Run-DMC Interview – “The greatest period in hip-hop was the time before recorded rap”

By Classic Pop | June 23, 2022

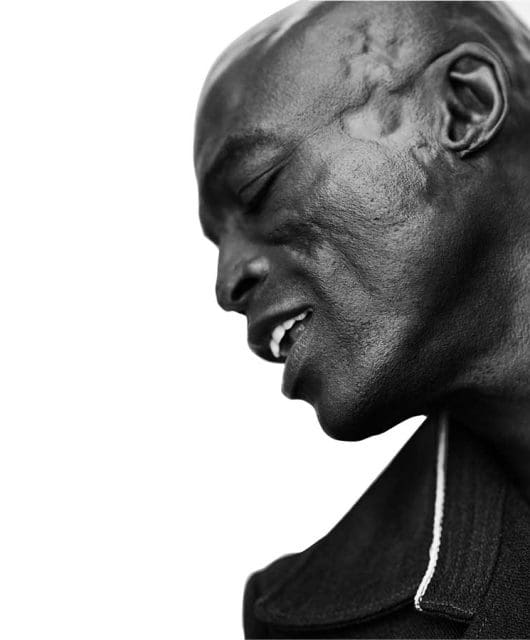

Run-DMC took hip-hop to the mainstream VIA crossover classics Walk This Way and It’s Tricky, but split after the death of Jam Master Jay in 2002. In 2021, rapper DMC talked to Classic Pop about his time in one of the most seminal rap groups of all time… By Will “ill Will” Lavin

Run-DMC took hip-hop to the mainstream VIA crossover classics Walk This Way and It’s Tricky, but split after the death of Jam Master Jay in 2002. In 2021, rapper DMC talked to Classic Pop about his time in one of the most seminal rap groups of all time… By Will “ill Will” Lavin

It’s not often that a hip-hop icon will rap for someone one-on-one, but that’s exactly what happens when Classic Pop asks Darryl “DMC” McDaniels of Run-DMC what we should call him at the start of our Zoom chat.

“You could call me Darryl, you could call me D/ You could call me Darryl Mack, you could call me DMC,” he begins, tweaking the lyrics to the title track from the group’s 1985 album, King Of Rock.

“People always ask me what does my name mean/ D’s for never dirty, MC’s for Mr Clean/ But sometimes I tell them when certain people ask/ That DMC means that Darryl makes cash.” As far as introductions go, it’s up there with the best of them. And as far as his name, we settle on D.

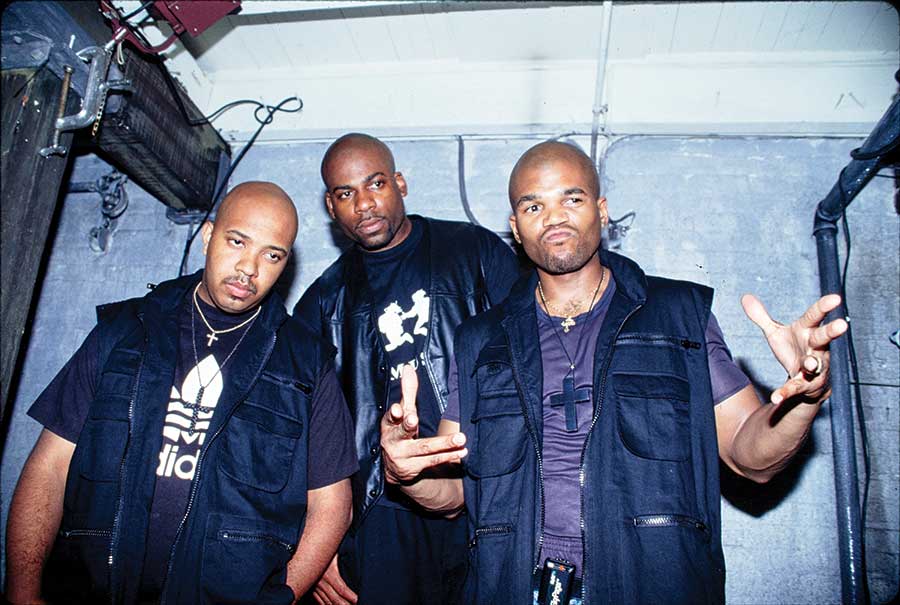

It’s been 40 years since DMC and his bandmates, Joseph “DJ Run” Simmons and the late Jason “Jam Master Jay” Mizell, came together in the New York suburb of Hollis, Queens, to form Run-DMC.

