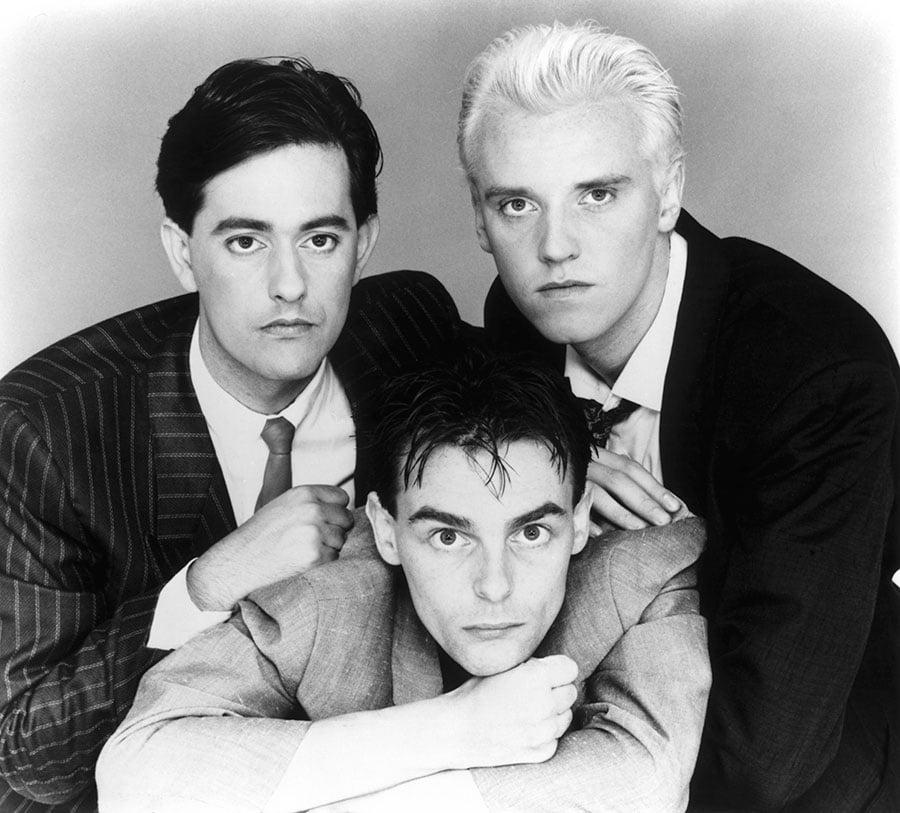

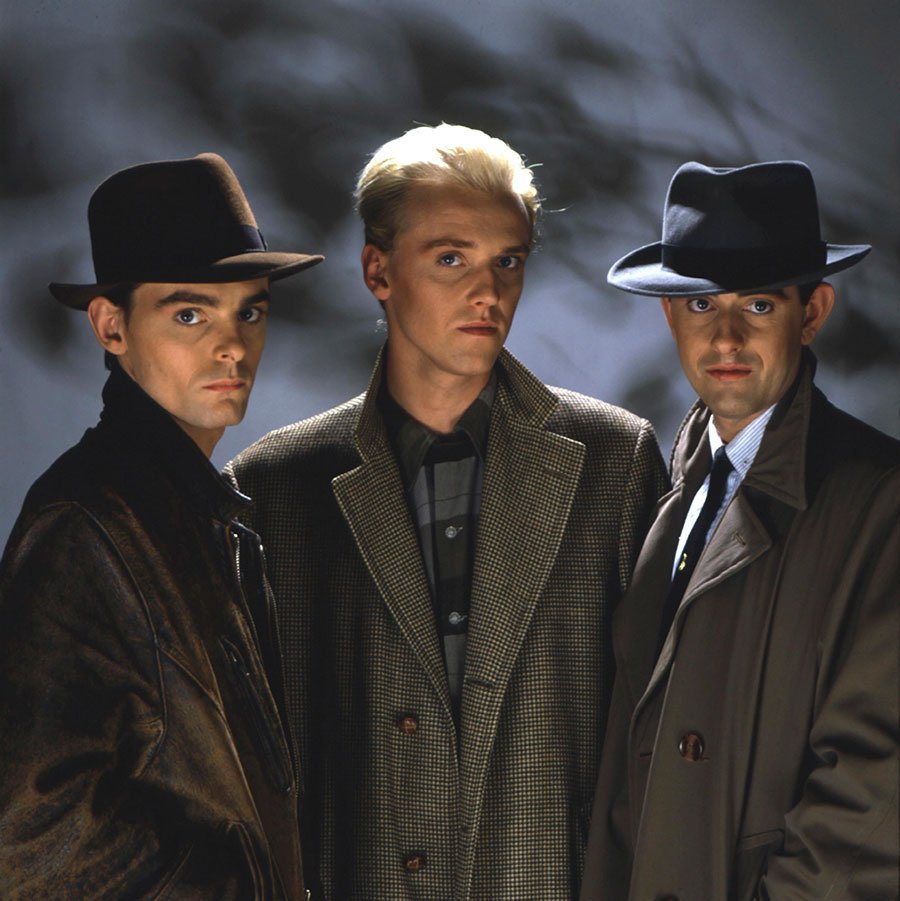

Heaven 17: Glenn Gregory interview

By Andy Jones | March 15, 2022

When the Human League Mk.1 disintegrated, so began a race with big, big points at stake. Who would create the best album? Heaven 17’s singer shares his slant on the infamous split…. By Andy Jones

