Remembering Manchester’s Haçienda nightclub

By Mark Lindores | April 8, 2022

Manchester was primed for an era-defining mecca of music by the time the Haçienda nightclub opened in 1982. For the next 15 years its pills-and-thrills fuelled hedonism spawned a legacy that still thrives to this day…

Manchester was primed for an era-defining mecca of music by the time the Haçienda nightclub opened in 1982. For the next 15 years its pills-and-thrills fuelled hedonism spawned a legacy that still thrives to this day…

The brainchild of music impresario and New Order manager Rob Gretton during one of New Order’s first tours in 1981, the Haçienda nightclub was inspired by vibrant New York nightspots such as Danceteria, Funhouse, the Roxy and Paradise Garage – clubs which had proved to be a shot in the arm to New York’s post-Studio 54 nocturnal wasteland, a similar state in which Manchester had found itself in at the time.

While visiting those clubs, Gretton, along with Tony Wilson and New Order, experienced an epiphany that would transform Manchester in much the same way as it had Manhattan.

Far from being the dubious dens of cocktails and hook-ups that passed as nightclubs in the UK, these vast, multi-level emporiums throbbed with the eclectic sounds of hip-hop, salsa, rock and electro, all mixed seamlessly together to create an unforgettable soundtrack to high times, the likes of which they had never experienced before.

Feeling inspired and enthused upon their return to Manchester, they ploughed Factory Records’ profits from Joy Division into a disused yacht showroom and began the formation of the first club of its kind in Britain.

Although advised that building a recording studio would be a more feasible plan of expansion of the Factory brand, they could not be dissuaded, feeling that a club was both a sound investment and a place where the Factory crowd could hang out. As there was nowhere in Manchester playing the music they liked, they felt in a position to create their own.

Assembling a team to help make their vision a reality, Gretton and Wilson enlisted Mike Pickering to book acts and DJs, while Factory sleeve artist Peter Saville recommended Ben Kelly to design the interior of the club.

“It was a dream opportunity,” recalls Ben, who used the minimalistic aesthetic of Factory and New Order artwork as his basis. “Simplicity was the key to what it would look like. I had this vast space and these wacky clients, and no-one really had any idea of what it was they wanted. It turned into this kind of monster orgy of self-expression.

“Because there were columns throughout the dancefloor which could be perceived as hazardous, it just occurred to me to mark them with stripes in the way that they would have been in a real-life factory, an industrial environment where hazards are marked with coded colours.”

Capturing the essence of the clubs that inspired it, the Haçienda incorporated a café/restaurant, three bars and gallery space as well as the main stage/dancefloor area, firmly establishing itself as a creative hub for like-minded Mancs – although the mainstream crowd were hesitant in acknowledging its appeal.

Read more: The story of Spike Island

Read more: Top 20 80s house hits

“It was something different and the old school was opposed to any change, even though the old school existed in dingy clubs which had carpets that stuck to your feet,” recalls Mike Pickering. “We were so ahead of our time – people were like, ‘What is this?’ There was nothing in the country like it.”

Despite being open every night, the club was not the runaway success hindsight has afforded it. The first few years were very tough financially and it was little more than a stop-off for up-and-coming bands such as Culture Club, Simple Minds, Thompson Twins, OMD (who had recently released Electricity on Factory before signing with Virgin) and Eurythmics.

A ‘successful’ show at the Haçienda meant a crowd of about 600. “We had a lot of names playing at the club before they made it big, but very few came back once they’d made it!” Mike laughs.

