Making XTC: English Settlement

By Felix Rowe | March 22, 2022

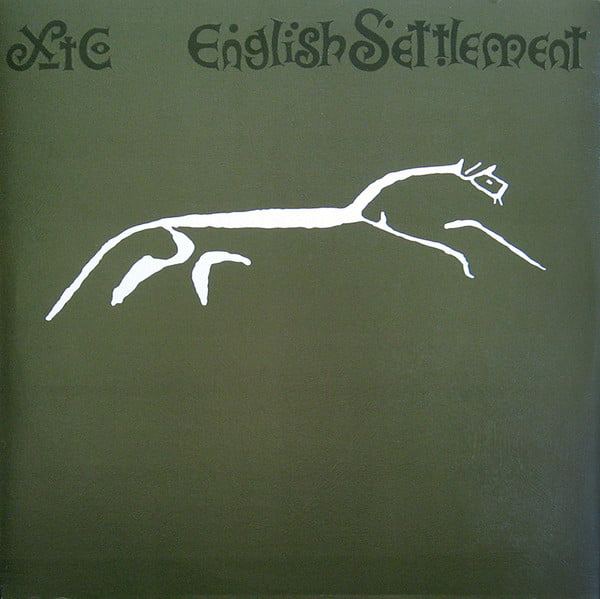

The fifth album by XTC, English Settlement, was a landmark as bold as the beast on its cover; a double-album that saw the group expand their sound, turn their backs on the live arena and venture into scenic new territory… By Felix Rowe

Deep in the heart of the Oxfordshire countryside, a colossal white horse has been carved into the chalk hills – the Uffington Horse is one of several across England, steeped in folklore and seemingly as ancient as the hills themselves. Emblematic of our need to set down roots and stake a claim on the landscape, it also serves as a reminder that the world is far bigger than self.

It’s no coincidence that this deeply loaded symbol was reappropriated by the group XTC on their landmark double album, English Settlement, recorded in the neighbouring countryside. Eight miles from their hometown, Swindon, it’s a fitting image to represent XTC’s move towards a more bucolic outlook, at a time when the band were actively reassessing their own sense of identity.

On English Settlement, the band’s trademark muscular, angular live sound was, not toned down, but expanded into a cinematic widescreen. XTC weren’t the only post-punks to take such a route. Whether by accident or design, they were just one of several UK groups to embrace a more pastoral language at the turn of the 80s.

While the emerging synth-poppers were creating the future, The Stranglers were rolling out the harpsichord on Golden Brown and Dexys were adopting folk leanings on Too-Rye-Ay.

But for all that, English Settlement is far removed from a folk record. Certainly there’s more organic instrumentation, notably acoustic guitar and 12-string Rickenbacker adding more jangle; but it’s not all fiddles, hurdy-gurdy, and dancing around the Maypole.

It’s very much a modern rock record, utilising the latest studio trickery at the band’s disposal. A Prophet 5 synthesizer and a drum machine were brought in specifically for its recording. The point is, it marked a sonic expansion that set them on a path of increasing breadth and melodicism.

Far from retreating inwards, this exploration of roots saw them gazing outwards. The album is positively laced with world rhythms, from the skittish It’s Nearly Africa to the vibrant ska of Down In The Cockpit. World instruments including the angklung (a Sudanese percussion instrument), and the timbale drum added new textures into the mix.

English Settlement is largely a groove-based album, built on layers of riffs and rhythms weaving in and out. Characteristic of XTC’s earlier work, it often feels like they’re propelling along on a speeding train, gathering ever more momentum, seconds from disaster, with no choice but to thunder on frantically. It makes for a thrilling listen.

It was a pivotal record for XTC in many ways – in the words of guitarist Dave Gregory, “a watershed” moment, and the start of what frontman Andy Partridge calls their Sgt Pepper period. It’s a reference not simply to greater experimentation but, crucially, their shift from an abrasive live act to an entity that existed purely in the studio.

Years of touring had taken their toll on Partridge’s health to the point where it became physically impossible to continue. What’s more, by 1981, he was struggling with withdrawal from the Valium he had been prescribed since childhood. Racked with stage-fright and burnt out from the rigours of touring, Partridge consciously adopted more complex arrangements that the band wouldn’t be able to recreate live, in the hope of easing pressures to hit the road.

When the inevitable tour cycle for English Settlement began, shows in Europe and US had to be cancelled after Partridge was immobilised on stage. Henceforth, all touring ceased, save the occasional TV and radio appearance.

Sadly, the scant live footage that does exist from this era (including a raucous set on German TV) confirms both what a vital live force they really were, and how well these tracks worked on stage.

Befitting the pastoral theme, the album was recorded at the Manor House, a legendary (and now defunct) studio, owned by Richard Branson as a residential studio for Virgin Records artists, although other labels used it too. It’s where Tubular Bells was recorded, among countless other classic albums, from Paul Weller’s Stanley Road to Radiohead’s The Bends.

To help capture their vision on tape, the band turned to Hugh Padgham, who had engineered their earlier work produced by Steve Lillywhite. Padgham (the man responsible for pioneering the classic Phil Collins gated snare sound that characterised the 80s) was chosen for his ability to craft interesting sonic textures, without interfering creatively.

