Eurythmics: Annie Lennox interview

By Classic Pop | August 25, 2021

In this exclusive Eurythmics interview from 2018, we talk to Annie Lennox about her and Dave Stewart’s relationship, their music, their 40-year career and the future of their partnership… By Paul Lester

Annie Lennox – singer, songwriter, political activist and philanthropist – is talking to Classic Pop from her home in Cape Town, South Africa, where she is contemplating the Evening Of Music And Conversation at London’s Sadler’s Wells Theatre, which was due to take place on 4 March.

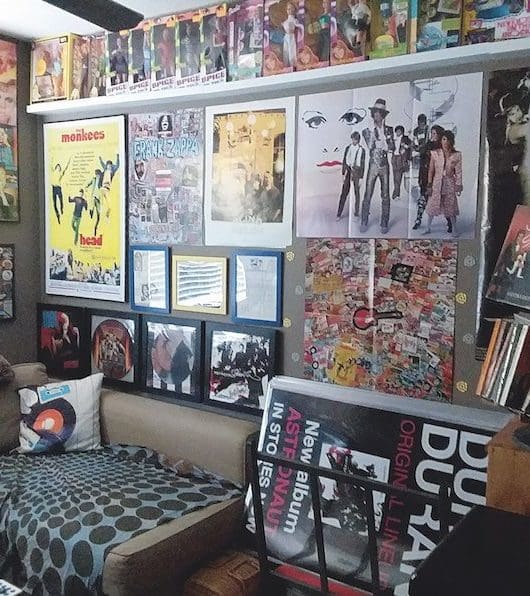

“I don’t know what the conversation will entail yet,” she says, sounding surprised, as though the idea has just occurred to her. “There will be a look through my archive. I thought it might be interesting to the audience for me to share my photographs. There’s a narrative in them, somehow.

“It will be a really interesting evening,” she adds. “For me as well, hopefully. It’s nice for me to be able to look back in time and see the shape of the journey, as it were.”

Is she okay with looking back? “Oh, of course,” she says, as Classic Pop breathes a huge sigh of relief. “I’m quite open to that.”

Eurythmics: Annie Lennox interview – Humble beginnings

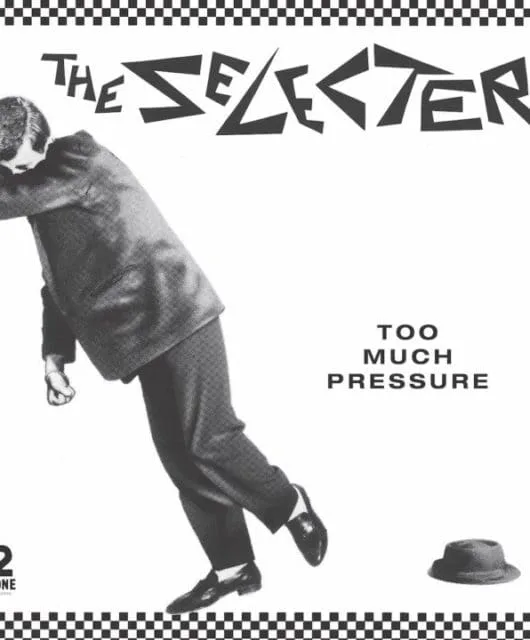

Initially called The Catch, Annie and Dave Stewart first found fame as part of The Tourists and the post-punk power poppers who released three albums and half a dozen singles between 1976-80. They had two Top 10 hits, a cover of Dusty Springfield’s I Only Want To Be With You and So Good To Be Back Home Again.

It’s 43 years since Dave Stewart walked into Pippins, the health food restaurant in Hampstead where you worked as a waitress. What are your memories of that day he arrived with his friend Paul Jacobs and scrawled “will you marry me?” on the steamed-up window?

Annie Lennox: I remember it was nighttime and the manager of the restaurant saw these two guys coming in. He was nervous because he could see they were ne’er-do-wells. I was a bit nervous, too, because I was like: “Oh god, what is he gonna think of me?”

Eurythmics: Annie Lennox interview

How soon was it before you realised this was somebody with whom you might have a musical future?

I didn’t know that. I just felt he was such a sweet soul. He would always be carrying these two plastic carrier bags with all his belongings in, and he just seemed a bit vulnerable. My heart went out to him. He was such an unusual person. We just talked and talked.

By 1977 you had the band The Catch, who morphed into The Tourists. Were you busy gig-goers? Did you see the Sex Pistols, The Clash or The Damned?

