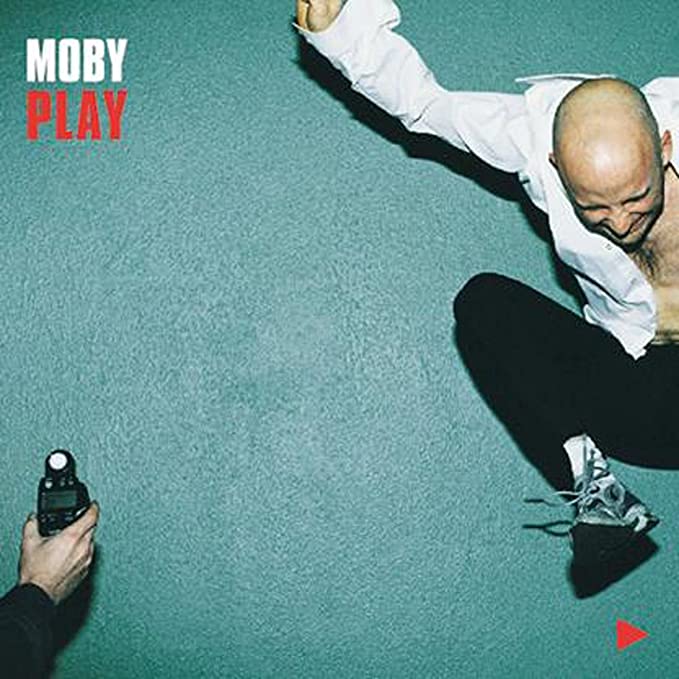

Making Moby: Play

By Steve O'Brien | August 18, 2021

With Moby: Play, the dance wunderkind finally produced an album that made him a superstar…

It seems impossible to believe now, but when Moby’s fifth album hit the shelves on 17 May 1999, the record-buying public responded with one big shrug. But then few people, not even Moby himself, expected much of Play.

Just three years before, the man born Richard Melville Hall had released Animal Rights, a blistering, full-assault punk record that was so violently off-brand it earned the one-time techno wunderkind the most dismal reviews of his career. Worst still, nobody bought it. So what chance, he reasoned, would any follow-up stand?

“I was opening for Soundgarden and getting shit thrown at me every night onstage,” Moby would recall of this bleak time in his career. When it came to setting out on his own tour, he found himself playing to crowds of 50 or under.

Despite Animal Rights attracting a few famous fans (he recalls receiving a letter from Terence Trent D’Arby and taking a phone call from Axl Rose, both raving about the album), Moby found its commercial and critical failure so crushing that he decided he was going to quit music and go back to college to study architecture. But before he did that, he was going to have one last throw of the dice, one final long-player before he gave up the music game for good.

The origins of Play can be traced to the day when a friend of Moby’s, Dimitri Ehrlich, loaned him a 4CD boxset titled Sounds Of The South: A Musical Journey From The Georgia Sea Islands To The Mississippi Delta, a collection of vintage field recordings made by American ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax.

Moby was seduced by the record’s raw, unvarnished beauty, so much so that he utilised several of its tracks as the foundation for Play. Moby’s new record would fuse those distant, faraway vocals with contemporary, electronic rhythms, marrying the 1920s and 30s to the dawn of the coming millennium.

Read more: Scritti Politti’s Green Gartside interview

Not that the album was put together on the most cutting edge tech. It was produced on mostly second-hand equipment at Moby’s Mott Street home studio in Manhattan, New York from August 1997 through 1998.

“All together, I worked on it for a year,” the musician told Chaos Control back in 1999. “I mixed it here, then I wasn’t happy with it, then I went to one outside studio to mix it, went to another outside studio, and then I ended up coming back here and doing the mixing myself. So I wasted a lot of time and money.”

Though generally happy with the final mix, Moby was still gloomy about the record’s commercial prospects. Before Play, his biggest-selling album had been 1995’s Everything Is Wrong, which had notched up sales of 250,000. Sitting on the grass in Sara Delano Roosevelt Park on NYC’s Lower East Side, he thought to himself, “When this record comes out, it will be the end of my career.”

It seemed most of the major record labels were in agreement. He shopped Play around all the big names, from Warner Bros to Sony to RCA, and it was a fat “no” from all of them.

Eventually the album was picked up by Richard Branson’s then-new V2 label, but with such little enthusiasm that Moby was forced to send review copies of Play out himself in order to secure those vital column inches in newspapers and magazines.

If press interest in Moby was low, public interest was even lower – so much so that the first show the musician was booked for to promote the album took place in the basement of Union Square’s Virgin Megastore. “Literally playing music while people were waiting in line buying CDs,” he recalled forlornly. “Maybe 40 people came.”

The album’s release on 17 May 1999 was as underwhelming as expected. The album failed to chart at all in America, and in Britain – a country that had always embraced Moby more than his homeland – it debuted at No.33. That none of the tracks were being playlisted on radio stations or on MTV wasn’t helping. But there was interest from one corner of the media.

