The Stock Aitken Waterman Story

By Matthew Lindsay | August 25, 2021

In this history of the hitmaking trio behind Kylie, Jason and Mel And Kim, we tell the Stock Aitken Waterman story…

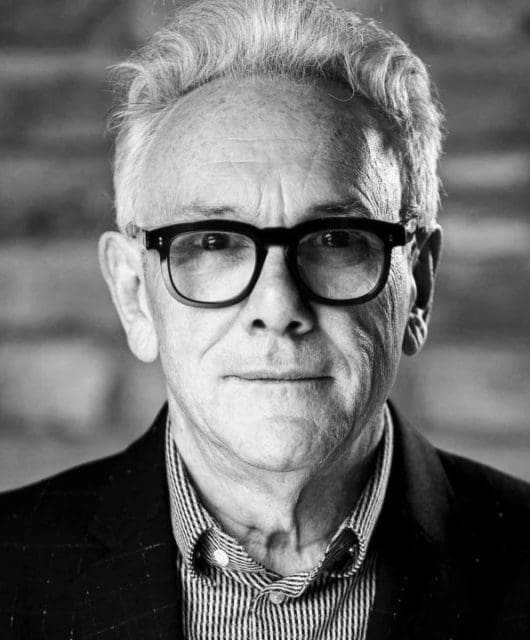

By 1984, Pete Waterman was already something of a pop Zelig. Back in the 1960s he’d witnessed the birth of Northern Soul’s sweat-soaked euphoria at Manchester’s Twisted Wheel and had trained as a Mecca ballroom DJ, an apprenticeship that also involved toilet cleaning (both spiel-master and no-nonsense grafter, Waterman had at one time been a coal-miner, too).

Throughout the 70s he worked in music publishing and in A&R at labels including Magnet Records, the home of Alvin Stardust and Silver Convention.

Not everything worked out, and disillusionment set in late in the decade when The Specials slipped from his managerial grip. But he soon bounced back, lured into the music business once more by an alliance with Pete Collins known as Loose End Productions. Loose End managed to score hits with Tracey Ullman, The Belle Stars and Musical Youth.

During the recording of Musical Youth’s second album, however, tensions arose between Waterman and Collins, and Pete next found himself ensconced in the offices of Dave Robinson of Stiff Records fame… and it was here that Waterman’s most important musical venture lifted off when Mike Stock and Matt Aitken walked through his door.

The two songwriters declared themselves very ready to ditch the cruise-ship circuit, where they had been working under the name of Mirage, and to top the charts instead.

Stock and Waterman’s paths had in fact crossed once before. In 1980, a band called Mr Gentle recorded Mike Stock’s co-composition 1-9 For A Lady Breaker. Two years later, Stock recorded the tune himself and released it under the name of ‘Chris Britton’ on Waterman’s label.

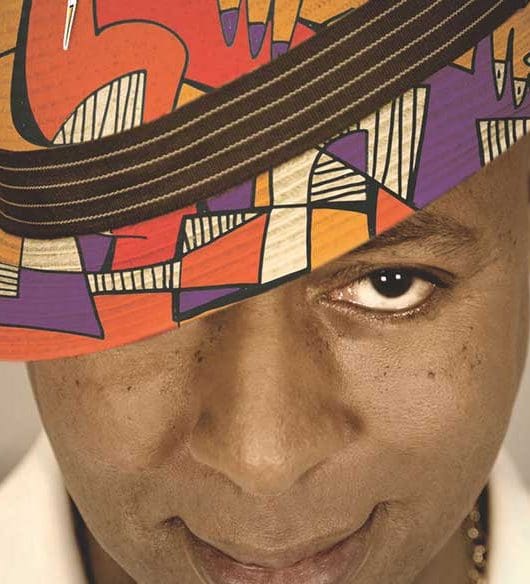

Pete’s damning verdict on this first-ever collaboration (“the worst record I ever made”) didn’t stop him joining forces with Stock and Aitken – and it would be Waterman’s recent work with Lamont Dozier, one third of Motown’s legendary Holland/Dozier/Holland songwriting team, that indicated what Stock Aitken Waterman were heading towards: a home-grown alternative to Motor City’s hit-making machine.

