Japan: Quiet Life – A Retrospective

By Anthony Reynolds | July 9, 2021

Japan biographer and musician Anthony Reynolds looks at the origins of Japan: Quiet Life and the latest 2021 deluxe reissue with reflections from band members and associates…

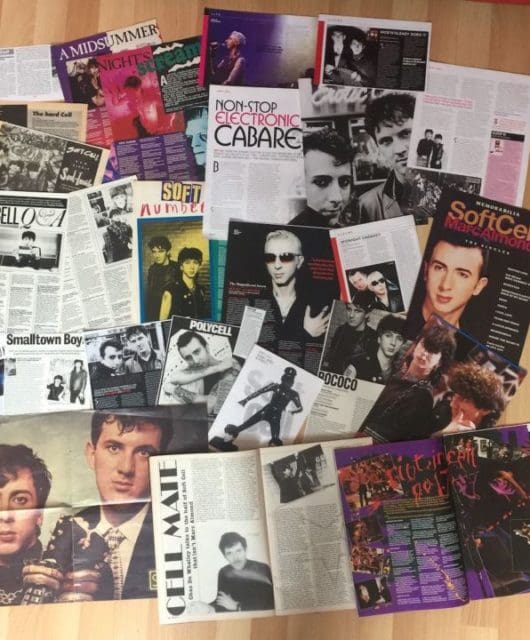

In early 1979, Mancunian teenager Stephen Holden was big on Japan.

“I’d seen them live as many times as possible,” says Holden. “From the Blue Oyster Cult support tour in June 1978 and whenever I could thereafter; St Albans, The Lyceum, Nottingham… all in the same year. I had every record, every cutting, T-shirts, fanzines, badges, posters. All signed. I had met the band backstage and in their management offices several times. I was an avid fan of the music and look.”

Stephen was in the minority. At this point in the UK, Japan, if they were considered at all, were considered an unfunny joke. In 1978 they had released two flop albums on Ariola Hansa – the raw faux pop funk of Adolescent Sex and its slightly more sophisticated, atmospheric sequel Obscure Alternatives.

A handful of unsold singles joined both albums in the bargain bins of Woolworths up and down the country. You would not hear Japan on the radio nor see them on TV.

However, they did appear regularly in the press; if only to be insulted each time. “There’s such a stench of musical decay,” wrote the NME of Adolescent Sex, “that my stylus refuses to go near it again.”

The group were seen as a glam throwback to an era recently erased by punk and new wave; perfumed, made-up fops who had the audacity to take themselves and their music seriously. And yet by the spring of 1979 things were changing.

In Europe, where the tastemakers of the NME had less authority, Japan – who after all could really play – were seen as a more seductive and intriguing prospect. Audiences and press there were more open-minded and appreciative.

More deliciously, the band were big in Japan where their looks alone attracted a massive following of almost exclusively teenage girls who bought anything with their face on. They were on TV. They were on the cover of every pop magazine. They were on lunch boxes. They were selling out the Budokan (capacity: 14,471).

Britain was still catching up and more importantly, Japan were catching up with themselves; finally becoming the band they would be remembered as. Their first two albums had reflected their love for a certain kind of Americana as expressed by Television, Patti Smith and Lou Reed while Japan themselves had barely ventured outside of London.

By the time of Quiet Life, they were well travelled. After a small US tour in 1978, America had lost its lustre for frontman David Sylvian in particular but travelling through Europe and Japan had had the opposite effect. Europe especially had aroused Sylvian’s imagination, allowing him to write from new perspectives refracted through his love of late 70s Bowie and Roxy Music.

The bridging point between the soul/funk squall of Japan’s first two albums and the cool, grey, European groove of their third had been the ‘disco rock’ of Life In Tokyo, recorded with Giorgio Moroder in Los Angeles in March 1979.

This was preceded by a self-produced, sequencer-heavy demo of European Son recorded in London the previous January. Guitars, haircuts and vocals were now turned down, sequencers, bass and synths were turned up. Sylvian was crooning rather than screeching, inviting attention rather than demanding it.

Neither …Tokyo nor European Son would feature on the forthcoming album but the new musical DNA inherent in both, would.

Yet for Holden, the Japan of Quiet Life would mark the beginning of the end: “I went to their Rainbow gig in April 1979. The curtain lifted to a half empty venue revealing their ‘new’ image; cropped, coiffed hair and more sophisticated stage outfits… initially I was horrified. Gone was the trashy rock’n’roll look that I loved.

