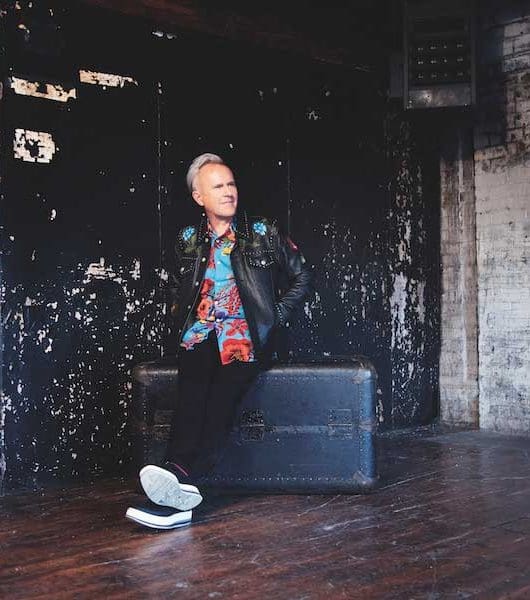

Teenage Kicks: Dave Stewart interview

By John Earls | July 8, 2022

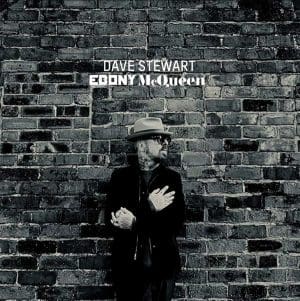

One of the music world’s great adventurers, even by Dave Stewart’s standards his new project Ebony McQueen is ambitious: a movie with an accompanying triple-album boxset. It also allows him to reflect on how a football-obsessed Sunderland teenager became one of pop’s great collaborators. In a wide-ranging interview taking in drunk pirates in the Caribbean and Bob Dylan’s love of cocktails, he tells us: “I’ve got an inquisitive mind.”

When Dave Stewart sat down to pen his autobiography Sweet Dreams Are Made Of This in 2016, he faced a major problem. “I was bored writing about my life after Eurythmics,” he admits. “I preferred writing about my life before, about growing up.”

Dave isn’t one for detailed plans, but the chance to write about the pivotal time when music came into his life has now inspired Ebony McQueen – a fantastical film and boxset of how Stewart swapped his obsession for football into becoming a piratical adventurer in music, from teenage folkie via synth-pop overlord to restless genre investigator.

The inspiration for the project was meeting a woman named Ebony McQueen while Dave was out on his bike near his home in the Bahamas. He recalls: “As I cycled home, I began singing: ‘Ebony McQueen, I think I met her once inside a time machine.’” More lyrics arrived for the absurdly catchy, almost nursery rhyme melody.

“When I got home, I began thinking about using an orchestra, this song getting bigger and bigger in my head, while I’m in the basement of our 200-year-old house, where drunken pirates would be tossed years ago. I realised the song was becoming autobiographical, I thought: ‘Hmm, that’s interesting. How did I start this journey?’”

Talking to Classic Pop in his suite at fashionable London hotel Ham Yard, the next two hours are a brilliant voyage of discovery. Dave doesn’t so much answer questions as use them as jumping off points for the next idea to arrive in his bustling mind. He’s a brilliant one-off, sweet, funny and unguarded.

“I’ve got a million stories like that,” says Stewart after remembering how he sang Many Rivers To Cross at 2am on German radio with Jimmy Cliff while the pair were drunk. He’s right – Dave’s life seems a guide for how many adventures it’s possible to fit in, if you’re up for a laugh.

“My mam said I could be very tiring,” he smiles. “She’d be washing up when suddenly a bird’s nest would come flying in the window while I’d be shouting: ‘Worms!’ and run off, on to the next thing. I’ve got an inquisitive mind.”

With so much going on in Dave’s head, he found it easiest to become obsessed, lasering in on one area of focus. At first, it was football. He played three games a day, hoping to get signed by his local team, Sunderland. Then, in 1965, aged 13, a bad tackle shattered Dave’s knee.

