want to take up the piano.

“You have to imitate before you can innovate. You have to learn the language. So I was doing that by learning Leon Russell songs, Joe Cocker songs and Elton’s songs.”

School Of Rock

Hornsby was schooled in music at the University of Miami and the prestigious Berklee School Of Music in Boston. But he also learned his craft the rough way, playing electric piano in his elder brother’s band Bobby Hi-Test And The Octane Kids. They specialised in Grateful Dead covers at frat parties so wild that chicken wire protected the band from flying bottles.

He subsequently formed his own Bruce Hornsby Band and in 1980, with help from Michael McDonald and Jeff Baxter from The Doobie Brothers, who saw him playing in a Steak & Ale restaurant, signed a song publishing deal with 20th Century Fox, along with his younger brother and sometimes co-writer John.

A couple of his and John’s songs wound up in a bar scene in the 1982 film Making Love. But generally, he says of his time at Fox, “We were not successful. We were the opposite of success, and when I didn’t get a record deal they kicked me to the kerb.”

He spent the next year, “kicking around LA, playing on demos for other writers and doing the odd session.” In 1983, he was hired as Sheena Easton’s piano player and spent the next two years touring with her. You can spot him in the background of Easton’s video for Strut.

“All that time, I was trying to get my own thing going, and Sheena was always a big fan of what I was doing. You could walk by her dressing room, with the door closed, and hear her warming up by singing along with my demos, which I’d given her because she was a fan.”

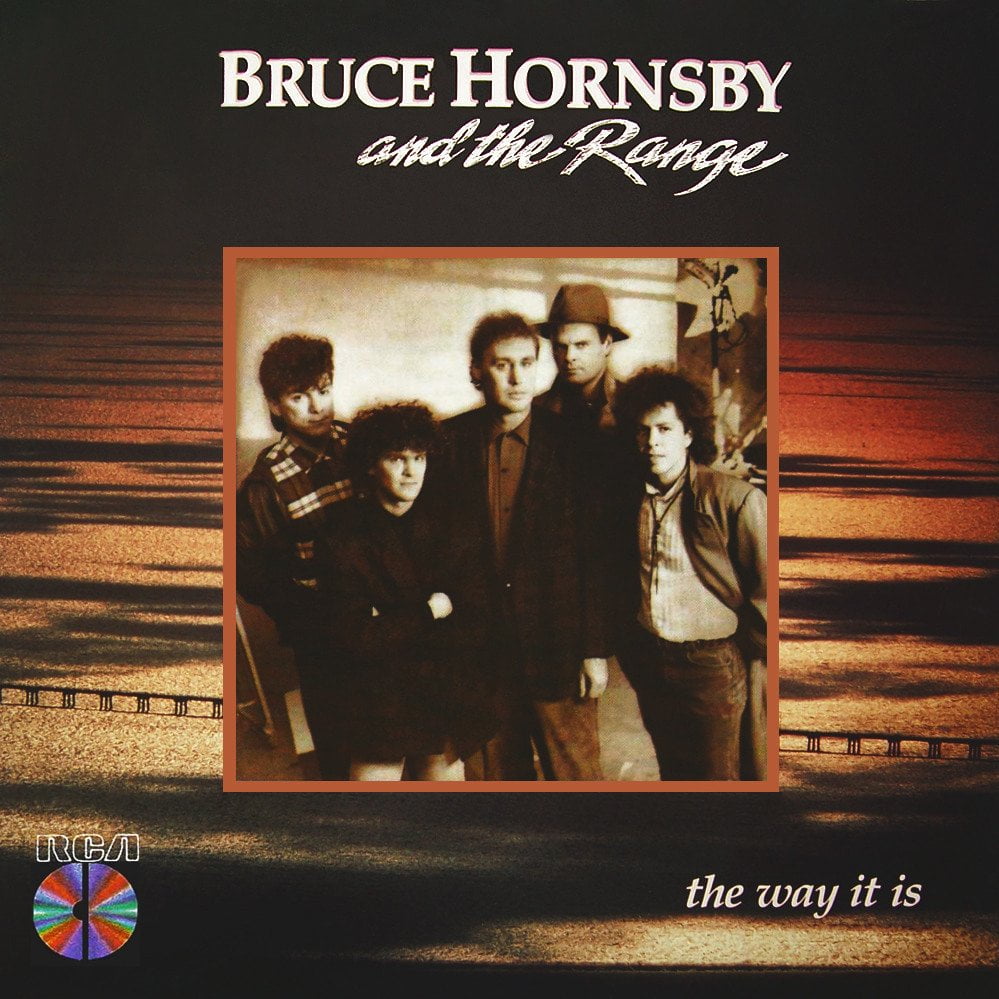

In 1985, Hornsby and his newly-formed band The Range, signed with RCA, largely on the strength of his demos for Mandolin Rain and The Red Plains.

