Grief and anger left Ben Watt stuck in a dark place – but now he’s emerged into the light with a reflective, deeply personal new album. Here, he talks life, death and everything (including the girl) in between with Paul Kirkley…

Three years ago, Ben Watt came off the tour for his last album, the critically acclaimed Fever Dream, with every intention of cracking straight on with the next one. And then…

“I suddenly hit a brick wall,” the 57-year-old tells Classic Pop. “I think I’d been working so hard, I hadn’t completely digested the death of my brother in the previous year, and just a whole stack of emotional things that were kind of building up. I was unable to do anything for a quite a bit, which I found very dispiriting.

“I was angry, I think, in the way that grief brings anger,” he reflects. “My sister had died in 2012, also young. She was only 58 and that was very much a springboard for some of the ideas that went into [2014 album] Hendra. The last thing I expected was my brother to die a few years later. He was only 62. So it was a tricky time. My mum died in the middle of it all as well, so…” He lets out a rueful laugh. “I mean, I don’t want to carp, but I’m just trying to lay out some of the things that were going on personally in my life in the run-up to writing this record.”

The source of his frustration was political as well as personal. “The news was just full of all this stuff, all the time, everywhere in the world. It just seemed to be endlessly gloomy and… I don’t know. I just went into a bad space for a while.”

Expanding on Ben’s signature jazz-folk template, the record places piano and double bass against a bed of skittish electro-acoustic drums, analogue synths and found sounds. Lyrically, we find our narrator wounded yet defiant, bloodied but unbowed as he reflects on an intense period of anxiety and change, while holding out for the promise of a better tomorrow.

His grief manifests itself most explicitly in songs like the raw, impassioned Retreat To Find, on which he sings of rooting out a place in his heart “where I can outface death”. “It’s a song I wrote after a very vivid dream I had about the death of my brother,” Ben explains. “I think it’s about how death is approached. My brother was an Anglican priest, and obviously death to him meant something very different to what it means to me, being an atheist. That’s what’s in that song – is death a godless experience? Or is there something at the end of it for you?”

Summer Ghosts, meanwhile, takes us on a journey through the streets of Hull – and through Ben’s own past.

“I went back to Hull in 2017 with Tracey,” he recalls. “We were invited to give a talk as part of the City Of Culture celebrations. And that’s of course where we’d met, where we’d been to university, and where we first made a name for ourselves.”

In fact, they’d both arrived in Hull having already released solo records on the same label, Cherry Red. Tracey was also a member of post-punk outfit Marine Girls, and on their first night as freshers, Ben put out a Tannoy announcement in the student bar asking if “Tracey Thorn of the Marine Girls” could please come to reception. (Long story short: reader, she married him – though not for another 27 years, after they’d made 11 albums and three children together).

“The morning after we did this appearance, we just went for a really long walk through Hull, around all the places we remembered,” Ben continues. “And I had very mixed feelings about it. On the one hand, I felt very affectionate towards it. I also found it quite startling how little had changed in many ways – how a lot of it seemed incredibly familiar, and seemed to have just stood still. And yet, there were these kinds of beacons of change – all the art and regeneration that was done as part of the City Of Culture, the refurbishment of the art gallery where Tracey and I used to have a cup of tea on winter afternoons. And it made me think that we are very much tied to our past, in very different ways.”

“Long, long gone,” confirms Ben. “I think for a while it was turned into the Hull Business Development Centre. But when we were up there, that seemed to have closed down as well…”

“When you look back, you feel you haven’t travelled far,” sings Ben on Summer Ghosts. “I think we all feel that, don’t we?” he tells CP. “We’re all the product of how we grew up, the people we’ve known, the experiences we’ve had. It doesn’t matter how far you travel, you’ll always take yourself with you.”

Gorgeous recent single Irene – featuring guest guitar and vocals from Low’s Alan Sparhawk – also broaches the subject of nostalgia, and the sometimes strained relationship between musician and audience (“They yearn for some golden age/ The time they first heard you on the stage”).

“I’m very much of the opinion that I’m still trying to create, still trying to write, still trying to do what I always wanted to do,” says Ben. “I’ve realised that I would rather play new material to hundreds of people than ancient material to thousands. That’s the trade-off you have to make.

“I don’t think I’d be particularly happy out there on the nostalgia circuit having to perform an album I made 35 years ago in its entirety.

“I don’t want to be too negative about it,” he adds. “There’s a place for that. But not to the exclusion of all else.”