Their first release that year, The Upstroke, based on a fictitious Sloane Ranger dance and recorded by a sister act called Agents Aren’t Aeroplanes, failed to ignite the charts. In both its sleeve and its sound, The Upstroke offered a female twist on Frankie’s mega-hit Relax.

Airplay was scarce, though John Peel gave it a spin, exposure that would seem ironic over subsequent years. An early part of the team, songwriter/keyboard player Pete Ware, soon left, replaced by programmer Mike Gill.

The Stock Aitken Waterman Story – The Upstroke

Run by a British Greek Cypriot named Barry Evangeli, Proto Records provided SAW with all their early work, and Waterman relocated to their small offices. Early SAW products stylised their names as film credits, a Waterman whim that was quickly ditched – but the actual division of labour within the trio was unclear, and would become a source of tension over the years.

Compositions and productions would be credited to all three, but the reality was that Stock and Aitken were the musical element while Waterman took care of business. This was complicated, however, by the fact that Waterman played an integral creative role.

“Was Pete a songwriter in the conventional sense? No, he wasn’t. But he fed Mike and Matt records he’d hear, ideas and titles that created the songs,” says David Howells, PWL’s Managing Director. “Without him, those records wouldn’t have been made.”

Stock and Aitken’s early objective was to take Hi-NRG and overlay it with, in Stock’s words, “pop song constructions” (see Mixing Things Up, page 16). Their first Top 20 hit arrived in the summer of 1984 via American drag queen Divine. You Think You’re A Man wasn’t a SAW original – ex-Modern Romance’s Geoff Deane was the composer – but it showed their knack of maximising the hook potential of another writer’s song.

Hazell Dean’s Whatever I Do (Wherever I Go), came from their own pen and soared to No.4, two places higher than her breakthrough Searchin’. It was based on an earlier song, Dance Your Love Away, and since Dean disliked the chorus, Stock and Aitken rewrote the song at her behest.

The Stock Aitken Waterman Story – You Think You’re A Man

Stuttering beats, bum-wiggling bass, machine-made handclaps and cowbells provided the SAW sonic backdrop of 1984… just listen to Divine’s flop follow-up I’m So Beautiful and Girl Talk’s Can The Rhythm.

Their Cyprus Euro entry that year, Andy Paul’s Anna Maria Lena, credited to Paul at the time but actually a Stock/Aitken original, showed another side to SAW: a world away from dry ice and poppers, its sugary-sweet, pizzicato-inflected balladry was firmly implanted in the middle of the road, hinting at things to come… such as their 1984 B-side for Edwina Laurie, Tangle Of Emotions.

Early recordings were done at Mike Stock’s home studio in Abbey Wood, South London, then mixing was completed at Soho’s Marquee Studios, often by Phil Harding, who had become an essential member of the team. Harding had previously engineered and mixed The Clash, Killing Joke and Amii Stewart’s Knock On Wood, and his working relationship with Waterman stretched back to 1977.

The Stock Aitken Waterman Story – The Art Of Spin

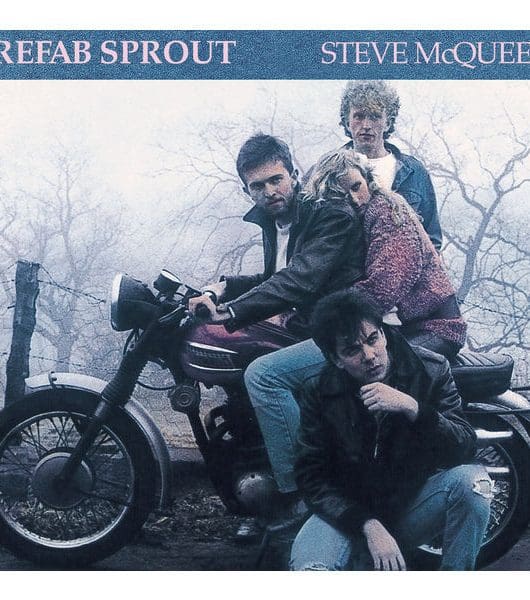

From the very start, one SAW hit led to another. The Dean and Divine records caught the ear of Dead Or Alive’s Pete Burns, and despite Epic’s misgivings (“music for queers” the label reportedly told him), SAW were enlisted to work on Youthquake.