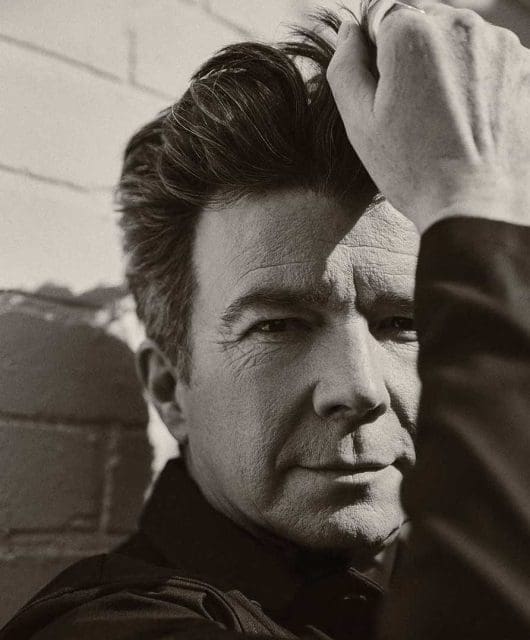

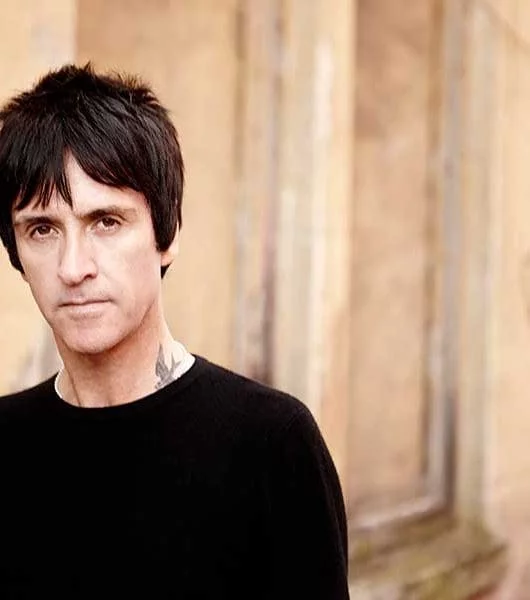

In the first two years of the club, only gigs by local heroes New Order and The Smiths managed to sell out the 2,000-capacity venue. The show by Morrissey and his cohorts – which took place immediately after the band had performed This Charming Man on Top Of The Pops – is still regarded today as one of the greatest sets The Smiths ever played.

Another Haçienda performance that has gone down in music history is that by Madonna, who performed there for an outside broadcast for The Tube. A relative unknown at the time, her miming and gyrating along to Holiday for her first UK TV performance underwhelmed the crowd, who threw food and drinks at her. Rob Gretton’s £50 offer for her to perform another set later that night at the club was impolitely declined, and she made a hasty exit.

Frustrated that the club seemed to be deviating from its initial Danceteria and Paradise Garage direction, a shake-up of the club’s events and door policy began a huge turnaround in the Haçienda’s fortunes. The introduction of Mike Pickering’s Nude club night on Fridays was instrumental in defining what is now regarded as the pinnacle of the club.

“I started Nude in October 1984,” Mike says. “It was the first of its type, because what I wanted was for my mates to get in. Everywhere in clubland in Britain at that time, if you were a complete thug and wore a shirt and tie then you got in and could cause trouble. But if you wore a nice Armani top and some nice trainers, then you couldn’t get in – and that’s what we all were. That’s what New Order were, what Rob and I were, so we shook it up a bit.

“We made it free to people who were on the dole, and it was brilliant – it was the first place to accept those kinds of people. From that point we always got about 1,200 people in on a Friday night. Saturdays were always busy, but that was a trendier crowd.”

Read more: The Bristol sound

Read more: Making The Stone Roses’ debut album

This shift away from flamboyance and elitism marked a big turning point in the types of people that went clubbing. They may not have been dressed in outlandish outfits and make-up, but the way they looked was just as important to them… just expressed differently.

Rather than trying to outdo one another, the message was of unity and giving people a feeling of belonging. A strong tribal aspect was added by the adoption of such labels as Joe Bloggs, Naf Naf and Gio-Goi, all purchased from Manchester’s fashion emporium, Affleck’s Palace.

“This was really when the idea of fashion branding came to the fore,” says DJ/writer Princess Julia. “Designer labels, tags, expensive sportswear became quite a uniform style for some. It may look like everyone was dressed down, but actually a lot of the fashion was very precise and thought out.”

For many, Nude was the first introduction to the sounds of New York that had inspired the Haçienda nightclub in the first place. The burgeoning dance scene that would explode in the following years was bubbling under, and those that flocked to Nude were often to be found in Eastern Bloc records the following day, frantically trying to track down the records that they had danced to the previous night, often to no avail.