Band break-ups can be not only extremely messy but also creatively and commercially disastrous, so the fact that both The Human League Mk.2 (with Phil Oakey and Adrian Wright from the original Human League, plus assorted new members) and Heaven 17 (with Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh from Human League Mk.1, joined by Glenn Gregory on vocals) actually produced anything at all in the period following the demise of the original League is, in a way, quite astonishing. The fact that they each promptly produced the best albums of their careers, the year and arguably the decade – and at the same time, and in the same studio – is as near as dammit the most miraculous pop fact in music history.

One man who witnessed it all, and also had a unique connection to both parties, was Glenn Gregory. The ‘new boy’ in Heaven 17 was not only one of the original movers and shakers in the original Sheffield scene of the late 70s but had also been, at one point, a contender to become the League’s lead singer.

1981 was when the Sheffield steel blades were forged and the battle lines drawn between the new League and H17, and the height of the fighting eventually resulted in the mighty Dare and Penthouse And Pavement albums. Never, perhaps, has animosity between two rival bands proved so fruitful. But, as Glenn reveals to Classic Pop, this most prosperous of phases was the culmination of years of Sheffield creativity and a straightforward South Yorkshire-style solution to that very awkward studio situation…

Take us back to those early days in Sheffield when you first got to know the various members of The Human League.

I met Martyn when I was 15 and he was around 17, at an arts workshop called Meatwhistle, a project to bring kids from all over Sheffield together. Ian Craig Marsh was there, Paul Bower, lots of people – it was great fun, a lot of freedom, like-minded kids, theatre projects and loads of different bands.

I was in one band with Ian called Musical Vomit. Paul Bower introduced Martyn to us and we got on really well; he was quite a character and we liked the same music – glam rock, Alice Cooper, New York Dolls, Bowie, Bolan. He quickly became involved. We were definitely punk, vomiting on stage, and the songs were about necrophilia or whatever – it was pretty out there! In Poly Styrene’s [of X-Ray Spex] book she said she saw Musical Vomit and that they were ‘punk before punk’. We dressed kind of like… well, imagine a kind of cheap South Yorkshire New York Dolls [laughs].

What happened after the Musical Vomit experiment?

We got a band together called VDK & The Studs, where I was the singer, and we played one gig at the Psalter Lane Art College supporting The Drones. We were two members of Cabaret Voltaire, Martyn Ware, Ian Marsh, me, and Paul Bower. There were synthesizers, guitars and chaos. For years there was this rumour that someone had recorded it. A couple of years back this guy came up to me and said “Will you sign these?” He’d got some photographs of me from a fanzine we did called Gunrubber, but he also had a reel-to-reel with ‘The Studs’ written on it. I said “You’re not telling me it’s that gig?’ So I now have an Mp3 of it; really badly recorded and absolute noise. It’s barely listenable but it’s priceless, I can’t believe it exists! When Martyn heard it he was like “Where the f*** did you get that from? It’s just like witchcraft!’”

But The Studs only did one gig…

Yes, around that point I was working at the Crucible Theatre as a stagehand and getting bored of Sheffield – a weird place, great fun and it was helpful for us as it made us do things, but I’d decided I wanted to be a photographer and move to London. So after that [Studs] gig, the following Monday, I was getting my stuff out of what we called The Workshop, our little studio, to move to London. Martyn and Ian had been working on some tracks with Adi Newton for The Future which was just pre-Human League. I was going to be the singer so [on that Monday] Ian was saying to Martyn, “Who are we going to get to sing now?” Martyn said, “Well, I don’t know if he can sing, but there’s a kid at my school called Phil and he has a fantastic haircut – he looks brilliant!” They then gave Phil [Oakey] the demo for Being Boiled and said “We’re forming a band, here’s one of the tracks, can you go away and write a melody and some lyrics?” And of course he came back and they loved it, so that’s how I didn’t become a member of The Human League!

So you went to London while they recorded the albums Reproduction and Travelogue…

Yes, I was away for two and a half years, but I saw them all the time. They always stayed at my flat in Ladbroke Grove, so we were all still friends. I was working as a photographer for NME, Sounds and Melody Maker; in fact I even did a cover shoot for Sounds of The League before they split. At that point I went back up to Sheffield to take shots of Joe Jackson at the City Hall and phoned Martyn and asked if he wanted to meet for a drink, and by sheer coincidence it was the day that they’d thrown him out of his own band! They’d had a meeting and later it was found that it was all manipulated by the record company and [League manager] Bob Last. He wanted to get two bands out of one – that’s kind of ‘the history’ now. But Martyn was furious and said “Ian and I are going to form another band, would you be the singer?” So I moved back the following Monday, knocked on my mum and dad’s door and said ‘Hey, I’m back!’”

