Stephen Duffy talks Dr Calculus

By Anthony Reynolds | April 13, 2022

Stephen Duffy’s great lost album Designer Beatnik was part of the short-lived Dr Calculus project. In this interview from 2021, we take a look at the often overlooked experimental ode to emerging Ecstasy culture…

Britain, the summer of ’86 and Chris de Burgh bestrides both single and album charts led by The Lady In Red. Elsewhere, Wham! are saying goodbye and Paul Simon is popularising South African Mbaqanga music via his Graceland album. It’s at this point that Stephen ‘Tin Tin’ Duffy, sometime pop star, full-time genius, releases one of the strangest albums of his or anyone else’s career.

Designer Beatnik by Dr Calculus mdma is a sonic fantasia of cartoon dialogue, drum machines, mournful brass, funky bass and reversed strings. With no lead vocal melodies as such, it’s by turns chemically joyful (Blasted With Ecstasy) and crepuscular (Moments Of Being). The album came and went like an acid rush, leaving barely a hangover.

Thirty-five years later, Stephen Duffy is reminiscing about one of the most overlooked records of the 80s. “That album hasn’t been something I’ve thought about much,” he says from the comfy confines of his Cornwall home. “But it certainly was an amazing thing to do. The actual recording of it still informs what I do now, because we had so many ideas on that album. We did things like recording the snare drum with blankets over us.” That very snare sound can be heard on Swing Out Sister’s Breakout. “And we put the mix through the headphones and then miked that up…”

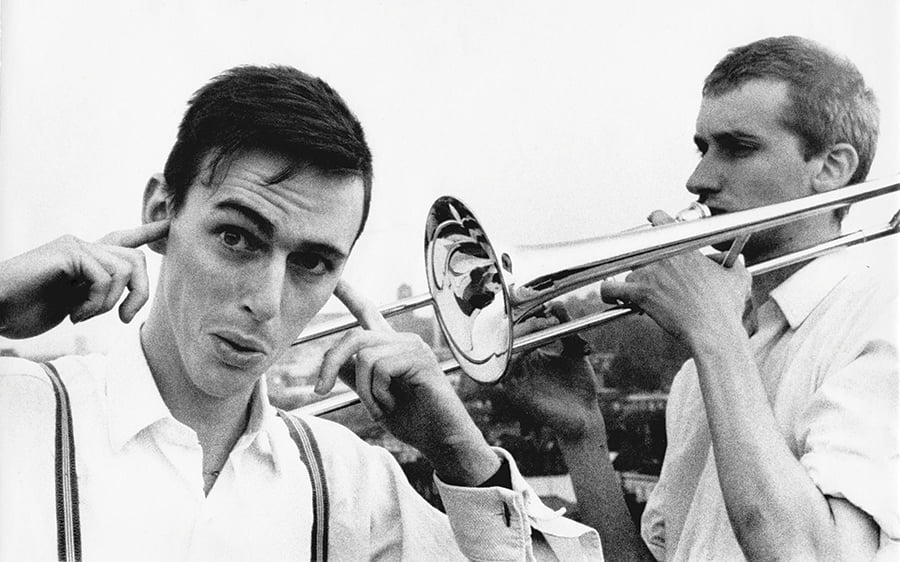

Duffy was aided and abetted by ex-Pigbag trombonist Roger Freeman. “I remember Stephen saying to producer and sound engineer Paul Staveley O’Duffy, ‘If you’ve ever wanted to try out anything and everything in the studio regarding effects but haven’t been allowed to – now’s your chance,’“ recalls Freeman.

Nick Duffy, brother of Stephen, contributed photography, design and violin to the album: “The 80s arrived with a disappointing message that it was time for the folk devils of the previous three decades to take a back seat while the yuppies tided things up,” he states. “Dr Calculus was having absolutely none of this. The delight of the emerging music technologies was how things could be torn up and re-scattered in spontaneous bricolage. It was the revenge of musique concrète and cut-up poetry. A ragged mélange of synthetic and found sounds, words and trombones.”

Released in the late summer of 1986 by Virgin subsidiary 10 Records, Designer Beatnik was greeted with bafflement. If at all. Stephen ‘Tin Tin’ Duffy – a bona fide pop star by then – was merely credited as another ensemble player in an enigmatic project. There were no accompanying videos or live dates and few interviews. Curiously there was a John Peel session in January ’85, which featured pre-recorded pieces. The album didn’t chart.