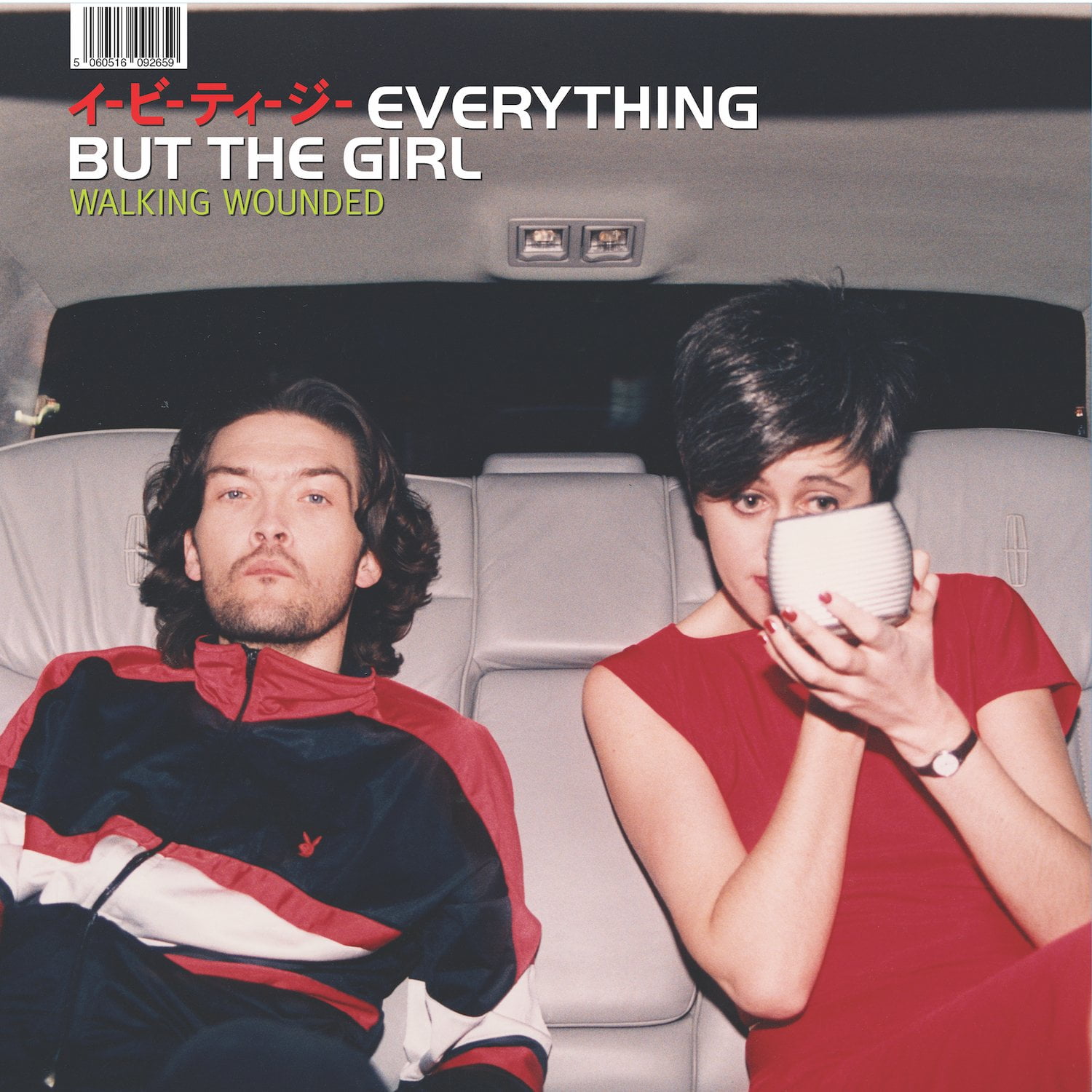

The latter was undoubtedly driven in part by Todd Terry’s dance remix of Missing, which gave Everything But The Girl their biggest worldwide hit (peaking at No.2 in the US), while Ben has spent much of the past 20 years developing his own club credentials as an in-demand DJ, remixer and label boss.

For all his reluctance to trade on former glories, surely Ben understands people’s desire to hang on to the songs, like Missing, that have soundtracked their lives?

“Of course,” he says. “I’m very proud of Missing, and everything it represents. I think we’re very lucky that our biggest hit was a track we’re both very proud of. So yeah, it’s a good memory, that one.” Good memories also penetrate Storm Damage’s dark clouds – not least on Festival Song, which closes out the album with Ben recalling a happy evening spent watching Radiohead performing on the beach in Barcelona; losing himself in the music, he allows himself to “let go, for a while, let go of the world, free from everything”.

Indeed, for all its sturm und drang, the record is shot through with a defiant optimism, most keenly encapsulated on the self-explanatory Sunlight Follows The Night. Having broken through that year-long mental logjam, would he go so far as to describe himself as… happy?

“Yeah, I think as far as any of us are,” he says, cautiously. “There are things that drag us down, there are things that lift us up. I’m very proud to have got this record finished in the shape that I wanted it to sound like, and I’m really looking forward to touring with it. Family life is great – the kids are grown up, all off at university now. We all still get on brilliantly as a family, and Tracey and I are still together after all this time. So, of course, there are amazing things to celebrate.”

A few years ago, Tracey stated in an interview that “people have an idealised sense of our life together – they think we’re skipping hand-in-hand through a hedgerow.” Ben isn’t sure about that. “I think people probably imagine it as it is, actually,” he says. “We’re in our 50s now, and life has its ups and downs. But people do like to celebrate the fact that we have lasted this long. And I think it is something to celebrate.”

“It was a massive life-changing experience,” he says now. “I was 29 years old. I went into hospital for nearly three months, nearly died several times, spent three weeks in intensive care, had four or five life-saving operations, and came out of it both physically and psychologically very changed. I don’t think anybody goes through an experience like that without some kind of legacy.

“On a day-to-day basis, the thing that follows me around is the fact I still have to take the medication to keep the disease at bay. And I have an altered diet because of it. That’s something I have to confront every day. So it’s… there, as a companion, if you like, every day I wake up. It doesn’t prevent me from performing and travelling and leading a normal life. But I suppose it’s a little shadow on the shoulder all the time.”

When their children – twin daughters Jean and Alfie were born in 1998, followed three years later by son Blake – were young, Tracey took a decision to “disengage” from music for a while. But Ben still felt compelled to, in his words, “be creative, driving forward, answering the unanswerable, seeking out the meaning of life”. CP wonders if he’s any closer to finding those answers?

“Do we ever?” he ponders. “It’s probably why I’m still doing it.”

What if… there simply isn’t a meaning of life?

“Well, there isn’t one,” he says, decisively. “But we try to impose one. That’s how we stay sane.”

Paul Kirkley

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.