No, I never saw any of them. We were so involved in what we were doing, and the person that we lived with, Paul [Jacobs], ran a record store [Spanish Moon]. So there was never a shortage of music magazines – Melody Maker, NME – and alternative records. I remember seeing X-Ray Spex and Ian Dury, but I didn’t go to clubs and concerts. I just made music and worked to try to pay the bills.

It was a galvanising time for women in music, with the likes of Poly Styrene, The Slits, Debbie Harry, Siouxsie Sioux… Did it feel like an opportune moment for you to break through?

I mean, “-ish”, sort of. I thought of it as strange that people would say to me: ”What’s it like being a woman in music?” I was just doing what I wanted to do, which was writing songs and performing. All the women that you’ve mentioned were exceptional, and I was probably quite influenced by everybody. It was all very exciting, but I didn’t make a distinction between whether it was a woman or a man.

Eurythmics: Annie Lennox interview

Dave had been in a band called Longdancer (who were signed to Elton John’s Rocket label) with Peet Coombes, and then you three formed The Tourists. What was the thinking behind them?

Well, Peet was the main songwriter on our three albums and it was tricky because he was very prolific but not very communicative. He was much closer to Dave than he was to me, which was natural enough… I think he felt that I may have caused some kind of, not a rift, but a bit of a schism between them. He never said that, but I sensed that something maybe existed like that.

Was being in The Tourists all pop star fun and fame?

Not really. We were with a company called Mogul Records and they had a sense of what they wanted us to be, and it was very different from what we wanted, so we clashed. They wanted us to be a female singer with a bunch of backing musicians. [CP: Like Blondie?] They never said that, but that maybe was what they were thinking.

Did you meet anyone good at Top Of The Pops, which you seemed to be on a lot?

We met Madness and John Lydon. It was just people passing. It was never, like: “Here is my telephone number, let’s have a coffee.”

In the mid-70s Dave was involved in a car crash that seriously affected his lungs while financial stresses with The Tourists impacted on you. Were health issues exacerbated by tensions in the band?

We had no bad feelings towards the other members of The Tourists, it was everything we’d dealt with over the years. We’d been taken for fools by certain individuals and that was painful. Listen, The Tourists was an incredible opportunity to tour Japan, all over Europe and the US. But it was time to start afresh. We wanted a clean sheet of paper so that we could reinvent ourselves.

Eurythmics: Annie Lennox interview – The Dynamic Duo

With The Tourists handing in their passports and calling it a day in late 1980, Annie and Dave decided to go it alone with a new ‘electro soul’ direction. Their debut album In The Garden failed to chart, despite the appearance of krautrock legends Holger Czukay and Jaki Liebezeit as well as producer Conny Plank, who had previously worked with Kraftwerk among many others. You can thank Barclays bank for them making it through those tough early years…

You and Dave regrouped and formed Eurythmics. In 1981, you started recording your first album with producer Conny Plank, as well as members of Blondie, Can and DAF, even Karlheinz Stockhausen’s son [Markus]. In The Garden is an underrated work.

Oh, Conny was so special. The air was thick with experimentation. Can and all these individuals were bringing in recording gear and Conny’s mind just mopped up that kind of atmosphere. You entered the studio door and it was like you’d stepped into another landscape. We all understood each other very well, which was a fantastic feeling.

By that point, you and Dave had split up, having decided your future together was musical not romantic…

Absolutely, yes.

Was there a transitional phase where that proved difficult?

Of course. It was difficult for two people to, you know, break up and then stay together! But we felt we were more than the sum of our parts.

Eurythmics: Annie Lennox interview

Did you bring any of your classical background (studying flute, piano and harpsichord at the Royal Academy of Music in London) to bear on the music?

It was definitely in there, in terms of reference points. I had a whole jukebox of Brahms, Chopin, Beethoven, Debussy, Satie… It just took me a few years to figure out I wanted to write and sing songs. Both Dave and I have a very eclectic appreciation of music. We never thought we could only do one style of music and that’s it. I think that’s why people found it hard to pigeonhole us, because we were always changing. We were bored, usually.

When In The Garden failed to chart on its release in October 1981, you were living in penury in North London. Did you feel like giving up?

I’m a pessimistic thinker, so I’m always ready for things to fail. It’s better to think things will fail so if they then succeed it’s like a wonderful prize. In a way, In the Garden was ahead of its time because we were doing sampling before people were sampling. We wanted to take something that’s really interesting and blend it with something else. It is what everybody does now. We were just experimenting.

Late 1981 was a great period for experimental pop: Dare and Penthouse And Pavement had just come out, as had Japan’s Tin Drum, Depeche Mode’s Speak & Spell and Associates’ Fourth Drawer Down compilation. Did you feel part of any ‘scene’?

