In our interview with Gary Numan, the synth-pop visionary tells Classic Pop of writing about global catastrophe during a pandemic, the struggles to sustain his career rebirth and the truth behind his attack on Spotify.

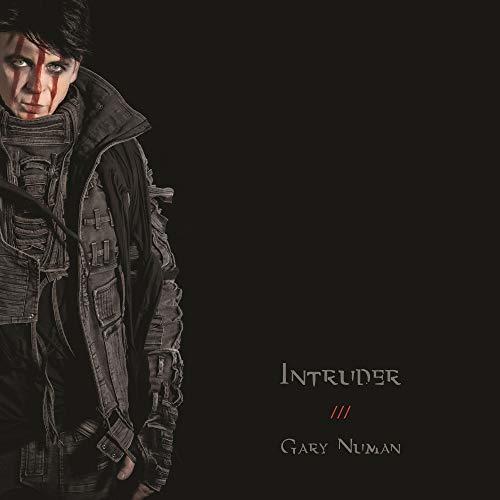

The day before Classic Pop last spoke to Gary Numan in 2019, he’d written a new song called Intruder. Numan was excited about the track, thinking it could form the basis of a companion album to the near-future climate change catastrophe imagined on 2017’s Savage.

Sure enough, Gary quickly began planning a whole LP based on the idea of Intruder, summarised by the singer as: “If the Earth could speak, what would it say and how would it feel about mankind’s treatment of it?”

That soon evolved into pondering how the planet would fight back against the ravages done to it by humanity. Then, within months, came the pandemic.

“It’s been weirdly fascinating making this album during COVID,” says Gary. “When the virus came along, it slotted straight into everything that I was already talking about, in a way that I could only say was very sad and unfortunate.”

Coronavirus specifically inspired snarling new song The Gift but, as Gary says, “There are places on the album where I hint that COVID is the first of many similar defences that Earth is planning to cleanse itself.”

Despite having seemingly prophesised the global pandemic, Gary insists he isn’t a complete soothsayer. He admits: “I was entirely convinced when I first heard about it that COVID would be like swine flu: a moment of fear that wouldn’t touch the vast majority of people, where the world could basically tick along like before.”

He’s been diligent about safety, though even someone whose music is so aware of mankind’s impact slipped up at first, confessing: “There was one guilty mistake I made.” Gary, his wife Gemma and their three teenage daughters have lived in California for nearly a decade.

When the kids were sent home from school, to mark the enforced break the Numans went to the cinema the same night. Gary recalls: “The cinema was only half-full. I thought: ‘The reason the kids are now home is because of the virus and here we are, out at the cinema, with no masks. I’m being a bit stupid here.’”

With the vaccine rollout progressing fairly smoothly, there is a chance that prolific live performer Numan can soon get back on tour, though his analogy on how he feels right now is typical of his blunt humour: “Things are getting better. But you know when you’re bursting for a wee? That last 10ft before you get to the toilet is always the worst bit. Life will get better, but not today: today still feels really shit. Financially, not touring is beginning to feel noticeable. There are worries creeping in I’ve not had for years.

“If I have to go back to the way I lived a few years ago? Fucking hell, not that again.”

That Numan is starting to sense financial worries feels cruel when he’s only recently celebrated his biggest success for decades. Savage reached No.2 in the UK, his first Top 10 album since 1982’s I, Assassin. Only Foo Fighters’ Concrete And Gold prevented Gary having his fourth No.1 album.

“When I got the call saying Savage had got to No.2, I cried like a baby for a good seven minutes,” he states simply. “I’m so focused and driven, I’m sometimes unaware of the fears lurking just underneath. Hearing that chart position flipped a switch. I didn’t even say, ‘Oh, great!’ I just went, gone: tears. There’s a huge amount of fear, worry and anxiety underneath my projects. Bizarrely, it’s only success which brings that out. You’d think Savage doing so well would be the moment of ‘Phew, brilliant!’ No, it’s terror.”