“They started with Halloween, unreleased at that point, which was still fabulous and didn’t seem too different from the first two albums. However, it became apparent that they had rearranged the bulk of the songs from the first two albums. This was a disappointment at first. However, I grew to love the new arrangements and ‘sound’, just not as much as I did originally. That Rainbow gig was definitely a watershed moment.”

Japan would become a band known for their ‘watershed moments’. From an audience’s point of view it seemed that the band had matured, discovered sequencers and become introverted overnight. And while they had found both a new producer (Roxy’s John Punter) and a new hairdresser (The chic Mane Line of Knightsbridge) their new sound had been a more gradual metamorphosis.

Robert Dean was the band’s guitarist; a somewhat overlooked player at the time, though understandable in the light of bassist Mick Karn’s peacock-like charisma but whose playing on four of Japan’s albums has since received a welcome and positive re-evaluation.

Dean: “I think in any band there is (or should be) a logical progression from one album to another. I realise that to many Quiet Life appears as a huge jump from Obscure Alternatives but I can’t honestly say it did for us. It reflects the music that we were all listening to for inspiration at the time, which was distinctly less rock and more experimental, atmospheric and electronic.”

“It’s as if we discovered sophistication, subtlety and nuance overnight,” adds keyboardist Richard Barbieri; explaining their evolution was, in part, because “David started writing more on the piano, which produced stronger songs”.

Read more: Making Japan: Tin Drum

Read more: The Lowdown: Japan and David Sylvian

Prior to the studio sessions, Sylvian himself took the bold step of booking into a hotel with a portable keyboard in order to “…help propel me away from the band’s determinedly rock-based determination.” In other words, Erik Satie’s influence would replace that of Hall And Oates.

It’s interesting to see the list of bands Japan went to see live during the late 70s and early 80s. Nick Huckle, Japan’s friend and tour manager recalls: “Later gigs I can remember going with them as a band to: Kraftwerk, Yellow Magic Orchestra, Stevie Wonder, Iggy Pop, Nina Simone, Bruce Springsteen, X-Ray Spex.” One could feasibly recognise elements of all these groups in the ‘new’ Japan.

Japan: Quiet Life – Fall in love with me

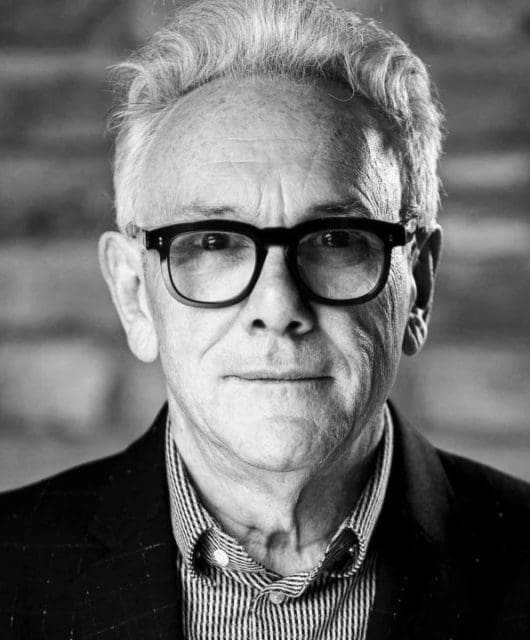

The album sessions for Quiet Life began at Basing Street Studios on 3 September 1979. New producer John Punter would play a hugely important part in Japan’s development. Other possible producers approached had been Chris Thomas, Ken Scott and Robert Fripp. Punter was able, hungry and sympathetic, and just as importantly the band liked him and he loved them.

Punter: “I remember meeting them. It was love at first sight! They looked immaculate. Their glam appearance wasn’t off-putting at all, probably because of my experience with Roxy Music. I had the same kind of feeling as when I met Roxy for the first time as I did with Japan. As people, they were close. Any hierarchy there was wasn’t as obvious as it would become. David was often stern and serious, but Mick was hilarious, a very funny guy. But despite their appearances they were very normal.”

As Japan started laying down drum and sequencer tracks, the UK singles chart offered some optimistic signs as far as Japan’s future was concerned. The Top 40 then was exquisitely varied, in the best tradition of Britain’s eclectic musical tastes and talent.

Although the No.1 spot was held by the Valium-smooth pop of Cliff Richard’s We Don’t Talk Anymore, other entries were more prescient. Both Gary Numan (Cars) and Roxy Music (Angel Eyes) were holding their own in the Top 10.

Sonically, Roxy were closer to where Japan were headed than Numan, particularly in the placing of the Roland CR-78 drum machine so high in the mix.

