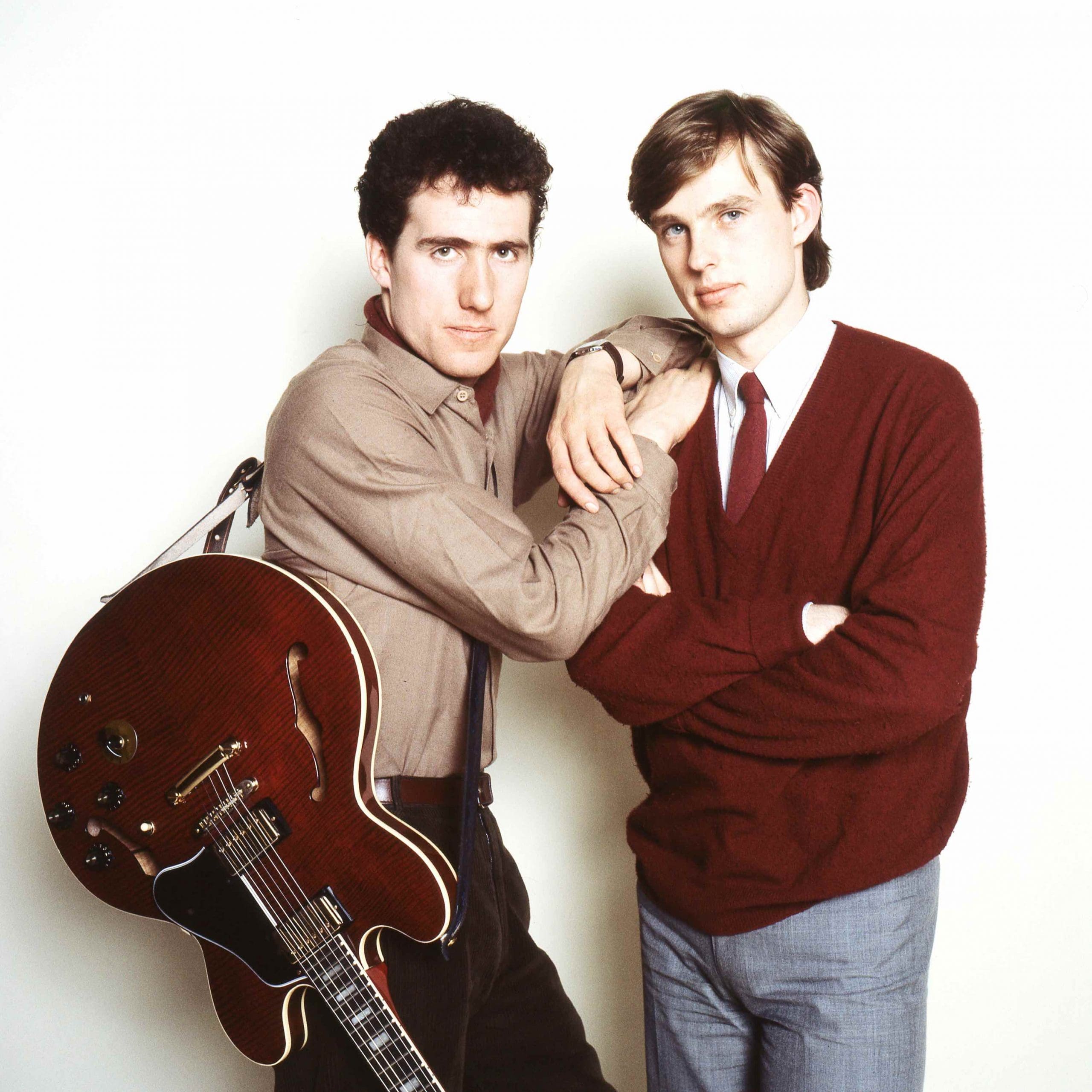

Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark began as an art project that played one gig for a dare. Forty years later, Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphreys’ art project has sold millions of records, split up in a mess of bad drugs and worse finances, only to reform stronger than ever. “There’s still an enormous amount of drugs on our tour bus,” they tell Classic Pop. “But now they’re just prescription ones keeping us alive.”

