Madonna was one of the first to create a visual identity as significant to her legacy as her music – with over 70 music videos to her name, the Material Girl has used her videography as a platform to express herself like no other…

It’s hard to imagine, given the sheer magnitude of Madonna’s iconic videography, that when she started out she was regarded as a faceless dance act with no videos and no photographs on her record sleeves.

Her early anonymity could have understandably led anyone listening to ask – to quote one of her most famous hits – “who’s that girl?” Soon, though, that question would be rendered null and void, as within a matter of months that girl was MTV’s First Lady, a natural star who was seemingly born to be in front of the camera.

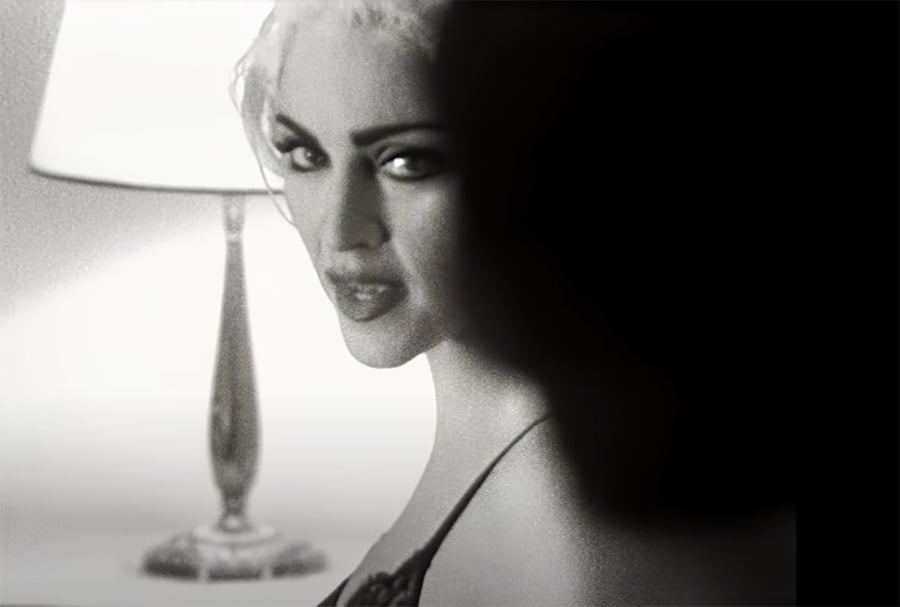

A simple clip, shot in grainy black and white, of Madonna lowering her sunglasses at the beginning of the Lucky Star video heralded the arrival of the woman who would come to define the video age. As Burning Up and Lucky Star swiftly became MTV mainstays, Madonna’s in-your-face attitude and streetstyle already saw her rivalling Prince and Michael Jackson for airtime.

By Borderline, she was a walking billboard for her graffiti artist friend Keith Haring’s fashions, the achingly hip downtown diva who embodied the essence of New York cool. Directed by Mary Lambert, Borderline’s heavy rotation on MTV fuelled the song’s success, delaying the release of Madonna’s second album.

During the interim, Madonna and Lambert collaborated on a pair of videos that would cement her ascension into superstardom – the girl-on-a-gondola romp of Like A Virgin, which debuted her infamous “wanton bride” persona, and the wry pastiche of Marilyn Monroe’s Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend in Material Girl.

By the time Madonna returned in 1986 with a sleeker new look, she had made the transition into films with Desperately Seeking Susan, an experience which altered her view on video making. As her music was becoming more issue-led, she began using her videos as narratives to elevate the messages contained within her music.

In Papa Don’t Preach, the first of her “mini-movies”, she was compelling as the vulnerable pregnant teenager. It was a similar story with True Blue’s other videos, the sexually-charged peepshow performer of Open Your Heart and the Latin love story of La Isla Bonita.

Following a further detour into film with Who’s That Girl, the media began questioning why a star so dynamic in her videos was unable to replicate that onscreen presence to her film roles.

