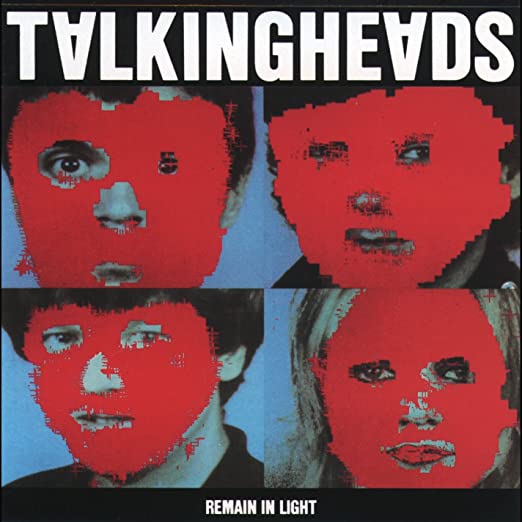

Making Talking Heads: Remain In Light

By Classic Pop | August 11, 2021

Talking Heads’ Remain In Light remains the art-rock quartet’s signature album. By Gary Tipp

During the early part of their career Talking Heads were inextricably linked to the Ramones. Admittedly, both bands had broken out of New York’s legendarily grubby Bowery scene at the same time and, in Sire, they shared a relatively hip record label.

Nonetheless, it was always an odd coupling. Talking Heads’ first ever gig at CBGB’s was second on the bill to the seminal punks from Queens, and in the late spring of 1977 the two bands even embarked on a European tour together.

Schlepping around Europe on the same tour bus only served to amplify the chalk-and-cheese nature of the relationship. On one occasion, a stop suggested by Heads’ drummer Chris Frantz to check out Stonehenge, en route to a gig at Penzance Winter Gardens, caused ructions within the ranks of the Ramones, specifically Johnny, who refused to get off the bus.

“I don’t want to stop here. It’s just a bunch of old rocks,” exclaimed the reactionary rocker.

Musically, as well as culturally, they were polar opposites. The leather-clad Ramones permanently harked back to the golden age of rock‘n’roll, while the smart leisurewear-clad Talking Heads were future-minded and constantly evolving.

The one thing the two bands did have in common, though, was a heavy slice of interpersonal dysfunction. The members of both bands really didn’t get on with each other. Johnny and Joey, notoriously, didn’t speak to each other for most of the Ramones’ 22-year history.

Within Talking Heads the husband and wife rhythm axis of drummer Frantz and bass player Tina Weymouth were often at loggerheads with frontman David Byrne.

Much of the friction was borne out of the fact that when the band signed their recording contract, Byrne had indelicately requested that Weymouth audition for her place in the band again.

Both Frantz and Weymouth were worn down by the singer’s passive-aggressive machinations and, what they perceived to be, a lack of any acknowledgement for their creative endeavour within the band.

Tensions were heightened through Byrne’s seemingly conspiratorial relationship with producer Brian Eno, who had sat behind the controls and fiddled knobs on 1978’s More Songs About Buildings And Food and Fear Of Music a year later.

What’s more, art-rock’s two nutty professors cemented their close bond on the ambitious collaboration My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts. “They’re like two 14-year-old boys making an impression on each other,” swiped the scoffing bass player.

Recording Talking Heads: Remain In Light

It was into this antagonistic atmosphere, albeit in the pleasantly sunny surrounds of Nassau’s Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas, that the initial sessions for the band’s fourth album, Remain In Light, were cast.

The sonic template for what would turn out to be their most enduring masterpiece was actually laid down on the opener of their previous album, Fear Of Music’s polyrhythmic I Zimbra.

The track was a compellingly propulsive combination of Africa-influenced drum sounds melded with a funky disco bassline and Byrne chanting nonsensical Dadaist poetry over the top.

