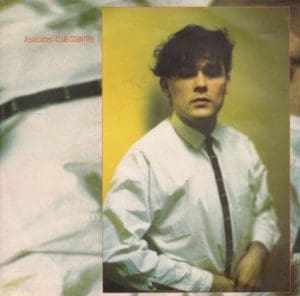

Post-punk pioneers the Associates transformed themselves into bona fide pop stars on 1982’s Sulk. Alan Rankine, Mike Hedges, Michael Dempsey and Martyn Ware take us inside their skewed masterwork…

Post-punk pioneers the Associates transformed themselves into bona fide pop stars on 1982’s Sulk. Alan Rankine, Mike Hedges, Michael Dempsey and Martyn Ware take us inside their skewed masterwork…

It’s a Sunday in Linlithgow during 1977. Alan Rankine sits at the piano in his parents’ lounge, it’s covered in Billy Mackenzie’s cigarette ash. Mackenzie travelled up from Dundee the night before, now the tea-sipping pair are nursing hangovers.

Out of nowhere, an elegant, infectious melody comes to Rankine at the ivories, as memorable as ABBA’s Dancing Queen’s from the previous year. It’s the start of a song that writes itself and a sure-fire hit. Just not now, at punk’s height, so the pair store it away safely for later use.

Skewed Masterwork

Fast forward to early 1982. The flash of inspiration in ’77, Party Fears Two, has catapulted the duo, now Associates, onto Top Of The Pops. Dry ice swamps the futuristic pipework-adorned stage. Mackenzie, clad in belted raincoat, dodgy hairdo concealed by black beret, is a star lost in his own little world, watching himself on the monitors, cheekily grinning as he shimmies.

Rankine, holding a banjo, is decked out in a fencing suit, Samurai make-up, chopsticks in his hair. It’s a thrilling, surreal sight beamed into millions of living rooms that Thursday night.

The timing for Party Fears Two is now perfect – it’ll peak at No.9 in the UK, another magical sign that anything’s possible in this new pop era. A few months later its parent album, Sulk, hailed as an instant masterpiece, will also storm the Top 10. For six or so glorious months, Rankine and Mackenzie find themselves at the centre of British pop.

Stand & Deliver

They’d met in the mid-70s. Rankine dazzled by the singer performing with cod-funk act Stand And Deliver at Tiffany’s Ballroom in Edinburgh.

“I just had to get with that voice,” he says now. The 18-year-old multi-instrumentalist lured Mackenzie away for his own band Caspian.

“At a rehearsal I noticed a forlorn look in Bill’s eyes, as if he was saying, ‘Help me, help me.’ I invited him to live at my girlfriend’s flat in Linlithgow and we were off and running.”

Gigging under various monikers (Mike Lawrence Quintet, Mental Torture), the pair’s emerging songbook tapped into an idiosyncratic reservoir of influences; big 60s emotions and orchestrations like Burt Bacharach, film composers, Kraftwerk and the sounds of Black America.

Both loved art-glam (Bowie, Roxy, Sparks), covering Boys Keep Swinging for The Associates’ debut single, reflected in Mackenzie’s operatically jittery, stylised vocals. But the singer, raised on Dusty, Tom Jones, and jazzy torch singers like Billie Holiday, also had a searing soulful depth.

The Outsiders

Punk sharpened their edges, particularly Rankine’s guitars and image. Minus long hair and Afghan coat, he became a photogenic match – part Jean-Jacques Burnel, part old Hollywood idol – for the doe-eyed Mackenzie.

Despite Scotland’s post-punk explosion that spawned Simple Minds, Scars, Orange Juice and Altered Images, The Associates were loners. “We always felt like outsiders, we didn’t fit in anywhere, we didn’t really want to. That whole ‘sound of young Scotland’, that wasn’t us. We moved down to London,” reflects Rankine.

Signed to Chris Parry’s Fiction label, The Associates were joined by Michael Dempsey on bass (mostly live), a founding member of labelmates, The Cure: “They came down to my parent’s house. I was hugely impressed by both Billy’s singing and their deceptively simple songs in a complex setting, both familiar and highly original.”