Often regarded – rightly so – as one of the most influential groups of all time, through their hard-hitting reality raps, gut-busting beats and innovative fashions (Adidas, anyone?), the trio helped cut through racial barriers and catapult hip-hop onto a global stage, making way for a new creative force that continues to dominate pop culture today.

Besides being the first hip-hop act to be nominated for a Grammy – for Best R&B Vocal Performance By A Group – for Raising Hell in 1986, Run-DMC were also the first to appear on MTV, on American Bandstand, Saturday Night Live and the cover of Rolling Stone.

In 2009, they further cemented their legacy when they were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. But, for all their accolades, DMC is quick to point out there were many artists before them who played a big part in their jet-fuelled, meteoric rise.

“People don’t understand that the greatest period in hip-hop was the time before recorded rap,” DMC says. He adds that, while some people credit Run-DMC with starting hip-hop, there were many artists doing it in the streets way before the trio took it to the mainstream.

Speaking of their seminal 1986 cover of Aerosmith’s hit from 11 years earlier, DMC recalls: “Before we made Walk This Way, Melle Mel and Kool Moe Dee rapped over the track. They just never did it on a record.” While that may be true, it was Run-DMC’s version which would become one of the biggest-selling hip-hop tracks of the 80s.

Run-DMC’s latest release sees them collaborate with boutique vinyl brand 12on12 to curate an exclusive limited edition 12″ compilation, complete with bespoke artwork from rising LA artist Reena Tolentino (aka RT).

Offering a fascinating insight into the group’s influences, it highlights early rap trailblazers as well as songs that helped form the sonic foundations of a burgeoning hip-hop sound as it emerged and evolved in New York in the late 70s and early 80s.

“It’s just a fraction of the hundreds of songs that allowed us to exist,” DMC explains. “These songs define not just our childhood, but our existence during a time of death, destruction, despair and struggle. When you go back to that time period, the Bronx was burning.

“We had to make something out of nothing,” he says, remembering hip-hop’s early inception. “Well, people thought we had nothing but in fact we had everything. The songs that were playing around us at the time, we had to utilise in order to show the world who we are.

“So before [The Sugarhill Gang’s] Rapper’s Delight, before [Afrika Bambaataa And The Soulsonic Force’s] Planet Rock, before we were sampling, we would use this white group from Germany, Kraftwerk. We used their sonic vibe because it felt exactly the same way that we were feeling.”

Kraftwerk wielded an enormous influence on the early years of rap and beyond. From Afrika Bambaataa, The Fearless Four and Sir Mix-A-Lot, to more recent artists like Busta Rhymes, Jay-Z and Wu-Tang Clan’s Raekwon, the German giants are forever woven into the fabric of hip-hop, which is why their 1977 classic Trans-Europe Express features on Run-DMC’s 12on12 compilation.

“They are the foundation,” DMC says. “There is no hip-hop without James Brown or Kraftwerk.”

Another track that was instrumental in the early growth of hip-hop chosen for Run-DMC’s playlist is Chic’s 1979 classic Good Times. Its deep, resonant bass riff and string stabs wound up being the foundation upon which rap’s first hit single, Rapper’s Delight, was built.

Used without permission, Chic’s Nile Rodgers and the late Bernard Edwards threatened to sue Sugar Hill Records for copyright infringement. A settlement was later reached that gave Rodgers and Edwards songwriting credits.

“I never liked Rapper’s Delight, because it didn’t sound like Good Times,” DMC admits, explaining he wasn’t a fan of the label’s decision to have the track reproduced, as opposed to sampling the original. “We were mad that Sugar Hill Records didn’t use the real one. With them replaying it, they took away the realness of it. It sounded plastic and corny.”

DMC thinks back to the 70s, when DJs Grand Wizzard Theodore and Grandmaster Flash played Chic’s original break at block parties, and how “hard” the record sounded.

DMC and Def Jam Records co-founder Rick Rubin often discuss the superiority of Good Times. “Even though it was a disco record, it was hard,” explains DMC. “We thought Rapper’s Delight was fake, because it didn’t sound like Nile’s. It sounded way too clean.”