Today, what people often recall of Play is that it was the first example of an album where every one of its tracks was licensed out to advertisers. But this wasn’t some cynical, money-grabbing ploy on Moby’s part, instead being an act of desperation. He just wanted his music out there. “[The adverts] enabled people to hear the music because otherwise the record wasn’t being heard,” he explained.

Miraculously, the strategy worked, and gradually those songs, through their sudden ubiquity, began to be spun on radio and on music TV. In January 2000, Play re-entered the UK Album Chart, and would slowly climb, over the next three months, to the No.1 spot, spending five weeks there.

At this time, Moby had been opening for second division rockers Bush on an MTV Campus Invasion Tour, recalling that “it was degrading for the most part – their audience had less than no interest in me.” Then, in early 2000, Moby’s manager called to tell him that his record was No.1 in Britain.

“I was like, ‘But the record came out 10 months ago!’” he recalls exclaiming.

“That’s when I knew, all of a sudden, that things were different. Then it was No.1 in France, in Australia, in Germany – it just kept piling on. The week Play was released, it sold, worldwide, around 6,000 copies. Eleven months after Play was released, it was selling 150,000 copies a week.

“I was on tour constantly, drunk pretty much the entire time, and it was just a blur. And then, all of a sudden, movie stars started coming to my concerts and I started getting invited to fancy parties and suddenly the journalists who wouldn’t return my publicist’s calls were talking about doing cover stories… it was just a really odd phenomenon.”

In the States, Play would peak at No.38, but that apparently lowly placing disguises the fact that it shifted over two million copies in the US in 2000. By October, Play had achieved platinum status in 17 countries, hitting No.1 in seven. And with the success of the album came singles success, with eight of Play’s songs being spun off on 45 and six of those going Top 40 in the UK.

Play’s biggest hit would be Porcelain, a blissed-out post-club classic which, unusually for the album, featured lead vocals from Moby himself. It would reach No.5 in the UK, helped, no doubt, by its inclusion on the soundtrack to Danny Boyle’s Generation X-defining drama The Beach. Surprisingly, however, it was a song that very nearly wasn’t tracklisted on the album at all.

“When I first recorded it, I didn’t think it was very good,” Moby explained to BBC Radio 2. “I recorded it, I mixed it, it didn’t really have a chorus, and I was going to leave it off the album. At the time I had a few different managers, and all three of them really liked Porcelain. So I kind of included it as a favour to them.”

By the end of 2000, those 18 songs seemed like they were everywhere. While the punchy party anthems from the likes of Fatboy Slim, The Prodigy and The Chemical Brothers were tyrannising the charts at that time, nothing else sounded like Play. Its sensual, melancholic sounds made it the perfect come-down album.

But it wasn’t just the e-heads who took Play to their bosom at the start of the new millennium – there was barely a middle-class dinner party that wasn’t being soundtracked to its tunes. It was an album that was cherished as much by people who had never picked up a dance record in their lives as by the saucer-eyed techno kids.

Questioned on why Play seemed to speak to such a diverse range of people, Moby speculated that it’s “because there’s a vulnerable, emotional quality to a lot of the music. And it was released at a time when there was not a lot of vulnerable emotion in music… I made this record in my bedroom, with broken equipment, after my mum died; so I think there was an inherent vulnerability in every aspect of the creation.”

While Play was, for the most part, critically lovebombed, the praise wasn’t unanimous. Some blasted Moby for “cultural appropriation” of its many, mostly African-American samples, arguing that the album was, in effect, whitewashing the blues.

Others suggested that Play was giving fresh life to archival recordings, which otherwise might have been lost to time. Certainly many more people have got to hear the soulful vocals of the late Bessie Jones through Moby’s sampling of her on Honey than ever did in her lifetime.

Play’s popularity has only swelled in the 20-plus years since its release. Adele has claimed it was a hefty influence on her 2015 album, 25 (“There’s something that I find really holy about that Play album,” she told Rolling Stone), while the media was awash in 2019 with celebratory 20th anniversary features. For comparison, even the bestselling album of 1999 – Backstreet Boys’ Millennium – didn’t inspire as many starry-eyed retrospectives.

There were albums that sold better in 1999 and 2000 and albums that were better reviewed in 1999 and 2000. but no other soundtracks that period like Play. As an album that sonically bridged the past and the present, it seems only right that its success crossed the end of one millennium and the birth of a new one. It may not be Moby’s favourite of his own albums, but it’s the one he’ll be forever remembered for.

Read more: Sigue Sigue Sputnik interview

Moby: Play – The Songs

Honey

The first single to be released from Play, Honey sampled vocals from folk/gospel singer Bessie Jones’ 1960 a cappella track Sometimes and a piano riff pilfered from Joe Cocker’s 1972 song Woman To Woman. Moby has admitted that this one took just 10 minutes to write.