“It was a big break for them, an act on a major label,” says Harding. They may not quite have come to fisticuffs but these were tense sessions, according to Harding, as Stock and Aitken replaced band members with samples and programmed sounds, aided by an ever-growing arsenal of technology; Fairlights/PPG Wave synths and LinnDrums (which would get an actual drum player’s credit on SAW releases).

Harding claims that Waterman watched Trevor Horn so closely that he would strike a deal with equipment suppliers to furnish him with whatever state-of-the-art gadgetry Horn had.

One song that Waterman had earmarked for a likely hit, You Spin Me Round, culminated in a 36-hour mixing marathon. The painstaking process paid off, and by March 1985, Dead Or Alive’s single completed a slow, long climb to the top spot.

The Stock Aitken Waterman Story – You Spin Me Round

Despite ongoing financial woes, a hit-making empire was taking shape. Waterman’s relationship with Proto soured, as did Hazell Dean’s; she felt they’d doomed her SAW-produced Heart First album with poor promotion, and as it turned out Proto folded in 1986.

Stock, keen for SAW to maintain independence, persuaded Waterman that they needed their own studio complex. Located in Vine Yard, a cul-de-sac behind Borough tube station, it was a former power station with thick walls, perfect for sound-proof recording (Waterman liked to hear tracks at deafening settings, a volume that gained the nickname ‘Waterlevel’).

A fortress with metal-lined doors, the facility where Waterman slept in the vocal booth for a time mixed cutting-edge technology (SSL mixing desks, AMS/Calrec mics, again always credited) with toyshop décor, reflecting Waterman’s non-musical passions of railway engines and model aeroplanes.

Soon they’d be joined by a multitude of gold and platinum discs on the walls (“putting your money where your wallpaper should be”, quipped one TV commentator). By then, they would be dubbed The Hit Factory for their ability to churn out chart smashes with mechanical regularity.

The Stock Aitken Waterman Story – Looking For No.1

At first, there were a few ill-fated projects. An album by Tom Watkins’ act Spelt Like This was shelved after single Contract Of The Heart stalled at No.91 (only Harding would work with future Watkins acts, producing Pet Shop Boy and remixing Bros).

In 1986, the group Brilliant, featuring Killing Joke’s Youth and future KLF member Jimmy Cauty, managed to get their SAW album Kiss The Lips Of Life released, but it languished at No.58 despite critical praise for their cover of It’s A Man’s Man’s Man’s World. Waterman was blunt: “F*** critical acclaim, it doesn’t pay the rent!”

By now the idea of working with other writers’ (often substandard) material was increasingly undesirable, so SAW wrote their next hit. Brilliant’s backing singer Desiree Heslop, aka Princess, took Say I’m Your Number One to No.7 in August 1985.

A move away from Hi-NRG, the track owed more to current US soul offerings; it’s interesting to compare it to Jam/Lewis SOS Band productions such as Weekend Girl. Helping them create this funkier sound were various synth players, including Andy Stennett of Freeez. “He could always get stunning bass lines from a Yamaha DX7,” praised Harding.

The Stock Aitken Waterman Story – Say I’m Your Number One

Throughout 1985 SAW composition/production work consisted largely in this vein of neon-lit electro-R&B. None of them matched the commercial success of Say I’m Your Number One, but The Three Degrees’ The Heaven I Need, Haywood’s Getting Closer and O’Chi Brown’s original Whenever You Need Somebody showcased an oft-overlooked sophisticated streak in SAW.

Harding believes their lack of consistent success in this genre was their inability to compete in the US market.

All the same, SAW knew how to tap into pop’s endless echo chamber. Waterman would play Stock and Aitken current club records he’d heard in nightspots, at the record shop he worked at or on his Liverpool radio show, but even without Pete the pair already had an encyclopedic knowledge of chart hits which they applied to creating their own.

