Visage album cover

The New Romantics brought a burst of colour and style to a drab and depressing music scene in the first years of the 1980s…

‘Fame Fame Fame – what’s your name?’ said the flier. It was a Bowie quote for a Bowie club night, held weekly at Billy’s. Situated in the heart of Soho underneath a brothel with Rusty Egan as its house DJ, the club attracted a small but fiercely dedicated crowd, heavily made up, outrageously attired, all eager to see and be seen.

Among the outcasts and the peacocks were George O’Dowd and his friend Peter Robinson (both to be transformed into Boy George and Marilyn), Siobhan Fahey (Bananarama) and a whole host of aspiring artists and designers. The night was so popular Egan brought in his flatmate, Steve Strange, as gate-keeper.

A few months later, they’d moved on to Tuesday nights at the Blitz wine bar in Covent Garden. Strange still kept guard, more a Pied Piper than your average doorman. Inside Blitz, with its war-time décor (gingham tablecloths, dusty lamp shades, Churchill posters), Bowie (and Roxy) remained at the centre of Egan’s ‘electro-diskow’, joined by the likes of Kraftwerk and Giorgio Moroder soundtracks.

Yellow Magic Orchestra and The Human League featured as well as oddities he’d acquired in Berlin (Gina X’s No GDM, Telex). “It didn’t have to be danceable, it had to be right,” said Egan. Bowie’s Warszawa would be followed by Grace Jones’ La Vie En Rose with maybe a burst of Flash Gordon in between.

The crowd was equally diverse. The faithful from Billy’s flocked there (O’Dowd would soon be the cloakroom attendant), planning their outfit for a whole week; boys and girls of all sexual persuasions, including a bunch of working-class lads from the Angel’s council estates who would soon form the club’s house band, Spandau Ballet. Squat-dwelling, dole-claiming ‘fantastic nobodies’ would rub shoulders with somebodies like film-maker Derek Jarman or former punks Siouxsie Sioux or Billy Idol.

Strange’s door policy was strict. The look, not VIP status, guaranteed you entry. Infinite sartorial variety was on display. The Blitz was like a series of tableaux from a Fellini movie. DIY glamour; repurposed clobber from charity shops, costume (togas, O’Dowd’s Boadicea) and fancy threads purchased from the PX boutique nearby (Strange worked there).

Read more: Top 40 Duran Duran Songs

Read more: Making Visage

Artist Mark Wardel (aka TradeMark), a Blitz regular, recalls seeing a PX favourite there, a space-age suit, as worn by Numan; it made him look like “an extra from Star Wars”. Futurist garb vied for attention with those raiding the wardrobe of history: 40s Hollywood glamour, Fauntleroy collars, Robin Hood outfits.

Crucially, a sale at Berman’s and Nathan’s costumiers meant Blitz-goers scooped up all manner of one-off period pieces, transforming the dandies into Regency Libertines or Elizabethans.

Ransacking history or flashing forward into the future both meant escape from the gloomy present. Punk had confronted the moment (“Now is the time to realise, to have real eyes”, howled Lydon in I Wanna Be Me), but this new scene sought refuge from drab late 70s England with its rising unemployment and rising uncollected garbage.

The New Romantics: Designs for life

The Blitz was a powerful magnet for creativity. Redefining the club-goer as a star in their own right demanded it from the crowd. It also turned the crowd into one giant muse for artists. Mark Wardel: “When I first saw George [O’Dowd] he had birds in his hair, eyebrows halfway up the forehead, a kimono on. He was a perfect subject for a painter.” So too was Strange; Wardel painted both.

Designers were a constant presence (it was referred to as ‘St. Martin’s Common Room’); from Julie Sissons and Judith Franklyn to Stephens Jones and Linard and Chris Sullivan. Throw in film-makers (John Maybury) and writers such as Robert Elms (who found Spandau’s name scrawled on a Berlin wall) and Perry Haines, and you had an intense hub of young creative energy.

Haines summed up the Blitz’s defiant decadence: “little Neros fiddling while Rome burns”. But he argued they weren’t escaping reality… merely creating an alternative one.