1989’s Like A Prayer, once again directed by Mary Lambert, was by far her most controversial to date, with a racially motivated murder, stigmata, Madonna kissing a black saint on an altar and dancing in front of a field of burning crosses among the scenes the media picked up on. “Badonna”, as they called her, had gone too far. The video was banned around the world and cost Madonna a huge sponsorship deal with Pepsi.

The video may have hit Madonna financially, but it was very lucrative in what it taught her about the music business and the media. The acreage of free publicity she received from the Like A Prayer debacle instilled in her the controversy-equals-currency ideal – something she implements with great success to this day. Whether intentional or not, Like A Prayer signalled the most interesting, subversive period of Madonna’s career.

Read more: Making Madonna’s Like A Virgin

Read more: Madonna On Film

For the next five years, her videos marked her out as a true maverick, constantly delivering bold, fearless videos designed to provoke reactions, good or bad, and incite discussion on matters important to her. As the medium of the music video had evolved into a major promotional opportunity, a whole new generation of talent was emerging as a host of talented creatives battled to make their marks as videomakers. As the biggest, most daring star in the world, Madonna had her pick of the bunch.

Express Yourself, David Fincher’s futuristic fantasy, examined the place of women in society and cast Madonna in a variety of roles, from the power-crazed businesswoman to the enslaved sex object chained to a bed. Costing a cool $5 million, it was the most expensive video ever made at the time.

She worked again with Fincher for Oh Father, a haunting video in which Madonna relives her childhood and the death of her mother with devastating poignancy, while her close friend, photographer Herb Ritts, provided some light relief with his natural video of a playful Madonna frolicking in the surf of Malibu beach with a bunch of mermen for Cherish.

Shot in black and white, Ritts’ fashion-photo-come-to-life directly influenced the aesthetic David Fincher used for the Vogue video. Just as the song celebrated Hollywood’s golden age and icons of the past, the video did the same, directly referencing vintage films and the photographs of Horst P Horst.

While Vogue had landed Madonna a partial MTV ban and was only played after 9pm due to her wearing a completely sheer shirt without a bra, it was nothing compared to the controversy generated by her next video, Justify My Love, containing S&M, group sex and a lesbian kiss. It all added up to Madonna’s biggest controversy since Like A Prayer.

Citing hypocrisy, sexism and homophobia, Madonna continued to explore those themes in her Erotica video, a 35mm-shot kinky kaleidoscope of footage filmed by Fabien Baron as she shot her notorious Sex book. In the midst of a severe media backlash due to the book, the Erotica era saw Madonna at her most fearless.

She explored the dark decadence of disco in the Warholian sexuality of Deeper And Deeper, Fever saw her cast by Stéphane Sednaoui as a “provocative Saint” immortalised in silver body paint, the slick Far Eastern futurism of Mark Romanek’s Rain remains one of her most beautiful videos, while Bad Girl, David Fincher’s cinematic masterpiece, is her most underrated video.

Read more: Madonna – Ray Of Light

Read more: Making Madonna’s Like A Prayer

Starring Madonna as an alcoholic businesswoman with an appetite for casual sex, her antics are watched over by a guardian angel (played by Christopher Walken) who delivers a kiss of death before she is finally strangled by a one-night stand.

1994’s Bedtime Stories found a performer that was mellower but just as captivating, delivering a set of equally boundary-pushing clips.

Melodie McDaniel’s black and white video for Secret cast Madonna as a Harlem nightclub singer; the lush romanticism of Michael Haussman’s Take A Bow pictured a Forties-set love story between the singer and a matador; Mark Romanek took a surrealistic, painterly approach to Bedtime Story, a tech-assisted masterpiece which transported Madonna into various surreal scenarios with astonishing results; and Human Nature, her first collaboration with Jean-Baptiste Mondino since Justify My Love, was an S&M-inspired kiss-off to Madonna’s detractors. She spends the clip in a latex catsuit being forced into a box before emerging free at the end to deliver a defiant “Absolutely no regrets” straight to camera as if speaking directly to her critics.

