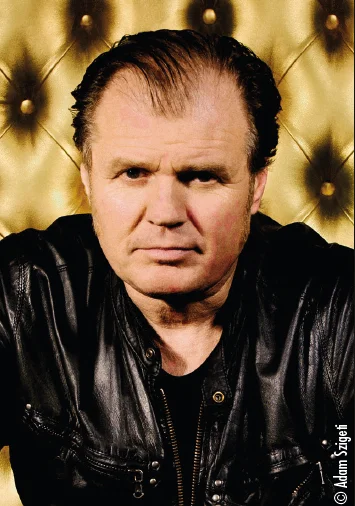

ABC: Martin Fry interview

By Paul Kirkley | March 22, 2022

As he prepares to mark the 40th anniversary of The Lexicon Of Love with a lavish new live tour, accompanied by Anne Dudley and the Southbank Sinfonia, Martin Fry tells Classic Pop how ABC set about creating a timeless pop masterpiece…

When Martin Fry steps onto the stage at Sheffield City Hall in June 2022, it will be exactly 40 years to the day since the release of The Lexicon Of Love – the landmark pop classic that exploded like a musical glitterbomb from the Steel City’s grey, post-industrial landscape.

“That’s going to be an emotional evening, I know it is,” says Martin, when Classic Pop catches up with him over Zoom. “It doesn’t feel like 40 years. A lot happens in four decades, doesn’t it? But I have no regrets. It’s been a life well lived.”

Without The Lexicon Of Love, it’s fair to say Martin would probably have lived a very different life over those four decades…

“I guess so,” he considers. “This is the George Michael question, isn’t it – what if I’d turned a different corner? It stopped me being a lot of things [this record] – I could have been an airline pilot or an astronaut! But you can’t think that way. It’s been very good to me, The Lexicon Of Love. But I’m just a custodian – as soon as you make a record, it becomes public property. It goes off into the world.”

A critical and commercial hit right off the bat, The Lexicon Of Love’s reputation has only grown over time: it’s a regular fixture in lists of all-time greatest British LPs, and it’s no accident that Classic Pop chose it as our first Classic Album, way back in issue one.

To understand how such a lustrous pop gem emerged from the wintry first chill of Thatcher’s Britain – in a year when unemployment topped three million for the first time since the Great Depression – we have to rewind to late-70s Sheffield, where Manchester-born Martin David Fry was combining his university studies with editing a music fanzine called Modern Drugs.

After interviewing Stephen Singleton and Mark White, of local electro outfit Vice Versa, Martin was invited to join the band, which by late 1980 had evolved into ABC, with Fry as its lead singer.

Read more: ABC’s Forget Me Nots: ABC – How To Be A …Zillionaire!

Read more: Making The Lexicon Of Love

With a Top 20 single, Tears Are Not Enough, already under their belt, ABC set about making their debut album with a bold and ambitious vision designed to inject a shot of shimmering, Rat Pack glamour and bruised romance into a world of dole queues and Protect And Survive leaflets.

“At the core of it was a mentality that said, ‘Right, we want to take on the world,’” recalls Martin. “We were saying: ‘Pop music is this. It’s polished, it’s emotional, it’s going to compete with Cole Porter and those guys. Forget The Beatles, we’re ABC!”

It was, says Martin, a very deliberate and defiant reaction to the times, and to the band’s personal situation. “We were bohemians jumping on the bus – you could go anywhere in Sheffield for 10p in those days. I lived in the Hyde Park flats, and a night out was sitting in a pub full of blokes playing dominoes. There weren’t too many exit routes.

“I used to share a house with a guy called Disco John, who was the DJ at Penny’s [nightclub]. He’d tape Hollywood movies and show them. The glamour! The glamour came in small chunks back then. There were only three TV channels, we’d never heard the concept of 24/7…

“We wanted to separate ourselves not only from the world of rock and roll and leather trousers, but also from Sheffield,” admits Martin, of the city’s fabled reputation as the spiritual home of new wave synth-pop. “There were incredible bands, obviously, like Cabaret Voltaire and The Human League, Clock DVA, Artery, I’m So Hollow… There were so many great acts, so you had to sort of define yourself rigorously. I think that’s where a lot of the whole romantic, Sinatra thing came from.

“Destroy, disorder, disorientate – I think a large part of being in a band is provoking a reaction. And the Sheffield scene hated us. Vice Versa were probably the most hated band in Sheffield. It was a very competitive scene – you’d play a show at the George IV and the whole audience was people in bands. It’s the worst audience you can ever play to. Playing the Hollywood Bowl was a breeze after that!”