New scenes need new sounds. Strange and Egan formed Visage with Midge Ure, Egan’s bandmate from the Rich Kids, and an ever-revolving cast of characters from established bands – Billy Currie (Ultravox), Chris Payne (Gary Numan) Dave Formula and John McGeoch (Magazine). By September ’79 they’d issued a debut single, Tar.

Read more: Making Spandau Ballet’s Journeys To Glory

If Visage were a musical project fronted by a popstar as mannequin, Spandau Ballet were a real gang. Their influences were as eclectic as the Blitz crowd, the jagged edges of punk smoothed down by soaring synths, four-on-the-floor disco rhythms and a singer, Tony Hadley, who in Strange’s words, “sounded like Frank Sinatra” (his parents loved the crooners).

Soul boys (they’d previously been The Makers and The Gentry) with Gary Kemp, a Bowie fanatic as songwriter, Spandau, along with Visage, were making European Dance Music. Spandau Ballet’s journey to stardom took a uniquely anti-rockist route: early shows were club events, taking place at unusual locations; the HMS Belfast, Birmingham Botanical Gardens, London’s Scala cinema.

They circumvented the inky weeklies altogether in their rise to fame. The NME still clung to the political dogma of much of punk – but this was entertainment.

The New Romantics: Feel the gaze

Nevertheless, punk had attuned the media to emerging youth subcultures. The Blitz Kids “make the punks look normal” reported the Daily Mirror in March 1980. TV coverage followed. LWT’s 20th Century Box captured an early Spandau (Tony Hadley: “it’s a question of elegance and romance”). A news report interviewed a pre-fame Marc Almond, who explained the new credo: “It’s all about dressing up and having fun and being individual”.

His presence indicated that whatever ‘it’ was, it wasn’t just relegated to the Blitz or London. The New Romantics, as they were newly-named, were all across the nation. Other names were touted: Futurists, Peacock Punks, the New Dandies… but New Romantic was the one, coined by a journo [by all accounts Betty Page in her 1980 Sounds interview with Spandau Ballet – Ed], which stuck, much to the chagrin of the originators.

It wasn’t just the media that was focussing attention on the scene. Record sales were slumping. A&R men were in hot pursuit of The Next Big Thing after punk, especially those at EMI, eager to fill the void left by the Pistols. They signed Duran by the end of 1980.

Read more: Steve Strange obituary

Read more: Steve Barron interview

By then, Spandau Ballet had already secured an enviable contract with Chrysalis (and an imprint, Reformation). Visage, initially on New Wave label Radar, moved to Polydor. They were perfect fodder for the new colour-heavy magazines challenging those weeklies’ hegemony (see New Sounds, New Styles).

Mick Jagger had been famously refused entry to the Blitz; Strange let others in, including Michael Jackson. Egan claims Island’s supremo Chris Blackwell made one night’s repertoire the content of Grace Jones’ Warm Leatherette LP.

But it was Bowie’s visit that drove the scene overground. He recruited Strange and others to feature in his Ashes To Ashes video, and after that Spandau hit No. 5 with To Cut A Long Story Short (produced by Richard Burgess, whose band Landscape provided floor-fillers for New Romantics like European Man and Einstein A Go-Go).

Visage’s debut album followed the same month, November 1980, housed in a sleeve painted by Iain Gillies from a shot by Peter Ashworth, depicting Strange and dancing partner Vivienne Lynn as stars in their own silent movie.

By the next year, Fade to Grey – part electro-futurism, part Low Euro-blankness – hit the Top 10, accompanied by a promo that made full use of Strange’s (and Blitz Kid Princess Julia’s) striking image. The New Romantics had arrived.

Also breaking through in 1980 was Adam and the Ants with Antmusic and the Kings Of The Wild Frontier album, released the same day as Spandau’s debut 45. Ant didn’t embrace futurism; his music was chanty and tribal, glitter-beat redux with Burundi-style twin drumming. But he raided history’s dressing-up box, creating a Dick Turpin meets Geronimo look. Like the Blitz Kids, he hated the term – but in the popular imagination, Ant was a New Romantic.

The early months of ’81 set the stage for what was to be the Year Of The New Romantic. There was more press in January (a Time Out cover) and the Blitz team put on a live event, The People’s Palace, at Finsbury Park’s Rainbow Theatre (the ‘New Romantic Woodstock’).