Read more: The stories behind Stock Aitken Waterman

Read more: Whatever Happened To The Reynolds Girls?

Cheeky nods towards other artists and genres abounded throughout their material, whether it be Italo disco (Aitken cited Taffy’s I Love My Radio as a SAW favourite), Colonel Abraham’s Trapped (famously quoted on Rick Astley’s Never Gonna Give You Up) or Madonna (Into The Groove’s bassline for Kylie’s I Should Be So Lucky).

Despite the soul excursions, Bananarama brought SAW back to Hi-NRG in 1986 with a Shocking Blue cover, Venus, topping the US charts and making the UK Top 10. It was Siobhan Fahey, seduced by You Spin Me Round, who’d suggested SAW to the group after they’d suffered a series of flops.

Stock claims Dead Or Alive was always the template for Venus, but Harding says a version was attempted before Siobhan expressed what they really wanted. Fiercely independent, with – as Malcolm McLaren quipped – “bits of punk attached to them”, Bananarama began a fruitful, if combative relationship with SAW. They even co-wrote, with Siobhan’s notebook providing the title for the following year’s I Heard A Rumour.

The Stock Aitken Waterman Story – Venus

Equally feisty were Mel & Kim, two street-smart Hackney-born sisters who joined in 1986. Their debut single System was already in the can when a tape given to SAW by London Records/Bananarama’s A&R man Pete Tong suggested a far more “suitable set of musical clothes” for the sisters’ first release. System was shelved and the Chicago House strut of Showing Out became a Top 5 hit in its place.

Once again, cutting-edge dance was deftly put in a pop context. Showing Out, distilling the duo’s exuberant essence, also displayed SAW’s growing ability to ‘channel’ the artists they were writing for.

By early 1987, Mel & Kim were No.1 with Respectable – lyrically partly a defiant riposte to the tabloids for digging up Mel’s glamour-modelling past, with that “tay-tay-tay” vocal hook manipulated by SAW’s latest box of tricks, the Publison pitch-shifting sampler.

The Stock Aitken Waterman Story – Respectable

SAW also recycled material. Mandy Smith’s Got To Be Certain became a hit for Kylie, while O’Chi Brown’s Whenever You Need Somebody was reworked for Rick Astley. A tight, trusty team was coalescing around SAW thanks largely to Waterman’s gift for talent-spotting, and proof of this lay in the meteoric rise of Astley.

Waterman had seen him perform in the group FBI in Warrington and, struck by his soulful voice, brought him to PWL as a tea boy and eventually signed him to RCA. The ‘boy next door’ in the suit from Next had to adjust almost in mid-air to the sudden demands of pop stardom (“that’s not dancing, that’s fear” said Astley of his early performances) when Never Gonna Give You Up became the biggest seller of 1987, a five-week chart-topper.

It was a US No.1 a year later. By Christmas 1987 Astley was being marketed as an old-school crooner covering Nat King Cole’s classic When I Fall In Love.

It was Pet Shop Boys, not Astley, who scooped the coveted festive top spot, but Rick’s remake nevertheless rounded off a triumphant year for SAW. Harding believes this point was their zenith, balancing dance music credibility with pop success.

They had their own hit, Roadblock, a surprisingly gritty piece of dance-funk that joined the likes of the less-successful follow-up Packjammed and deep cuts such as Bananarama’s Mr Sleaze to show yet another side to the team.

Even their flops of 1987 were glorious ones: soul legend Edwin Starr’s Whatever Makes Our Love Grow was a testifying tour de force a la Love Can’t Turn Around, and the Hi-NRG melodrama of Hazell Dean’s Always Doesn’t Mean Forever was a possible blueprint for PSB’s work with Liza Minnelli.

SAW only got bigger in 1988, with Kylie’s mega-success ushering in their ‘pure pop’ phase (see page 102 of this issue for the full tale of SAW and Minogue). Hits came thick and fast for Samantha Fox and Simon Cowell protégé Sinitta (Howells remembers Cowell studying Waterman’s every move, virtually shadowing him), and Hazell Dean got back in the Top 5 with Who’s Leaving Who?