Australian drummer John Murphy, found via publicist Chris Carr, completed the rhythm section. Dempsey believes Murphy’s “wild, rolling energy” is an oft-overlooked, original contribution to The Associates’ sound (the Eraserhead-haired, punk-loving Murphy had been banging a kit since he was four).

Dynamic Duo

Both Dempsey and Murphy were absent from debut album The Affectionate Punch, co-produced by Mike Hedges, who’d also been instantly impressed.

“They were extremely dynamic as a duo, very exciting to watch live, hyperactive, hyper-creative,” he says now. “Billy was a genius, so was Alan.” Rankine may have loathed the prog-related term ‘virtuoso’, but he was one. Hedges agrees: “He could play a piano stool and make it sound good.”

Hedges had worked with The Cure and cut his teeth with Heatwave and Evita. He had not only, what Dempsey calls, “a good solid engineering background” but also “a mad, zany streak which appealed to us,” Rankine adds. This willingness to experiment – he once tried to record drums underwater – would make him perfect for The Associates.

After The Affectionate Punch’s August 1980 release, the band dropped the definitive article and The Cure-favouring Fiction. Parry retained publishing and paid their rent for months upfront, from September 1980 onwards at a flat in St John’s Wood (damage done by a leaking fish tank would see them ejected from the 52 Carlton Hill residence).

1981, the “year of singles”, Mackenzie declared, came with a sequence of Associates 45s, issued on independent Situation Two. Operating largely as a duo, they retreated into the studio. April’s Tell Me Easter’s On Friday and July’s Q Quarters were recorded with Flood (Depeche Mode/U2) for just £100 at Morgan Studios.

Despite the low budget, both were experimental and cinematic, especially Q Quarters with its John Barry-style drama, full of eerie echoes, coughs and footsteps as if it came from The Third Man’s sewers.

“Vicious Surge Of A Song”

Nocturnal sessions – 9pm Sunday to 9am Monday – led to chemical excess. “We succumbed to the Columbian marching powder,“ Rankine says.

“At 4am you hit a wall. We had Rick Wakeman banging on the door trying to get into his Monday morning session.” Previously they’d just popped pills, dexys and blues, now a bad night with seven grams of speed landed the pair in hospital for four days, strapped up to heart monitors opposite one another.

By August’s Kitchen Person (“a vicious surge of a song,” marvelled Melody Maker at their Single Of The Week), they were back with Hedges at his new facility, Playground Studios, with more time and money. The sonic adventures revved up; Mackenzie sang down a vacuum cleaner, a juddering electric typewriter adding to the rhythm.

“It’s an assault on the senses,” says Hedges. “We’d heard Tiger Feet was one of the loudest singles ever, we wanted an even louder cut.”

Drum-powered electro-funk followed with October’s Message Oblique Speech, while November’s White Car In Germany tapped into 1981’s synth-pop boom on its own terms. Magisterial Euro-decadence came drenched in reverb and surprises, seamless leaps from G-minor to G-major, flapping hardboard and Mackenzie singing through greaseproof paper and a comb.

Throughout these singles – choice cuts compiled on the wonderful Fourth Drawer Down – instruments defy easy identification to psychedelic effect. Too disorienting sadly even for 1981’s record buyers. As turntables span to Vienna, Sound Of The Crowd and Tainted Love, Mackenzie lamented that “ours got peeled off halfway through. That would soon change.”

