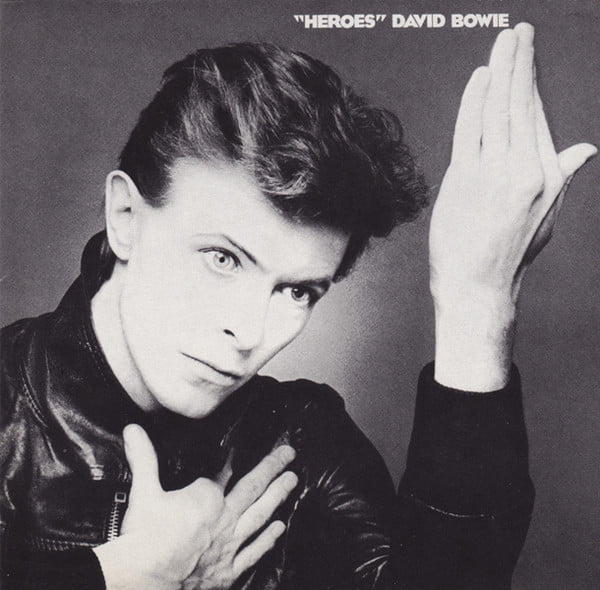

Making David Bowie: “Heroes”

By Andy Price | December 13, 2021

Following Low, David Bowie: “Heroes” was the singer’s triumphant love letter to Berlin…

Though Low’s later instrumentals referenced various facets of Bowie’s newly adopted home of Berlin, as a whole, it was a much more internalised affair which, for at least half its running time, served as an exercise in self-reflection through music.

“Heroes”, released in October 1977, would be a much more comprehensive study of the city that had given him succour, and Berlin had certainly done that for Bowie: socially, culturally and musically.

Bowie regarded Berlin as “the centre of everything that is happening and will happen in Europe over the next few years”, a sentiment he shared with Vogue in 1978.

For him, Berlin wasn’t just an environment on this record. It was a character in its own right, brought to life as vividly as Ziggy, Aladdin Sane or the Thin White Duke.

Bowie’s life in West Berlin – living with Iggy Pop, frequenting bars, consuming art, culture and consistently creating music – was constantly and quite literally overshadowed by the presence of the wall: a looming totem of oppression that underlined the tense Cold War paranoia of the time.

Bowie injected many of the album’s tracks with the feel of unease he experienced in his new home, although primarily from a more personalised perspective.

There was also the more obvious influence of the krautrock and Germanic bands that had caused David to explore these new sonic highways in the first place; they too are referenced (both lyrically and sonically) on “Heroes”.

Bowie explicitly repaid his debts to Kraftwerk on V-2 Schneider (they had namechecked him on their influential Trans-Europe Express) and to Neu! with the album’s title itself – which serves as both a statement and nod of acknowledgement to the German band’s 1975 track, Hero.

Like Low, the album is lyrically fragmented. However, in place of that record’s more isolated tone, “Heroes” stresses togetherness.

From Beauty And The Beast’s defiant, obstacle-bounding couple, to the title track’s stirring image of kissing in the shadow of the wall, to the more sinister collective of Sons Of The Silent Age: being alone is no longer a principal lyrical theme.

The victorious tone of the stellar title track can perhaps be partly attributed to Bowie’s conquering of one of the lingering demons that he sought to confront on the previous record: his cocaine dependence – which at this point, though not entirely vanquished, had at least been severely reduced.

The synthesiser contributions of Bowie’s avant-garde copilot Brian Eno would continue to be an important part of Bowie’s working practice, as would Eno’s curious artistic directions to the other musicians via his ‘Oblique Strategies’ card set (eg, “Honour thy mistakes as hidden intentions”).

Together, they’d emulate the existing template established on Low (that of ‘songs’ on Side One and instrumentals on Side Two). These instrumentals would be much more cohesive, subtler and in some respects, more successful, fusing synthesis with sound effects and live instruments. Tony Visconti also returned – not only as the album’s (oft underrated) producer, but as a vital creative contributor.

Read more: The alternative David Bowie Top 20 – 1975-’80

Read more: The alternative David Bowie Top 20 – 1981–’93

His intelligent use of gated mics enabled Bowie’s stellar vocal performance on the title track to be captured in one take, with Bowie intuitively raising the intensity.

Though the album discards the funkier arrangements found on Side One of Low, Carlos Alomar, George Murray and Dennis Davis (dubbed The DAM Trio) were still central to the record’s sound. The addition of King Crimson’s Robert Fripp added a touch of the dementedly histrionic to proceedings, which could occasionally veer into the utterly transcendental.

