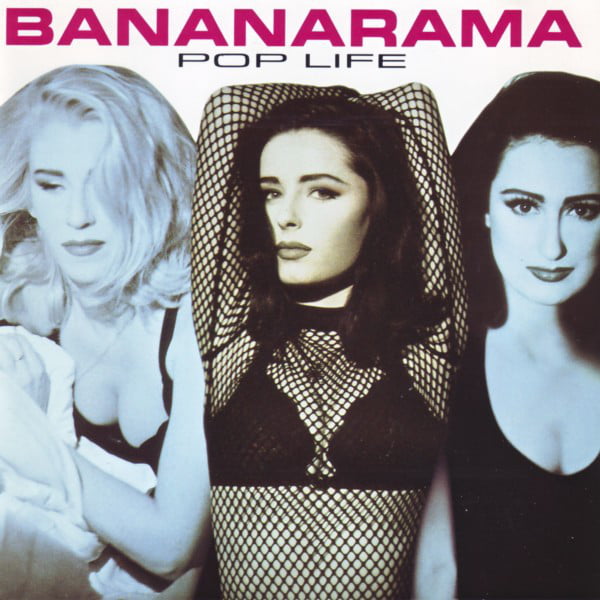

Bananarama – Pop Life

By Classic Pop | June 25, 2021

Bananarama: Pop Life was meant to be a new start for the band after the departure of Siobhan Fahey, except the group’s fifth album failed to crack the Top 40… By Jon O’Brien

It’s clear 1991 was a transitional year for the Stock Aitken Waterman elite. Kylie Minogue laid the groundwork for her mid-decade indie phase by taking more creative control on Let’s Get To It. Rick Astley made a bid for serious singer-songwriter credibility with Free. And shortly before entering his hellraising phase, Jason Donovan ventured into the rock’n’roll world of, erm, Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals.

Yet the most convincing, and unfairly overlooked, change in musical direction from the PWL stable appeared courtesy of a group in a continuous state of flux.

Bananarama’s decision to put all their eggs in the SAW basket on 1987’s Wow! had undoubtedly reaped its rewards. It’s their only album to spawn four consecutive UK Top 20 hits, reach No.1 (in Australia) and receive BRIT Awards recognition.

Making Bananarama: Pop Life

Of course, this unprecedented success also came at a cost. Disillusioned with the Hit Factory’s production line approach, Siobhan Fahey left to become the gothic foil to Marcella Detroit’s angelic soprano in Shakespears Sister.

Rather than throw in the towel, Sara Dallin and Keren Woodward instead regrouped, invited Jacquie O’Sullivan of rockabilly revivalists the Shillelagh Sisters to join the fold and, after a successful compilation and inaugural world tour, hit the studio for album number five.

However, the session results with their previous hitmakers, and Lipps Inc’s David Z, were largely deemed to be sub-par. Enter the unlikeliest of saviours.

The former bassist of post-punks Killing Joke, co-founder of IDM maestros The Orb and future producer of pretty much every other band in the post-Britpop era, Youth (aka Martin Glover) wasn’t the most obvious choice to guide Pop Life, Bananarama Version 2.0’s first, and last, LP. Nevertheless, it proved to be an inspired appointment.

“Unlike the fast pace of PWL, Youth gave us as much time as we needed to play around with ideas and fully immerse ourselves in the process,” Dallin recalled in their memoir Really Saying Something.

Play around she and Woodward certainly did (O’Sullivan’s input was confined to the vocal booth), raiding the producer’s state-of-the-art bank of samples and loops on a collection of tracks bursting with invention.

Take lead single Only Your Love, for example, which borrows from Primal Scream, The Stone Roses and The Rolling Stones, not to mention James Brown’s ubiquitous Funky Drummer, for an anthemic homage to the Madchester scene.

Its underperforming chart peak of No.27 in the summer of 1990 may have sounded alarm bells at London Records but undeterred, the girls thankfully continued to persevere with this new maximalist approach. Opening with a burst of crowd noise, Outta Sight combines skittering breakbeats with the kind of psychedelic rock riffs that

Lenny Kravitz built his career on, while Megalomaniac is an experimental six-minute whirlwind of slinky Prince-esque guitars, shimmering techno and industrial funk. Even the album’s most languorous moment, the Dubstar-meets-Ace Of Base reggae pop of What Colour R The Skies Where U Live, can’t resist throwing in sound effects of seagulls and crashing waves.

And forget their Hi-NRG take on Shocking Blue’s flower power favourite Venus. The trio’s treatment of The Doobie Brothers’ Long Train Running – which they spotted while rifling through Youth’s record collection – is even more radical.

Also boasting Sunshine On A Rainy Day hitmaker Zoë, Heaven 17 backing vocalist Carol Kenyon and Gipsy Kings (performing under pseudonym of Alma de Noche), the 70s country rock hit is revamped as a techno-flamenco banger.

Then there’s the album’s standout, Tripping On Your Love, a joyful amalgamation of acid house, hip-hop, ragga and Asian pop later remixed by everyone from Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley to none other than George Michael. The fact that it missed the Top 75 altogether must rank as one of the biggest chart injustices of the early 90s.

In fact, Pop Life as a whole was largely met with a resounding shrug by the general public, only peaking at No.42 in May 1991 (although this still remained Bananarama’s highest entry until 2019’s In Stereo).

Perhaps the new lineup had simply waited too long to make their mark – it hit shelves three years after O’Sullivan took over from Fahey, after all. Maybe the latter’s new project overshadowed her old. Or it could be that they simply succumbed to the curse of the Greatest Hits?

Read our Bananarama interview here

Bananarama themselves didn’t seem entirely confident about their new direction either, with two numbers from their abandoned sessions making the final tracklist. The watered-down house pop of Ain’t No Cure and Heartless were certainly a cut above SAW’s efforts that year for Pat And Mick and The Twins, but feels at odds with much of the other material here.

The ‘Nanas delved even further back into the past on the ethereal Is Your Love Strong Enough, with the man who worked on their first three LPs returning as producer.

Steve Jolley’s contribution fits in better with Youth’s club culture leanings, combining the group’s famously nonchalant vocals with some dreamy synths and chillout beats. Yet you still wish they’d been courageous enough to completely go for broke.

Nevertheless, Pop Life’s standing within Bananarama’s 40-year discography has only continued to grow. In the duo’s autobiography, Woodward reveals it’s one of the albums she’s most proud of.

And opener Preacher Man, their final Top 20 single until 2005’s surprise hit Move In My Direction, was the only post-Fahey track that appeared on the setlists of their triumphant reunion tour.

You can also see its everything-but-the-kitchen-sink DNA in Xenomania’s production style, particularly their work with Girls Aloud (coincidentally, Hillary Shaw – who would later take on the Popstars: The Rivals winners – left her role as Bananarama manager shortly after Pop Life’s release).

It’s slightly ironic, therefore, that Bananarama delivered their most ambitious album having just lost a member who’d felt the group were stuck in a creative rut.

Fahey might not have appreciated Wow!’s well-worn formula but she’d surely have been more accepting of a record that was bold, brave and – to reference one of Youth’s many musical endeavours – brilliant.

Check out Bananarama’s website

Read more: Bananarama Superfan – Normski