We were like, they can do their thing and we will do ours. But we loved the music and everyone you mentioned. Billy Mackenzie was extraordinary, a genius. And he was from Dundee, for god’s sake!

Eurythmics: Annie Lennox interview

Did the League et al encourage you to pursue a more electronic direction on Eurythmics’ second and third albums, Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This) and Touch (both 1983)?

Those synthesised sounds were becoming more available, you could access computers and very early prototype drum machines. The power of a synthesised bass – there was nothing like it. It was such fun, making tracks with those sounds.

The first of those albums was made on a shoestring, wasn’t it?

We were always on a cut-price budget, until we weren’t, if you know what I mean. Necessity was the mother of invention. We just had to survive. Dave was brilliant. He actually went to our local Barclays bank with a little briefcase and some of our music, and told Jeff the lovely manager: this is what we are, this is what we’re doing, can we have a bridging loan? And they gave us some money! If it hadn’t been for that, it could have been a different story. I remember making Sweet Dreams, thinking: “This is it, we’ve come to the end of the line.” It was very hard and bleak. Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This), the title, was meant to be self-deprecating. It was kind of like: “Jesus, this is tough.”

Read more: Eurythmics – Album By Album

Read more: Making Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)

What was the first glimmer of hope? A play on the radio or a review in the NME that made you think: “Phew, we’re going to be okay”?

I never thought: “Phew, we’re going to be okay…” It was usually more like: “Oh shit, we’re not going to be okay!” I think the first time we were on tour in the US, Sweet Dreams had gone to No.1 and I was having breakfast by the pool at the Sunset Marquis [hotel] and I said to our manager: “Does this mean we have some money in the bank?” And he laughed out loud and said: “Yes, you have some money in the bank.”

Did you buy a house, or a helicopter?

Most people, when they make some money, they blow it on a Rolex or something. But I come from a working-class background – I looked into my ancestry [for the BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are?] and the people were poor, they were paupers, workers on the farm. Every pound had to be scrimped and saved, so it was quite a turnaround for me, having money in the bank. It was like the first kid in the family that gets into university, do you know what I mean?

You don’t get the impression you went mad with it all.

No, I never went mad. I’m not that person. I’m very quiet. There’s a lot of bling around at the moment. I’ve noticed people like their jewels, their designer clothes, they like to show their houses. I’m uncomfortable with all of that.

Instead, you were doing grown-up things like getting married and divorced and writing songs about it all?

You call that growing up? That is not growing up.

Didn’t you use Eurythmics to express all the things that were going on behind the scenes?

It wasn’t as straightforward as that. I was definitely expressing how I was feeling, there’s no question about that, but it wasn’t like: “Oh, the thing that I’ll do is, get married and get really unhappy, then I’ll write about it, that’ll be good.” I could have done without the unhappy marriage.

Still, Eurythmics must have proven a life-saver, in a sense, as a vehicle for self-expression?

I don’t know if it was. Nothing is as simple as that. What Eurythmics became was something far bigger than me. It became out of my control and also very isolating. The whole big machinery of going on tour and performing night after night was exhausting. The other side is that everyone rubber-necks you and you’re not anonymous anymore. You spend time in hotel rooms, just waiting to do the next show. That’s why people have a lot of challenges when they come off tour, because it’s a very different way of life.

Did you go out with your shock of orange hair? Or in disguise?

I think I had quite a large hat and sunglasses collection. The funny thing I learnt is that if you do want to avoid that sort of attention, avoid eye contact. Being recognised by people who feel like they know you, but you don’t know them… People think you’re something special and project things on to you for the wrong reasons. You start to get very expert at analysing what people’s interests in you are. Sometimes it was just like: “This is nuts.”

Did you ask fellow superstars for advice? Bowie, say, or Boy George?

No, I never asked anybody for advice. I mean, I would meet people very fleetingly – I met Bowie, obviously, and I met Boy George. I could list some incredible people that I met for about three minutes. And being quite shy, I was quite star-struck by them. I met Prince backstage at a club and had to try to coax the conversation out of him. It was kind of wonderful, but odd.

Eurythmics: Annie Lennox interview – King and Queen of America

By 1985, Eurythmics were at the peak of their chart powers with Be Yourself Tonight, the best-selling album of their career which also featured guest appearances from the likes of Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin and Elvis Costello. The LP made the No.3 spot in the UK and the Top 10 in the States, ushering in enormous shows for Annie and Dave across the globe.

On Be Yourself Tonight, which featured a number of big names on some of your biggest hits, you created a sound that would work on a massive stage.

