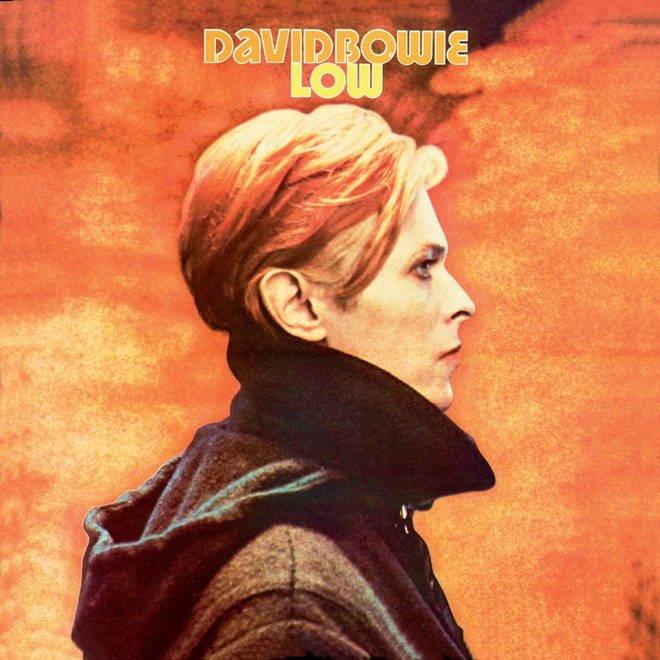

David Bowie Low cover

In 1976 David Bowie fled his demons, seeking seclusion, healing and creative freedom. he landed in Germany and set about creating the first album of his celebrated ‘Berlin trilogy’, the mighty Low…

Though Bowie had finally achieved his long-sought goal of gaining chart success in America, it had come at a cost. The laid-back sophistication of Young Americans had morphed into the destabilised desperation of the still utterly marvellous Station To Station.

The latter album was a sonically and lyrically textured masterpiece, but psychologically Bowie was somewhere else entirely – indeed, he would later claim to not remember recording it at all.

A now-crippling dependence on cocaine had addled Bowie’s mind, and his stylistic adoption of the consciously dark Thin White Duke persona had now swamped his being more thoroughly and totally than even his earlier situation with the Ziggy Stardust character had.

Bowie fled to Switzerland in an effort to be free of this evil twin, his dependence on drugs and the vacuity of his former Los Angeles home.

His first project was to work with his good friend Iggy Pop, who had a range of predicaments to work through himself, and Bowie’s behind-the-scenes puppet mastery on the iconic The Idiot opened many musical doors that led Bowie directly onto his work on Low – which was initially titled New Music: Night And Day.

Low’s dynamic and sonic adventurousness can be partly attributed to Bowie’s tight relationship with his latest creative muse Brian Eno, who would inspire Bowie and his band to explore a range of new approaches to songwriting, performing and mixing that would shape the Berlin Trilogy’s creative process.

Though Bowie and Eno’s relationship was a major piece of the creative jigsaw, another important element was Tony Visconti’s production, utilising such innovative sonic tools as the Eventide Harmonizer, which Visconti radically applied to many of the drum tracks on the record.

Aside from the addition of versatile lead guitarist Ricky Gardiner, the core band remained pretty much unchanged from Station To Station. It included rhythm guitarist Carlos Alomar, who remembered: “All cards were off the table for this album. We knew that Brian was running the show.

“Visconti and I had brought all our effects. I had footswitches, bypass phasers and Tony had his toys. Brian had a synth that had a magnetic ribbon hanging from it. I later found that he could connect with it, somehow, through this ribbon and have it sequence. Pure genius.”

Read more: Making “Heroes”

Read more: Making David Bowie’s Let’s Dance

The record is divided into two distinct halves. The more conventional songs fill up most of Side One’s running time, while the second side is wholly instrumental in nature, with these nuanced arrangements dominated by textured EMS synth.

On the few songs that Bowie does lend his vocals to on the record, we tend to get lyrics that are fragmentary and which thematically offer shattered pictures of a life in turmoil.

Opening instrumental Speed Of Life is a brief sonic preview of all that’s to follow, including a fade in/fade out that’s used on many of the tracks on Low, giving the listener the impression that doors are being opened and closed, and that somewhere, this unresolved music is still playing.

Breaking Glass follows, a painfully resurrected memory of a relationship, and a mind, in strife, while the poppier learnings of What In The World offer up a depressing, agoraphobic lyric that speaks of yearning for love, though seen through the eyes of a dark lyrical protagonist “talking through the gloom” and waiting “until the crowd goes”.

Similar subject matter is dealt with in one of Bowie’s finest songs, Sound And Vision. The song’s scant lyrics serve as a paean to inspiration, and thus represent the sonic distillation of everything he sought to achieve with Low.

