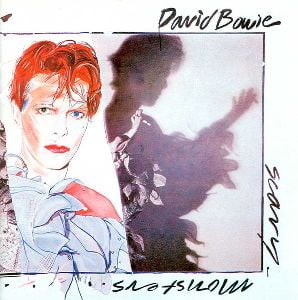

Making David Bowie: Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)

By Matthew Lindsay | September 7, 2021

While the New Romantics were still largely a secret to the outside world, their hero was dreaming up a soaring rock record, a multi-layered, dystopian masterpiece – Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)…

The 70s were over. David Bowie had swung through the decade like Tarzan; beginning it as a glam rock superstar, conquering America with ‘plastic soul’, developing a near-lethal cocaine habit, recuperating in Berlin, making a trilogy of ground-breaking albums with Brian Eno, returning to painting.

In 1979, he divorced Angie, and that year’s Lodger was to be his last with Eno until 1995’s Outside. As the 80s began, his fingerprints were everywhere, from artists as disparate as Joy Division, Kate Bush and Gary Numan to the burgeoning New Romantic movement.

Even a gruesome scene in William Friedkin’s film Cruising had emulated Lodger’s cover. Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), its title inspired by a Kellogg’s cornflakes packet, would see Bowie re-examine and recycle his own past, a past everyone else was drawing from.

Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) was an album of contradictions, raw emotions and glossy surfaces, grinding noise and slick production; glancing backwards, yet propelling Bowie into the 80s. It had the air of a cumulative work – supremely confident, but plagued with self-doubt. In 1990 Bowie described the record as a kind of ‘purge’; it’s haunted by the ghosts of past creations, spooked by its creator’s personal demons and those of the wider world.

Basic tracks were recorded at NYC’s Power Station in the early months of 1980. During these sessions Bowie only had one song completed, It’s No Game, which would bookend the album in radically different incarnations.

During the sessions, rhythm guitarist Carlos Alomar, bassist George Murray and drummer Dennis Davis recorded grooves from which Bowie would later sculpt songs.

Other visitors to the sessions included the E Street Band’s Roy Bittan, whose ivory-pounding provided the album with the ‘grit’ Alomar says the band were seeking, while Chuck Hammer’s guitar synth, a Roland GR-500, gave the album layers of cutting-edge polish referred to as ‘guitar-architecture’.

Co-producer Visconti claimed the proviso for Scary Monsters was that it was to be a Sgt. Pepper’s, a state-of-the-art masterpiece with each track given its own sonic identity.

Recording then moved to London’s Good Earth studios for vocals and overdubbing. This was the first Bowie album to be partly made in the city since 1974’s Diamond Dogs. Situated in the heart of Soho, the area was full of memories for Bowie, from Lindsey Kemp’s Bateman Street apartment to the Marquee Club, where he had held gigs he called ‘Bowie Showboats’ in the mid-60s.

In his time with Eno, Bowie had taken to devising lyrics spontaneously; on Scary Monsters he spent two months on the compositions. Crucial appearances at the Good Earth sessions came from guitarist Robert Fripp and synth player Andy Clark from Be-Bop Deluxe (on Minimoog and Yamaha CS-80). Even The Who’s Pete Townshend showed up, in a “foul laconic mood” according to Visconti, to add guitar to Because You’re Young.

In August 1980, Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)’s first single, Ashes To Ashes, hit the shelves. Bowie had been thinking about a sequel to Space Oddity ever since he revived the song in a sparse new arrangement for Kenny Everett’s 1979 New Year’s show.

Ashes To Ashes exposed Major Tom as a junkie, drifting, Bowie explained, in a “cosmic space that was feeding him like some heroin-y type addiction, desperate to return to the Earth, to the womb”. It mythologised his famous creation, and shattered the illusion. The parallel between Bowie’s struggles and his characters were impossible to ignore.

NME’s Angus Mackinnon found Bowie in a mood of lacerating self-analysis, full of doubt about his legacy (mirrored by the Ashes lyric “I’ve never done good things”). It was a typical Bowie irony that he would be saying this as he released one of his finest records.

From its heavily flanged piano and layers of choral guitar synths to Clark’s Minimoog outro, Ashes To Ashes compressed an album’s worth of ideas into one song. Bowie’s vocal changes from line to line; first comic-book heroic, then jubilant, gossipy, resigned and impassioned.

