Interview: Richard Coles remembers the Communards

By John Earls | December 3, 2024

After more than a decade as TV’s go-to vicar, it’s easy to forget how influential Rev Richard Coles was alongside Jimmy Somerville in political pop mavericks Communards.

It seems a long way from Don’t Leave Me This Way to the pulpit, via hedonistic abandon in Ibiza, not least for the man who lived through it all. As Communards’ music is reissued, the Vicar of Finedon tells us: “It feels like I was a different person then.”

“If my CV landed on my desk with a job application, I’d think it the work of fantasy. But it is what happened.” Trying to make sense of how he went from teenage runaway to Britain’s most famous vicar via Top Of The Pops – and being so off his nut on drugs that he tried buying an aeroplane while shirtless in Ibiza – Rev Richard Coles smiles gently at the rich life he’s led.

It’s a famous part of his story in becoming the vicar of the quiet Northants village of Finedon that Richard was once a pop star. What’s been obscured in the 33 years since Richard and Jimmy Somerville split is just how controversial and trailblazing Communards were.

Infiltrating The Mainstream

In the fallout from Jimmy’s equally explosive previous band Bronski Beat, Communards were political from the outset, socialists who, in Richard’s words, “tried to bring down Margaret Thatcher with disco and supper-club jazz.”

They didn’t quite succeed, but they smuggled left-wing politics into the mainstream via huge singles including Don’t Leave Me This Way and Never Can Say Goodbye, describing their ideologies in Smash Hits while also trying to cope with the ravages AIDS was having on the gay community. It seems another universe from Sunday sermons and appearing on QI.

“It’s weird to think Communards’ first album was 35 years ago,” ponders Richard. “Nothing in my life feels like it could have been so long ago as 35 years, but in other ways it feels I was a different person then.”

Since Communards’ final single There’s More To Love in 1988 kept up an unbroken run of nine Top 30 hits, Richard almost immediately gave up pop music. “I did string arrangements and tried writing with a female singer,” Richard recalls. “But it didn’t work for me, because being a musician was a moment in my life that came and went. It was never something I’d particularly wanted to do. Being a musician was never the fulfilment of a dream. I got interested in other areas of life.”

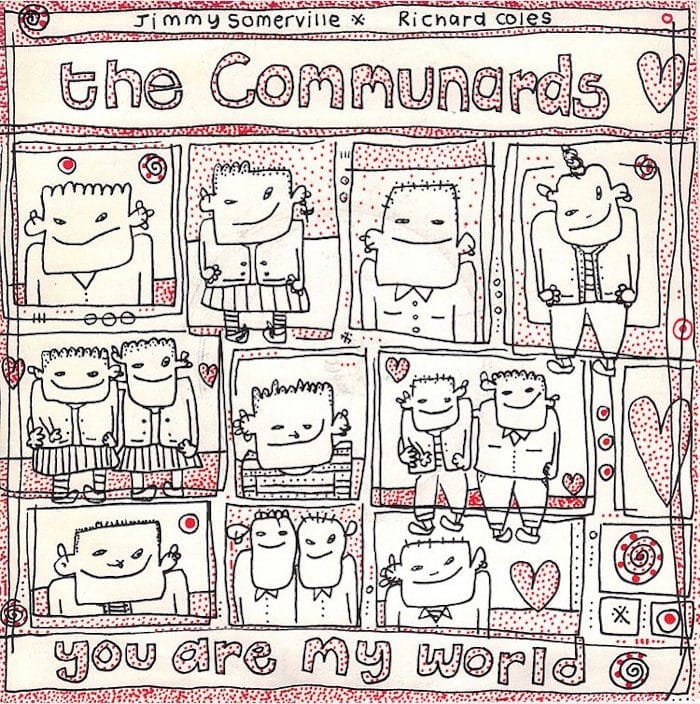

You Are My World

Richard’s late husband David “found it quite ridiculous” his spouse had ever been in a band. “I don’t think David ever saw anyone who was more vicarish than me,” laughs Richard. “He liked Communards’ records, but he laughed at the thought of me being in a pop group.” Of course, Richard sings at sermons. He learned the accordion in lockdown after a parishioner left him one in their will, making his accordionist debut in September at a local fete. Trailblazing pop star, though? That was another life.