OMD singer Andy McCluskey calls Paul Humphreys “The Surgeon”. The keyboardist in turn refers to the frontman as “The Butcher”. “I cleave ideas with a big chopper and throw them out,” Andy explains. “Paul surgically makes it all fit together. It really does work.”

It’s a neat summary of how Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark have operated since their first gig at influential new wave club Eric’s in Liverpool in 1978. But it’s also a slightly jokey remark which highlights the probable reason OMD aren’t more revered in electronic music: they take their music seriously, themselves much less so.

Debut single Electricity was groundbreaking synth-pop and one of the first five releases on Factory Records. Its B-side Almost is cited by Vince Clarke as the reason he took up playing keyboards. OMD’s =1983 album Dazzle Ships flopped at the time but has gone on to be named by The Killers, Arcade Fire and Radiohead as an influence. And you won’t get a better late-period synth-pop classic album than OMD’s most recent record, 2017’s The Punishment Of Luxury. Their original drum machine Winston is on display at a museum in Liverpool and further museum displays have been dedicated to them in Arizona. Andy has even co-written for the band with Kraftwerk’s Karl Bartos. If only OMD were more earnest and po-faced, they’d have statues erected in honour of their influence on electronic music.

On Their Own Terms

That OMD are still making albums as vital as The Punishment Of Luxury and its predecessor English Electric is easily explained. “We’re in the fortunate position that we don’t have to keep doing this,” admits Paul. “We don’t have the pressure of having to write an album to survive, like we did in the 80s. We’re doing what we really want when we want, so in some ways we’re back in my mum’s room in the 70s, mucking about.”

Paul now lives in London, while Andy is back in the Wirral, close enough to where the pair grew up that, from his garden window, he can see the large art deco pub The Railway Inn that dominates the small town of Meols where Paul and Andy met at Great Meols Primary School in the mid-60s. When OMD make an album, Paul will stay at Andy’s house for a week every month. They’ve remembered that OMD need to be in the same room to write songs. Their 2010 comeback album History Of Modern was mostly written separately, swapping ideas by email, and they think it suffers slightly because of it. “History Of Modern was a little bit taped together,” Paul frets. “There’s some good stuff on it, but we’ve got to be in the same room for the sparks to fly,” adds Andy.

It’s easy to see why Andy and Paul get on, not just creatively. Andy is the louder of the two, a born storyteller. Paul is more laid-back, but just as entertaining. “We’re a lot calmer and have a more loving relationship now,” explains Paul. “We’re old men who have put our issues aside. The problems you had at 20 disappear when you’re 60. At our age, if you’ve got your health and you do a job you love, fantastic.”

According to Andy: “I have an intensity and a drive which can be sharp-edged and monochromatic. Paul has more of the softness and colours.” Professionally, Paul notes: “Andy is a fantastic lyricist who can write a great melody hook, and I can write a great keyboard hook. If we bring those two things to the table, we’re pretty much guaranteed to have something…” He stops, typical modesty kicking in. “…quite good.”

Andy can’t resist one affectionate dig at his bandmate, noting: “Paul tends to be a bit last-minute. I wouldn’t say he’s lazy, but his definition of the word ‘busy’ is different to mine.” Andy recalls confronting Paul while making English Electric, forcing the keyboardist to admit he’d written that week’s batch of ideas on the train to Andy’s house from London that day. They were 10 reasonable variations on the same idea and another that Paul had dismissed as “some noodling I did as I got to Runcorn”. That “noodling” was the killer melody of what became the album’s lead single, Metroland.

Any arguments in OMD now tend to be confined to football. Andy, drummer Stuart Kershaw and keyboardist Martin Cooper are Liverpool fans, while Paul supports Manchester United. “Can you imagine?” laughs Paul. “A die-hard United fan growing up in Liverpool. My family were United for generations, so I had no choice. Football is the hardest part between us. I’m an outsider in a band of outsiders.”

Paul’s comment is throwaway, but OMD have always been DIY outsiders. As lads from the Wirral, they were on the fringes of Liverpool’s Eric’s scene, despite going every week. Although they were playing an early version of Electricity, back then Paul and Andy were part of eight-piece prog rock band The Id, with long hair and flares. Hearing Autobahn by Kraftwerk was “the first day of the rest of our lives”, according to Andy. “Paul and I thought, ‘This is the future’, and all our musician mates thought Kraftwerk were shit.” Paul adds: “The reason we became a duo and used Winston as a drum machine is because nobody else wanted to play our weird electronic rubbish.”

