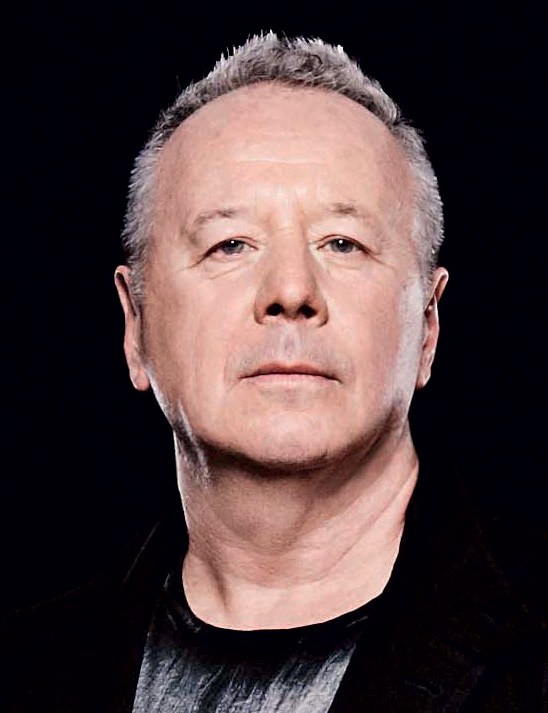

With Simple Minds’ 1989 album Street Fighting Years getting the reissue treatment and a new studio LP harking back to their dancey roots taking shape, Jim Kerr and Charlie Burchill tell John Earls about panic attacks, nuclear submarines, Lou Reed’s unlikeliest addiction and one of the most bizarre No.1 singles the charts ever experienced…

Late last year, Jim Kerr wrote what he thought was one of the best ballads of his life. He’d turned 60 in July, and wanted to write about the wisdom he’d acquired along the way. “I’m not going to write a song about turning 60,” admits Jim. “But, let’s just say, I considered the challenge of writing about getting older.” Jim and guitarist/ keyboardist Charlie Burchill, friends since they were eight-year-olds in Glasgow, created “a softer idea” than usual: “Maybe it was Christmas coming on and me getting sentimental,” as Jim puts it. “It’s the kind of song that, if Neil Young did it, people would say, ‘That’s amazing! The guy is so honest, he’s writing from the heart.’ I played it to a couple of people, who went, ‘Oh wow! That’s really sweet.’”

Despite this early positivity, the ballad is definitely not getting released – because Simple Minds’ manager vetoed it immediately. “He heard it and said, ‘Fucking no. You’re not that old. Leave it out – you’re not fucking Clive Dunn!’” Jim laughs casually, utterly unconcerned at his idea being squashed so brutally. Simple Minds may have sold more than 60 million albums, but if they get compared to the Dad’s Army actor who sang Grandad…? So long as it’s a funny story, Jim Kerr would rather tell that than be earnest about his band’s reputation.

Back in the big time

In 2020, Jim and his lifelong double-act partner can afford to be relaxed. Starting with Simple Minds’ 16th album Big Music six years ago, the band have been on top again, back to the experimental force when they rampaged out of Scotland in the late 70s, able now to commandeer arenas again. 2018’s adventurous Walk Between Worlds reached No.4 in the UK, returning Simple Minds to the Top Five for the first time since Good News From The Next World 23 years earlier. “A renewed confidence came with Big Music,” Jim acknowledges. “We thought we’d made a good record, but the reaction from the public was equally important. It’s propelled us ever since. The momentum these past few years, it feels great.”

Even in conversation, Jim is a natural showman, an expansive talker with a great eye for a yarn. He’s also a champion swearer, knowing exactly when to drop the F-bomb for comic effect. Charlie is quieter, but then most people are next to Jim Kerr. The other surviving founder Simple Mind, Burchill is more of a dreamer than his bullish pal. “We’re very different people,” he admits. “But Jim and I have always had a strange bond artistically. If we haven’t seen each other for a couple of months, the chances are we’ll have been watching the same movies and TV shows and read the same books. It’s just weird, how we’re drawn to the same ideas.”