As the purpose of the group’s new compilation is to shine a light on some of the most important songs to influence hip-hop’s early beginnings, it wouldn’t be right not to include Run-DMC’s own Rock Box.

The 1984 track brought rock and rap together for the first time, in a genre-defining moment that helped rap cross over to the mainstream, as well as breaking down colour barriers, which paved the way for a new wave of Black artists to take over the airwaves for years to come.

But things could have been so different if Run and DMC had had their way. “We didn’t like it at first,” admits DMC, revealing that producer Larry Smith and Jam Master Jay were responsible for fighting to keep it the crossover behemoth that it is today.

“Me and Run were thinking from a limited hip-hop perspective. It was supposed to just be the beat, and then the guitars were supposed to come in and play for maybe four to eight bars. We wanted it to be like the hip-hop in the park. We wanted to be the church of the street, not realising we could be The Rolling Stones.”

The addition of Eddie Martinez’s riff – which many regard as the hip-hop equivalent to Eddie Van Halen’s riff on Michael Jackson’s Beat It – turned Run-DMC’s little hip-hop in the park idea into a timeless rock‘n’roll stadium anthem. It also paved the way for their even bigger rock-rap crossover, Walk This Way, with Aerosmith. “There is no Walk This Way if there’s no Rock Box,” DMC maintains.

Other tracks on the 12on12 compilation include The Sugarhill Gang’s Apache (Jump On It), MFSB’s Love Is The Message and Seven Minutes Of Funk by The Whole Darn Family, which was famously sampled on Ain’t No N***a for Jay-Z’s 1996 debut album Reasonable Doubt.

One song that appears that might surprise some is Kenny G’s The Look Of Love. Although he’s been enjoying a resurgence as of late, thanks to recent collaborations with the likes of Kanye West (Use This Gospel) and The Weeknd (In Your Eyes), for years Kenny G – who started his career playing as part of Barry White’s Love Unlimited Orchestra – has been the butt of countless jokes.

The mainstream has long cracked jokes that Kenny makes elevator music; there are hundreds of Facebook groups claiming he killed jazz because of his smooth sound.

DMC doesn’t entertain the criticism. “Kenny G is on there because it’s music,” he boldly states. “He’s got some great riffs and lines that we can sample. People think we’re just about James Brown, Kraftwerk and beats. No, it’s Bob James’ Take Me To The Mardi Gras. It’s Rush’s Tom Sawyer, it’s Toto. It’s little orphan Annie’s Hard Knock Life. Why would anyone think that these hard B-Boys from the city wouldn’t listen to some Kenny G?”

The saxophonist’s inclusion on the playlist is also a homage to Run-DMC’s long-time DJ, Jam Master Jay, who was murdered in his recording studio in 2002. “We wanted to put something on there that Jay would have picked,” DMC explains.

“You’ve got to understand, when people look at DJs – and this is where racism, separation and ignorance is funny – they will look at this young, Black man and assume he knows nothing about jazz or opera. There’s a stereotype there. But in fact the best producers are DJs and musicians because they know a thing or two about music.”

Of course, Jay’s bread and butter was rap, his ear always firmly fixed to what the streets were doing. Instrumental in developing the careers of Onyx – whose 1993 track Slam is a quintessential hip-hop anthem – and 50 Cent, Jay worked with many artists via his own label, JMJ Records. Even though rap’s landscape has changed hugely since his death, DMC thinks his former DJ would have been right in the thick of things if he were still alive.

“Jay would be producing all of these guys right now. He’d have a ‘Young’ this, a ‘Lil’ that,” he says, referencing the names favoured by many of today’s rappers. “There’s no question Jay would have a Lil Baby or an artist like that right now. He’d definitely have a label position, too.”

Underscoring Jay’s importance to Run-DMC, DMC adds: “If you look at our evolution, Jay was always the one that transformed into what was happening at the time. If you look at Jay’s style, he was the guy that got dreads. He was the guy that got braids. The way Run-DMC dressed, that was because of him.”

Before DMC jumps off the call, there’s one final question that needs to be answered. Being that it’s been 20 years since Run-DMC put out Crown Royal, their seventh and final album, have the surviving members talked about lacing up their Adidas once more to do another album?

“It can’t happen,” DMC says, pointing out the lack of Jay’s presence behind the turntables. “That’s like trying to put The Beatles back together without John and George. You just can’t do it.”