His vocal is joined by others: in the second bridge he’s echoed by ghoulish mutterings, while the melody is as searing as the one found on Life On Mars? The singer himself compared the chorus with the nursery rhymes of the late 19th century, “horrid little rhymes about getting your ear cut off”.

Ashes To Ashes wasn’t alone in this; 1980 seemed to be full of dark nursery rhymes (earlier that year there’d been Peter Gabriel’s Games Without Frontiers; later there would be Kate Bush’s Army Dreamers, and you could even add The Cure’s A Forest and Siouxsie’s Happy House to the list of sinister whimsy).

The single came with a striking sleeve with Bowie dressed in full pierrot garb and a ground-breaking video. Just like the song, the outfit harked back to Bowie’s past with Lindsay Kemp (it was designed by Kemp-era costumier Natasha Korniloff), but it also embraced a ‘now’ that was indebted to Bowie (Covent Garden’s Blitz was just a quick limo ride from Soho’s Good Earth).

In Ashes To Ashes, Bowie was assimilating the movement that he’d inspired before most of them had even hit the charts; Spandau’s debut was still several months away.

In September 1980, Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) was released, following Ashes To Ashes all the way to the top. The sleeve art was taken from an 8 by 4 foot painting by Vogue/Tatler illustrator Edward Bell. He was given just a week for the commission; the painter came to photographer Brian Duffy’s studio, where Bowie was in the full pierrot look, heavily made up by Richard Sharah, all topped off with pointy hat. Bell asked Bowie to remove the hat and smudge the make-up and play with the costume.

The finished sleeve placed Bowie at the heart of the New Romantic zeitgeist, but the decadent glamour of Bell’s portrait was darkened by a shadow Bowie, cigarette in hand, from the Duffy photograph, occupying half the cover’s space. It was like a looming image from the German Expressionist movies Bowie loved, peopled with doppelgangers and fractured personalities… perfect for an album whose first English line was “silhouettes and shadows”, striking a stylish pose while being full of decay.

Inside the sleeve was a complex, multi-layered beast of an album. Bookended by the sound of Visconti’s Lyrec 24-track tape machine rewinding at the start then spooling out at the end, Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) allowed Bowie’s fraught, theatrical imagination to run riot in a way it hadn’t since Diamond Dogs. He rummaged through his own basement, not just digging out Major Tom.

It’s No Game incorporated passages of Tired Of My Life – a slice of folky introspection written when he was 16 – and Fashion lifted the “beep-beep” from his kooky obscurity Rupert The Riley. He borrowed the line “people from bad homes’” from a song title by The Astronettes, an abandoned project for his then-girlfriend Ava Cherry.

Another Astronettes track, I Am A Laser, was reworked as Scream Like A Baby, now with a varispeed section, an oft-used Bowie technique since The Laughing Gnome. If everyone else was referencing Bowie, then why shouldn’t he?

But Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) was rife with modern horrors. Bowie’s dystopian dread is in overdrive on It’s No Game and Scream Like A Baby, both warning of a hideous future on the way (he spoke of the awful 80s before the decade had even really started).

Both recall the terror of Diamond Dogs’ second side, both sound like George Orwell’s 1984 future – ‘the sound of a boot stamping on a face forever’; mechanical, grinding, art-rock. It’s No Game (Part 1) is a cacophony of invention, taking in the gated drums that would define the decade and larynx-shredding catharsis influenced by Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

The title track is equally harrowing: a psychodrama about “a criminal with a conscience, who corrupts a young mind”, the song’s victim recalls the blankly-staring housewife in Repetition. Dogs bark, things go bump in the mix – cowbells through effects pedals, bass through a Kepex noisegate – while Fripp’s atonal riffing skitters through the murk like a madman on the run.

Fripp’s skronky guitar work on Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) has almost as ‘vocal’ a presence as the singer, and gives the album much of its character. Bowie was keen to stress to Angus Mackinnon in the NME that the music itself carried as much of a message as the lyric sheet, often contradicting it. Fripp is the central antagonist here, constantly gnawing at, tearing at the fabric of the glossily-constructed record.

On Fashion, his dissonance disrupts the disco like an intruder (these parts were curbed, unsurprisingly, for the single edit). Fashion was intended by Bowie to be an update of The Kinks’ Dedicated Follower Of Fashion, an ode to how wearying staying hip can be. Bowie recalled how the “high-powered enthusiasm” of the early disco scene in the 70s had been replaced by “grim determination”.