The year ended with a million-seller, the Kylie/Jason duet Especially For You, proof that Waterman, the catalyst with his ‘Woolworth’s ears’, and Stock and Aitken, the alchemists with their melodic gifts, had a unique ability to reflect the desires of a young record-buying public.

In a way, the conversational zing of their song titles recalled the close connection The Beatles had with their pre-psychedelic audience. “This is how people talk – this is how people feel,” says Howells.

Read more: Making Rick Astley’s Whenever You Need Somebody

Read more: Top 40 Kylie tracks

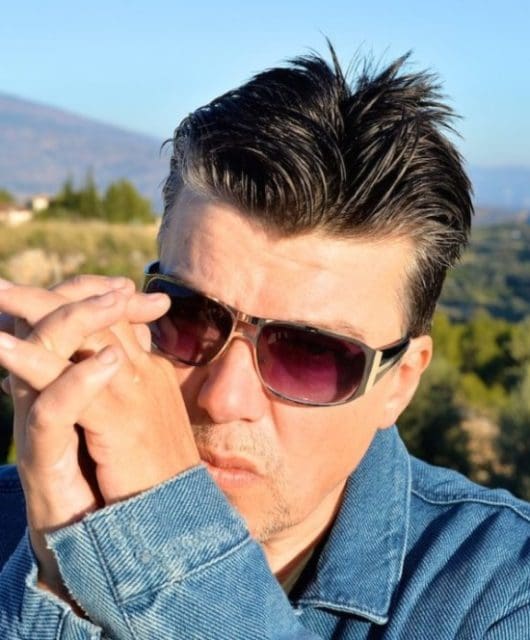

There were, however, some warning signs. The Hitman And Her, Waterman’s late-night trawl through provincial clubland, hit the small screen and hinted at a deepening rift within SAW (“I turned it off after 15 minutes, I was embarrassed,” says Aitken).

The pop/dance balance they’d struck a year ago was becoming complicated. MARRS sampled Roadblock, and they sued (in 1989, guest rapper Neneh Cherry used their 1987 production of Morgan McVey’s Looking Good Diving as raw material for Buffalo Stance).

Harding remembers Rutherford telling a room of DJs at the DMC convention that “We don’t need you any more, we’ve got Kylie”, while SAW themselves got a barrage of abuse from the dance fraternity while receiving an award at the Royal Albert Hall.

This especially hurt Waterman, who was still championing dance culture on TV and praising Stakker Humanoid, but SAW’s sound now had moved towards bubblegum, with harder dance only heard on remixes, Pat and Mick B-sides, or their own SS Paparazzi – another swipe at tabloid culture.

The Stock Aitken Waterman Story – The Hits And The Hate

The industry treated SAW with distrust and envy. Howells remembers the British Phonographic Industry trade association eliminating their ‘Producer’ category as SAW began to dominate pop production. He also recalls how their indie distributor, Pinnacle, incurred the wrath of other indies who decried that PWL “wasn’t really one of them”. The majors, meanwhile, saw SAW as the pop David to their Goliath, beating them at a game they’d had a stranglehold on for decades.

But the hits kept on coming – and so did the Ivor Novellos. Brother Beyond’s SAW No.2 smash that year, the Four Tops-flavoured The Harder I Try, seemed to acknowledge that PWL had truly become the British Motown: Hitsville UK.

The year 1989 would be their commercial peak. The stats speak for themselves: 13 No.1 singles and the biggest-selling album, Jason Donovan’s Ten Good Reasons. New recruits topped the charts (Sonia’s You’ll Never Stop Me From Loving You) and the Top 10 (Big Fun, a flash forward to the boy-band decade that would follow ).

Old-timer Cliff Richard also hit big, with SAW’s assistance. They even revived Donna Summer’s career with This Time I Know It’s For Real and Another Place, Another Time. They were the three Midases of pop. They could get a hit with anyone; even The Reynolds Girls’ I’d Rather Jack. Smash Hits covers were graced with squeaky-clean SAW acts, wholesome and beaming; their records were, to quote Jason Donovan, “happy records for happy people”.