Right. I know Dave was thinking along those lines. We’d played in colleges, clubs, small theatres, and he was like: “Well, we’re gonna be playing arenas now, what sort of sound would be effective there?” Plus, he’s a great guitar player and I think he wanted to play his guitar and that was fine with me. It was like: “Okay, let’s do this. Let’s be rock.”

Read more: The Lowdown – Eurythmics

Read more: Erasure interview

Were you as comfortable with Rock Eurythmics” as you were Electro-Soul Eurythmics?

I was comfortable with both. It wasn’t pure rock anyway, it was rock with an R&B element. But it was very hard, physically, to perform. We’d be onstage for two hours, and it was all-singing, all-dancing. You’d come off in a sweat. Physically, it would make me very anxious. I never knew if I was going to be able to make it through the gig. It was a relief when I came offstage that I still had my voice. Then I got nodules and we couldn’t perform for a while, which was really disappointing.

How far removed were you from the fearsome character we remember from the classic Eurythmics videos?

It’s kind of a persona – a bit like acting. With acting, though, you have a script and a character but, in the performance, you are that character. But it’s not like I go around being dramatic, and certainly not these days. The less drama I have in my life, the better. I’m a real peace and love character now! I wasn’t so much then. I felt angry and I carried a rage around with me.

Where did that come from?

Oh, lots of different things. The way women are dealt with by men. A lot of our songs are about misfortune, or pain, or rejection. They’re a lot to do with male-female relationships, and I was angry. I was disappointed, and I think that comes through.

It’s there in the titles of the next two albums: the even rockier Revenge (1986), and the return-to-electronics Savage (1987)…

Yes, that’s right, but like I said earlier, it’s not as though I got married and wrote songs [about it]. I always thought of the songs as universal, not specifically about me, even though there were some specific things.

Savage has been reappraised recently. Have you noticed?

It’s weird how people are picking up on Savage now. One journalist wrote this wonderful piece about it, how it was a masterpiece, and how people never recognised it as the most extraordinary piece of music of its time, and it was like: “Wow, no one saw that.” It’s certainly our darkest record – that and 1984 [Eurythmics’ soundtrack to the Michael Radford movie, Nineteen Eighty-Four]. They’re the two albums that I feel very connected with.

We Too Are One (1989) details the deterioration of your relationship with Dave, to an extent, doesn’t it?

I don’t think the album was about that but I think it was being created while we were struggling. We were struggling to create music. We were struggling to be in the same room. We needed to get away from each other. It’s like a marriage that doesn’t work anymore. It was so hard. It was like, I would really rather not be here and [for us to] be as far away from each other as possible. We both still cared for each other, so it’s tricky. But [the stressful situation] went on for a long time and I was relieved [when Eurythmics went on hiatus]. I’m sure he was, too.

Eurythmics interview – Going Solo and a surprise reunion

Although no formal split was announced, tensions between Lennox and Stewart meant that the band went on indefinite hiatus in 1990. Annie went on to huge solo success, releasing the albums Diva in 1992 and Medusa three years later.

The success of your solo albums must have been affirming?

It made me feel like my own person, my own artist, and that I could do things in an autonomous way. That was very important because it did give me a sense of who I was and that I did have value on my own.

And then you reunited for (1999’s) Peace. Was that prompted by the death of Peet Coombes?

That was a horrible thing to happen, but no, it had nothing to do with Peet’s death. I’d been focused on my solo career and my children, but I got together with Dave, we went into a studio somewhere for fun and we ended up making a record… I think Dave probably manipulated me and I fell for it. Something like that. There are some great songs on there. I really love 17 Again and I Saved The World Today. I like melancholic music, it’s beautiful – that’s why I love the Associates and the Blue Nile. Bowie, too, has that kind of haunted beauty.

Is that something that runs throughout your work?

Yeah, definitely. And there’s a weird dark humour. It’s almost like a private running joke between the two of us.

Could you face doing it again?

As much as I love Dave – and I truly do – I don’t know that I want to… it opens up a whole bunch of stuff. I’ve got so used to having the freedom to just do and not do what I want. I’m very spoiled in that way. It’s really important for me to do things for myself, and not have to refer to another. When Dave and I were making things back then, we had that very deep connection and understanding, but we’ve both lived lives since then. I’m not sure it could work. It could, but I’m not sure I want it to.

Still, with Eurythmics’ catalogue (on vinyl) being reissued, it must have afforded you

the opportunity to reassess?

It’s a beautiful body of work, and in some ways it has been undervalued. I think it would be interesting for a younger generation to be introduced to it. Some of the albums, like Savage, are being reevaluated as great examples of what you can achieve in pop. You can do extreme things – surreal and emotional, abstract and avant-garde – in the name of pop music.

Check out Eurythmics’ website