In many ways I Zimbra was an unlikely touchstone, as on the surface of things the band weren’t exactly the closest of cousins to Fela Kuti, the afrobeat pioneer, whose 1973 Afrodisiac album was a major influence on the track. But the band and producer, Eno again, were committed to exploring its possibilities into a whole album’s worth of material.

With AC/DC entrenched in Compass Point’s Studio A recording comeback album Back In Black, Talking Heads established camp in Studio B.

With no songs formally written, it was agreed that the studio be utilised as a tool for composition with the music created by the band members out of improvisation – with producer/collaborator Eno to be regarded as the group’s fifth member.

Talking Heads: Remain In Light – Houses In Motion video

As Frantz recounts in his autobiography Remain In Love, “We were interested in creating sounds that would take us deeper and far beyond what people had come to expect from us.”

To achieve this ambition rather than start with a traditional song structure or lyric, the band would create multiple fragments of songs through improvised jam sessions.

Frantz recalls: “My personal challenge and Tina’s was to conceive and perform rhythm parts that not only grooved like crazy and propelled the song forward, but that also sounded shockingly new… Tina and I created parts that were loops performed live. Then David and Jerry [Harrison] could superimpose their parts over ours.”

Byrne explained his take on the process as best he could to the Library Of Congress in 2017: “We were listening to African pop music, like Fela Kuti and King Sunny Adé, but we didn’t set out to imitate those. We deconstructed everything and then as the music evolved, we began to realise we were in effect reinventing the wheel.

“Our process led us to something with some affinity to afro-funk, but we got there the long way round, and, of course, our version sounded slightly off. We didn’t get it quite right, but in missing, we ended up with something new.”

With the Compass Point sessions over and the basic tracks laid down, the band returned to New York for more recording in the Sigma Sound studios. It was here that simmering tensions started to boil over with Frantz and Weymouth feeling unwelcome.

This is how Frantz recalls the experience in Remain In Love: “It seemed as if [Byrne and Eno] thought of us as sidemen who were no longer useful to them. At one point Brian actually said to us in his most bothered tone of voice, ‘There are too many people in the control room.’” It was a comment that the rhythm section clearly didn’t take too kindly to.

Talking Heads: Remain In Light – Crosseyed And Painless video

Niceties aside, the work that Byrne, Eno and Harrison were putting in was getting results. Former King Crimson guitarist and Bowie acolyte Adrian Belew was shipped in to add wild, crazy solos to several tracks, while avant-garde trumpet player Jon Hassell contributed freaky brass. Nona Hendryx, formerly one third of girl group Labelle, was also invited to add backing vocals.

Read our Lowdown feature on Talking Heads

Read more: Making Blondie’s Parallel Lines

It was around this time that art school alumni Frantz and Weymouth began to work on concepts for the album cover. The couple had met at the Rhode Island School Of Design in 1973, and it was there that Frantz first formed a band, The Artistics, with fellow student David Byrne; who was often referred to back then as ‘Mad Dave’ among the drummer’s circle of friends (if ever there was a warning sign…).

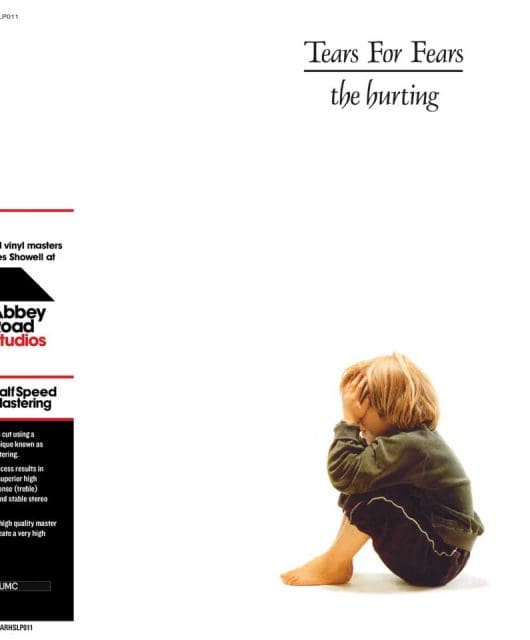

Remain In Light’s artwork was created digitally, which was then a new-fangled, cutting-edge process, with the aid of the Massachusetts Institute Of Technology’s powerful mainframe computer.