It must have been a weird situation to be involved in…

Yeah, so The Human League split, it was acrimonious and there was a lot of bad feeling between Martyn and Phil – they were really close friends from school, so it went deep. It was amazing, though, as The Human League had a tour booked and they split just before, but a week later Phil got Susanne and Joanne in and they did the tour! In fact we went to their gig in Nottingham – me, Ian, Martyn and Paul – and I thought it was amazing! I mean, I loved The Human League anyway, but it was fantastic.

Read more: Heaven 17 albums – the complete guide

Read more: Top 40 Depeche Mode songs

The story of how both bands recorded their debut albums in the same studio at the same time has gone down in music history.

The one asset they [Human League Mk.1] had was that they rented a floor in a massive six-storey building. It was disgusting: a derelict building in a row of derelict buildings. It used to be a vets, so there were operating tables and weird shit everywhere. But neither of the bands were willing to give it up, so when it came to writing the two new albums, being pragmatic Northerners, we just split it up and did it in shifts. We did the night shift from 10pm to 10am and then we’d lock our tapes away and Phil, the girls and Adrian or whoever would come in to do the album Dare. They wrote that in that building and we did Penthouse And Pavement. If you’d seen the building, you’d not believe it could be done.

How did it feel stuck in the middle of all that animosity? Did you act as the peacemaker?

No, there was no ‘peace’ to be had. Really, I’m not joking… that split was not friendly. It was properly upsetting, and Martyn felt he’d been dealt a bad hand, so he was trying to prove that everyone had made a mistake. It’s all water under the bridge now, but at the time there was no pally “Let’s go for a pint and talk about it”. Those two friends had split like oil and water, and separated off to different sides of the bowl.

During the recording sessions, did either band ever get to hear what the others were working on?

The only time was when we might hear some snippets of singing, since we both used the same reel-to-reel as a tape echo – I heard bits of Boys And Girls. Occasionally we would make jokes – like on the information strips that are stuck on the mixing desk, we would write ‘Barry White Orchestra’ or something like that, but there wasn’t really any communication. And the weirdest bit about it was that Phil was actually living on the floor above the studio, so his bedroom was right above us. So while we were working at night, doing (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang or whatever, Phil would be up there! It was quite an amazing situation, kind of like living in a surreal 70s sitcom: My Ex-Band Next Door!

How soon did you realise that you were doing something special with Penthouse And Pavement?

Pretty early on. The energy was immense because both parties were desperate to be successful and, quite frankly, to prove that they were better than the other. The first track we did was Jimmy Webb’s Wichita Lineman which ended up on a B.E.F album [Music Of Quality And Distinction (Volume One)]. It sounded great. The Human League didn’t use any acoustic instruments, it was all treated sounds and synthesizers, but we were free to do what we wanted, so on Wichita Lineman we had acoustic guitar – I played sax on there and also on Fascist Groove Thang, which we did next.

When the album was complete, were you still convinced?

Yes, we really loved it and it wasn’t really like anything else, which can be both good and bad. When Fascist Groove Thang came out as a single, we’d stayed up all night and gone to Penny’s nightclub until 3am and then back to Ian Marsh’s house and we were all watching Kenny Everett on video. At 5am we got the 93 bus and waited for the newsagents to open and bought all the papers, hoping that someone might review Fascist Groove Thang. It turned out to be Record of the Week in Sounds, NME and Record Mirror and we were like “They’ve got it!” So we knew we had something reasonably special because people had got what we wanted them to get: the political and the musical nature.

Read more: Best Human League songs

Read more: The Human League – Album By Album

Was the overt politics intentional?

It was part of all of our upbringing. My dad was a shop steward at the steelworks and very political, similarly with Martyn and Ian. It’s kind of a Yorkshire thing to be left-wing, like the Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire! Politics was something we all liked to talk about and a great thing to bring into our music. In a way it allowed us to be slightly smart-arse, the fact that we were getting these messages into our work without shouting [too much]. Songs like Play To Win, Crushed By The Wheels Of Industry and Let’s All Make A Bomb – a lot of people thought they were just pop songs but there’s a political and social intercourse through all of our lyric writing.

As good as Penthouse And Pavement is, was there much jealousy about how Dare took off?

I don’t think so. For me it was different as I wasn’t a member of The League and I was friends with everyone, and also Dare is a brilliant album, you can’t knock it, it’s fantastic. Penthouse And Pavement was a very cool album and it got talked about a lot and it stayed in the charts for over a year. It was a real slow burner, not as immediately ‘pop successful’ as Dare. Dare was a zeitgeist thing: the right place, right time, right producer, right girls, right boys, everything. So I don’t think there was any jealousy but it did add fuel to the fire of us wanting to be more successful.

Read more: Top Eurythmics songs