To help realise their vaulting ambition, the band approached producer Trevor Horn, whose stock was soaring after the success of The Buggles’ Video Killed The Radio Star, which he’d followed by producing a brace of hit singles for Dollar.

“I met Trevor in a pizza parlour at the bottom of Queensway [in London] and you could tell he immediately liked what we were talking about, the way we were fantasising about the record we were going to make,” says Martin. “Which is a big part of making records – the self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Though the band’s vision of combining punk and new wave with funk and disco seems brilliantly obvious in hindsight, it was something of a gamble at a time when, in some quarters, disco was still a dirty word. “We were trying to fuse two worlds,” Martin explains. “The worlds of Chic and Earth Wind & Fire with The Cure and Joy Division; Black music with white music.”

From the start, the band envisaged embellishing their electronic arsenal of Fairlights and sequencers with strings and brass. “We wanted something big,” says Martin. “We already had a horn section [Stephen Singleton’s sax], but we didn’t have the budget for strings. Getting Phonogram to put strings on the record – we had to fight for that every single step of the way. But it was a big part of it – it was in that tradition of Philly Soul. And Motown, I suppose.”

With 25-year-old composer, musician and future Oscar-winner Anne Dudley taking charge of the orchestral arrangements, second single The Look Of Love showcased the album’s mash-up of Sheffield electronica and symphonic grandeur, with soaring strings underpinned by a funky Moog bassline.

“I remember Anne saying, ‘I’ll go home and score it tonight’, and she came in the next morning and it was done,” says Martin. “Although when Trevor said he wanted a full orchestra on All Of My Heart I said, ‘Well hold on here – are we going to go full treacle?’ To which Trevor said, ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water had strings on it…’ And I really liked Hall & Oates, which has got that tradition, so…”

Recorded over three months at Sarm East and Abbey Road studios in London, The Lexicon Of Love entered the UK charts at No.1, and hung around for the best part of a year. “[Lead single] Poison Arrow was a hit, and then as each week went by, we became more and more popular,” recalls Martin of those heady days in the white glare of the pop spotlight.

Martin played the role of a suave pop star perfectly, though, even parlaying The Lexicon Of Love’s James Bond glamour into a feature-length musical spy pastiche, the Julien Temple-directed Mantrap. “We were also one of those bands that had a foot in the kind of world of Smash Hits, and a foot in the world of NME and Melody Maker,” he notes.

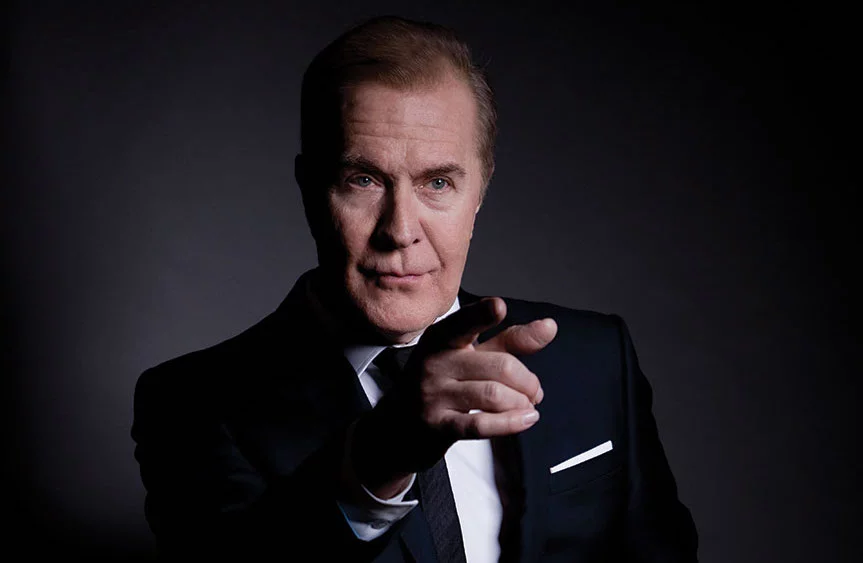

Today, as a trim and impossibly youthful 63-year-old (“smoke and mirrors”, he grins), Martin looks as sharp as ever in his trademark gold lamé suit. “There were three suits originally,” he explains. “A couple of them got stolen. One got left in Japan. And I’ve got one for the V&A. That’s my pension – it can go next to Adam [Ant]’s highwayman outfit. [Savile Row tailor] William Hunt made me the most recent one. We’ve tweaked it a couple of times.”