“When I woke up in hospital, the surgeon said: ‘Don’t worry, son, you’ll be playing football again in a year,” remembers Dave, showing us the scar. “But when you’re 13, a year is forever. And the atmosphere at home was depressing, because mam had left.”

This mood inspired the self-explanatory What’s The Fucking Point? on Ebony McQueen. “When your mam has left and you’re at home with nothing to do when you should be at school, life can be bleak and vacuous,” he reasons. “Sunderland has grey skies a lot of the time and I started getting the beginnings of a depression. I was staying in bed for ages, thinking, ‘I don’t get it. Is this what life is, just being here?’”

Even though his life is as rich as can be, Dave discloses that he’s essentially melancholic. “If you’ve got an inquisitive mind, you can’t suddenly switch it off,” he explains. “You don’t go, ‘Right, now I’m going to go over there and relax.’ Tranquillity and being at peace with myself after all the stuff that’s gone on in my life would be good, but I don’t think there’s any hope of that.”

Spoiler alert: music proved to be Stewart’s salvation. Dave’s older brother John played in a band covering Woody Guthrie and their cousin Ian was a blues obsessive who, at 13, adopted a Memphis drawl. “You can imagine the response,” laughs Dave.

“All the other kids were going: ‘Shut the fuck up, talk properly!’ Ian didn’t care and, as soon as he was 18, he was gone to Memphis. He’s still there. When I made my blues film Deep Blues, Ian helped find some of the locations in Memphis. His drawl is really strong now, you’d never guess he was from Sunderland.”

Read more: Essential Eurythmics songs

One day, a box of blues albums arrived for Ian. Dave had grown up listening to his father’s collection of musical soundtracks by Rogers & Hammerstein such as The King And I. “I put on one of Ian’s blues albums and hearing, ‘Weeelll!’ in an empty house in Sunderland, I thought, ‘What’s this?’ It sounded like magic, which of course it absolutely was.”

Football never returned – “I was dedicated enough, but I’d have found out at 15 I didn’t have the talent” – and Dave began begging to get in to local gigs. Sunderland’s folk club was having none of it, but Stewart was allowed to sneak into shows at The Rose And Crown pub. Aged 15, he left home to become part of folk band The Amazing Blondel. “I realised that holding a guitar was like having Excalibur in my hand,” he smiles.

It’s this period that the film of Ebony McQueen will focus on. Dave has been talking to various filmmakers – Netflix UK bigwig Fiona Lamptey; Borat and Life Of Pi producers Ingenious; Danny Boyle. “It could be a small independent film made in Sunderland, or it could explode bigger because it’s so fantastical,” ponders Dave. He’s already cast the love interest for the teenage Dave, Priya Prakash Varrier. Dave learned about her via a BBC News headline: “The actress whose wink stopped India,” after Priya’s cheeky wink in the 2019 film Oru Adaar Love scandalised conservative communities in the country. “She’s funny and outrageous,” enthuses Dave.

In examining Stewart’s teenage life, Ebony McQueen chronicles his troubled times trying to learn music in school. Mr Jolly remembers the overbearing music teacher who dismissed his dreams as “idiotic”. But it wasn’t all bad news.

“There’s always a hero in every school,” he reflects. “Mine was Dick Bradshaw. He taught English, but he was the first person to encourage my interest in music. I saw him playing bluesy jazz on the school piano and it was a revelation. I didn’t even know grown-ups could like music. The first record I ever made was a song Mr Bradshaw wrote.”

It led Dave to get his first interview, in the Sunderland Echo. He laughs: “At 15, I’d seen postcards of palm trees and I said to the paper: ‘I’m going to live in the Caribbean and teach guitar.’ And last year, I was teaching guitar to a bunch of kids near my house on a tropical island.”

Before the film, Ebony McQueen’s expansive soundtrack is out in May, as a triple-vinyl boxset also housing two 7″ singles and two cassettes. It’s a fabulous head-spinning journey, a wonderful tribute to the power of music. “The songs in the film keep the narrative going,” explains Dave. “The albums have other songs about those 12 weeks of my life when I discovered blues. There are songs like the title track which you won’t be able to get out of your head.”