Read more: Gary Numan Superfan

Read our 2019 interview with Gary Numan

Gary’s wilderness period, what he calls “my terrible middle years of selling my soul”, has been well-documented. He’s fascinating talking about cherishing the justification that success brings, while doing everything he can to avoid deliberately chasing it.

Having achieved a No.2 album last time out, there is a worry that anything less than a No.1 would mean Intruder could be seen as a backward step from its predecessor.

“The stress I felt to make an album after Savage did so well is enormous. It doesn’t get better,” Numan acknowledges. “But it can’t be all about chart positions. It just can’t. If I’m being honest, another

Top 10 album with Intruder would be great. Two albums ago, I’d have died happy to be Top 10, and I have to remember that.”

Making Savage was the most pressure Gary has felt under to achieve success, when previous album Splinter had returned him to the Top 20 in 2013: “The first song I wrote after Splinter, Bed Of Thorns, was entirely about the pressure I felt in trying to write new music. It was lucky I found an idea about climate change!”

In fact, the initial inspiration for Intruder’s title track came from Numan’s youngest daughter, Echo. Then aged 11, the first poem she ever wrote essentially distils the album’s theme about writing from the planet’s viewpoint – it’s printed in Intruder’s artwork.

“Echo’s poem talked about how sad and hurt the planet feels,” explains Gary, as enthusiastic as any proud parent. “She’s written dozens of poems since and she’s so clever in the way she sees the world. The seed of Intruder started from there.

“I already knew that I didn’t want to move away from Savage’s core idea of climate change, because my children are still so bothered about it, as am I. I wondered what variations there were within that story of ‘What would Earth say?’ over 12 songs.” There’s a big laugh, as Gary adds: “Intruder has many spokes, but it’s one core idea. It’s a one-trick-pony idea for an album if ever there was one!”

The album ends on a bleak one-two sucker punch. First comes the optimism of Now And Forever, almost a make-up song between Earth and humanity. That’s followed by the apocalyptic The End Of Dragons, which imagines the end of mankind.

“Now And Forever was one of the last songs I wrote for the album,” Gary reveals. “But I didn’t think Intruder should end on any vaguely optimistic tone. I tend to be ridiculously optimistic. If you put a gun to my head, I’d think, ‘Nah, you don’t have any bullets in that.’ But the truth is, the planet is in a really dangerous place.”

At least the more eco-friendly Joe Biden has replaced Donald Trump as US President, which Gary accepts as cause for slight hope. He’d have preferred the younger Kamala Harris or Peter Buttigieg to become President, but says of Biden:

“He’s a good man, who’s put really good people around him in his team. Whereas Trump was a terrible man, who put even worse people around him.”

A fan of Greta Thunberg, Numan believes it’s her generation that might rescue the planet. “What Biden and the others are doing now is sticking on leaky Band Aids to cover a severe cut,” he believes.

“It might just be enough to stem the blood flow, until a real doctor turns up. If saving the planet is going to happen, it’ll come from today’s teenagers. All we can hope is enough half-hearted measures are put in place by the current lot, to give them time to activate what really needs doing. It’s difficult to be hugely optimistic but, human nature being what it is, if there’s a chance we will probably find a way.”

Read our interview with former Ultravox frontman John Foxx

Read our article on the cover art of Depeche Mode

That Gary Numan is able to ultimately strike an optimistic note about the future of mankind, even when discussing his sombre new album, is typical of a musician who’s a lot more upbeat in person than you’d expect from his persona as the ultimate dark lord of synth-pop.

Having reignited his career with the uncompromising industrial edge of 1994’s Sacrifice, Gary’s music since has been a totem of steely intent. But there’s always been empathy in his songs, too, a rallying cry for outsiders.

The honesty at the core of his lyrics is matched by how Numan conducts himself in interviews – there’s none of the guarded shield put up by many artists who’ve faced the media for as long as Gary has been famous.

That straightforward nature makes for easy sensationalism. In January, Numan made headlines when he revealed one of his songs – he didn’t say which – earned him just £37 in royalties despite notching up a million streams on Spotify.