A deluxe reissue of Communards’ self-titled 1986 debut album has jolted Richard into revisiting just what he and Jimmy achieved, both musically and socially. “I’m very proud we pushed the boundaries of inclusion,” reflects Richard. “We helped to make Britain a more diverse, inclusive and better place. Victories were gained in that fight which have become consolidated. Gay marriage is nothing remarkable now, which is really good.”

Pushing The Boundaries Of Inclusion

Named after 19th century French revolutionaries, Communards were out to agitate from the start, intended to be more explicitly political than Bronski Beat. Richard had known Jimmy before Bronski Beat began, friends since meeting in the gay scene among London’s squats in 1982.

Richard and Jimmy had both run away from home to London, though the keyboardist is quick to point out their upbringing was otherwise poles apart. “We liked each other because we were such opposite people,” Richard reasons. “Jimmy came from a tough working class background in Glasgow, while I was a public school educated Englishman from Kettering. We enjoyed the differences in each other.”

Despite being instant friends, Richard didn’t become part of Bronski Beat, revealing: “Jimmy never had a masterplan. Steve Bronski and Larry Steinbachek, the other guys in Bronski Beat, lived in the same block as Jimmy. He’d have had to cross the Thames to get to me, which was too much of a commute.”

The Revolution Will Be Televised

Richard was delighted when the trio took off, remembering: “When I first heard Jimmy sing, it was so exciting. Jimmy has a very gruff Scottish speaking voice, so you’d never guess how he sings. I thought, ‘This is extraordinary!’ Stood in front of me, Jimmy arrived as this fully formed singer with limitless potential. He’s not just a technically great singer, he can distil in his voice the experiences of so many people. Bronski’s first Top Of The Pops appearance for Smalltown Boy was a magic moment, realising the world was suddenly seeing and hearing what I had.”

Bronski Beat’s diverse personalities made for an incendiary experience, and Jimmy soon invited Richard to play saxophone on tour, largely to have a friend with him. “Jimmy had a tough time growing up,” Richard explains. “In London, Jimmy had gathered around him a tight group, and for the first time he could lead the life he wanted. But success takes you away from those things and success was tough for him.”

Don’t Leave Me This Way

It became more comfortable for Jimmy to quit Bronski Beat and start Communards with his friend. “Fame wasn’t as distant from the world I knew as it was for Jimmy,” says Richard. “Success was exhilarating for me, and so was the money. What I wasn’t prepared for was my own surging need for validation. Jimmy was so spectacularly talented that I sometimes struggled around his brilliance. That’s absurd, as I got a better deal than Jimmy did. Singers get the glory, but we instrumentalists are allowed to change as people more readily.”

Although in the long run Richard was more easily able to move into different areas of life than his bandmate, at the time Richard felt slightly hampered in his songwriting. He’s well aware that Communards’ biggest singles were both covers: Don’t Leave Me This Way by Harold Melvin & The Bluenotes, while Never Can Say Goodbye had been a Jackson 5 hit.

“Those singles have an immediacy that my own songs didn’t have,” sighs Richard. “I’d love to have been a better songwriter, but I just wasn’t. I was rather vampiric about using Jimmy’s voice. I was a middling pianist who could bring some tools to what we did, but Jimmy was the one with the gift. Communards’ records are great, but Bronski’s album The Age Of Consent captures something and I wasn’t up to that.

Sound Of Liberation

“We did those covers because we were gay men of a certain age, where dance music wasn’t just entertainment, it was the sound of liberation. Those singles were political for us. That needn’t necessarily be the case for people listening, and that’s OK. They still fill dancefloors. And both our albums still sound very accomplished, but that’s probably our producer Mike Thorne’s doing.”

The new edition of Communards includes the duo’s own epic 12-minute remix of Don’t Leave Me This Way with Mike Thorne, made under the alias of Gotham City. “That remix is my favourite piece of music I ever made with Jimmy,” Richard enthuses. “We were in New York, in our early twenties and we had time to throw the kitchen sink

at this song that meant a lot to us. So we did.”