Playing there was the revamped Ultravox, fronted by Midge Ure. Released in the first weeks of ’81, Vienna was an even bigger hit than Fade To Grey, just missing the top spot. It boasted a Russell Mulcahy video that was Euro-centric, depicting lavish, bygone party scenes in the face of film noir-style gloom.

Read more: Making Duran Duran’s Rio

This heroic grandeur-amid-decay, set to the song’s futuristic soundtrack, was the essence of the New Romantic distilled. By February, Spandau’s debut album Journeys To Glory had hit the shelves. So too had Duran Duran’s Planet Earth.

Duran had evolved from the same crucible of music, clubbing and fashion as their London counterparts. Like Spandau, they’d been a ‘house band’; the Berrow brothers’ club The Rum Runner was heavily mirrored for posers, boasted a Studio 54-inspired sound system, and had put on obligatory Bowie nights as well as jazz-funk evenings (keyboardist Nick Rhodes DJ’d there).

Duran also shared Spandau’s attention to visual detail. Malcolm Garrett-designed sleeves presented the band-as-brand; boxed imagery on white backgrounds, typeface more akin to a luxury airline than a pop group. They struck an equally stylish pose when they hit TOTP performing Planet Earth (which itself had undergone a timely makeover, courtesy of producer Michael Hurll).

Drenched in dry ice and draped in ruffles and frills (Birmingham’s Kahn and Bell dressed them) here were the Beau Brummels from Birmingham, not the Blitz. Planet Earth even dropped ‘New Romantic’ into the lyric.

Spandau and Duran also shared an ability to balance a startlingly similar array of influences into their own sound (glam, disco, Euro-electronic, a scintilla of punk). Both their debut singles came alive in their extended versions, stretched to maximise danceability.

Play the 12-inch versions of To Cut A Long Story Short and Planet Earth side by side; they are locked in a dance-off/duel, one trying to out-dazzle the other. Both bands’ club roots were bringing remix and nightlife culture into mainstream pop, altering it forever.

The rivalry was real. For their first Smash Hits feature, Duran claimed “Spandau were very often eclipsed by their audience”. And Visage? – They “didn’t really exist”. Fiercely creative, fiercely competitive, the scene had always engendered a degree of one-upmanship.

Much of this was productive. O’Dowd, while living in Birmingham in the late 70s, recalls how friend Martin Degville inspired him to apply make-up more dramatically. But the determined pursuit of individual looks meant feuds could easily occur if someone suspected another of stealing theirs. Now the New Romantic battleground was the charts.

The New Romantics: A crowded dancefloor

Throughout ’81, British pop boomed. Stylishly-packaged, synth-heavy pop dominated – pop that could be easily classified as New Romantic. The Human League, remodelled with two girls plucked from among the clubgoers at Sheffield’s Crazy Daisy, started having hits. The Sound Of The Crowd celebrated life at night, going out and looking good. Dare’s opener The Things That Dreams Are Made Of did likewise.

The sleeve, inspired by Vogue, embodied the spirit of the age: DIY glamour, androgyny. By Christmas, Don’t You Want Me? topped the charts with a Vienna-inspired promo.

Cine-literacy was layered, the song’s original inspiration was A Star Is Born, the video cheekily referenced Euro-cinema (Truffaut’s Day For Night). Oakey, like Ant, hated the tag, but compare the League’s electro sound and recherché vision with Visage’s Visage video.

Read more: Top 40 Depeche Mode Songs

Strange goes from club-land to photo-shoot to screening room, glossy magazines thrown in for good measure. They occupy the same world, an endless aesthetic paradise, living the night life, yearning for the high life. Pure New Romance.

Basildon’s Depeche Mode entered the charts in ‘81 with New Life. Again, LWT’s Twentieth Century Box caught them in a brief New Romantic phase. Gahan had visited the Blitz, he’d studied window-dressing (the job George O’Dowd was doing on Carnaby Street). But the programme’s real revelation is the audience at Rayleigh’s Crocs.

They’re drawn from a broad social spectrum – one unemployed, another in insurance… and their looks are more extreme than the band. New Romantic style was spreading beyond the cities and into the suburbs. It was everywhere, from Dollar’s David Van Day jacket on TOTP to Razzmatazz’s New Romantic fashion contest for kids (“Steve Strange eat your heart out”).