Currently, that kinship means Simple Minds are heading back to the dancefloor. For three albums from 1980’s Empires And Dance through Sons And Fascinations/Sister Feelings Call to New Gold Dream (81/82/83/84), Simple Minds were at the vanguard of synthesiser experimentation. They never lost their desire but, once Waterfront made Simple Minds more radio-friendly, their sound certainly became more streamlined. Jim explains: “I said to Charlie when we started thinking about the next record, ‘I think it’d be good for Simple Minds to have a more dancey feel again.’ I meant that in terms of Simple Minds’ dance music: songs like I Travel and Love Song, with those kind of funk basslines running through them.”

Of six songs demoed so far, Jim says four are in that mould. It helps that Charlie’s become obsessed by the Moog One, a retro-designed piece of kit he describes as “a hybrid of a digital and analogue synth”. According to Jim: “A lot of our music flows from whatever new gear Charlie’s just bought. He gets really excited by an old analogue synth or some guitar effects pedal and it becomes the talisman of the album.”

Expanding horizons

Currently working with Andy Wright and Gavin Goldberg, their production team since Big Music, Simple Minds are likely to “throw other people in, too, to get a different perspective,” says Charlie. But the album is unlikely to appear until late next year, with Simple Minds spending most of 2020 on tour. “We haven’t played for about a year, when playing live is what we feel we do best,” Charlie reckons. “It makes sense to play again now. A lot of musicians look at such a long list of dates and go, ‘Aargh! Six months! What about my home?’, but Jim and I love it!”

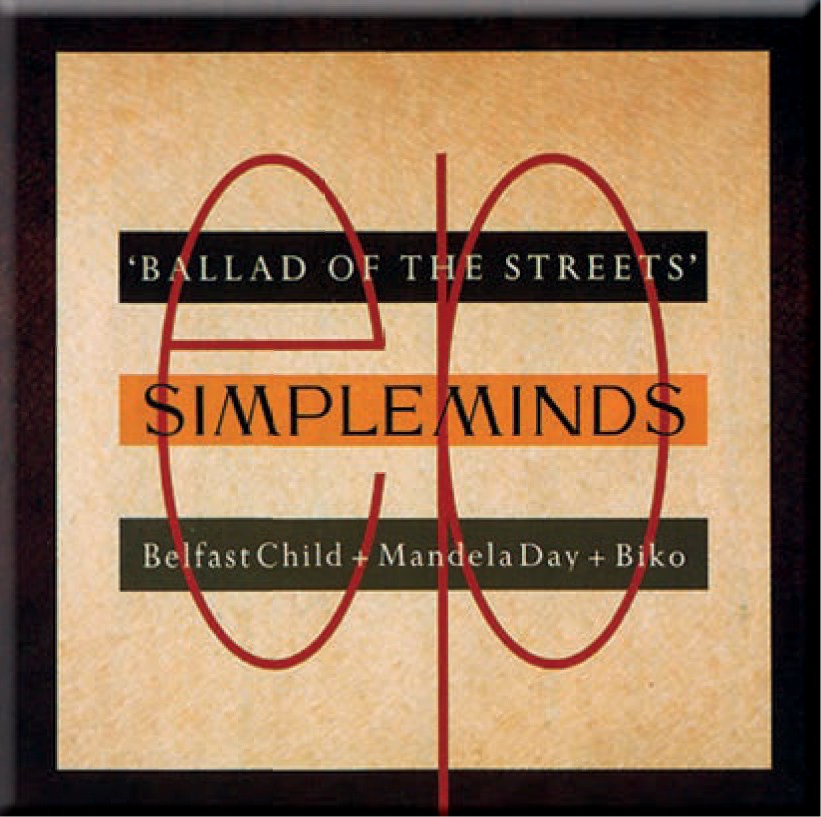

Charlie and Jim have nearly always been able to coexist happily. But, once megastardom hit, it naturally jolted the band massively. This month sees the reissue of Street Fighting Years – the album that confirmed Simple Minds as a stadium outfit and gave them their only No.1 single Belfast Child, but which also led to both bassist John Giblin and founding keyboardist Mick MacNeil quitting. Released in 1989, Street Fighting Years was intended to be a political synth-pop opus co-produced by Trevor Horn, but instead saw the Frankie Goes To Hollywood and ABC overlord turn Simple Minds into folkies. Belfast Child is a No.1 single based on a centuries-old traditional folk song that lasts for seven minutes. No wonder Street Fighting Years sent Simple Minds mad.