The spikier arrangements on tracks such as Joe The Lion and Blackout pushed the envelope and would serve as a blueprint for many post-punk artists, while the more mechanical, industrial tone of Beauty And The Beast and V-2 Schneider would further illuminate the ‘Motorik’ sound of krautrock – replicated a scant few years later in the UK by Gary Numan and others.

Following the occasionally harrowing instrumental suite on Side Two, the album concludes with the incongruous The Secret Life of Arabia – a track that, when listening to the trilogy in order, serves as a stepping stone to the more geographically diverse Lodger, but also comes as idealised relief from the grim soundscape that preceded it.

Alomar himself told us that he remembered when David first brought the shell of “Heroes” (the song) into the studio: “It was just two chords,” Alomar recalled. “David got on a piano and started playing them, ‘dun dun dun dun, dun dun…’ et cetera. That’s basically the way it is. It was very basic. I’m thinking like a jazz guy and we don’t really have keys, we were like, ‘okay, that’s ‘one’, let’s go to ‘four’’, so we’d speak like that. This gave us a neat way of moving forward.

“David and I were always concerned with creating a signature line, and pretty much every guitar part that I’ve come up with has always been under the umbrella of that. The DAM Trio came up with the chugging rhythm and the Motown bassline.

“That became the whole song, once we added that little signature phrase it all clicked into place. The issue of the lyric, of course, was important to David – “Heroes” and the city of Berlin had a very special meaning to him.”

Read more: David Bowie in the 90s

Read more: Making David Bowie’s Let’s Dance

Indeed, “Heroes” is now regarded as one of Bowie’s finest albums. Although critical evaluation often favours Low as the pinnacle of the Berlin Trilogy, “Heroes” is very much the authentic ‘Berlin’ album.

It’s the perfect encapsulation of Bowie’s love for the city, injecting into his songwriting his impressions of the social upheaval that the city’s post-war structure had created, the lingering tension between West and East and also the personal and social relief the city had provided him as an individual.

It’s technically magnificent, featuring an innovative, almost painterly use of guitar, synth, effects, rhythm and vocals that would further the exploratory work begun on Low, and would influence future generations of musicians. As a listening experience, it’s arguably more consistent than Low and ranks very highly among David Bowie’s greatest work.

David Bowie: “Heroes” – The Songs

Beauty And The Beast

Unlike Low’s rapid fade-in, a tense, time bomb of a build-up whirrs “Heroes” to life – with a sound akin to a power generator starting up. Bowie’s ghostly “oooh” emerges from the sonic ether and suddenly, we’re into the song proper – a peculiar, rhythmically jerky track that lyrically alludes to slaughter, protest and defiance.

It’s notable for its processed guitar sound, the foregrounding of “Heroes” lead player Robert Fripp and the tight, swerving dexterity of the DAM Trio.

The song is often read as a reflection on Bowie’s Thin White Duke phase and the shedding of the negative influence the character had on him, though Bowie himself never discussed the song’s lyric. It was an unusual choice for the record’s second single, one which NME’s Charles Shaar Murray would describe as: “One of the most menacing singles of a menacing year”.

Joe The Lion

A chaotic, often (effectively) mistimed series of web-building guitar riffs burst out of the dark before stabilising into Joe The Lion’s verse, allowing Bowie’s impassioned lyric of dedication to extreme performance artist Chris Burden and the wider implications of ‘living your art’ to take centre stage. It’s one of the album’s most arresting moments, and the peculiarly chaotic arrangement goes hand in hand with the decadent mentions of having a “a couple of drinks on the house”. Bowie’s lyrics were allegedly assembled at the mic while listening to the first mix of vocal-free music – an approach he adopted from Iggy. The flat delivery of “It’s Monday” during the track’s breakdown was indeed ad-libbed live because, well, it was Monday!

“Heroes”

Not just the best thing on this record, the widely celebrated title track – for our money – is one of the greatest pieces of music ever recorded, by anyone. On the majestic “Heroes”, everything that Bowie sought to achieve during this period comes to perfect fruition. Firstly, there’s the foundation of Bowie’s piano chords which, as Carlos Alomar tells us, was gradually layered and built over time. George Murray’s supportive, almost soul-like walking bassline is counterpointed by Alomar’s higher octave melodic bolstering. The serene beauty of Robert Fripp’s Eno-processed lead riff surfs this wave with an elegant grace, while both Bowie’s lyrics and vocal performance are among his finest on record.

The wonderfully moving lyric tells the emotive story of a couple’s potentially doomed relationship in the face of many insurmountable challenges (not least the Berlin Wall) from the one-sided viewpoint of the male protagonist whose repeated refrains of “just for one day” are as bittersweet as they are triumphant. Bowie’s dramatic delivery makes these lyrics all the more affecting.