A single, Programme 7, had been released in January 1985, peaking at No.99 for one week. Duffy’s Kiss Me was released a month later, getting to No.4. Each track on Designer Beatnik segues into the next, forming a non-stop 40-minute piece, at times sounding like Madness – the group and the mental state – hijacking a Chicago 808 House party. Commercially, the album went nowhere. But where did it come from?

Stephen Duffy: “It started off with Roger. I knew him from Birmingham. By now, he’d left Pigbag but Papa’s Got A Brand New Pigbag was a huge hit record. I knew there was something worth pursuing there. By 1984, we’d all moved to London and hooked up again.

“He mentioned to me that he’d been going to this club, where they’d been playing this crazy electronic music and everybody was taking drugs. This was the beginning of Ecstasy culture in London, I would imagine. I went along to some of these clubs with him, then one morning after we sat down and said, ‘Okay, let’s do something about this.’“

Roger Freeman: “We met up in the White Trash club, off Burlington Arcade in London. In between Stephen recording his The Ups And Downs album on Richard Branson’s narrow-boat studio near Warwick Avenue we dashed off Programme 7. Before I know it Stephen’s got us a contract with the 10 Records label.” This isn’t as incongruous as it sounds. As Virgin’s Managing Director Simon Draper once acknowledged: “Virgin has a history of outré acts, from Mike Oldfield to Henry Cow. We weren’t just all about Phil Collins.”

Read more: Stephen Duffy interview

Duffy adds: “We immediately stopped recording The Ups And Downs and when we did Programme 7, I just thought, ‘Well, this is kind of exciting. Let’s pursue this.’ I didn’t ask Virgin for permission, we just started recording it. Then I must have sent the tapes accidentally back to Virgin and, after being a little peeved, they decided they liked it. It became a natural ‘happening’. They signed the project and we put out Programme 7, which caused a bit of a buzz. Later on, Perfume From Spain would get a release. The rest of the album just happened…”

Programme 7 was picked up by some regional radio stations and more importantly by John Peel who’d then invite the ‘band’ to the aforementioned session. …Spain would appear nearly two years later in a slightly different form and retitled Full Of Love in the John Hughes film She’s Having A Baby.

Freeman: “What made the album open to all possibilities was the fact that the Dr Calculus contract didn’t affect Stephen’s separate ‘serious’ career contract with Virgin. Therefore he didn’t care how wild the recording got. This included keeping all the funny mistakes, accidents, dirty words and moods. For example, our friend Françoise Gigandet can be heard mispronouncing ‘spinning‘ as ‘spining‘ on Killed By Poetry.

Producer Paul also shoved Chris Lee’s trumpets through an effect called a 3D panner, which turned out to sound brilliantly trippy. This ‘free’ approach extended to adopting the name ‘Dr‘ instead of ‘Professor‘ Calculus – which is the actual moniker in the Tin Tin comics. A friend mistakenly said ‘Dr’ when coming up for a name for the band – which was better because we could then add ‘mdma‘ after it.” (More on mdma later.)

However, the album was far more than a mere freaky free-for-all. Mixed in with the techno jitterbug and Looney Tunes samples was beautiful live brass evoking the spirit of Miles Davis and Gil Evans. This was down to the contributions of other ex-Pigbag players. “There was the sax player Olly Moore on baritone and tenor sax. Chris Lee on trumpet. They were good players,” reflects Duffy.

“It’s funny when you think back to London then, in the mid-80s. There was a jazz thing; Working Week, Light Of The World, Sade… all converging at The Wag Club. But Pigbag had been far more gritty; they were in denim while the mid-80s lot were wearing Paul Smith suits.”

Freeman: “Pigbag trumpeter Chris Lee was the most knowledgeable about contemporary jazz out of all of us and had a large album collection. The track Designer Beatnik itself was built up by me doing my Westminster clock chimes impression on the trombone to a basic drum machine guide. Chris had worked out a multi-layered chord sequence on his trumpet.

“While me and Stephen went away to play pool in another room, the producer was left to record Chris playing trumpet over and over again. Afterwards, everyone had a crazed look in their eyes. When it came to mixing, Paul had obviously cracked, which worked in the album’s favour.”