As gorgeous as the Ebony McQueen package is, its records and cassettes are an old-school move from a musician who’s been at the forefront of technology. After all, Dave’s 1998 album SlyFi was one of the first to be released exclusively online. “I think I was the first person to release an album on the internet,” he insists mildly.

“David Bowie claimed he was first. Well, maybe… Very few people understood the possibilities then, certainly. It was another few years before Napster came along and showed what would happen. The speed to be able to download songs easily had caught up by then.”

He remembers convening a meeting with other musicians in the interim, wondering what could be done to protect musicians’ rights. Among the attendees were Stevie Wonder, Dr Dre, Bob Dylan, Quincy Jones and Lou Reed. While talking about terrible record deals, Stevie recalled how Motown wanted to drop him when he was still known as Little Stevie Wonder, because his voice had broken.

“Motown boss Berry Gordy’s son was there, too,” smiles Dave. “He was trying to stop Stevie from explaining how cut-throat his dad was. Stevie ignored him, telling everyone how he went home and wrote Uptight to try to stay positive.”

Even such powerhouses weren’t able to stop the juggernaut that led to the controversies around streaming royalties, but at least Dave had the foresight to see trouble ahead. “It can be hard being first, because the technology often isn’t there to back you up,” he reasons. “That means that not everyone will see the possibilities.” Nor is Dave a businessman. “I’m terrible with money,” he notes.

Dave’s attitude to cash was partly shaped by his stepfather, Julian. He met Dave’s mother Sadie while she was taking night classes, which eventually led to her getting a degree from Durham University and becoming a headteacher at a special needs school in London. “Julian was one of my big influences,” recalls Dave. “He was a zen Buddhist who didn’t want anything to do with materialistic things. My dad was amazing about it all, because he gave my mam away when she married Julian.”

Another admirer of Julian was Bob Dylan, when he and Dave were good friends in the 90s. “Mam and Julian lived in Maida Vale,” Dave remembers. “Before me and Bob would go to The Church studios, he’d say, ‘Shall we go and see your mother and Julian?’ Bob was fascinated by Julian, who wrote haikus. Bob’s favourite was: ‘This dunked biscuit/Will it, won’t it/ Reach my mouth?’”

Their friendship has been endlessly analysed by Dylanologists, but was in reality pretty simple. Stewart explains: “People assume we were making an album, but really we were messing about. We’d just have an interesting time, because he was having a bit of a break from being Bob Dylan. He’d sing songs around our kitchen table, wearing a Mexican hat and drinking margaritas.”

Such adventures have led to one of the great misconceptions about Dave Stewart. Asked what makes him such a good collaborator with other musicians, he beams: “I’m glad you ask that, because a lot of people say ‘Dave Stewart hangs around a lot of famous musicians’, as if I’m a hanger-on. Whether it’s Mick Jagger or Stevie Nicks, whoever, I’m inspired and excited about others’ ideas and I have the ability to inspire them in return.”

Dave says he listens to singers and lets them frame their melodies, rather than trying to force his accompaniment on them. “You could see that happening in the acoustic sections of Eurythmics shows,” he points out.

His old partnership with Annie Lennox also emphasises Dave’s abilities as a producer. “Producing is about bringing out the dynamics of a song,” he reasons. “When multi-track studios came in, people stopped mixing songs dynamically. Instead, people began balancing out all these channels.

“With Eurythmics, I went back to eight-track studios. Even when we recorded on 24-track studios, I’d only use eight. Our songs sounded exciting on the radio because Annie’s voice was so loud. You need to remember what should be emphasised. When Edith Piaf sings, nobody is saying, ‘But I can’t hear the drums.’”

It’s clear that Dave continues to have 25 great ideas before breakfast. He talks excitedly of plans for an album mixing acoustic guitar and orchestration. “Part of my personality is feeling that anything is possible,” he summarises. “Certain people like Annie have brought magic into my life. There’s a line in Ebony McQueen that totally sums it up for me: ‘What was real to me is whatever I thought it could be.’ I believe that, and it’s led me to have an incredible life.” And that’s Dave Stewart: living out a fantasy life in real time.

Read more: Eurythmics – album by album