However, the themes of the song also highlight the utter blank misery of depression, with the “pale blinds drawn all day, nothing to do, nothing to say” in Bowie’s isolated room. These lyrics, and Bowie’s irregular delivery, are contrasted by the track’s upbeat arrangement, the “doo-doo-doo” backing vocals, and the nursery-rhyme-like descending melody.

Elsewhere on Side One, Always Crashing In The Same Car is a weary and resigned piece that references the relentless cycle of Bowie’s dismal mental state as well as an unfortunate incident with his Mercedes, where the singer rammed a car that belonged to a coke dealer who had ripped him off. Be My Wife is an anguished plea for companionship, complicated by Bowie’s inability to stay in one place too long, both geographically and musically.

Read more: The alternative David Bowie Top 20 – 1975-’80

Read more: The alternative David Bowie Top 20 – 1981–’93

While two of the songs proper sit among the finest of Bowie’s entire career, it’s the instrumental side where Low comes into its own, particularly when viewed as a unique listening experience. The instrumentals, which really begin with Side One’s poignant closer A New Career In A New Town, offer a broad collage of both sonic succour and despair, in a less internalised form.

On Side Two, Bowie turns his attentions beyond himself and instead paints a picture of the various cultures, communities and cities that surrounded him, from the solemn Warszawa’s bleak evocation of the Warsaw that Bowie encountered while travelling through the city the preceding year to the punsomely-titled Art Decade (perhaps the first Berlin-oriented piece of the trilogy), which illustrates the disengagement of West Berlin society at that time, when it was by-and-large a hedonistic, culturally malnourished environment.

The other side of the city’s wall is invoked by the album closer Subterraneans, a harrowing sonic eulogy to those who were caught in East Berlin after the separation.

These two pieces are deliberately divided by the spine-tingling Weeping Wall, serving as the aural equivalent of that imposing dividing line, with a multi-instrumental arrangement that contains guitar, vibraphone and piano.

Initial reaction to the record was somewhat baffled. This was the year of the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind The Bollocks in the UK, and the US market expected the further funky exploits of the chat show-friendly Bowie of 1976.

But Low has since come to be regarded as one of Bowie’s central works: it’s honest, raw and anguished, but Bowie’s mission here is to move beyond this state of mind, attempting an exorcism of his demons via music. In this sense, Low is a positive record.

The rich instrumental work on the album shows Bowie’s desire to explore music in an advanced and original way, particularly for a major pop star. He’d continue this approach on Heroes later the same year, demonstrating he’d indeed found the sound and vision he evangelised on the eponymous lead single.

Low is an important record in a broader context, too, impacting on the mindsets of many young Bowie-heads who would take on the spirit of musical (and conceptual) audacity and push those ideas into the mainstream, as well as throwing a spotlight on many of the electronic inspirations Bowie and Eno revered.

No doubt, it helped mould the synthesiser into an object of ‘cool’.

Is Low David Bowie’s best album? Well, that’s one of those perpetual debates that shifts and alters as trends and perspectives change – but it’s a fascinating collection and undeniably one of his most transcendent, superlative listening experiences.

David Bowie: Low – the songs

Speed Of Life

Propelled out of the ether by a whirling buzz of Eno’s quickly faded-up synthesiser, bold instrumental opener Speed Of Life exhibits many of Low’s sonic facets. There’s the impactful rhythm section – Dennis Davis’ processed drum sound, the inconspicuous but effortless bass playing of George Murray, the fizzing synth that increasingly dominates and a cyclic, tightly structured arrangement. Before we can get too comfortable, the track moves into a fade out, making for a tantalisingly unresolved listening experience.

Breaking Glass

“David and Angie had been arguing and it was easy to hear what was going on, so the music of the song needed to represent the way people argue,” Carlos Alomar remembers about this Low highlight. “I really thought out the arrangement. The drums and bass start out like somebody knocking on the door, hard.”

While Breaking Glass is the shortest song on Low, it’s one of the record’s most memorable moments. From the infectious lead riff to the tight (yet unsure) funk arrangement that bounces to life during the verses, to Bowie’s lyrical shards and yelps of histrionic self-reflection, Breaking Glass finds Bowie laying bare his pained mindset. Though the lyrics are few, they work incredibly effectively, including the provocative: “You’re such a wonderful person, but you’ve got problems…”

What In The World

Originating as a track earmarked for inclusion on The Idiot, Iggy Pop appropriately lends vocals to this relatively upbeat track that is among the more commercially flavoured compositions on Low. Despite this, the arrangement and mix are occasionally challenging, from the chirruping synthesiser, providing a futuristic veneer, to the unsettling, isolated lyrics that imply a yearning to escape and find love. Once again, the lyrics and allusions are fragmentary.