There’s a photo on the wall of Jim’s study at his home in Glasgow, of Simple Minds stood by the Berlin Wall on tour in 1979. “The world was a different place then,” says Jim. “We grew up in the Cold War. Travelling through Europe at an early age as we did, we were touched by a lot of those places which had a resonance from our childhood.” Talking about his father Jimmy, Kerr continues: “He was a construction worker, but he was a well-read man who was keen on informing us that the world didn’t finish at the end of our street – that’s where it began. Dad said we owed it to ourselves to know what was going on in the world.”

After 1985’s Once Upon A Time became their second No.1 album at home and made Simple Minds stars in America, Jim felt it was time to start writing about the outside world, rather than his own emotional landscape. This was, he admits, also because he was getting divorced from Chrissie Hynde, having married in 1984. “It wasn’t one of those brutal, ugly divorces,” Jim emphasises. “But the last thing I wanted to write about was myself. I didn’t want to sit licking my own wounds.”

Jim was aware of the backlash awaiting any songwriter trying to make sense of the politically turbulent times. Street Fighting Years discusses Greenpeace, South Africa’s apartheid regime, Northern Ireland and the Poll Tax introduced during the last years of Margaret Thatcher’s government. “The first thing people think is, ‘Who the fuck are you to say this and what world are you now living in?’,” admits

Jim. “But I take great pride in Glasgow, in 1981, being the first city in the world to give Nelson Mandela a Freedom Of The City award, when he was still vilified and being called a terrorist nearly everywhere else. The word ‘activists’ might be pushing it, but we were from that background. It was inevitable the strains of that would come out in our music.”

The highlanders

Jim, Charlie, Mick, John and drummer Mel Gaynor decamped to Glenstriven in the Scottish Highlands, where they’d built their own studio near an Army testing base. “We told Trevor Horn it’s where they test nuclear submarines,” laughs Jim. “You could get away with those stories in the days before checking on Google. Trevor was going ‘Whaaat?’ It is true submarines were tested there during World War II.” Charlie adds: “It was a great place to make a record, as it felt like we were a bunch of kids let loose in a beautiful isolated house. There were none of the distractions of an urban environment, so we were able to use our fantasy side more.” Recruiting Trevor and his right-hand man Stephen Lipson to produce Street Fighting Years was one of the great mix-ups of the 80s. “The bad news about that album and what I don’t like about it is the timing,” says Jim. “We’d had success beyond our belief and we were just on the verge of getting bored with our own thing. I don’t think we quite knew that, and we certainly didn’t talk about it, and it’s inevitable after 10 years that it happened. We saw hitching our wagon to Trevor and Stephen’s Fantasia production world as like strapping on rocket engines.”

There was just one slight problem with recruiting electronic pioneers to mix up Simple Minds’ sound. Charlie summarises: “Trevor and Steve wanted to come to us because they thought, ‘Great, we’ve got a band who can play for a change!’ and they could relax a bit more than usual while we did our own thing.” After six months of recording, obviously struggling, Jim decided to call Trevor in for a heart-to-heart.

“Before he came along, Trevor told me, ‘Jim, one of the reasons we wanted to work with you is we’re bored of our thing,’” recalls Jim. “So there we were, two camps bored of their sound, looking for the other to help. I just thought, ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake!’ I’m sure we didn’t give Trevor and Stephen the easiest time, and it says something they didn’t work together again after Street Fighting Years. We were a bit dead on our feet and it’s still a frustration that atmosphere was there.”