The Quiet Life sessions were among the happiest times the band would ever know. Each member was gaining in confidence. “By the time of Quiet Life I would say I had become indispensable. At least that’s how I liked to think of

it. And with that feeling the confidence grew and I became more creative,” explains Barbieri.

Karn sums up the importance of Punter as being a key part in their new assuredness: “We started taking it seriously when we met John. That had a profound influence on all of us, in that we were suddenly being taken seriously as individuals, as musicians, and he pulled out the best in us.

“Up until that point we were angry young men trying to prove a point and to go against everything that was current. I think all we needed was somebody to be on our side. And John, who was somebody we’d admired, gave us that confidence.”

This new confidence, in both playing and writing, is apparent throughout the album. What we hear on Quiet Life is a band barely into their twenties playing at the very edge of their already brilliant abilities. At the same time, they don’t step on each other’s toes. Every part is perfectly balanced, exquisitely placed; every song a network of gossamer threads and burnished angles. The rhythm section, in particular, rewards repeated listening and would influence many more commercially successful bands in time.

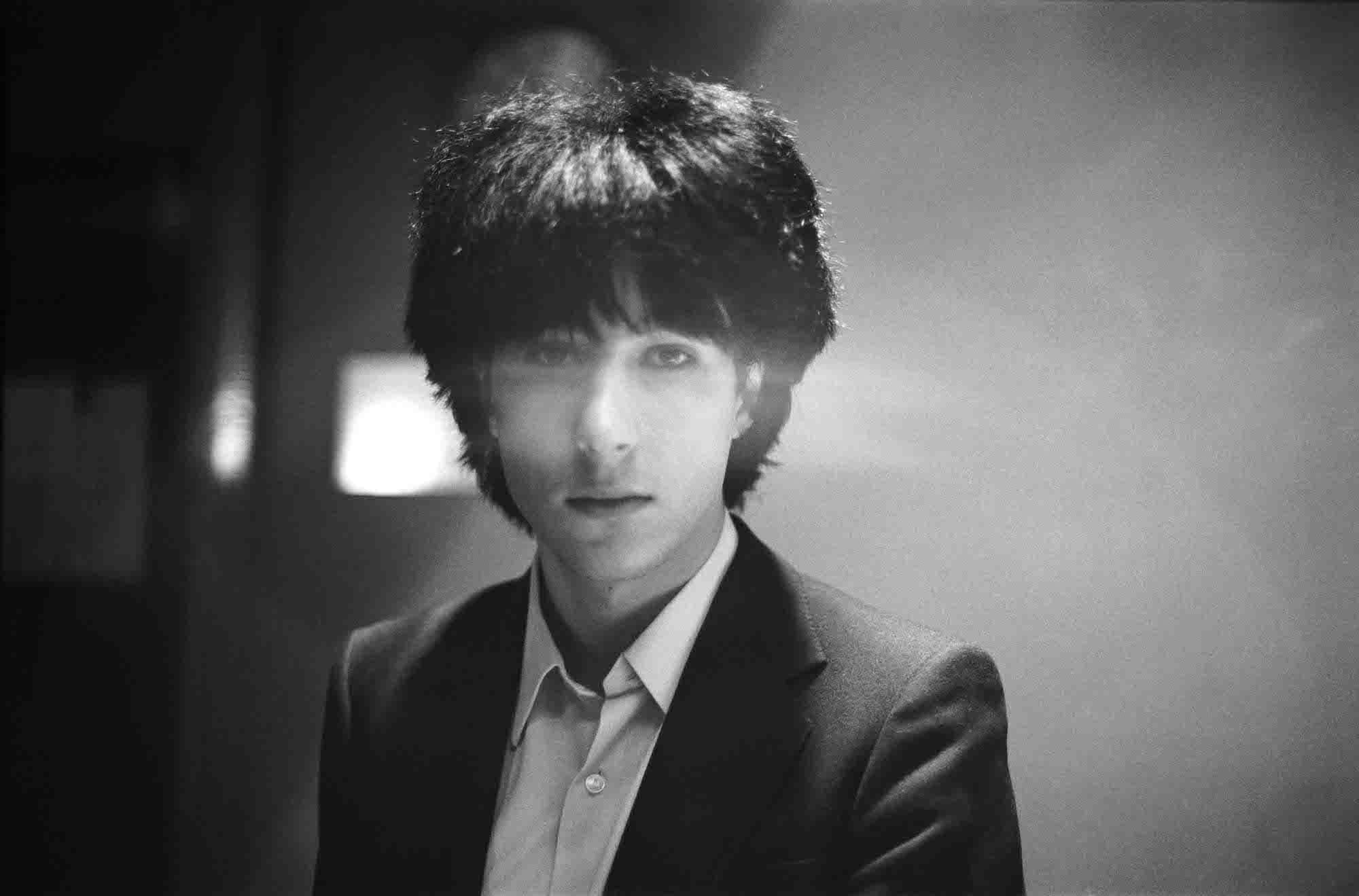

Japan: Quiet Life – Richard Barbieri. Photo by Steve Jansen

Japan: Quiet Life – Richard Barbieri. Photo by Steve Jansen

Speaking in 2020, via his episode of Desert Island Discs, Duran Duran’s Roger Taylor explained: “What a great album that was… some beautiful drum parts. Steve Jansen was an amazing drummer. A huge influence on Duran Duran.”

Duran bassist John Taylor, speaking in 2018 confided that “Mick Karn was a big influence. For me, Quiet Life was the album. On a song like In Vogue, yes, there’s what David is doing on top but actually the soul that’s coursing through the middle of it, that I really connected with, was what Mick was doing. Very soulful.”

Jansen himself is able to name some influences that informed his playing on Quiet Life: “Dennis Davis’ playing on Bowie’s Low was very inspirational. I thought the drum fills and sound was amazing. But another huge influence on me was when Jerry Marotta said in an interview that the drummers on Peter Gabriel III, (aka Melt, on which he played on Games Without Frontiers), were not allowed to use any cymbals.

“I could hear how that made drummers play certain fills to compensate for that lack of dynamic and it was really interesting and definitely an influence, particularly Phil Collins’ playing on No Self Control.”

Japan: Quiet Life – The artists of tomorrow

Japan’s ‘new’ sound was cemented by Sylvian’s nouveau riche croon and Barbieri’s atmospheric synths, where approach was more important than technique.