In the sweltering summer of ’81, the Royal wedding sent the nation into an aristocratic frenzy. Diana Spencer emerged from her carriage with a crumpled, never-ending train like a Blitz kid on a lush budget. Smash Hits likened Ant’s Prince Charming to a ‘royal wedding souvenir’. It contained a New Romantic motto: “ridicule is nothing to be scared of”. Ant, ever-ready to embrace the mainstream, performed that year at the Royal Variety Show.

Dandyism was a double-edged sword; adopting upper-class attire was aspirational yet subversively ironic, mocking the conventions that created them. It was unclear what side of the sword Ant was on.

The squat-dwelling, ostentatiously-dressed Blitz Kids were dandies too, and the mainstreaming of the movement brought similar tensions. Once set in the popular imagination, what had been an ever-changing style froze, now reduced to a few crude garments – pie-crust collars, velvet knickerbockers topped off with badly-applied make-up.

The Princess Julia imperative was “dress fancy, not fancy dress”. Now, as ruffles and frills hit the high street, the look turned panto-pop. You could even buy Ant jackets in the back of Smash Hits – a duplicate, not your own twist.

It was a far cry from the restless, fashion-forward invention of Steve Strange. He’d always preferred ‘the Cult With No Name’ to New Romantics: it suggested a lack of fixed identity. You can’t name a costume that’s constantly changing.

Before you copied his latest incarnation, he’d moved on – to Robinson Crusoe, maybe (tousled, streaked hair, tan, stubble, a blueprint for the mid-80s rocker). Trouble was, this made it hard to classify. Caught between the amorphous leaders and the copycats, the scene began to splinter.

Some dared to bring the tensions to the surface. Especially Soft Cell, No. 1 that summer with Tainted Love. Marc Almond had been enthusiastic in those early New Romantic reports, but Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret offered a darker vision of the grim lives under and away from clubland’s bright lights.

Songs like Bedsitter confronted the realism their peers sought to escape, owing more to the 60s kitchen-sink dramas of Bowie’s London Boy or The Kinks’ Big Black Smoke. Human and vulnerable, daring to show the make-up smudged. The song Youth even contained a warning to ruthless aesthetes: “Beauty is skin deep”. Other outsiders looking in were Dundee’s The Associates.

They shared the New Romantics’ grand themes – 1981’s White Car In Germany was a psychedelic Vienna, while Party Fears Two and Club Country sashayed into the charts like peacocks parading. Listen closer, though, and both describe a night world plagued with dog-eat-dog exclusivity: “Every breath you breathe belongs to… someone there”.

If they weren’t referencing the Blitz specifically, one of its brightest young things was. George O’Dowd, now Boy George, told New Sounds, New Styles that “those Spandau Ballet gigs were fine but the elitism thing is finished. The ice age is over”.

George, now fronting Culture Club, had his sights set on a world bigger than the Blitz and suggested, at the end of synthpop’s biggest year, that futurism, a major New Romantic component, was fading. Spandau were already thawing.

Chant No. 1 came with Beggars and Co. horns and a video shot at Le Beat Route club, soul roots to the fore. By the time of Duran’s Girls On Film TOTP performance, the frills were conspicuously absent, replaced by stripy tees and suits (only Nick Rhodes stayed dandy). At the height of its pomp, New Romanticism seemed already under attack.

Throughout 1982 New Romanticism continued; continued to be harder to pin down and continued to fray. Egan’s playlist hit the mainstream; Kraftwerk had a No. 1 with The Model. He produced a single by a real-life French model, Ronny.

That year, Visage’s The Damned Don’t Cry showed a commitment to the Blitz sensibility, not least in its Midge-directed video, pure inter-war decadence, recalling Dietrich flick Shanghai Express. Midge Ure left that year though to focus on Ultravox. Egan and Strange would continue the group until finally splitting in 1985.

The New Romantics: Cold light of dawn

By 1982, Blitz was gone. Egan and Strange had relocated to Club For Heroes on Baker Street. Former Blitz Kid Chris Sullivan, who ran his own nights such as Le Kilt, would move on to run The Wag Club. The layers that had been woven into the New Romantic fabric were coming apart.