Despite the impasse, Jim and Charlie both speak glowingly about the childlike sense of wonder Horn brought to the studio. “Trevor is fearless,” says Charlie, while Jim adds: “He’d convince you anything was possible. If you think of Trevor’s music, so much of his budget goes into one or two big songs that the rest of the record ends up getting done pretty quick. There’s a bit of that in Street Fighting Years, but mostly he’d kick the tyres of a song over and over, trying it a dozen different ways, until something was there.”

Nine of the 10 songs on Street Fighting Years are over five minutes long. “There are only one or two where the length takes the feeling out of them,” Charlie insists. “But I look at some songs and think, ‘We nearly got there, but we didn’t quite get it.’ We worked harder on Take A Step Back than any other song on the album, but we never quite got it. There’s a lot of interesting stuff in that track and it’s a shame – in a different time or place, with different people, maybe somebody somehow could have unearthed what’s in the middle of that song. It happens.”

A moving experience

Honest about their frustrations, Jim and Charlie feel there are moments of magic – not least Belfast Child. It began when John wandered off from a band dinner at Glenstriven, playing traditional Irish folk song She Moved Through The Fair on a piano when Jim found him in the instrument room. “John is a deep guy, which was reflected in the music he played,” Jim explains. “I was captivated by this Celtic piece and, when he finished, I said to John, ‘Wow! When did you write that?’ and John replied, ‘About 200 years ago…’” In the pre-internet days, Jim began searching out covers of She Moves Through The Fair, with his favourite “a drunk Irish woman singing it in a pub in Camden, it was just so blues.” In love with the isolated Scottish countryside, Horn had already suggested Simple Minds should attempt a Celtic song. “I kept telling Trevor to fuck off,” Jim admits. “My dad brought me up on fiddles and banjos, and me becoming a punk was partly a rebellion against all that music. But Trevor had planted the seed, saying, ‘People love that stuff!’”

Politically aware as he was, Jim wasn’t certain he should adapt She Moves Through The Fair into a Simple Minds song discussing the Northern Ireland conflict. “I was nervous about it, because songs like that can seem mawkish, tokenistic and trite,” he says. “If you isolate the lyrics to Belfast Child, it can seem that way, even though our heart was in the right place.

But I think it’s different, because of the emotion in the song. Around the world, apart from the States, Belfast Child was huge. It connected, because it was a song loaded with emotion.” How does Jim feel about Belfast Child being the band’s only No.1 single? “Listen, any success is a great thing,” he laughs. “For that one week, it was the biggest song in Britain. If you’re asking, ‘Am I still glad I did it?’, then too right I am. To have the balls to mess around with that big a sacred cow of the folk world? Great! The folkies were going, ‘You can’t fucking do that to She Moves Through The Fair!’, when the folk world changes lyrics and melodies around forever. I thought, ‘Give me a break, you’re only jealous you hadn’t thought of it first.’”

That Belfast Child began with John Giblin walking out of a band dinner was typical of the bassist. The former Kate Bush and John Martyn player had made his Simple Minds debut at Live Aid in 1985, but left halfway through recording Street Fighting Years. “John was seven years older than us and I suspect we were quite brattish around him,” recalls Jim. “He’d done so much more than us in who he’d worked with and he was a lone wolf who didn’t say much. John’s stoicism added to his charm, but we always knew he was never going to sign up to Simple Minds’ youth club.”

Far more surprising was the departure of Mick MacNeil, who quit at the end of the Street Fighting Years tour in 1990. Charlie is laidback about the keyboardist going, saying: “We’d had so much success, it was the end of a decade, Mick wanted more time with his family… Ultimately, Mick felt he’d covered so much ground, there was nothing left to achieve. That’s great, as a lot of people don’t know when to stop.”

It’s easy to get a sense of the ambition driving Simple Minds forward 30 years later when Jim is asked about Mick. “I have to acknowledge everyone is different,” he considers. “Me and Charlie are marathon runners, Mick’s a sprinter. But I still think, ‘Fuck him. I wouldn’t like to be in the trenches with you, Mick. Go on, go home!’” Jim’s laughing as he says it, and speaks warmly of meeting Mick for the first time in decades, when he guested on Simple Minds’ version of Dire Straits’ Brothers In Arms for Trevor Horn’s recent covers album Reimagines The Eighties. Jim reveals: “Mick said he didn’t regret going, and I’m really glad about that, because it’d be awful if he did.”