Bowie is believable as the lyric’s protagonist who “drinks all the time” and painfully remembers the triumph of kissing his partner by the wall while the guns shot above their heads. There’s such a range of interpretations and resonances one could take from this superb piece of music, yet it works, first and foremost, as an absorbing, well-constructed piece of sonic art. You don’t need us to tell you that it’s one of Bowie’s finest songs.

Sons Of The Silent Age

There’s something familiar about Sons Of The Silent Age: the shadowy cabal who “glide in and out of life” and “never die, they just go to sleep one day” brings to mind earlier compositions, in particular the similar beings that stalked 1970’s The Supermen. Considering Bowie’s current location, his allusions to making war and the somewhat fascistic subtext of the lyric, Sons Of The Silent Age is altogether darker and less fantastical, despite its weirdly ‘cheesy’ arrangement on the chorus and dreamy, surreal verse. Bowie’s sax playing here is a central element of the mix and his accentuated delivery of the vocals would influence many copycats in the wake of the album’s release.

Blackout

A musical sister piece to Joe The Lion, Blackout rounds out the first side of “Heroes” with a mix swamped by Eno’s insistent synthesiser and Fripp’s almost painfully high-register guitar work. Like Joe…, Blackout is rush of sonic inebriation that complements Bowie’s confused, frenetic lyric. The reference to blacking out perhaps refers to a visit from the then-estranged Angie the previous year, a fraught affair that resulted in a depressed Bowie drinking too much and, indeed, losing consciousness (this would also explain the “someone’s back in town” lyric). Bowie’s insane vocal delivery is really the track’s most notable element. Bowie goes from baritone vibrato to high-register screams of desperation and panic with ease. It’s a wonderful listen, though perhaps born from a dark place.

V-2 Schneider

Side Two’s instrumental section begins with V-2 Schneider – a marching, militaristic tribute to both Kraftwerk and a reference to the Nazis’ V-2 rocket (and a fusion of the two, as Bowie would later say that Kraftwerk’s influence was akin to that of a V-2 rocket hitting him). The circular, infectious rhythm is explored by Bowie’s assertive sax performance, while his vocal delivery of the song’s title was run through what Visconti later described as a “cheap little synthesiser” to only leave the vowel sounds audible (“ee-oo-i-er!”).

Sense Of Doubt

This three-track suite of naturally flowing instrumentals begins with a composition dominated by an ominous crescendo of four descending notes, an evocation perhaps of the military domination of Berlin, while the threads of eerie synth strands that hold the oppressive piano notes together seem so deliberately small in comparison. There are all kinds of subtle sonic textures hidden within this rich mix, as well as occasional washes of Eno’s colourful synth and scattered hints of former glory with the occasional fragments of melody. It leads organically, via a sound effect of howling wind, into…

Moss Garden

A moment of respite from the ghoulish wasteland established at the end of Sense Of Doubt, Moss Garden serves as an interesting oriental deviation – taking its inspiration from the Moss Garden in Kyoto – then a potential candidate for Bowie’s next home. The gentle serenity makes it work perfectly in context, as a dreamy bridge between the dark instrumentals that sandwich it. The koto (a Japanese classical instrument) is played by Bowie himself and helps establish the track’s air of dreamy distance.

Neuköln

Winding out of Moss Garden, the listener is awoken sharply by the distant siren of a high-register synth, before Bowie’s skittish sax once more emerges and chillingly leads the arrangement. Neuköln was partly inspired by the struggles of the Turkish community in the area of Berlin where Bowie lived at the time, and the Eastern musicology of the track reflects that. Once again, the mix is sprinkled with fascinating sonic moments, resolving into an unnerving saxophonic death throe. It’s a provocative instrumental, and one which rewards repeated listening. Indeed, the best way to experience this piece is in the context of the previous two tracks on the record, as the finale of one long instrumental feast for the ears.

The Secret Life Of Arabia

The album’s epilogue is wildly different from anything else on the record, and paves the way towards the final piece in Bowie’s ‘triptych’ – Lodger. We’ve also backtracked, in some respects, to the funkier sound of Station To Station, while Eno contributes some effective synthesiser to rein the track into broadly the same sonic universe as the rest of the parent album. The lyrics blur the lines between reality and cinema, with references to crossfades, and “the heroine”, as well as direct reference to “the movie” (Lawrence Of Arabia perhaps?). It’s a perfectly enjoyable track, with both interesting lyrics and a Latin-infused arrangement that ends the album with a feeling of hopeful optimism.

Read more: Top 40 New Romantic songs

Did you enjoy this article on the making of David Bowie: “Heroes”? Then check out our feature on Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)