Initially, the iconic photograph of the US fighter planes was planned for the front cover (Tina’s father had flown Grumman Avengers during his Navy service) with the band portraits destined for the back.

However, the roughly painted bright red masks crudely splodged over the headshots made for an impactful image and the roles were reversed.

With the album finally completed, the perennially thorny issue of songwriting splits and credits was broached. Eno had wanted the album to be called Remain In Light by Talking Heads and Brian Eno, but he was eventually talked down.

After some discussion it was agreed that writers’ credits should read ‘All Songs By David Byrne, Brian Eno, Chris Frantz, Jerry Harrison and Tina Weymouth.’ The names were in alphabetical order, and the final LP artwork was signed off as such.

However, when advance copies of the LP were circulated, the writing credits had been altered to ‘All Songs By David Byrne, Brian Eno, Talking Heads.’

What’s more, the lyric sheet on the inner sleeve had been changed to ‘All Songs by David Byrne and Brian Eno, except The Overload and Houses In Motion written by David Byrne, Brian Eno, and Jerry Harrison’. It was a sleight that must have felt like a huge, hurtful smack in the mouth to Frantz and Weymouth.

Nonetheless, the album was released on 8 October 1980 to widespread critical acclaim, featuring high across-the-board ratings in the music press best of year polls – coming first in both Sounds and Melody Maker, while placing sixth in NME.

While not remotely interested in touring himself, Eno believed Remain In Light to be too dense for a quartet to take on the road, and so the lineup was extended to nine members for live performances.

To beef up the band, Adrian Belew was joined by Funkadelic’s living legend Bernie Worrell, alongside bassist Busta Jones, percussionist Steven Scales and backing vocalist Dolette McDonald. The nucleus of which would remain intact for 1984’s concert film Stop Making Sense and the soundtrack album of the same name.

Following a hugely successful world tour with the big band and after releasing four albums in just as many years, Talking Heads, sensibly for all concerned, went into a three-year hiatus.

Byrne worked on a musical score for US choreographer and dancer Twyla Tharp titled The Catherine Wheel, while Harrison’s first solo outing was called The Red And The Black. Frantz and Weymouth returned to Nassau, where they now owned a property.

Venturing into the same studio where Remain In Light was initially recorded, they formed side project Tom Tom Club and scored a couple of substantial worldwide hits in Wordy Rappinghood and the much-sampled Genius Of Love.

Talking Heads continued to work together for four more studio albums, but the psychic toll in daring to reach the creative heights of Remain In Light meant the damage was beyond repair, and what was once the most searingly sharp of cutting edges was now blunted.

Talking Heads: Remain In Light – The Songs

Born Under Punches

(The Heat Goes On)

If any casual listener was unaware that Talking Heads were heading down previously unexplored sonic avenues with their fourth album then straight out of the gate Remain In Light’s blisteringly polyrhythmic opener would soon enlighten them. Byrne’s born-again preacher persona makes his first appearance (“I’m not a drowning man/ And I’m not a burning building/ Drowning cannot hurt a man/ Fire cannot hurt a man”), sermonising over an unholy, funky racket.

‘The Heat Goes On’ refrain repeated in the chorus was based on a headline Eno read in the New York Post during that summer’s long-lasting heatwave. The greatest trick the band pulled off with Remain In Light is that for an album so heavily steeped in experimentation its melodic pop-sensibility was still to the fore.

In other words, art you can dance to.

Crosseyed And Painless

The ludicrously complex song structures that the band cooked up in the improvised jam sessions at Compass Point resulted in a set of backing tracks unlike anything Talking Heads had written before. The problem with this new approach for principal songwriter David Byrne was that he struggled to adapt his usual word patterns to them and suffered from writer’s block as a consequence.