But beneath the pop savvy irreverence of I’d Rather Jack was a rather orthodox structure owing little to the envelope-pushing dance it celebrated (unlike Showing Out).

Read more: Top 40 Stock Aitken Waterman songs

Top 15 SAW albums

“There’s no formula,” claimed Stock. There was however, a need to break down pop to its basic, most communicative form; Stock largely avoided profanity or modish vernacular, anything that might, as he said, “date-stamp” their work. They’d mastered the art of pop – but in doing so, had they, to paraphrase Marc Bolan, broken its spell?

The naysayers thought so. Grumpy TV commentators complained their roster of talent were “human crocheted scarves”. The media dubbed them ‘Schlock, Aimless and Waterdown’. Parodies piled up, from Spitting Image to Morris Minor and the Majors’ parody song This Is The Chorus to French and Saunders, each taking pot shots at the ‘standardised’ SAW sound.

This was not entirely unfair; it was hard to believe the architects of records as slick as Say I’m Your Number One or as lustily feral as You Spin Me Round were now making music with virtually interchangeable synth bass lines and the same synth brass fanfares. Even Matt Aitken had started to think their songs all sounded the same.

If 1989 had been their sun-soaked year, the clouds were gathering. A vintage cover for Kylie, Tears On My Pillow, was SAW’s last chart-topper early in 1990. They struggled to regain dance credibility; occasionally they achieved it, with Kylie’s Better The Devil You Know and Lonnie Gordon’s Happening All Over Again.

“That was the record that was gong to put us back on the map,” says Harding of Gordon’s No.4 smash. Both tunes married current club sounds to sweeping, almost Broadway-ready melodies; SAW at their best. But these gems were in short supply. Major flops returned: Simon Cowell’s Yell, Kakko and Romi Jazz.

Talent, timing and graft had conspired to help them achieve momentous success, dominating the British music industry by 1989. Overnight, everything started to work against them – including each other. Howells attributes their sudden decline precisely to this internal tension; “They stopped talking to one another,” he says. The synergy was gone.

Resentments smouldered. Waterman had taken the spotlight that Stock and Aitken shunned, but the public face of the trio, a myth-maker whom Malcolm McLaren ranked alongside the impresarios of 1950s pop, also took all the credit.

It was hard hearing how he’d written a song with Jason on the loo in three minutes when it was your work, and it had taken considerably longer.

By 1991, Aitken had left. It wasn’t just inter-team wrangles; they’d shoehorned themselves into a niche that was precarious even by pop’s fickle standards.

Not only were last year’s Kylie/Jason fans the next year’s Roses/Mondays record buyers, but the artists themselves tired quickly of their pre-teen following and squeaky-clean image. Kylie ditched Jason and revved up the raunch a la Madonna (she left PWL in 1992).

Donovan struggled to evolve, temporarily emulating Kylie’s new beau Hutchence in the otherwise Beatles-esque I’m Doing Fine video. He never repeated 1989’s success. What was once a winning formula failed to work in a chart full of grittier, harder sounds, from Snap to Nirvana. The dismal No.77 placing of The Twins’ Kylie-soundalike single, All Mixed Up, proved just that.

Soon, Rick Astley asked to be released from his contract. Unlike Motown, one decade’s pop stars would not evolve into another’s album auteurs in the manner of Marvin Gaye or Stevie Wonder. Mel & Kim were brought to a tragic, premature end by Mel’s passing in 1990.

Mike Stock hung on for another couple of years, but successes were few. Then Waterman, in Stock’s words, “sold the family silver”, flogging half of PWL off to Warner Music, squandering their hard-won independence. His songs went largely unrecorded, while cheaply imported PWL acts prospered. By 1993, he was gone.

What was snootily dismissed as “cheesy rubbish” by many observers at the time has aged surprisingly well, especially when one considers their entire output, their hits and misses. Stock and Aitken’s cohesive songwriting has proven, with age, to be the work of real craftsmen (a SAW musical is imminent).

It’s also doubtful whether the music business will see quite the chutzpah and the vision of Pete Waterman again. As Howells says, Stock Aitken Waterman represented everything that was great about pop: fun, youth and innocence.

Check out SAW’s website