It wasn’t until Eric’s DJ Norman Killon played The Normal’s Warm Leatherette that Andy or Paul realised anyone else was making electronic music in Britain. Weeks later, fellow Wirral band Dalek I Love You performed at Eric’s with a drum machine, tape machine and synths. The two events made the pair emboldened enough to step aside from The Id to play as Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark at Eric’s Thursday night try-out show. It’s only in hindsight that the pair are able to assess why there was enough of a buzz about OMD to be snapped up by the then-new Factory Records.

“It was only a few years before that we’d been 12-year-olds watching Slade and T-Rex on Top Of The Pops,” Andy explains. “We had absolutely no intention of grandly claiming, ‘We’ll write a new form of pop music with electronic melodies’, because we thought we were an entirely experimental art project. But we had three-minute glam-pop songs in our DNA.”

Typically for OMD’s fringe status, it was Tony Wilson’s wife Lindsay who told her husband to sign the duo, somewhat against the Factory boss’ instincts. “We owe our entire career to Lindsay,” insists Paul. “Tony’s enthusiasm was so infectious and exciting, and obviously Factory had an amazing artistic sensibility. Peter Saville was pushing the boundaries of what sleeve art could be, right from the start with his black-on-black cover for Electricity.” However, Tony insisted OMD could only have a one-single deal with Factory. “Tony told us: ‘You guys are the future of pop music and we’re too small to handle you. You go and be a successful band,’” recalls Paul. “Our response was, ‘Fuck yourself, Tony, we’re not the future of pop! We’re an art band.’ We were both right, we were a pop band as well as an art band, but only Tony identified the pop side at the time.”