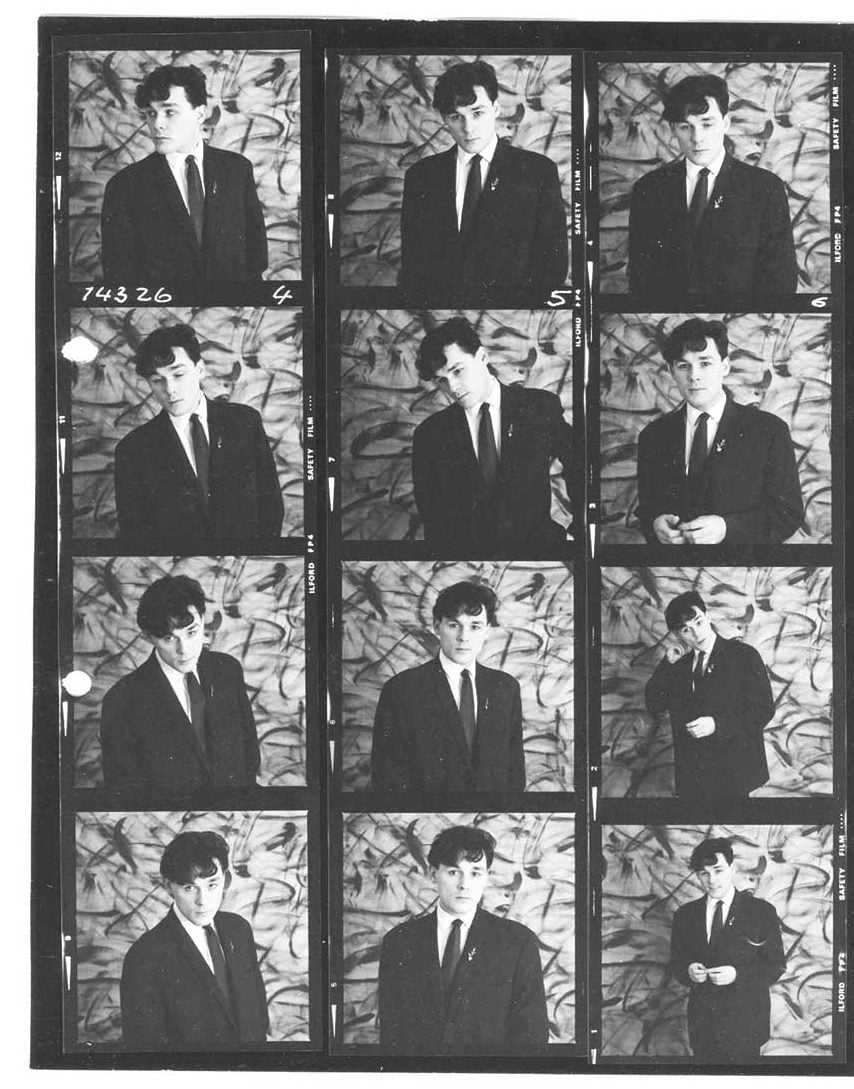

Alan Rankine

Grand Designs

Amid the Situation Two Playground sessions, Sulk’s began. Conceived as a grand design, Rankine likened it to “this luxury embroidery thread in my mother’s sewing box. We wanted to luxuriate in the sounds.” Mackenzie’s vision was similarly vivid: “ABBA meets Bet Lynch on acid” (translation: psychedelic, glamorous, working class pop).

Chunks of Sulk, No, Nude Spoons and It’s Better This Way were in their 1980 live repertoire – instrumental opener Arrogance Gave Him Up had been their concert curtain-raiser. In the studio, these already-written songs mutated with layers of experimentation.

Party Fears Two and Club Country, demoed earlier at Morgan, secured Associates a lucrative deal with Beggars Banquet via Warner (independence, plus major label muscle, the perfect early 80s pop equation). Rankine and Mackenzie immediately signed over half of the £60,000 advance to Hedges.

“We block-booked the studio so if we wanted a day or even week off, other acts could sublet it,” says Rankine, who remembers returning to find The Cure had left a mountain of empty beer cans.

Located on Camden’s Bayham Street, Playground was aptly titled. “I was given the opportunity to build my own studio,“ Hedges says. “I ordered everything that was my favourite, such as a Harrison console – ABBA and Michael Jackson used those. We had two 24-track multi-tracks, one modified into an echo machine. We had delays, phasers, flangers. There were EMT echo plates, digital reverb and Vocoders… It was an engineer’s dream. All the best, brand new gear.”

Fizzing Funhouse

If the world outside was grim (Rankine remembers seeing teens in the alley outside sniffing glue: “they looked like their faces were melting”), inside was a funhouse.

Sounds were layered atop click tracks, with drums overdubbed later. Conventional rock’n’roll was out, so John Murphy’s tom-toms were replaced by snares, giving Sulk a fizzing rhythmic pop throughout. Drums aside, and Mackenzie’s occasional one-string guitar, Rankine played most of the instruments – an ever-present Dempsey is only on Skipping.