It sounded like he was casting a withering glance at his own children, the Blitz Kids. On an album bristling with humanist indignation, Fashion seemed full of messages, with images of goon squads reducing the political spectrum to moves on the dancefloor.

If Fashion was taking pot shots at the Blitz-goers and their ilk, so was Teenage Wildlife. For years, Gary Numan thought it was about him (Bowie had allegedly had him removed from the Kenny Everett show). One line – “as ugly as a teenage millionaire/ Pretending it’s a whizz kid world” – even resembled the New Romantic critics’ assertion that they were just ‘sipping champagne on daddy’s credit card’.

Bowie himself claimed the song was about taking a short view of life, warning his descendants of the battles ahead, of how quickly the latest pop star in “brand new drag” will be discarded.

As always with Bowie, the song defied any easy reading, zigzagging between contempt, compassion and parental concern. He even suggested the song was a note to ‘a younger self’, hungry for fame, with “squeaky clean eyes”, unaware of how hard it would be and the toll that it would take. Seeing how quickly his cultural offspring were making an impression, it was perhaps inevitable that Bowie felt a tad resentful of the lack of dues paid.

Funnily enough, Gary Numan, interviewed in Smash Hits in 1981 with his star already descending, sounded just as world-weary and fatalistic as the lyrics to Teenage Wildlife, claiming his fans would replace him swiftly if he died (presumably with Adam Ant).

Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) was a critical success. Plans for a tour were nixed, however, when his friend and mentor John Lennon – a regular visitor to the NYC sessions – was assassinated in December 1980. Distraught, Bowie fled to Switzerland.

Two more singles were lifted from the album after Fashion (the title track and Up The Hill Backwards), without videos. Bowie had ended the 70s in a way similar to how his life would end, with a dark, soul-searching masterpiece (2016’s Blackstar), working in theatre (Lazarus) and a concerned parent, troubled by violence in the world.

But Scary Monsters wasn’t the end. He would return with one last arty excursion, Brecht’s Baal; a No. 1 with Queen, Under Pressure, and a Moroder collaboration (the Cat People’s theme song) before returning in 1983 with a healthy tan and mega-success. For all Scary Monsters’ ‘purge’ and shedding of former skins, Let’s Dance would be his biggest role yet.

Read more: The Story Of The New Romantics

Read more: Making Visage

Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) – The Songs

It’s No Game Pt.1

Scary Monsters opens with a loose, louche swagger, a stylised protest song topped by Fripp’s skirling, dissonant guitar and featuring a rhythmic wallop with Davis’ drums routed through Visconti’s Eventide Harmonizer (the resulting heavy crunch echoes the first side of Low and brings to mind Phil Collins’ gated drums on Intruder from Peter Gabriel’s III, released earlier that year – another state-of-the-art 80s production). Michi Hirota, Sparks’ Kimono My House cover star, spews out a translation of the main lyric, more samurai than geisha, while Bowie stretches his words to the point of inarticulate rage, inviting obvious John/Yoko comparisons. All this avant-garde cacophony is not without its humour – there’s an absurdity here that predicts being spoofed by the Hee Bee Gee Bees on I’m Quite Ahead Of My Time – but in the same year as Lennon’s shooting, the line “put a bullet in my brain” is a grim prophesy.

Up The Hill Backwards

The three-way vocal – Bowie, Visconti and Lynn Maitland – is like a Greek chorus warning of how eternity mocks all human endeavour, of how ignorance is bliss (a joke at the expense of the 1967 self-help manual I’m Ok, You’re Ok), and shuffled within its lines may well be some autobiographical material. The deliberately MOR trappings of the wistful vocal melody are juxtaposed by the wild Bo Diddley-style freakout of the instrumental passages. Release control, the singers say; seize the moment, says Fripp, whipping the song into a concluding frenzy. It’s a masterpiece of tension and release. The video-less single, the last to be lifted from the album, found its way on to TOTP accompanied by Legs & Co.

Scary Monsters

“A bit of Londonism” said Bowie of the title track at the time, putting the song there via his exaggerated Mockney delivery. Visconti tinkered endlessly with the tracks, adding effects and splicing them back into the tape, the kind of painstaking analogue invention that made those Sgt. Pepper’s comparisons make sense. The third single from the album, the title track is oft-compared with Joy Division’s She’s Lost Control (The Psychedelic Furs come to mind, too).