Find My Baby

A simple track in that it’s mainly Moby playing slide guitar over a vocal sample, in this case Joe Lee‘s Rock by Boy Blue, alongside hip-hop drums. Many would have known this one from its use in an American Express ad, which featured Tiger Woods playing golf in New York City.

Porcelain

Moby takes the mic for this track and the album’s sixth single. Speaking to Billboard about its lyrics, he explained, “I was involved with this really, really wonderful woman, and I loved her very much. But I knew deep in my heart of hearts that we had no business being romantically involved. So, it’s sort of about being in love with someone but knowing you shouldn’t be with them.”

Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad?

Originally penned by Moby in 1992, a version which he described as “really bad, mediocre, generic techno”, Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad? would see the light of day seven years later, with samples from The Banks Brothers’ 1963 song He’ll Roll Your Burdens Away, and Moby giving the track a more “mournful and romantic” quality.

South Side

Initially recorded with No Doubt’s Gwen Stefani, it’s said that production problems forced Moby to scrub Stefani’s vocals from the final mix on Play. They were later restored for the song’s single release, but it remains Moby’s least favourite song off the album: “I just don’t think it’s all that interesting,” he states.

Rushing

From Moby’s least favourite to one of his favourite Play tracks. “I remember when I was listening to the demos of the album, Rushing was the only song I felt confident about,” he told Rolling Stone. “And I really didn’t change it much from the demo to the finished version.”

Bodyrock

Moby has recalled that his managers pressured him to leave Bodyrock off the album, claiming they believed it sounded like a Fatboy Slim ripoff. With a guitar inspired by Gang Of Four’s What We All Want and a sample from Spoonie Gee’s Love Rap, it’s arguably the most hip-hop-influenced track on the record.

Natural Blues

Built around vocals sampled from a 1937 recording of the song Trouble So Hard by American folk singer Vera Hall (1902-1964), Natural Blues nearly didn’t make it onto Play after a group of friends told Moby it was “too weird”. It clearly wasn’t, as it eventually peaked at No.11 in the UK singles chart.

Machete

Harder-edged than most of the tracks off Play, Machete features a Moby vocal and was reportedly influenced by electronic music outfits Meat Beat Manifesto, Frontline Assembly and Skinny Puppy.

7

Annoyingly not placed as track seven on the record, 7 is just 62 seconds long and, despite Moby’s declared love of it, is a bit of a throwaway.

Run On

Including samples from a 1949 recording of the folk song Run On For A Long Time by Bill Landford And The Landfordairs, Run On was released as the second single off Play and was apparently a headache to produce. “It was really hard to put together, because it has so many samples in it,” Moby recalled. “I didn’t use computers at this point, it was all done with stand-alone samplers. When it was finished, I collapsed in exhaustion.”

Down Slow

A dark, DJ Shadow-like instrumental, Down Slow lasts just one minute 35 seconds and is another of Moby’s favourites.

If Things Were Perfect

Named in homage to a James B-side that Moby liked and lyrically inspired by its composer walking around New York’s Chinatown, If Things Were Perfect has Moby performing a spoken-word vocal over a seductive bass riff.

Everloving

Amazingly, the version of Everloving heard on the album is actually the original cassette-recorded demo. Moby says he could never get the studio version to where he wanted it to be, so chose to use the demo instead. “It’s been in a couple really big movies,” Moby recalled. “And every time I hear it in a huge movie, I think to myself, “‘This is just a crummy demo on cassette.’”

Inside

More in keeping with the ethereal, ambient leanings of the album’s big hits rather than its other instrumentals, Moby has said in interview that he feels like he’s in a ‘K-hole’ whenever he puts on this woozy, narcotic-evoking track.

Guitar Flute & String

Moby has called this one his favourite song on Play. Like Everloving, the version from the album was recorded as a cassette demo. Though it was always a favourite of Moby’s he didn’t think anyone else would dig it, hence its placing 16 tracks in.

The Sky Is Broken

Made up of drum samples (from Creedence Clearwater Revival’s 1970 B-side Long As I Can See the Light), spoken-word vocals from Moby and played on an Oberheim Matrix 1000 synth, The Sky Is Broken is simple, but effective.

My Weakness

A highlight from the album, My Weakness is, as Moby describes it, “equal parts disconcerting and beautiful”. Reminiscent of Angelo Badalamenti’s work for Twin Peaks, it features a sample loop of an African choir, though Moby claims not to remember where it came from. The song was later featured heavily in the X-Files episode All Things.

Enjoy our feature on Moby: Play? Then get Classic Pop’s special on 90s dance

Check out Moby’s official website

Steve O'Brien

Steve O’Brien is a writer who specialises in music, film and TV. He has written for magazines and websites such as SFX, The Guardian, Radio Times, Esquire, The New Statesman, Digital Spy, Empire, Yours Retro, The New Statesman and MusicRadar. He’s written books about Doctor Who and Buffy The Vampire Slayer and has even featured on a BBC4 documentary about Bergerac. Apart from his work on Classic Pop, he also edits CP’s sister magazine, Vintage Rock Presents.www.steveobrienwriter.com