“Everything was set up so if I had inspiration for a sound I could just go to a synth or my guitar with its Marshall stacks and Roland Space Echo. The main synths I used were the Roland Jupiter-8, Prophet 5 and a lot of Synclavier. Those cutting, sharp strings on Club Country’s intro, that’s Synclavier. I think we used Solinas elsewhere, too, for those, obviously not real strings.” Sulk’s electronics came without sequencer assistance, adding, Dempsey says, to “its tight, yet human feel.”

Club Country single

Baroque Pop

Songs were magically transformed. No became embossed with what Rankine calls “sort of Russian-Jewish folk melodies” from his piano, and Mackenzie’s vocal embroidery, bellowing through Hedges’ “hall of mirrors” echo. On one take the singer blew an expensive Neumann mic. For the intro, Hedges says they “got a flanger with the hum of a guitar amp going through it, the rest is a bunch of steel parcel banding… or a measuring tape!”

With this supersized nod to the windswept start of Simon Dupree And The Big Sound’s 1967 single Kites (an Associates favourite), its dark electronics and Bond-like cine-drama, No was just one of Sulk’s multi-tiered soundscapes. Party Fears Two’s Yamaha Grand-played piano motif, was captured, Hedges says, “With a Roland SM58 microphone, the top screwed off and laid on the soundbar, lid closed, top covered, running into an amp, flat out with full chorus.”

Elsewhere, a jangle piano tinkles harpsichord-like under Mackenzie’s booming vocal. Evocative of 60s baroque pop like The Zombies, while Party Fears Two’s celestial, synthetic intro puts it right on 80s pop’s cutting edge.

Equally bang up to date were Club Country’s doof-doofs, made by an electronic Simmons kit, all over ABC’s records that year. Contributing to the superhuman radio-ready sound were guitars recorded half-speed, as electrifying played back at normal speed as the oscillator flange behind Mackenzie on the chorus.

“Firing On All Cylinders”

Record label intervention was minimal. When Tarquin Gotch visited, the powder first offered to the A&R man by Rankine and Mackenzie was for anti-indigestion, not cocaine: “We eventually gave him the real thing,” says Rankine. Tales of excess surround Sulk’s making, including blowing up balloons and condoms with helium. “We were getting a bit manic,” laughs Rankine.

However drug-induced the sometimes 16-hour sessions were, all recall them as creative and tightly focused: “We were firing on all cylinders, going at the speed of light,” Rankine reflects.

“It was serious work. Billy was a hard taskmaster,” says Hedges, who was issued with eccentric instructions by Mackenzie to make the sound “like grass, Egypt or coming from inside a sarcophagus.” But the vocalist was mesmerising, too, Rankine recalling him excitedly ad-libbing Skipping’s melodies and lyrics. His words were just as cliché-free and fearless as his daredevil vocal chords.

“Bill was fanatical about avoiding any well-trodden path,” Dempsey says, hence Skipping’s beguiling poetry. Party Fears Two’s jaw-dropping climax was another vocal highlight, the singer revelling in his voice’s elasticity, like a human synthesizer. “As he sang, he’d be hearing himself through all the flangers, reverbs and delays,“ says Hedges. “The effects were part of the performance, not added later. Billy and Alan were very spontaneous.”

Besides sharing an absurd sense of humour, the duo had an almost telepathic bond. “They knew exactly what they were doing. Making Gloomy Sunday, it took minutes for Billy to alight on a setting for this Billie Holiday cover, and an equal time for Alan to organise and communicate it,” Dempsey says, turning the 1930s Hungarian suicide song into an unlikely floorfiller.

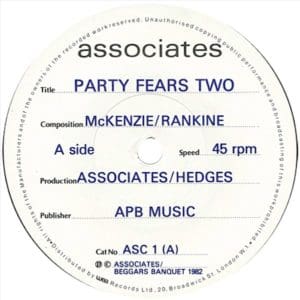

Party Fears Two

Nervous Tension

Nevertheless Sulk was exhausting, after the final mix at Camden’s Roundhouse Studios, Rankine burst into tears – “I wasn’t sad, it was a release of nervous tension.”