Sound of the underground

Nonetheless, the singer can’t really understand why anyone would walk away from being in a successful band, saying: “Charlie and I are manic about the band, because we’ve never got bored with it. As much as we’ve all driven each other nuts at times, you can’t quit, because you’re so lucky to have it. People are invested in you. The amount of people who want to be in a band, compared to the tiny percentage of people who get the chance of doing what we do? I feel a great sense of obligation to that.”

As driven as Kerr and Burchill are, they’re amateurs compared to former Velvet Underground frontman Lou Reed, who sings on ecology anthem This Is Your Land.

One of the first songs written for Street Fighting Years, Jim happened to sing a verse impersonating Lou, but couldn’t work out what to do with it as the recording deadline neared. Trevor Horn suggested “Why not ask Lou Reed?” Jim recalls: “I told Trevor, ‘What are you talking about? He’s the world’s biggest curmudgeon!’ A friend was Lou’s PR at the time – she’d phone me in tears, going, ‘He’s a fucking nightmare.’”

Nightmare or not, Lou agreed when Trevor called him. Jim and engineer Heff Moraes – “a 16-year-old and the world’s biggest Simple Minds fan” – were dispatched to Paris to record Lou’s vocals. “Walking through the airport, I had my first ever panic attack,” Jim recalls. “I told Heff, ‘You’ll have to do it. What am I going to say to Lou Reed?!’ Heff was so sweet, saying, ‘What are you talking about? You’re Jim Kerr!’” Jim had pulled some strings to get a table at Paris’ most in-demand restaurant for their meeting, saying:

“It didn’t look like it, but Lou loved the world’s great restaurants. At least I had the wisdom to know that and source that table.” When The Velvet Underground grump asked how he should sing, Kerr asked him to just sing it as Lou Reed. “Lou said, ‘Everyone else is trying to be Lou Reed, so I may as well.’”

Reed’s vocals on This Is Your Land were recorded in three takes, and Street Fighting Years became Simple Minds’ third No.1 album. It succeeded everywhere except America, though Charlie admits: “You can’t have a seven-minute ballad about Belfast and expect the great American public to like it. When we were making Street Fighting Years, we thought, ‘We’re not really going to get America on this one, are we?’ and we weren’t really bothered, as we’ve only ever made records for us.”

That spirit continues 30 years later, as Charlie neatly sums up Simple Minds’ chemistry: “Jim’s words make sense of my music and gives it an imagery. Likewise, Jim can’t tell one note from the next and what I do is a world of wonder to him. We still amaze each other.”

Playing the long game

One of the demos Simple Minds are considering for their new album was first written in 1997. “We’ve been round the houses three or four times with this song,” confesses Jim Kerr. “We’ve kicked it into touch, swore we’d never look at it again, convinced ourselves it’s a pile of crap. Then one day, it turns up on a random playlist on your iTunes, and you go, ‘There’s that fucking terrible song again… No, hold on, this sounds great!’ Sometimes, a song just needs to find its time. I’m quite sure that’s the case with most writers who are as long in the tooth as me and Charlie.”

It’s not the first time a Simple Minds track has come out of storage: on their last album Walk Between Worlds, two songs had begun “at least 20 years previously”, according to the singer. “They’d also been wheeled out three or four times after we’d gone down the wrong road with them and come back,” he admits. “Sometimes songs are in the vaults because they’re no good, sometimes you just can’t crack it. There’s obviously something at the start of a song that excites you and, like this current idea, it just takes it popping up randomly again for you to go, ‘That’s great!’ But sometimes you get fooled, because you’ll work on it for months again, only to go, ‘Oh God, I’m bored of it again now.’ A song can be great for the first minute, but you’re kidding yourself on if you think it’s good for all four minutes. And sometimes it really is a great song that just doesn’t fit with the rest of the pack. All I can say about this current one is, I hope it doesn’t take us another 22 years to get it right!”

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.