In 2022, Martin will be slipping back into the lamé and taking The Lexicon Of Love on the road for its 40th anniversary, performing the album in its entirety – plus choice cuts from the ABC catalogue – with the Southbank Sinfonia, conducted by Anne Dudley.

“Have you noticed there’s an entire music industry devoted to anniversaries now?” he smiles. “It’s a great excuse to play some shows, basically. We played at the Royal Albert Hall with the orchestra [in 2009] and it just felt right. That’s what inspired me to start recording [2016’s follow-up album] The Lexicon Of Love II.”

Numerous artists have given their classic albums an orchestral makeover in recent years – but few feel as naturally suited to it as The Lexicon Of Love. “It’s how you do it,” says Martin. “You can trowel it on and dial up a million violins but… This is a show that’s kind of developed over the years. We’ve changed the running order slightly – the purists do get a bit upset with that.

“But it’s great, the scale of it works. I was a bit concerned I might get lost in the proceedings but that never happened. You want the show, and the songs, to come alive in the present age. You can’t just say, ‘Well they were great back in 1982, please use your imagination.’ When people buy tickets, they want to see something spectacular.”

For all that The Lexicon Of Love has been good to him, have there been times when Martin has wanted to escape the long shadow of his debut album?

“For many years, I used to call it our Citizen Kane,” he says. “And I really like The Magnificent Ambersons! And Touch Of Evil, that’s another great Orson Welles film.

“In a way, we wanted to be like Michael Jackson, Prince and Madonna – more bulletproof, with hit after hit. But The Lexicon Of Love is kind of our calling card. The public demands that we play it, and it’s fun to perform those songs. I mean, [1985’s How To Be A… Zillionaire!] sold more in America, and [1987 single] When Smokey Sings was a big hit there, too. I’ve been fortunate to have lots of hits.

“We’ve had some failures, too, of course. It’s funny, now, in the Spotify age, people kind of look at your whole career – the commercial highs, the commercial lows, but also just from an artistic perspective, so it’s kind of nice. But no, I encourage the idea that The Lexicon Of Love is a classic, because it allows me to do all sorts of things.”

All pop careers have their ebbs and flows, to say nothing of the personal bumps in the road – including, for Martin, being diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1986. But he strikes CP as a man who, on the whole, has enjoyed the ride. “Being a pop star is great if you can define it,” he suggests. “If you own it. When you become successful in your early twenties, there are a lot of people trying to tell you what to do, and I never really responded to that, sadly. I never liked being told what to do. I think that’s where a lot of our greatness came from, and it’s also where a lot of our problems arose.

“But I’m also… is thankful the word? I feel really good about today. Over the last 10, 20 years I’ve played some incredible shows around the world. You really can’t buy that feeling, when you walk out and people are singing those songs you’ve written.

“I kind of went indie for a while in the 90s,” he says. “I went back to playing small theatres. And I went to Ibiza, playing at three in the morning.”

And then along came the 80s revival movement – the Here & Now package tours and Let’s Rock festivals that offered audience and performers alike the chance to recapture something of their lost youths. “The 80s nostalgia circuit has now been running longer than the decade itself,” he notes with a smile. “We’ve just played a bunch of Let’s Rock shows with Adam Ant. To go out into a field where there’s 20,000 people singing All Of My Heart right back at me… That’s kind of more fun than you’re allowed. That ain’t bad.”

In recent decades, Martin has been sailing the ABC ship alone. Does he ever wish some of his bandmates from that classic 1982, Lexicon Of Love line-up had been there alongside him? “I speak to [drummer] David Palmer every now and again, he plays with Rod Stewart,” he says. “But no, not really. I don’t know. No. Maybe. Maybe I should do a solo record…?”

Maybe. His immediate future, though, is tied up, as it so often is, with that record. Why does Martin think The Lexicon Of Love has endured? “I’m the last person to answer that question, really,” he reflects. “The classic status. I was the one chasing the van as it went off to the cutting plant, going, ‘We need another song on that!’

“I sort of wear two hats because, yes, it’s significant that people still remember something from 40 years ago. It has a life of its own. That makes it a classic.

“But on the other hand, as I say, I’m just the custodian. There were a lot of people involved in that record: Trevor Horn, [engineer] Gary Langan, Anne Dudley, Mark White, Steve Singleton, myself… I’m just the guy in the gold lamé suit at the front of the orchestra. I don’t want to come across as arrogant, because I’m really just a servant. I’m a servant to The Lexicon Of Love’s history.”

Read more: Adam Ant interview

Read more: Glenn Gregory interview