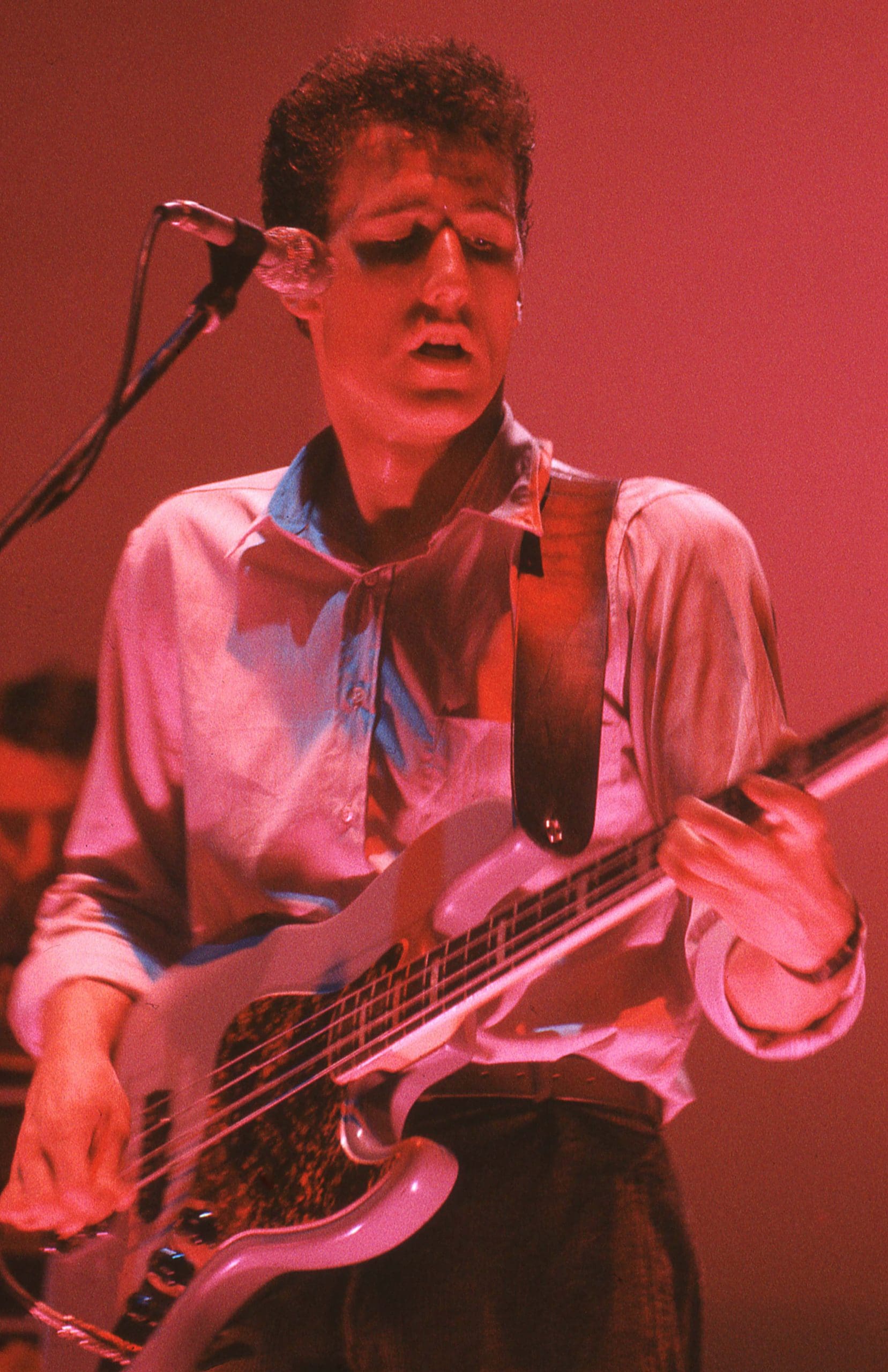

Andy remembers the first of OMD’s 29 Top Of The Pops appearances as a “crushing disappointment” as the stage was so small and the set was held together with gaffa tape, while “the audience were mown down by boom cameras”, but the show helped their unlikely stardom, as well as infighting on the nascent synth-pop scene. “Most of the early electronic bands didn’t know each other existed in the pre-internet days,” he explained. “Once we did, there was a lot of mutual suspicion. You’d glower at each other at Top Of The Pops, arms folded, going, ‘We were doing this before you.’” Amazingly, OMD and The Human League didn’t properly meet until they both played a Let’s Rock festival in Exeter last year. Andy: “I went straight up to Phil Oakey and said, ‘Phil! Apparently we hate each other!’ We had a laugh about it all and a picture together, but back then the only thing that bonded electronic groups was the fact that all the other bands hated us even more than we hated each other. And that went double for the rock press.”

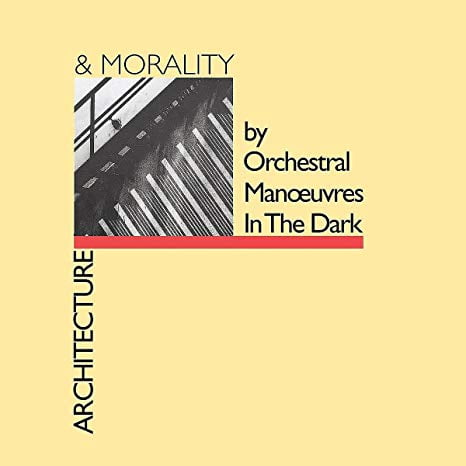

Despite the success of Architecture & Morality, Dindisc folded, leaving OMD to be swallowed up by Virgin. “We still thought of OMD as a conceptual art piece in the guise of a two-piece band,” explains Andy. “Whatever we did, people bought more of it. We didn’t really have a working relationship with Virgin. They asked us, ‘How do you two work?’ and we explained, ‘You leave us alone. We’ll phone you up, tell you which studio and engineer we want, you’ll pay for it and it’ll sell millions.’ Virgin went, ‘OK, fine.’ And then we made Dazzle Ships.”

One of the ultimate examples of a mega-selling band making a genius, yet wildly uncommercial album, 1983’s Dazzle Ships saw OMD sample Communist radio stations the duo found on shortwave radio and write songs about genetic engineering. Andy recalls: “Friends had been saying to me, ‘You’re a political guy, so why are you singing songs about dead Catholic saints and being so dreamy?’ My reaction was, ‘OK! Right! That’s it, it’s time to get more political.’” Paul believes Dazzle Ships is the perfect example of straddling OMD’s pop and art sides. “Becoming pop stars was an unfortunate by-product,” he states. “We wanted to be the opposite of New Romantic, so we thought, ‘Let’s look like boring bank clerks.’ But when we did gigs, the first few rows of fans would dress as boringly as we did. Musically, we were pushing boundaries as far as we could. At one Virgin meeting, the head of A&R asked us, ‘Come on guys, are you Stockhausen or ABBA?’ Andy and I said together, ‘Can’t we be both?’”