Designer Beatnik is effervescent with ideas and yet oddly, when compared to the rest of Duffy’s catalogue, the one thing deliberately missing is lead vocal melodies. Duffy himself does not sing on the record. “There’s no singing on Designer Beatnik as such,” explains Duffy. “If there is, it’s a female voice. But it wasn’t about vocal melodies. Any melodies were always going to be on the trombone. Roger was going to come up with the riffs and I was going to do the rest.

“Lyrically, we were trying to create a French New Wave sound. We were quoting texts by Jacques Tati, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Shakespeare, Jean Cocteau. Quite literally. We were cutting up their actual quotes and collaging them.”

“I got my friend Françoise Gigandet to speak lyrics in her French accent,” adds Freeman. “Stephen gets in his fashion model friends to recite lyrics. Other speech was taken from radio and TV and the sound effects from the Emulator sample keyboard. The sounds of walking on gravel, talking and laughing must be the fashion model – and then Stephen’s girlfriend – Tamsin De Roemer with their recording Walkmans in Japan. There’s also some Japanese TV in there on the track Man.“

When asked about the predominance of female fashion models appearing on the album, Duffy laughs: “I was a pop star in the 80s. It’s what was expected of me!”

By the latter stages of recording the album Duffy had scored big as ‘Tin Tin’ and experienced all of the madness that comes with having a hit record.

“Some of the Designer Beatnik sessions were informed by me going to Japan,” he recalls, “where I had the proper ‘pop star treatment’ – screaming girls and all of that. Me and Tamsin also had these new toys – recording Walkmans – which we used to document our trip.”

Asides from the models, others present in the studio were both more obscure and well known. “Japanese keyboard player Izumi Kobayashi came in for a day,” recalls Freeman, “at one stage saying, ‘I see this piece of music as a very round ball’ (Stephen and me exchanged nervous glances). In the middle of all this, Terence Trent D’Arby and his manager walk into the studio to say hello, take one look at us and walk straight out. By now we were in a large basement studio in Victoria. We then moved to SARM West studios in Notting Hill to do the mixing.”

Amongst the joyful Jackson Pollock spatter of the album, a beautiful requiem appears. Moments Of Being (Reprisal) evokes long summer shadows over English lawns at dusk with the final Pimms of the day. Its composition was rather more prosaic. “That track came about when [model] Caroline Dodd and me were chatting in front of a mic in between takes and Stephen asked the tape to roll,” says Freeman. “He then chucked on the reversed orchestral part from his Julie Christie track.”

Underpinning the entire album is a queasy, dream-like atmosphere provided by the cartoon dialogue samples. A mood which in itself was inspired less by drugs and more by a VHS tape that happened to be hanging around.

“While we were making the record, we had a video of Jonathan Miller’s Alice In Wonderland on in the background,” explains Duffy. “I didn’t actually take ecstasy while making the album and only started taking it after we started recording it.

“What’s insane is that ultimately it got me back into acoustic music. The first time I took ecstasy, was the first time I heard River Man by Nick Drake. I was laying down on this lawn and Nick Laird-Clowes from The Dream Academy had it on a boom-box and he put it next to my head. I heard Nick Drake singing, ’Going to see the river man/ Going to tell him all I can/ About the plan/ For lilac time.’ It was just like, ‘Okay, I know what I want to do now. I want to go back to acoustic music.’”

Meanwhile, the album – housed in a beguiling cover in bootleg orange by Nick Duffy showing the reversed image of the Spirit Of Ecstasy’s statuette on Marc Bolan’s Rolls-Royce – was released to vague indifference and bewilderment: “A musical rag bag of eccentric sounds and commentary…” reckoned Record Mirror, “…it isn’t necessarily something you’re going to want to give continuous rotation to.”

“When the album came out, I think it was just too much for people to get their heads around,” reasons Duffy. “There was one review that said, ’This record must have been more fun to make than it is to listen to.’ We didn’t even get any feedback from other musicians. People who generally like my music, don’t like this record.”

“That summer, I saw the Dr Calculus album in the Virgin Megastore on Oxford Street,” laments Freeman, “and then… nothing.”

Duffy: “We did start recording another track after the …Beatnik sessions; Wild Bohemians. But it wasn’t working.”

For Duffy, many adventures still lay in store. “One track I did with Robbie Williams called Tripping was basically Perfume From Spain speeded up. But generally, my music became more conventional. After Dr Calculus, I didn’t need to experiment anymore.”

Read more: Clare Grogan interview