“While some will play 100 notes in 10 seconds,” explains Barbieri, “I prefer to play one note that lasts 10 seconds and that does something interesting in context with the track or in isolation. It’s just my instinct and not dissimilar in approach, at least, to artists like Eno, Harold Budd, Talk Talk etc, who play with space and let the sounds ‘breathe’.”

This didn’t mean, though, that there weren’t some lovely, more traditional-sounding keyboard parts on the album. Both Despair and The Other Side Of Life employed gorgeous piano motifs. Barbieri explains: “Those parts are pretty simple. Neither David nor I were particularly proficient on the piano at the time. You can do multiple takes and divide up the bass notes, chords and melody into separate overdubs…”

Read more: Japan – Gentlemen Take Polaroids

Read more: Richard Barbieri interview

Final overdubs were the addition of a 25-piece orchestra on two of the album’s most stately tracks; In Vogue and The Other Side Of Life. The latter, in particular, would come to hold a special place in Sylvian’s heart as he would still be performing it live decades later. It may also count as being one of the first Japan songs ever covered on record; it crops up on Jimi Sumén’s Between Orient And Accidents album less than two years later.

Describing the breathtaking high wire drumming on this track, Jansen is perhaps speaking generally for the band’s then attitude when he says: “The drum fills or pattern intricacies would become a test of nerve. You’ve just gotta go for it.”

The album was mastered on 5 November 1979 at Trident Studios. Packaged in a soon-to-be iconic cover by photographer Fin Costello, the image of Sylvian with two-tone haircut and lurid leather box jacket, hand pressed against glass whilst looking beautifully bored, would influence the dress sense and haircuts of tens of thousands of optimistic teenagers in years to come.

Quiet Life was, astoundingly, released mere weeks later in Canada – just ahead of two live shows there – and on 20 December in Japan. The UK release came in January 1980. Even more astonishing was that in the UK no single was taken from the album at the time.

A planned three-track single for that January, comprising Quiet Life, A Foreign Place and European Son, had been dropped in favour of a cover version of the classic Smokey Robinson track I Second That Emotion. Perhaps this lack of faith in Japan’s original material was a sign of Hansa’s growing disillusionment with their investment – the feeling was mutual.

However, the album was the first of Japan’s to chart in the UK, at No.53 while the single, (with Quiet Life buried on the B-side) flopped. Although the UK public were inexorably waking up to Japan, the press were still dismissive.

“They may seem seamlessly full-ahead European to you,” wrote Ian Penman in the NME under the pathetic title of There’s A Nasty Nip In The Air, “but it all sounds slyly studied Roxy Music Stranded to us.”