Communards’ tours, with an otherwise all-female band, were a riot: “Jimmy and I are fairly St Trinian’s as people, and those tours were like living in a St Trinian’s film,” says Richard. “When we arrived in town, it’d be a big party. I still have friends throughout Europe who I met on those tours.”

Opposites Attract

Trying to enjoy success was tainted by the shadow of AIDS. The disease had begun to have a huge impact among gay people while Communards were starting. The duo’s friend, political activist Mark Ashton, died in 1987.

“We were in Spain when we got the news,” remembers Richard. “We were literally about to go on stage for Spain’s version of Top Of The Pops when I took the call. It was just a bizarre moment. It’s only the last few years that I’ve felt able to talk about AIDS. There’s evidence that there’s a 30-year period between a traumatic experience and being able to talk about it. Speaking with close friends, we’ve realised we were deeply marked by AIDS and that we’ve never fully dealt with it.”

It was understandable that the opposites of Jimmy and Richard’s personalities that initially made them friends began instead to separate them. “Those differences which made us interesting also militated against us,” Richard confirms.

Fiery Feelings

Speaking to Classic Pop in 2015 around his album Homage, Jimmy explained he was so troubled by fame that he hated his own music for many years. It’s a revelation that doesn’t totally surprise his former bandmate. “Jimmy is a man of intense passions and fiery feelings,” notes Richard. “Pop stardom amplifies that. Just being around Jimmy could create stormy weather, and standing on stage was even more stormy for Jimmy. He surprised himself with his own turbulence.”

After just three years, it was time for Communards to end. “I don’t think we understood each other,” Richard confesses. “Our lives were so different, we didn’t really have the tools for finding our way through disagreements. It was obvious we had nothing left to give each other. We never actually split up, though. We just decided to stop for a while. It’s a pause that’s lasted 33 years.”

Flying High

The transition from pop to religion seems smooth in retrospect, but Richard needed time to decompress from pop stardom first. Or he just decided to get even wilder and party for a couple of years. In Ibiza in 1990, he was with a group of 20 friends when his most hedonistic moment occurred. He remembers: “We were just ridiculous. We’d take loads of ecstasy and stay up all night dancing.

“We tried to buy an aeroplane, but the authorities wouldn’t let us, as we were shirtless at the time. There’s a tip for your readers: if you’re going to buy an aeroplane, wear a shirt. So instead, I bought a speedboat. We had a high old time in that, but then I forgot where I left it. I assume it’s still rusting away in a cove in Ibiza. Or maybe it’s being used for drug smuggling. It’s a good title for an album: Has Anyone Seen My Speedboat?”

Jimmy admitted to Classic Pop he was initially angry that Richard had become involved in organised religion, a revelation that touches Richard. “Credit to Jimmy if that’s how he felt,” he ponders. “I didn’t know that, as personally Jimmy was always very supportive. I was very grateful to him for that.”

Never Can Say Goodbye

Having been Finedon’s vicar since 2006, it’s clear religion is a more suitable life for Richard than itinerant pop star. His pop life is summarised with a typically esoteric Richard Coles story. “I talked to a mercenary who fought in Angola recently,” he begins, the kind of experience that only seems normal for Rev Richard Coles. “I felt a certain affinity with him. We’d both had this incredibly vivid experience for a short while. Being a pop star was something that I dropped into and then out of, which was so unusual it feels separate from the rest of my life.”

Would Richard ever want to repeat the experience with Jimmy, maybe as a one-off show to definitively end that 30-plus pause? “I miss the excitement of Jimmy’s voice,” Richard considers. “But the usual reason for bands reforming is a tax investigation and, mercifully, I don’t think I have any outstanding matters with HMRC. I wonder how I’d feel if a good offer came along, but I don’t think I’d remember any of the songs. Some things are best left as they are.”

Forget any professional incentives, its a personal closure that would really interest Richard. “Communards was something we went through together uniquely as equal partners,” he says. “I’d love to see more of Jimmy, because reflecting on what happened is a conversation I hope we have one day.”

Visit Richard Coles’ website here

Read More: Classic Pop’s Top 20 80s pop duos