Covent Garden’s Hell had been another Blitz Kid haunt (many of the designers had neo-gothic collections; see Judith Franklin’s black wedding dresses and the ecclesiastical apparel in Ashes to Ashes) but by July ’82 Hell was succeeded by the more overtly Gothic (and anti-New Romantic) Batcave.

Gary Kemp had seen the New Romantics as the true heirs of mod – modernists, unlike revivalists such as Secret Affair or The Lambrettas. After all, a young David Bowie first saw a mod on a train wearing make-up. Perhaps New Romantic is a term that should be redefined more broadly.

It’s a descriptor for pop that was operating in the wake of punk: exploratory, experimental, style-obsessed, mixing old ideas with new technology, ambitious but uncompromising.

Read more: Soft Cell interview

Part of what Malcolm Garrett describes as ’retrievalism’. In this context, ABC’s The Lexicon Of Love, huge that year, was the New Romantic Sgt. Pepper’s. Even the title was suitably heartfelt and self-conscious. Sheffield’s ABC mixed soul boy with glam (mohair suits meets gold lamé), sharp funk with grand orchestras and cutting-edge Trevor Horn productions. On Poison Arrow Martin Fry’s dazzling Ferry-style wordplay even updated Keats… as New Romantic as it gets.

Nevertheless the garish glamour got toned down. The years 1982 and ’83 saw Spandau and Duran trotting the globe sharply dressed in suits. Rio saw Duran shooting videos in Sri Lanka and Antigua, while Spandau recorded True at Compass Point in the Bahamas.

At the height of New Romanticism, Vivienne Westwood’s ‘human mannequin’ Jordan sported an outfit she deemed “perfect for wading through the water in the Caribbean”, the sartorial antidote to Thatcher’s Britain.

But now the likes of Spandau and Duran were pan-global stars actually visiting those exotic locations, they no longer needed outlandish attire to imagine their dreams. They’d achieved them. The body was no longer a canvas for artistic aspiration, but jet-set affluence. Even New Romantic’s father Bowie returned in ’83 with Let’s Dance, glowing healthily in a suit not too dissimilar to Simon Le Bon’s.

Of course, none of this applied to Boy George. Icy electro was out (’82’s chart-topper Do You Really Want To Hurt Me? was more Lover’s Rock than Kraftwerk) but the lip-gloss and pick-and-mix approach stayed. Culture Club conquered America with the help of MTV. Others hit big there too, including A Flock of Seagulls. The Blitz Kids, and the New Romantics, it seemed, had armed a generation with the panstick and eye-liner for a Second British Invasion.