The core tracking was mainly captured live in the room in the traditional way, with overdubs added on top. The result was a growing sophistication and maturity without their sharp edges completely sanded off.

Read more: Top pop songs of 1981

Read more: Top pop songs of 1982

According to Partridge, in a typically sardonic interview response, the extent of the band’s rock and roll exploits at the Manor included playing conkers. Padgham tells a slightly different story of the band staying up late, playing Hendrix and Led Zeppelin covers with Partridge making up his own lyrics, before hitching up his underpants to do impressions of sumo wrestlers.

When it comes to XTC, Partridge tends to hog the headlines, which is not altogether surprising. He’s a subeditor’s dream, bursting with pull quotes delivered with a cheeky grin and an acid tongue. His growling, snarling and stuttering vocals – paired with facial ticks and sideways glances – are a defining feature of the group.

Though bassist Colin Moulding contributed less frequently as a songwriter and occasional lead vocalist, he was responsible for some of XTC’s biggest chart successes. On English Settlement he offers four tracks, including the atmospheric opener Runaways and single Ball And Chain.

He’s not a bad singer too, broadly similar in timbre to Partridge, though more soulful and less abrasive. And what an underrated bassist; comparisons with McCartney’s melodic low-end aren’t entirely fanciful.

Dave Gregory’s guitar work shines and shimmers throughout this record. But the input of drummer Terry Chambers as a key driver deserves wider recognition. Chambers is no mere metronome. He rarely holds a pulse; rather his rhythms are frequently shifting and shuffling. He’s an intelligent but intuitive drummer, playing parts rather than beats, deviating away from the core pulse.

He often approaches it like one continuous drum fill – not trying to steal the thunder in a flashy, Spinal Tap way, but pushing and pulling the track sideways into uncharted territory. English Settlement was another milestone: Chambers’ last full album with XTC, before he emigrated to Australia.

English Settlement brought XTC a Top 5 UK album and they were primed to hit big stateside too. Yet unlike some of the other classic albums of 1982, English Settlement didn’t quite gather the critical mass necessary for full-scale commercial success.

While often threatening to do so, XTC never managed to shake off the cult status tag. Each new record brought critical acclaim without the sales to match and they remain in relative obscurity. Some commentators might call them masters of self-sabotage.

Matters of touring aside, and whether or not warranted, Partridge gained a reputation for being steadfastly stubborn and awkward (bolstered by his tumultuous experience working with Todd Rundgren on 1986’s Skylarking).

Even in their poppier moments, there’s invariably a catch; an abrasive element or unwillingness to play it totally straight (neatly demonstrated in Senses Working Overtime, its colossal hook-laden chorus juxtaposed with the rhythmic oddities of the verses).

But like XTC’s wider canon, English Settlement has lived on in the myriad groups it inspired. They have been called the Godfathers Of Britpop. Blur, who would themselves explore a sense of Englishness, were huge fans and Partridge was their first choice to produce their second album. And might the title of Blur’s debut Leisure have been a reference to its namesake track on English Settlement? But their reach stretches further than that.

If success was measured not in record sales but namechecks from other artists, then XTC would be supreme rulers of the universe. XTC’s influence has spread far and wide, permeating pop culture across the globe. Fans directly influenced by the group include everyone from Red Hot Chili Peppers to Tim Burton’s favourite film score composer, Danny Elfman, and Japanese composer Keiichi Suzuki.

In a special profile of English Settlement, in-demand producer Warren Huart calls XTC: “One of the most influential bands of all time”, based on his experience of working with some of world’s biggest groups.

Just like the white horse that adorns its cover, English Settlement is a landmark, both timeless and of its time; an icon that deserves to be revered long after its originators have moved on to pastures new. In truth, the record is not quite as bucolic or ‘English’ as the title suggests; but it set XTC on a path to explore these notions more fully on later albums.

But, a final thought: what did XTC’s US label exec make of the iconic cover? “It looks like a duck!” He then offered to get his guys in to draw them a proper one.

Read more: Making The Hounds Of Love

Read more: Kate Bush albums – the complete guide

XTC: English Settlement – the songs

Runaways

The album opens with a percussive, propulsive rhythm of acoustic and jangly guitars, supported by hi-hats fading up to a chant-like vocal of “Runaways”, before a booming tom drum pulse crashes in. Colin Moulding handles lead vocal duties, while backing vocals respond with a “don’t cry” refrain, processed and pitched up to create an eerie, unsettling sound. It’s a wonderfully atmospheric, expansive yet understated opening, perfectly setting the scene for the varied landscape that follows.

Ball and Chain

This second Moulding composition sees XTC in more familiar new wave territory, with ching-ching guitars recalling The Clash’s Mick Jones and thunderous drums in a shuffling glam stomp. Lyrically, it’s a Thatcher-baiting rallying cry against the demolition Moulding was witnessing around the mean streets of Swindon.