They’d torn through Warner’s advance, holed up at Swiss Cottage’s Holiday Inn with Dempsey in one room and Mackenzie’s beloved, room service-feasting whippets in another. Consuming cocaine and cashmere, they even had two cars, a Mercedes 1963 Convertible and cumbersome Ford Dorchester, both driven by Dempsey.

Luckily success soon came with the pop star-style spending. Sulk’s first single, Party Fears Two, was released early in 1982. Radio play was heavy and the reviews ecstatic: “A big, big song with a big, big voice… deserves to be a big, big hit,” said Smash Hits’ new scribe Neil Tennant.

Apparently taking its title from two girls that Mackenzie’s brother saw gatecrashing a party in Dundee, hurling stilettos at a door, Party Fears Two’s immediacy came shrouded in mystery. Euphoria and melancholy collide, the fractured words could be a self-portrait in a cracked mirror. After that final take-off (pop’s most transcendental moment?), Mackenzie sings the opening lines to himself, as if the ravishing, filmic pop song had been a dream.

Top Of The Pops

Top Of The Pops beckoned, as it climbed the charts. Associates’ performances that year are now legendary, but the show’s long hours and early starts were “boring” for Rankine and “a disappointment” for Dempsey.

Ex-Martha And The Muffins’ Martha Ladly, then dating sleeve designer Peter Saville, had joined, adding occasional backing vocals, live keyboards and Mari Wilson-style televisual appeal. But John Murphy was gone, overheard by Mackenzie on the phone bemoaning the pop band he drummed in, replaced by Steve Goulding.

High-profile viewers had tuned in to see Associates on TOTP. One was Martyn Ware, whose British Electric Foundation featured Mackenzie on show-stopping covers, It’s Over and The Secret Life Of Arabia. Another was Bryan Ferry who borrowed Dempsey, Ladly and Goulding for European TV promotion of Roxy Music’s Avalon.

An Explosion Of Colour

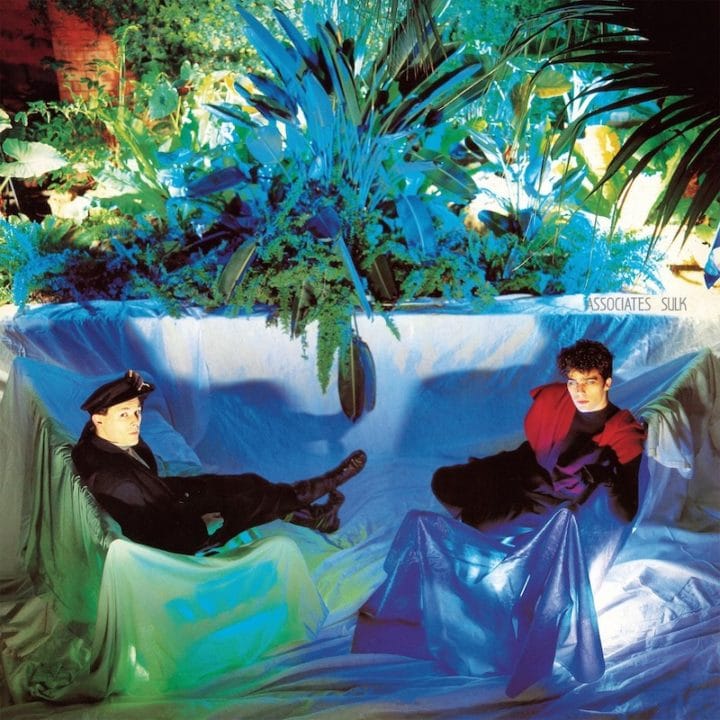

The buzz intensified with Sulk’s May release. The title dripped with phonetic associations, contracting sultry and silk. “It just seemed to fit,” says Rankine, just like the striking Peter Ashworth-shot cover.

“The first sleeve I was captivated by was Hendrix’s Smash Hits. It brought exotica into the family living room,” explains the photographer. You could say the same for his Sulk sleeve, shot in 1982 in a conservatory “somewhere in South London”, on colour transparency with a Hasselblad camera using a 60mm medium wide lens.