Hornsby’s debut single, Every Little Kiss, peaked at a disappointing No.72 in the US but his fortunes changed dramatically when Radio 1 in the UK latched onto the title track of his first album, The Way It Is – a stirring song about social injustice delivered in a deceptively mellow manner over an irresistible piano hook.

“Our album came out in April in the States and it was gradually, ever so slowly gaining attention on what’s called AOR radio, which meant album-oriented rock. So I was on the radio with John Mellencamp, Tom Petty, Springsteen’s Tunnel Of Love and records like that.

“We weren’t on Top 40 radio at all, but the record was slowly gaining interest. Then, the record was coming out in the UK. The RCA promotion exec was a bit befuddled by it. He gave it to a friend of his at Radio 1, producer Mik Wlikojc, and said, ‘Here’s a record we don’t know what to do with. It’s kinda country, kinda jazz. Take a listen and see what you think.’ Mik picked this one song, put it on Radio 1 and boom, there it went.

“Within two or three weeks we were flying over to do the Wogan show and Top Of The Pops.”

The Way It Is reached No.15 in the UK, then crossed the Atlantic to become the most played song on American radio in 1987. It topped the charts in the US and Canada, helping to propel its parent album to sales of more than three million. The song also topped the chart in the Netherlands and was a substantial hit around the globe.

Hornsby, however, was not entirely happy in the spotlight. “I think I was pretty bad at being a pop celebrity,” he chuckles. “I was 31 when the record broke and that’s late in the game for the pop world.

“On one hand I handled it fine, because I didn’t take it very seriously. We were pranksters, fooling around. We felt like idiots lip-syncing and you can see videos of us on old Dutch TV shows where we were just taking the piss out of the whole thing.”

The hits continued, more so in the US than the UK, with Mandolin Rain (No.4), a reissued Every Little Kiss (No.14) and Valley Road (No.5), while 1990’s Across The River topped the Canadian chart. Bruce and his brother John also found time to pen the Huey Lewis And The News No.1 Jacob’s Ladder in 1987.

Moving Forward

For all his success in the 80s, however, Hornsby looks back more fondly on the music he made in subsequent decades.

“I’m definitely not someone who listens to the old records and goes, ‘Oh, man, how great I was.’ Frankly, I have a hard time listening to my first couple of records. I’m not a fan of the singer who sang those songs. I think my voice is much stronger now. It’s more expressive. Just looser.

“I’ve been moving my music forward since the third record – the last Range record, A Night On The Town [the 1990 release that included Across The River] – and especially the fourth record, Harbour Lights [his first solo release, in 1993]. I feel that’s when the music got interesting.

“It’s complex. It’s not just a guy playing a chord progression and singing over it, which is what most popular music is. And I love doing that as well. But I’m also interested in playing my instrument well. I’m interested in virtuosity on the instrument.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Hornsby qualifies. “I love to write simple music and I do it all the time. But the people who wanted me to sound the same? I apologise to them, because I’m not that person. I’m looking to grow and evolve.”

Playing The Hits

On his solo piano tour in November (his first UK dates in six years and his first on the Continent in a decade-and-a-half), Hornsby says he will be visiting the full spectrum of music that’s he’s released in the past three decades.

“Someone who comes to the concert will hear the hits – the nostalgia lover’s reason to be there. I will placate that person who has not really continued to follow what I do. But I also owe it to myself, and I owe it to them, to deal with a lot of areas of music that I’ve developed since then that I think are of great worth. I’ll definitely be playing some of the new record because it’s gotten such attention and validation for me – which is, of course, very gratifying. Also, it should be known that I take requests.”

Looking towards the future, Hornsby is currently “deeply involved” in making his next album.

Will Justin Vernon be on it?

“Justin has been on my last two, so I’m probably going to leave him alone,” Hornsby laughs. “He’s actually already on my next record as a writer, because some of the songs that are earmarked for it are ones we worked on in my second visit to Eau Claire last year that haven’t seen the light of day yet. We worked on six or seven things in the five or six days we were at his April Base Studio when we worked on Cast-Off for Absolute Zero.

“But he’s not singing on anything yet, and he’s one of the great singers, so that’s what people would want to hear. Right now, there are no guests, because I only started this recently. But there will be. yMusic [the contemporary classical sextet that features on Absolute Zero] will be on it. So will [violinist and arranger] Rob Moose, who’s all over the new Bon Iver record as well.

“So maybe Justin will sing on it and maybe he won’t. I’m definitely not gonna badger him!”

Douglas McPherson

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.