Ashes To Ashes

Originally an instrumental entitled People Are Turning To Gold, Ashes to Ashes was the first single from Scary Monsters. Ominous but infectious, its glacial soundscape made funky by George Murray’s slap bass and Davis’ “octopus-like” mastery of drums and hi-hat, Ashes to Ashes gave Bowie his first No. 1 since its predecessor Space Oddity in 1975, knocking Abba’s The Winner Takes It All off the top spot.

Fashion

Originally entitled Jamaica. Andy Clark’s sequencer opens the track like a warped groove; a tight metronomic beat recalls the robotic strut of Pop Muzik, and Fripp’s fretwork is the great disrupter. Bowie was ready to abandon the song until Visconti urged him to complete a lyric, aware of hit potential (the result is a cousin, of sorts, to Fame and Golden Years). The producer was right; when released in October 1980 Fashion was another UK hit, making No. 5 in the charts.

Teenage Wildlife

Whether it was written as Bowie’s warning to all the little Ziggys following him into the charts or yet more ‘lacerating self-analysis’, Teenage Wildlife was as dense as it was winding (it’s the album’s longest track, clocking in at nearly seven minutes). Fripp cribs his own soaring Heroes guitar riff, twisting it into lines reminiscent of New York’s Television. Bowie’s vocal shifts shape too, switching between hoarse agony (“a wolf in a trap”), exaggerated crooning and even baby cries. The result was a personal Bowie favourite: “I’ll give you two Modern Loves for it,” he once said. Listen closely for bells buried in the mix.

Scream Like A Baby

A thudding, mechanical horror, almost industrial in its might. Power gone mad, controlling and destroying its hapless inhabitants, is favourite Bowie terrain; see Saviour Machine. For all Bowie’s histrionics here and elsewhere, the song foreshadows much of what would come to pass in “those dreadful 80s” he spoke of. The racially-charged riots of 1981 were just a year away from “they came down hard on the street”, while homophobic backlash would become all too real with the advent of AIDS. This futuristic dread is alleviated by a sweeping chorus that, like Ashes To Ashes, crashes to earth at the last line, and a playful varispeed section. A line about “old songs we loved” reminds us that nostalgia was always the ghost in the machine of this most forward-thinking artist.

Kingdom Come

Bowie often covered writers who he felt deserved a bigger audience; this composition first appeared on Tom Verlaine’s solo debut. With Television, Verlaine had made the seminal Marquee Moon (1977), the kind of arty, nervous New Wave that Bowie seems to have tapped into on Scary Monsters (there are shades of Talking Heads, too). Kingdom Come was a cosy fit on this unsettling album; even the image ‘breaking rocks’ featured in Bowie’s own compositions, and the paranoid image of someone watching in a tower evoked memories of Heroes and Hansa by the Berlin Wall. Verlaine apparently turned up to play on the song armed with 30 rental amps, but Fripp played on the finished recording instead, while Bowie’s fabulously overwrought vocal is a nod to Ronnie Spector.

Because You’re Young

This, in his own words, is Bowie playing the “old roué… gazing down on young lovers”, painfully aware it will never last. The mood is more tender than on Teenage Wildlife, though still desperate. Pete Townshend’s fretwork is savage and slick, more 80s sessionman than Who powerchord merchant (the nearest he gets to the 60s is a Beatles-esque gearshift in the last few seconds). Perhaps the LP’s most underrated song, Because You’re Young flashes forward to the big romantic melodramas of the later 80s (Loving The Alien, Absolute Beginners, When The Wind Blows).

It’s No Game Pt.2

Actually the first version of the song to be recorded. Fripp, and angst, are nowhere to be found. Bowie described this incarnation as “gentle, lilting, nostalgic”. Taken together, the two versions represent two halves of Bowie’s whole; the drama queen and the ice man. With just Alomar, Murray and Davis providing the backing, it brings an anguished, soul-searching album to a close with a slow dance. Pt. 2 replaced the original final track, the instrumental Fuje Moto San, which acted as proof that Bowie could do ambient, electronic sounds without Eno. Used as Japanese Saki ad music, it eventually surfaced as Up The Hill Backwards’ flipside, retitled Crystal Japan.

Check out David Bowie’s website here