Ashworth calls it “an explosion of colour” just like the thread in mother Rankine’s sewing box that inspired Sulk’s sound. Yuccas, ferns and ivy (“weird plants to 80s holidaymakers,” says Ashworth) are lit by 10 blue and green gels glowing under dust sheets covering park benches and “ugly” brick walls. Amid the lava lamp-like setting the duo sit, looking, Ashworth reckons, “a bit like bouncers“, simultaneously safeguarding and luring you into their wonder-house. Full of mixed messages; ultra-pop glamour and anti-pop mingle, the pair’s slightly bored, bemused poses predate Pet Shop Boys. Rankine’s two huge Scott Crolla cashmere scarves and his “otherworldly”-style pose, deliberately disrupted with his half-closed eyes.

For Ashworth the contrast is key. “They brought something unexpected to it,” he says, chiefly the rebel punk that streaked through early 80s pop. “Record companies treated sleeves as throwaway. I was always getting grief for shooting with exotic colours, here and with Dave Ball’s In Strict Tempo. But I was blown away when I saw it, the image bleeding to the edges, the title almost hidden. Did everything a cover should – informed, misled, teased, entertained.” Now hanging in the National Portrait Gallery, Sulk’s cover elevated the form into art, just like the record inside did with pop.

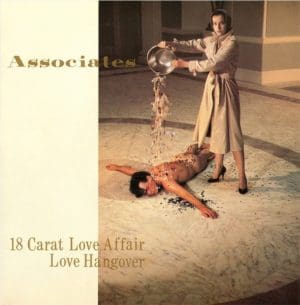

18 Carat Love Affair single

Sensuous Masterpiece

Inside was everything they had been working towards – a dense, swirling, sensuous masterpiece. Arrogance Gave Him Up opened Sulk the way Speed Of Life had Bowie’s Low. Throughout Sulk’s textural overload and crackling invention, Spector-ian walls of sound meet the electronic 80s.

Side A’s assault course of forward-thinking torch songs and post-punk freak-outs (the barmy Bap De La Bap and Nude Spoons sadly missing from the US tracklisting), and Side B’s ultra-pop masterclass. The music press went into justifiable hyperbolic overdrive about the ‘supernatural’ Associates and Sulk’s “timeless majesty”.

Melody Maker’s Album Of The Year came sandwiched between Dare and The Lexicon Of Love, when pop’s possibilities were ever-expanding, when the Top 10 could be occupied by O Superman, Ghosts or Being Boiled. Lush like ABC, soaring like New Gold Dream, and experimental like The Dreaming (and Hedges’ next project, A Kiss In The Dreamhouse), Sulk was really unlike anything before or since.

The best early 80s pop seized on everything the era offered stylistically and technologically while remaining sceptical of its values. Sulk’s second single, Club Country, written, Rankine says, during June and July of 1980, eviscerated the New Romantics’ supposedly hollow nightlife and vacuous style.

Bona Fide Pop Stars

“We went to Billy’s, Blitz, Le Beat Route. I was always bored within 10 minutes, it felt so snobby,” reflects Rankine. Predating Blue Monday by almost a year with its modern dance moves – it’s widely cited as proto-house – Club Country made No.13. But Rankine sensed a change in Mackenzie during their second TOTP performance… “Nothing I could put my finger on…” he says. “something was up.”

Like Party Fears Two, amid Club Country’s ecstatic, athletic rush were lyrical warning signs, flickering like a distress flare: “Every breath you breathe belongs to someone there.” Blitz kid bashing when they were written perhaps but now Associates were bona fide pop stars, they took on a whole new meaning.

Behind Mackenzie’s flamboyant rascal demeanour, the tomfoolery and cryptic lyrics was a hyper-sensitive soul, with fame bringing unwanted attention. Returning home to Dundee had made him a target for abuse. Not that Mackenzie wasn’t tough. While staying at rock star haunt, London’s Columbia Hotel, Rankine remembers him pulverising a group bullying Marc Almond. “He decked them all in seconds.”

Love Hangover

1982’s third single, 18 Carat Love Affair, was their frothiest confection yet (an instrumental mix of its synth-driven 60s-inflected pop, titled Nothinginsomethingparticular, closed Sulk). Composed in 1978, “It’s a gay love song, Bill told me,” Rankine says.