Having built up a rapport with DJs such as Mark Kamins, Derrick May, Arthur Baker and Frankie Knuckles, Mike was importing records directly from New York, Chicago and Detroit that gave his sets an exclusivity not seen since the Northern Soul days.

As well as tip-offs about records, Mike was instrumental in booking the DJs to play sets at the Haçienda for huge fees and first-class treatment, pre-empting the superstar DJ phenomenon.

By 1987, the advent of rave culture and the introduction of ecstasy transformed the club scene beyond recognition, with DJs feted like rock stars and in demand all over the world. Meanwhile, in London, a triumvirate of club nights, Danny Rampling’s Shoom, Paul Oakenfold’s Spectrum and Nicky Holloway’s The Trip, all inspired by a night in Ibiza’s Amnesia club, became the Southern contingent of the Acid House movement.

Although the sounds had reverberated through the Haçienda’s sparse steel interiors for a number of years, 1988-89 saw what was previously underground dance music cross over to the mainstream. Records such as Frankie Knuckles’ Your Love, Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley’s Jack Your Body, Mr Fingers’ Can You Feel It and Guru Josh’s Infinity all became chart hits.

Read more: Making Primal Scream’s Screamadelica

The biggest of all was Black Box’s Ride On Time in 1989, which sold over 1 million copies and was the biggest-selling single of the year. Mike was given the track one Friday night and, recognising it as a future smash, set about releasing it, only to face opposition from Loleatta Holloway, whose track Love Sensation it sampled.

“We had to re-record the vocals to get clearance on it,” says Mike. “So we flew Heather Small out to Italy to record it, and it’s Heather on Ride On Time. It’s her vocal. If you listen there’s certain giveaways, but no-one ever knew! We had to do it really quickly so we could release it, because the original one had the sample on, and we replaced the sample with Heather! It’s probably the biggest-ever Haçienda record. People think it’s a big pop hit now, but it was massive.”

By the beginning of the 90s, Acid House was the subject of a major backlash with TV debate shows and newspapers hysterical about the “dangerous drug culture impacting the nation’s youth”. As so much rave culture was spontaneous and happened at impromptu times and places, it was hard to police. The Haçienda nightclub became the public face of the scene – and it bore the backlash.

Despite the negative effect of dance culture, the Haçienda’s cultural significance was greater than ever due to the explosion of bands that had formed and evolved there.

The success and notoriety of the club, inspired young bands to believe that they could indeed make something of themselves, and The Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, Inspiral Carpets, 808 State, The Charlatans, The Farm, The Mock Turtles, even Candy Flip all went on to achieve chart success and become part of what would be dubbed Madchester.

Read more: Happy Mondays interview

Read more: Making New Order’s Technique

The Haçienda’s fusion of sounds would also prove to be the catalyst for one of the most seminal records of the era. Creation label boss Alan McGee was in the grip of a chemically-enhanced euphoria when he had an “E-piphany” that swirling psychedelic guitars teamed with blissed-out beats would be the perfect direction for his band Primal Scream. The following day he put them in the studio with DJ Andrew Weatherall to work on their Screamadelica album.

Although the Haçienda nightlcub had been responsible for some of Manchester’s greatest highs, culturally and literally, the end was near. Rival gangs of drug dealers fought each other for prevalence, with many innocent bystanders caught in the crossfire.

A series of muggings, robberies and stabbings caused irreparable damage to the club’s reputation and this, together with mounting debts, was responsible for its temporary closure in 1992. It reopened months later and struggled on until 28 June 1997, but the party was over.

“It was over for me when we shut down that first time,” Mike says. “Manchester was in the grips of this tremendous lawlessness, and the police didn’t want to do anything about it. There was millions of pounds spent each weekend on drugs, and it was highly likely that criminal elements would take that over – and that’s what happened. Guns were everywhere. Violence killed Manchester at that point.”

Today, the site of the Haçienda nightclub at Whitford St West is a luxury apartment complex. Though the original bricks and mortar are gone, the impact and legacy of what went before defines the city that Manchester is today.