Following a period in which she achieved success with Evita and became a mother, a rebranded Madonna emerged in 1998 with Ray Of Light, the confrontational provocateur having been replaced by a serene, spiritually-sound Madonna. Her stunning comeback video Frozen saw her team up with Chris Cunningham for a stark, gothic piece in which, almost unrecognisable and dressed entirely in black, she mutates into a rabid dog and a pack of ravens.

In complete contrast, Jonas Åkerlund’s visionary genius was in peak form for Ray Of Light which featured a golden-hued Madonna dressed in a simple indigo denim jacket performing the song as the transcendental rat race raged around her, while Walter Stern’s Drowned World perfectly captured the paranoia and loneliness of celebrity.

It also caused controversy due to scenes of Madonna in a car being chased by paparazzi being eerily similar to those surrounding Princess Diana’s death. The Power Of Goodbye and Nothing Really Matters, a Memoirs Of A Geisha-inspired clip completed Ray Of Light’s run of faultless visuals.

After the emotional intensity of Ray Of Light, Madonna released two comedic videos. Brett Ratner’s Beautiful Stranger was a hilarious face-off between Madonna and Mike Myers’ Austin Powers character, while Music, a send-up of hip-hop’s “ghetto fabulous” culture, saw her bedecked in a fur coat, sipping champagne and visiting strip clubs in a limo driven by Sacha Baron Cohen’s character Ali G.

After the simple Americana of the beautiful Don’t Tell Me video, Madonna released a spate of videos which seemed predominantly violence-led. Guy Ritchie’s What It Feels Like For A Girl featured Madonna staging robberies, joyriding, blowing up a petrol station, mowing down pedestrians and deliberately crashing her car into a lamppost.

This streak continued with Die Another Day, directed by Swedish outfit Traktor. Costing $6 million, the video saw Madonna under interrogation in a prison, with depictions of violent beatings and fight scenes which referenced the 2002 James Bond film from which the song came.

With the war in Iraq playing heavily on her mind, Madonna chose to release an anti-war video to launch her American Life album in 2003. However, the graphic depictions of the horrors of war and an easily-misunderstood message forced her to withdraw the video prior to release.

The move derailed her entire album campaign; instead of being led by one of her greatest artistic statements, it was led by one of her worst – a hastily put-together video of Madonna singing in front of a backdrop of changing flags.

Read more: Kylie Minogue on film and TV

Read more: Top 20 girlband singles of the 80s

Her second video from the album, Hollywood, a satire of the beauty industry, fared much better, featuring the singer in a variety of glamorous set-ups inspired by fashion photographer Guy Bourdain. So accurate were Madonna’s reinterpretations, in fact, that she was sued by his estate for copyright infringement.

Having learnt her lesson, Madonna donned her leotard and kept the inspiration on the right side of homage for Hung Up, which presented a modern take on disco, fusing nods to the Saturday Night Fever and Perfect movies and Olivia Newton-John’s Physical with breakdancing and parkour. The Johan Renck video stood up among Madonna’s best and helped put her back at the top of the charts around the world.

As the music industry has changed in recent years and videos have become less prominent, the glory days of four or five videos per album have long gone, with the now-accepted norm being a great lead video followed by two or three will-this-do? efforts, as seen with Confessions On A Dancefloor.

2008’s Hard Candy fared even worse. While the Justin Timberlake collaboration 4 Minutes received the big budget treatment, it bore none of the brilliance of the past, while the album’s other offerings aren’t worthy of being mentioned in the same breath as her classics.

In recent years great Madonna videos have been slim pickings with her best videos featured as installations in her live shows. MDNA’s Give Me All Your Luvin’ was a fun celebration of her Super Bowl performance, while Girl Gone Wild (the first music video by fashion photographers Mert and Marcus) was a stylised homage to her early Nineties Erotica era.

The apocalyptic, poignant Ghosttown was an overlooked gem while Bitch I’m Madonna was an unexpected delight and by far Madonna’s best video since Hung Up. Vibrant, unapologetically fun and packed with attitude, it captured the very essence of Madonna that we fell in love with nearly 40 years ago.

Read more: The alternative David Bowie top 20

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.