Sound And Vision

The album’s lead single is also among its high water marks – some would argue it’s one of the highlights of the entire Berlin creative endeavour. Sound And Vision is, on the surface, an incongruously breezy and buoyant pop song, with an upbeat but reflective feel. This relatively straightforward arrangement is impaled by shards of descending synthesiser, which stream into the song like the sonic equivalent of sunlight beaming into a dimly-lit room – the same kind of room, perhaps, as the one that’s evoked by a sublime but brief lyric which, though gloomy, is ultimately a positive manifesto that distils Bowie’s creative approach to his album entirely into one song.

Bowie searches for a creative muse, going cold turkey on distractions and vices and focusing on achieving “the gift of sound and vision”. Though the song was inspired by this sense of inner turmoil, it’s nonetheless extremely infectious, making it one of the most accessible pieces of music recorded during the Berlin period. This was reflected by its No.3 chart placing in the UK singles chart.

Always Crashing In The Same Car

A haunting, shimmering song that (unusually for Low) starts and ends with no fades, Always Crashing In The Same Car is a beautifully elaborate piece of music that highlights both Ricky Gardiner’s sublime lead guitar skills as well as Eno’s multi-layered synthesis. Bowie once again sings with sad uncertainty, though the despondency evoked in the resigned lyric is in the past tense, perhaps implying that this state of mind is consigned to memory. However you read it, Always Crashing… is one of the most glorious compositions on the record.

Be My Wife

With an over-the-top piano dominating proceedings, Be My Wife finds Bowie romantically yearning for love with a lyric that also heavily references his wanderlust (this would be a more pronounced concern on 1979’s Lodger). Be My Wife is perhaps the oddest song on Low, even though it’s one of the more accessible and conventionally structured songs. An interesting choice for a single, then – which perhaps explains why, when it was released shortly after Sound And Vision, it failed to chart in the US. The garage-band style and vaguely intoxicated air that pervades Be My Wife would be resurrected again during the Berlin Trilogy, and is also an interesting sonic precursor to the kind of sound that Blur adopted in the late 90s.

A New Career In A New Town

This ghostly, evocative instrumental segues Side One neatly into the (relatively) vocal-free Side Two. It’s a moving, transitional piece, as the title reflects. The wonderful harmonica work serves as a despairing human wail in the dark, counterpointed with the sluggish mechanisation of the repetitive rhythm section. This harmonica line would be reused later in Bowie’s recording career, on the title track of 1987’s Never Let Me Down and on the heartbreaking, triumphant closer of 2016’s Blackstar: I Can’t Give Everything Away.

Warszawa

And so to Side Two – the experimental milestone that astounded and dumbfounded in equal measure. Warszawa begins what is, in essence, a travelogue. Here, we’re taking a look at the Warsaw of the mid-70s. Bowie would say that the second half of Low contained tracks that concerned things he couldn’t put into words and “required textures” – and here, in a mournful and solemn-feeling track, Bowie and Eno do just that. Through the synth, we zone into the mood of a particular place and a time. Bowie would add the bizarre, lyric-free vocal after the composition, with Visconti speeding up the tape to raise his register.

Art Decade

This eerie, nostalgic piece evokes better days – as the obvious pun in the title implies. Art (ie, culture, society) had decayed on the western side of the Berlin Wall, the former glory of the city now a fading memory of yesterday. Though Eno composed much of the initial arrangement in solitude, Bowie contributed to establishing the tension of the track, and the addition of real instruments – included a gorgeous cello – contributed to the impression of former glory.

Weeping Wall

Eno might have played a big hand in the shaping of the previous two tracks, but Weeping Wall was a solo exercise for Bowie who, entirely alone, created this sonic reaction to the ever-imposing presence of the Berlin Wall, and its divisive effect on the city’s inhabitants. It was also the only track on Low to be recorded entirely at Hansa Studios in Berlin, with a view that directly faced the wall. It’s a distorted jumble of melodic ideas and occasional vocal snapshots – evoking, perhaps, the graffiti and snippets of human communication that covered the wall itself.

Subterraneans

Originating as a piece of music intended to soundtrack The Man Who Fell To Earth, Subterraneans was worked on further and grew into this fitting closer for the record. Conceptually, it’s a reference – and a salutation – to the forgotten families and lives that resided on the other side of the wall, in Communist East Berlin. The backwards music and the faint-jazz effect of the distant saxophones are unsettling as well as being sonically fascinating, as are moody chant-like vocals that are conjured from the ether. It’s a tense piece that closes without resolution, ending Low on a stunningly moving note.

Read more: Top 40 New Romantic songs

David Bowie’s official website

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.