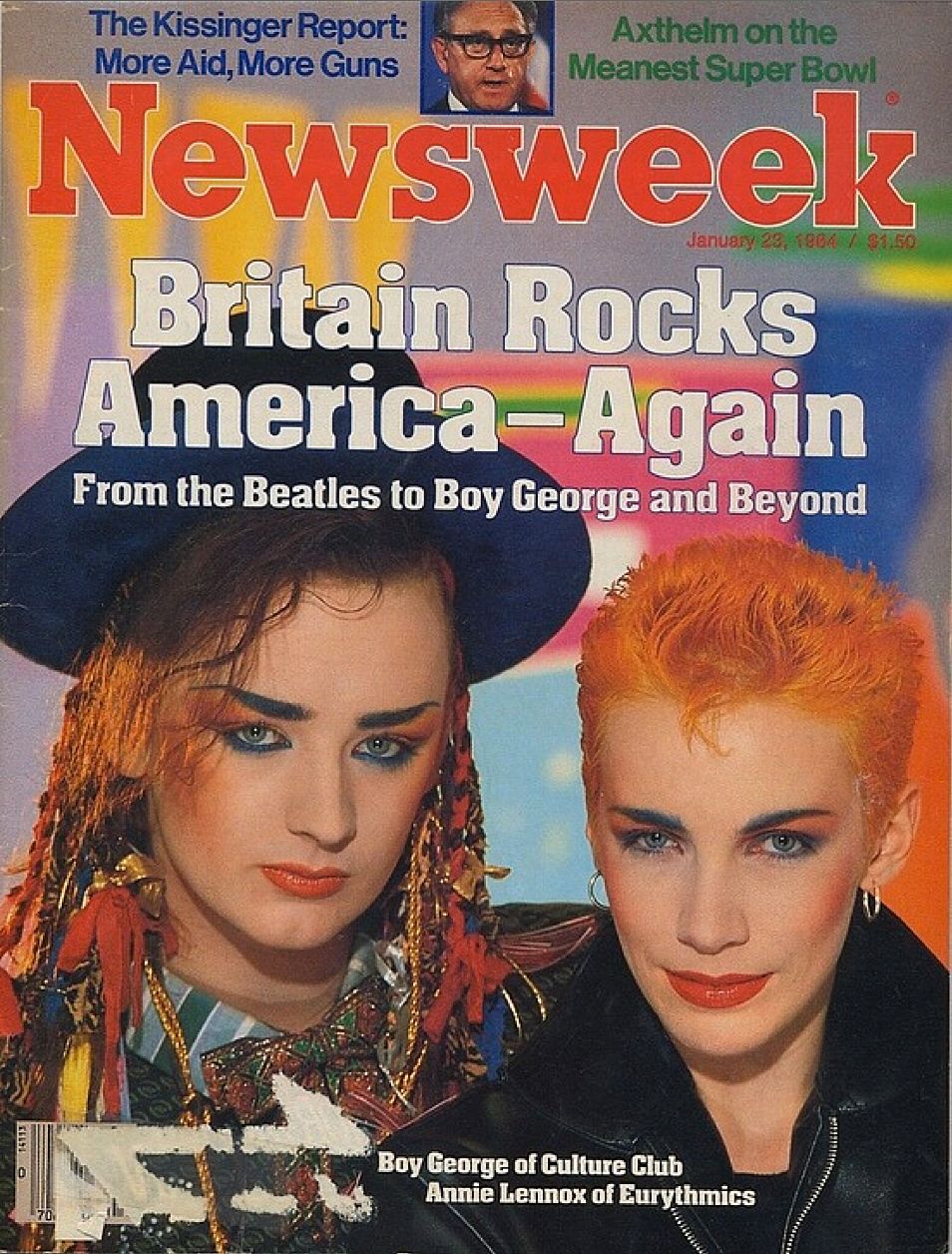

Newsweek even gave George a cover with androgynous co-star Annie Lennox. Eurythmics had mixed dandyism and ‘executive realness’ in the Sweet Dreams promo, and featured Marilyn in the one for Who’s That Girl? Lennox hid behind highwaymen masks on Sweet Dreams and Touch’s sleeves – signs that the New Romantic spirit lived on (see Lipstick Traces on the following page).

It rubbed off on the America Boy George had seduced, too; George argued Prince’s mainstream success would have been unlikely without his trail-blazing. Then there was Madonna, the Stateside Blitz Kid incarnate (Egan even remixed Everybody). By the mid-80s her ‘Wannabe’ Monroe persona took Marilyn one stage further.

The New Romantics

Throughout the rest of the 80s New Romanticism persisted and struggled. Looks toughened and realism returned. The Hard Times look was a riposte to the New Romantics’ florid garb. Wham sported street clobber, rapped about the DHSS. When gay pop peaked in ’84, it was lusty and leather clad (Frankie) or dressed down and political (Bronski Beat).

Strange had ‘done’ a Frankie first with the Wild One-style Pleasure Boys clip back in late ’82. By the time the AIDS epidemic hit Britain, Blitz’s gender-blurring, homo-hetero mingling seemed a world away. Boundaries came back up as gay culture’s hyper-macho streak took centre-stage in the face of the disease.

Besides, the Hi-NRG sound required less clothing, not more. Dressing as Henry VIII wasn’t an option. The same applied to clubbing in general with the advent of E and rave.

Major labels and stylists took control of pop, thwarting New Romanticism’s unique, independently-minded glamour. By the end of the decade, Stock Aitken and Waterman dominated British music. Their stars were everything the Blitz Kids had refused to be; boys and girls and next door.

Flashes of outrage and colour flared up briefly, often supplied by O’Dowd’s old friends (such as Degville in Sigue Sigue Sputnik). Yet the Blitz Kids’ synergy between music, fashion and clubbing had an everlasting impact. And if the New Romantics were ‘people taking pictures of people taking pictures of them’, then this much is true: we’re all Blitz Kids now.

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.