Mention of the story is the only time Gary looks pained during our conversation. He hadn’t meant to be “courtroom accurate” in quoting the figures, as he thought it was funnier that the sheer amount of paper spat out by his printer in printing off the “pointlessly detailed royalties statement“ was worth more money than the earnings detailed on the statement in the first place.

Gary is also frustrated that his comments have since become misinterpreted, having become widened in their reporting to appear to be an attack on record companies as well as streaming services like Spotify. That has placed the singer in an invidious position: he’s on the side of the artists, but doesn’t have a particular beef against record companies.

“My comment wasn’t about record companies at all,” he sighs. “My opinion has been used as a stick to beat labels with, which is unfair. It’s put me into a position where I feel I have to defend record labels, when the truth is there’s some flexibility there, too. I’ve been dragged into an argument I didn’t want.

“I want to make it clear that I wasn’t talking about record label payments, but there’s room for improvement there and I’m very much on the artists’ side. I feel like I’m walking along a fence that gets narrower and narrower.”

In Gary’s eyes, “everyone has been fucked over by the amount streaming services pay.” He castigates the major record labels for agreeing those royalty rates with the streaming services, in return for getting equity in Spotify, Apple Music and co. “Streaming companies say they’re barely struggling along as it is on the tiny pittance they pay already, which clearly isn’t true,” he fumes.

“You’re talking a fraction of a cent per play, which is then divided among artist, label and publisher, so the artist gets a fraction of a fraction. Musicians can’t survive from streaming income, and its pro-rata system means it benefits most the artists who are already doing well, rather than artists who are struggling.”

Numan would rather see royalties go towards the artist being listened to, rather than put into a larger pot.

Given the meagre money that artists make from streaming, would Gary even consider music to be a viable career if he was starting out now? There’s no hesitation in his reply that he’d definitely try, as he points out “old-school royalty rates were pretty rubbish, too.”

In his view, there could at least in theory be advantages to making money from streaming, as he explains: “Under the old royalty system, you needed to be successful for some time before you saw any benefit, because your initial success only paid back the advance the record label gave you to make your album – an album which the label then owned anyway. The whole system was fucked from top to bottom, and now it’s only fucked in a different way.”

He continues: “Although streaming rates are unfair, while your music is up on Spotify, it’s constantly selling, even if it’s only in micro amounts. If you sell an album on CD or vinyl, the buyer can listen to it for 50 years and never pay for it again.

“In that sense, streaming is better for artists. But only if it’s fairly paid, which it isn’t. As streaming royalties are so small, you’re currently better selling a CD for a tenner.”

According to Numan, his audience has finally begun migrating from buying CDs and vinyl to listening to his music on streaming.

“My streaming income is alright now, but I couldn’t live the way I do now from streaming. If it wasn’t for songwriting publishing and live income, I’d have to make drastic changes. Where I’m lucky is that, when there isn’t a pandemic, I tour constantly. I do very well there. Also, I wrote Cars. That one song alone sees me right.”

The curtains are drawn to block out the early morning Californian sun as Gary talks to Classic Pop, but the chandelier, tasteful high-backed chairs and sleek wooden surfaces that can be glimpsed on Zoom suggest the Numan house is as classy as you’d expect from someone who’s revived his career so elegantly since those regrettable middle years.

It’s just as classy that Gary accepts the part Cars has played in his career, as he acknowledges: “If I hadn’t written Cars, I wouldn’t be living in this house. I got a snyc deal just this morning from a Swedish company to use Cars that’s worth a fortune, a mental sum of money. My life would be very different if it wasn’t for that one song and I’ve written hundreds of them. The truth is, even with a career as long as mine and with the success it’s given me, the majority of my lifestyle is from one song that did particularly well.”

Gary is aware of the irony that Cars is from The Pleasure Principle – one of three albums made inside a year, along with Tubeway Army and Replicas.