That was until he adopted a stream-of-consciousness approach to his lyric writing, a method that was heavily inspired by the nascent rap scene breaking out of New York City at the time. The rhythmical rant in Crosseyed And Painless (“Facts are simple and facts are straight/ Facts are lazy and facts are late”) was directly influenced by Kurtis Blow’s early classic The Breaks after a suggestion in the studio made by rap fan Frantz.

The Great Curve

At 6:28, the hypnotic The Great Curve clocks in as the longest of the three tracks on Side One. This being Talking Heads it was never going to be an album full of songs with straightforward unrequited boy-girl love narratives. To this end, The Great Curve is best described as an eco-feminist tribute to the mother of all life, the goddess Gaia

(“The world moves on a woman’s hips/

The world moves and it swivels and bops”). Undeniably, it’s one of Talking Heads’ finest moments on record as a band, the groove-based track is a swirling mass of guitar, bass, percussion and inter-meshing vocal chants. The Great Curve is also notable for the synthesiser-treated guitar solos from a possessed Adrian Belew.

Once In A Lifetime

The first track on Side Two was originally known under its working title of Weird Guitar Riff Song, and to this day the existential Once In A Lifetime remains Talking Heads’ most famous song (it was certified silver in the UK in 2018). The album’s first 45, it made its way up to No.14 in the UK Singles Chart in February 1981.

There are many different interpretations of the track’s meaning, but Byrne himself has always stated that the lyrics aren’t meant to be cryptic or misleading. He said: “We’re largely unconscious. You know, we operate half awake or on autopilot and end up, whatever, with a house and family and job and everything else, and we haven’t really stopped to ask ourselves, ‘How did I get here?’”

Once In A Lifetime’s most prestigious moment occurred when diehard post-punk Kermit The Frog performed it on an episode of Muppets Tonight dressed in a David Byrne over-sized boxy suit.

Houses In Motion

Houses In Motion is the second single from the album and peaked at No.50 in the UK Singles Chart. Featuring a lengthy distorted horn improvisation from the ambient pioneer Jon Hassell together with an oblique spoken narrative intro from Byrne (“For a long time I felt without style and grace/ Wearing shoes with no socks in cold weather/ I knew my heart was in the right place”), it was never going to contend for the top spot.

The relentless afro-groove temporarily slows and a fog of spooky paranoia settles in, this is the Byrne-Eno alliance operating at the peak of its slanted powers. No Kermit The Frog on this one.

Seen And Not Seen

This spoken-word track discovers Byrne ditching the preacher-man character and talking like a regular guy (or his approximation of one, at least). Over a stomp-clap percussive rhythm he calmly narrates the seemingly straightforward story of a man who wants to change his face, either to match his true personality or to represent a personality he’s always wished he had (“He would see faces in movies, on TV, in magazines, and in books/ He thought that some of those faces might be right for him”).

Listening Wind

This simmering lament with its Arabic sound recounts the tale of Mojique, a bomb-planting, anti-American resistance fighter, who thinks back to the days before Americans arrived in his country (“Mojique holds a package in his quivering hands/ Mojique sends the package to the American man”). The atmospheric track was covered by Peter Gabriel on his 2010 covers album Scratch My Back.

The Overload

Swapping the downright funky for the positively funereal, the album’s bleak and curious closing track was Talking Heads’ tribute to Joy Division. Curiously, none of the Heads had ever heard any of the gloomy foursome’s records, but they were so intrigued by ecstatic album reviews the Mancunians were receiving in the music press that they decided to go for it anyway.

Despite this oblique approach, the droning, bass-heavy dirge of Remain In Light’s least danceable song is not without the familiar essence of Ian Curtis and his sombre chums. After the groovy afro-funk of what’s come before, The Overload comes as a blessed relief only to the dancefloor-shy miserabilists among us.

Visit David Byrne’s official website

Read more: Top 20 Side Projects