As time would tell, Hansa’s lack of faith was wrong and the poor reviews were misguided. Japan would grow musically, as people and in popularity at a brisk rate. Within two years of Quiet Life’s release the band would become massive with a legacy far outliving the relatively short time they were together.

Of course, being Japan they would split up on the cusp of what seemed like true international success, in late 1982. But that was Japan. Wilful, perverse and destined to leave a beautiful corpse; the pop equivalent of Princess Aurora in Sleeping Beauty.

Japan: Quiet Life – Editions of you

Since its initial arrival in 1979/80, Quiet Life has been released in almost 79 versions and reissued several times. Of the re-releases, the 2012 triple vinyl version put out by the Music On Vinyl label is arguably the most ambitious.

Yet that version suffered from poor remastering and a repetitive tracklisting of different versions of the same song coming immediately after one another – hello, Life In Tokyo.

When I was approached by BMG to consult on a 2021 re-release, I was asked to compile an ‘Ideal Tracklisting’ from a fan’s perspective. I opted to collate the most seldom heard remixes in chronological order while avoiding repetition.

I also went for the odd piece that had never been released on CD before: the instrumental Life In Tokyo Theme, for example, which had only appeared as a B-side to the 1982 release of Life In Tokyo but pressed at the wrong speed. BMG went with some of these suggestions.

Being a part of this process, however tertiary, allowed me a first-hand insight to the problems inherent in reissuing a group like Japan. For a ‘pop’ group, they were perversely focused, thoughtful and particular. Thus there are very few musical ‘offcuts’ available.

Japan’s original albums were beautifully composed renderings reflecting specific periods in their lives. The resultant album was an unequivocal statement and if there were any pieces from it that could be released as singles, then so be it. But Japan’s approach to their craft was hermetic. They were not big on B-sides and the songs which were committed to tape were the ‘definitive’ versions.

Unlike Duran Duran, Japan were not interested in performing extended versions of their songs live in the studio so that they could be released as “Night Versions”. That’s not to say that Japan were completely aloof to the 12″ format. After they had shifted from Hansa to Virgin in late 1980, the band began to have commercial success in the UK. Indeed their first UK Top 20 single hit was with Quiet Life in 1981.

With new Japan releases from Virgin and re-releases from Hansa both competing for the same chart, the group – powerless to block their old label – instead co-operated with them. Their then current producer Steve Nye was tasked with remixing and making the slightly “old Japan” sound more like the “new Japan” of 1982. Karn also overdubbed new sax and bass parts onto remixed versions of Life In Tokyo and European Son.

As for other ‘extras’ available, Japan rarely demoed songs, preferring instead to rehearse diligently before entering the studio – Barbieri played me the one available four-track demo from the Quiet Life sessions, Alien.

Downtempo and industrial sounding, with different lyrics, it bears no resemblance to the Alien of the finished album. Sylvian is not keen on such relics being made public. “I wish we had some outtakes and demos that could be included, but that just wasn’t the way this band operated,” confirms Dean.

And yet this 2021 re-release is surely the definitive version of Quiet Life, especially in its Deluxe incarnation. Although it features the Japan Live In Japan four-track EP recorded at the Budokan on 16 March 1980, the multi-tracks of the complete concert – recorded and mixed by John Punter – are long since lost.

In its place we get an actual audience recording of a full-length gig that has been cleaned up by Steve Jansen from the same period. Through the shrieking wails, we hear Japan flexing their musical muscles in front of a hysterical audience that are almost – but not quite – seemingly at odds with the music being played.

For a band as committed to their perfectionism as Japan, this is a thrilling insight into the reality of their live shows back then; a band who were the epitome of style and content filtered through pure oestrogen-fuelled screaming.

“I think it accurately represents what it was like to have been there,” says Jansen of the gig. “I really enjoyed listening to it because the performance is pretty solid. It really captures the excitement that’s missing from our official ‘live’ album [1983’s Oil On Canvas]. I’d rather listen to this. It’s really the first time I’ve ever listened all the whole way through to a Japan bootleg.”

Dean, too, is happy with this latest incarnation of one of his favourite Japan albums. “I think it’s an important release,” he says. “It’s an album that has generated a lot of positivity over the years and there are many other albums that have had the Deluxe treatment that are far less deserving. Hopefully, it will go further in cementing its importance not only in the band’s catalogue but generally.”

Some lifetimes ago, Sylvian said of this period: “We’re making music that will hopefully still be listened to in 10 years’ time.”

So far, it’s 40 and counting.

Check out David Sylvian’s website here

Check out Steve Jansen’s website here