Senses Working Overtime

The closest the band came to a bonafide hit, and a conscious attempt to do so, while retaining their eccentricities. Beginning with an acoustic guitar riff and primal rhythm on a single drum, the verses are very strange rhythmically, with bass and drum accents seemingly falling in the wrong place, making the song trip up over itself – Partridge’s strangulated vocals that recall Kevin Rowland. The chorus is the antithesis of the verses, a big catchy hook that lodges itself in your brain and refuses to leave.

Jason And The Argonauts

Similar to Runaways, it opens with shimmering rhythmic guitars that are constantly revolving and shifting through to the glistening outro, with an almost canonical feel. It has a hypnotic quality as the parts interweave. Lyrically, it takes the travels of Jason and the Argonauts as a metaphor to reflect Partridge’s distaste and unease at touring, as well as the more unsavoury aspects of humankind encountered on his travels.

No Thugs In Our House

The mood is swiftly switched up with a simple spit-and-sawdust rock and roll arrangement. Percussive acoustic strumming in the verse and primal screaming lead into a big thumping chorus, with accents on the four-to-the-floor snare hitting on every beat; this is closer to their early punky, art-rock sound. The mid-section drops the aggression for a more melodic (and almost calypso) sound, before going back into the aggression with a razor-sharp guitar riff from Gregory.

Yacht Dance

Not a slice of soft-core yacht rock as the title might suggest, but actually a skittish, jittering track built on frantic rhythms that skip and dance over each other lightly. The tempo is dropped with some lovely acoustic guitar picking. It wouldn’t sound out of place on Vampire Weekend’s first record, released some 25 or so years later.

All of a Sudden (It’s Too Late)

The closest you’ll get to a ballad, but still propelled along by the drums. It finds Partridge at his most melodic and romantic. Its slower pace is a welcome reprieve to the sensory overload of some the more chaotic moments on the album. Lyrically mournful, it laments the passing of time and how you need to grasp opportunities when they arise.

Melt the Guns

Another jerky and jittery track with world rhythms, it opens with a tribal funk feel and lots of primal yelping. Lyrically, it’s a more overtly political track, promoting gun control, in particular aiming its vitriol very specifically at the US and ‘Justice League of America’. Repetitive distorted and looped vocals in the mid section, and again the stuttery chants in the outro, hammer the point home to unsettling effect.

Leisure

This skulking, stomping rock number is announced with a single strangulated Partridge a capella vocal, giving way to a walking bassline with a menacing quality. Lyrically, it’s another political comment, taking a barbed view on the misconceptions surrounding unemployment and the real causes behind it: “If you think I’m clowning, I assure you that I’m drowning here… searching for the jobs that don’t exist.” A screeching saxophone solo echoes the unsettled nature of the theme.

It’s Nearly Africa

It’s jittery and skittish, with more tribal rhythms, beating Paul Simon’s Graceland to it by four years. Cue lots of chanting and howling, and interesting woodwind instruments that could well be synths. The song had been kicking around since 1975 and according to Partridge it was about getting back to roots and away from technology: “It was a little celebration of all things primitive, of how we should slow down and appreciate being basically animals, in the good sense of the word.”

Knuckle Down

A single that should’ve been – it’s a bouncy and Beatles-y track, like a McCartney off-cut from Sgt Pepper’s. Extremely melodic, it’s carried along on a shuffling groove and infectious vocal hook. Musically, it’s one of the most straight-up and simple arrangements, with less overdubs and more space for the melody to breathe. Lyrically, it calls on people to see through the superficial nature of race to live in harmony, and Partridge delivers the sentiment without sounding mawkish.

Fly on the Wall

A faster new wave number, incessantly catchy, with a propelling bass part, driving drums and synths. Another Moulding-penned gem, his vocal delivery, paired with the tremolo guitars, invokes a psychedelic 60s vibe, pre-empting their later Dukes of Stratosphear alter-egos. The nagging synth part brings it back to the present. It’s refreshingly different and should’ve been a single. While, in many ways, it’s the most standard garage band song on offer, the production treatment takes it into fresh territory. A big thumbs up.

Down in the Cockpit

The album sees another about-turn, as the band reinvent themselves as a ska group, taking cues from The Specials’ earlier work. Jittering rhythms and staccato muted guitar riffs make this the perfect track for skanking on the dancefloor. But, as ever with XTC, all is not quite plain sailing and the catchy upbeat feel belies the message of the song, a pro-feminist manifesto decrying downtrodden women at the hands of men.

English Roundabout

Another very skittish track, very rhythmic with that sense of African rhythms, showcasing Chambers’ intuitive drumming and some nice guitar from Gregory. Apparently, it’s not specifically about a certain roundabout in Swindon as some have suggested, but rather a broader comment on escaping the rat race.

Snowman

This is built on intricate revolving guitar refrains and grooving drums with rhythmic, jittery vocals and occasional vocal yelps. A more melodic section adds a counterpoint on the “Why, oh why?” refrain. It has an improvisational feel and, like much of English Settlement, it’s more like a groove-based jam than a song. Again, the drums don’t play a beat; instead thunderous booms are contrasted against rhythmic accents. Fading out to end, it shares some similarities with opener Runaways, two bookends topping and tailing the complete song cycle.

Read more: Talk Talk – album by album