Dazzle Ships’ lead single Genetic Engineering literally vanished off the radio. When it was first played on Radio 1, Andy and Paul listened in horror as the song disappeared off air, because its bass drum was too booming for the BBC’s compressors to cope with. “We looked at each other and said, ‘Oh, we’re fucked!’” says Andy. “And we were. The bass drum crashing out was after the song’s intro consisted of a toy piano and typewriter, don’t forget. When Dazzle Ships came out, the public went ‘No, that’s just a bit too weird for us.’ At the time, Virgin joked through gritted teeth that Dazzle Ships shipped gold and returned platinum.” Paul notes wryly: “I can see why it wasn’t a hit. We’re incredibly proud of Dazzle Ships, but when we listened back to the individual parts when we reformed to play live again, I did think, ‘Wow! What were we on?’”

After its multi-platinum predecessor, Dazzle Ships sold just 200,000 copies. The reaction was 1984’s Junk Culture, whose title signified, in Paul’s words, “We got scared and thought, ‘Let’s abandon Stockhausen and become ABBA for a bit.’” Locomotion is an incredible earworm, but it marked OMD starting to play safe – with America finally catching on to the group at their artistic nadir when If You Leave was featured on the Pretty In Pink soundtrack.

OMD’s American management didn’t help, cajoling the band into countless US tours where they lost more money until If You Leave finally succeeded. It included support on two of the most notoriously debauched tours of all time: The Power Station’s in 1986 and, two years later, playing before Depeche Mode to 95,000 fans at Pasadena Rose Bowl, captured on Anton Corbijn’s groundbreaking documentary 101. “Playing stadiums was as frightening as it was fun,” admits Paul. “You settle in after two songs, but at first it’s terrifying. I still had good eyesight then, so I could see those 95,000 faces all the way to the back.”

Asked which of the tours was more crazed, Paul plumps for The Power Station. “The drugs were insane in the 80s and it was particularly insane in 80s America,” says Paul. “There was just an enormous amount of drugs on The Power Station tour. Everybody was on drugs. You’d go backstage and people you’d never seen before in your life would be there with a giant mirror, racking out huge lines of coke, shouting over, ‘Want one?’ Quite how we managed to get through those times, I don’t know.”

The final straw came when OMD returned home after playing stadiums on the Depeche tour to be told by their accountant that the royalties had run out and they owed Virgin £1 million.

Escape To LA

While Paul moved to LA so his then-wife could be near her family, Andy kept the OMD name. 1991’s Sugar Tax was a successful return to the straight-up pop of Locomotion. “I’m really pleased with Sugar Tax,” says Andy. “Walking On The Milky Way is one of the best songs I’ve ever written. It made the Top 20 despite Radio 1 refusing to play it and Woolworths not stocking it, which was amazing. I was terrified without Paul, though. You won’t see my name anywhere on Sugar Tax as I was hiding behind the OMD name. But I forgot the lessons I’d learned, because I made the Liberator album far too quickly immediately afterwards.”

Despite their split, Paul co-wrote a handful of songs on Liberator and Universal after Andy moved to LA, too. “Our lawyers fell out, not us,” laughs Paul. “It got bitter between Andy and I briefly, but that was down to what our lawyers were saying about us.”

It meant the offer to reform, initially for a German TV show in 2005, was able to happen with the minimum of fuss. A nine-show comeback tour turned into 49 dates then three albums and counting.

Entering their sixties, OMD really are living the dream of keeping their health in a job that they love. Well, mostly. “I have arthritis issues,” reveals Paul. “It happens to all keyboard players. It’s a joke in the band that there’s still an enormous amount of drugs on our tourbus. But now they’re just prescription drugs keeping us alive, instead of being recreational.”

Click here to read more Classic Pop interviews

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.