Considering the stress that following up a No.2 album now brings, how the hell was he able to be so casually prolific at the start of his career? “I think it’s because the success I’m having now is a second chance,” he considers. “Having known how low a career can get, that’s much harder to escape.

I was so much more casual and blasé at first, so I didn’t feel under any pressure. It all seemed so easy. I later learned how hard it can be, but at the time? No, it just felt simple. That’s not arrogance, just youthful stupidity!”

Gary has told us before how much he regrets his early 90s albums Outland and Machine + Soul, saying of the latter: “What a stupid title for a record that has no fucking soul at all.” Does he ever get fans who tell him those albums aren’t so bad after all?

“Yeah – bless them, they don’t know any better,” he smiles. “Look, it’s not that Machine + Soul is musically a bad record. It’s just not a good Gary Numan record, because it has very little of me in it.”

Part of Numan’s creative renaissance is also down to careful management of his career. Gary now manages himself, so he can use instinct on how far to exploit commercial opportunities alongside the spirit of the tough music that’s made him thrive for over 40 years.

But managing himself nearly cost Gary the most fruitful relationship since his creative rebirth, with his producer Ade Fenton. Numan and former dance DJ Ade have worked together since 2006’s Jagged, but fell out after Splinter, when Ade was Gary’s producer, keyboardist in his live band and co-managing his career outside North America, after Numan took on a manager for the US when he moved there in 2012.

“I was being given different information by different sides,” recalls Gary. “Little frictions started to creep in. In the end, I had to go with one camp or the other and I went with the American management. That caused grief with Ade.”

The pair didn’t speak for two years. “We didn’t thrash any of it out. It all built up, until there was a big falling out. It was all so unfortunate, as Ade was getting bad information about me, too. My wife was talking to Ade, trying to build bridges, but I was having none of it. But then Ade sent me a lovely message of sympathy when my mum died, which broke the ice. At that point, Gemma jumped in and said, ‘You should meet up and talk about what really happened.’”

The pair met at the home of Richard Beasley, drummer in Gary’s touring band. “We learned a lot about the bad information on both sides, what mistakes we’d both made.”

In the interim, Gary had tried working with other producers, largely from the practicality of needing someone new but also to see if his music could work with other creative partners.

“I had a lot of recommendations from friends, and prospective producers were sending examples of their work,” Gary remembers. “I met a few people, but there was no one I really liked. Nobody felt in tune with what I wanted to do. Once we decided to work together again on Savage, Ade became my best friend again.

“In terms of the writing, I’m on my own. But I know that, once I ready a song to a certain point, I can stop worrying about it. Ade takes my unpolished piles of embers and turns them into art. I don’t know how many albums I’ve got left in me, but I can’t imagine going anywhere else. We’re a team for the rest of my career.”

How long the rest of Gary Numan’s career lasts is a question that had begun to trouble the singer before COVID made touring impossible. Numan looks well, his raven hair matching his black T-shirt, his ready smile also part of a charm that keeps him looking younger than 62. But Gary admits: “I’d been talking to Gemma before the pandemic about carrying on for another three years and that’d be it. Another couple of albums, another couple of tours and I’d be done. And, now that I haven’t toured for 18 months, every part of me thinks: ‘Fuck that. Let’s do this forever!’

“I didn’t realise how much I love all of this until I wasn’t allowed to do it. When I tour regularly, I don’t miss it. Because I’m always planning a tour ahead, I most liked the bit in between when I’m doing normal stuff. But I really miss the excitement, the passion, being with friends and hanging out with them.”

Gemma comes on tour with her husband and Gary says: “She misses it, too. The lifestyle I’ve chosen for decades is to have periods away from the normal world to have adventures. It’s your reason for being. It’s not just financially that not touring affects me, it’s a whole chunk of my life that’s just gone. I cannot wait to get back out there.”

Cancel plans for Gary Numan’s retirement, then. He’s around for as long as he’s got – or the planet has had enough of humanity, whichever comes first.

Gary Numan’s official website

Read more: Making Ultravox’s Vienna

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.