“I knew Bill was gay the first time I met him, 90 per cent gay or already LGBTQ+.” He adds: “actually Bill would shag moving hair on a barber’s floor.”

The single’s other side, an orgasmic reworking of Love Hangover, contained Rankine’s favourite Mackenzie vocal: “It wasn’t his song so he felt removed from it. He had so much fun recording it.”

18 Carat Love Affair’s August Top Of The Pops performance came with two Harrods-made chocolate Jaguar guitars, bringing one for backup in case the other melted under the lights. After handing the fretboard to Mackenzie, Rankine fed the remains to the audience. They clashed with producer Michael Hurll: “I think he was mad that he hadn’t thought of the guitars! We also glued Dave Lee Travis’ dressing room doors together – he’d slagged us off on the radio,” says Rankine.

Bafflingly, 18 Carat Love Affair stalled at No.21. “Billy was very upset about that,” says Hedges. But Mackenzie’s ambivalence towards success rose to the surface. In Smash Hits’ August cover feature, when asked about ambition, Rankine mapped out his future with a clear-eyed vision, though Mackenzie sounded more uncertain.

Read our view of Sulk here

Bono dubbed Billy a disco ball of nerves. And he was. He was also full of contradictions, a showman who hated confronting an audience nightly, a talent of immense diva-style proportions who hated the glare of the media. Being thrust into the limelight exposed the duo’s differences. Rankine accepted the pop machine’s necessary evils, Mackenzie, forever in pursuit of that ‘magical feeling’, found it a disenchanting grind.

“He hated touring. Hated the repetition of miming songs he’d recorded two years ago,” says Rankine. “None of success’ requirements were part of his nature,” Dempsey says. But he was equally afraid of failure. Being sequestered in the studio for Sulk’s making had made the singer comfortable there. The daunting task of recreating it onstage with a ‘messy’ nine-piece band led him to cancel a tour the night before its Edinburgh debut.

Later, Sire’s Seymour Stein would put America and vast sums of cash on the table at Langan’s Brasserie. Mackenzie declined. For Rankine it was the last straw – by October ’82, he’d officially quit. Sessions for a new album at Bahamas’ Compass Point were cancelled.

Mackenzie soldiered on, releasing Ice Cream Factory (with Orbidöig) before the year’s end, when Simon Le Bon named him his favourite male singer of 1982 in Smash Hits. He’d remain a singer’s singer, beloved by all from Jim Kerr and Martin Fry to Siouxsie, Marc Almond and Björk.

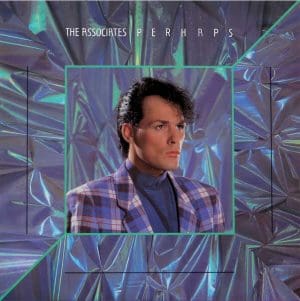

Going Solo

“Most pop stars knew he could sing the pants off them,” says Rankine. Without Alan, Associates were still sporadically brilliant. 1985’s Perhaps featured superlative highlights Those First Impressions and The Stranger In Your Voice. Collaborations with Yello, like Shirley Bassey belter The Rhythm Divine, and 1991’s gorgeous flop single Baby, cannot be dismissed.

But without his alchemist Rankine, records like 1990’s Wild And Lonely were marred by unsympathetic production. Billy was dropped by Warner after The Glamour Chase, unreleased until 2002.

“Fifty per cent of what makes those records great is down to Alan,” says Ware, who worked on Perhaps. “I don’t think Billy realised how hard it would be without him.” Play the Rankine-assisted Peel session of Waiting For The Loveboat and you can hear what’s missing from the (still fine) eventual release, something odder, funkier, sexier. The former’s one of many treasures lurking on Sulk’s three-disc 40th anniversary deluxe edition, along with demos, B-sides and other radio sessions.

After leaving, Rankine went solo (The World Begins To Look Her Age) and produced (Cocteau Twins, Paul Haig). But both men seemed adrift without one another, each missing the other half of their musical whole. “We went too far, too fast,” said Mackenzie in 1985, vowing he’d work with Rankine again (a Spring 1993 reunion was short-lived). “Maintaining the kind of creative energy they had together can be destructive,” says Hedges.

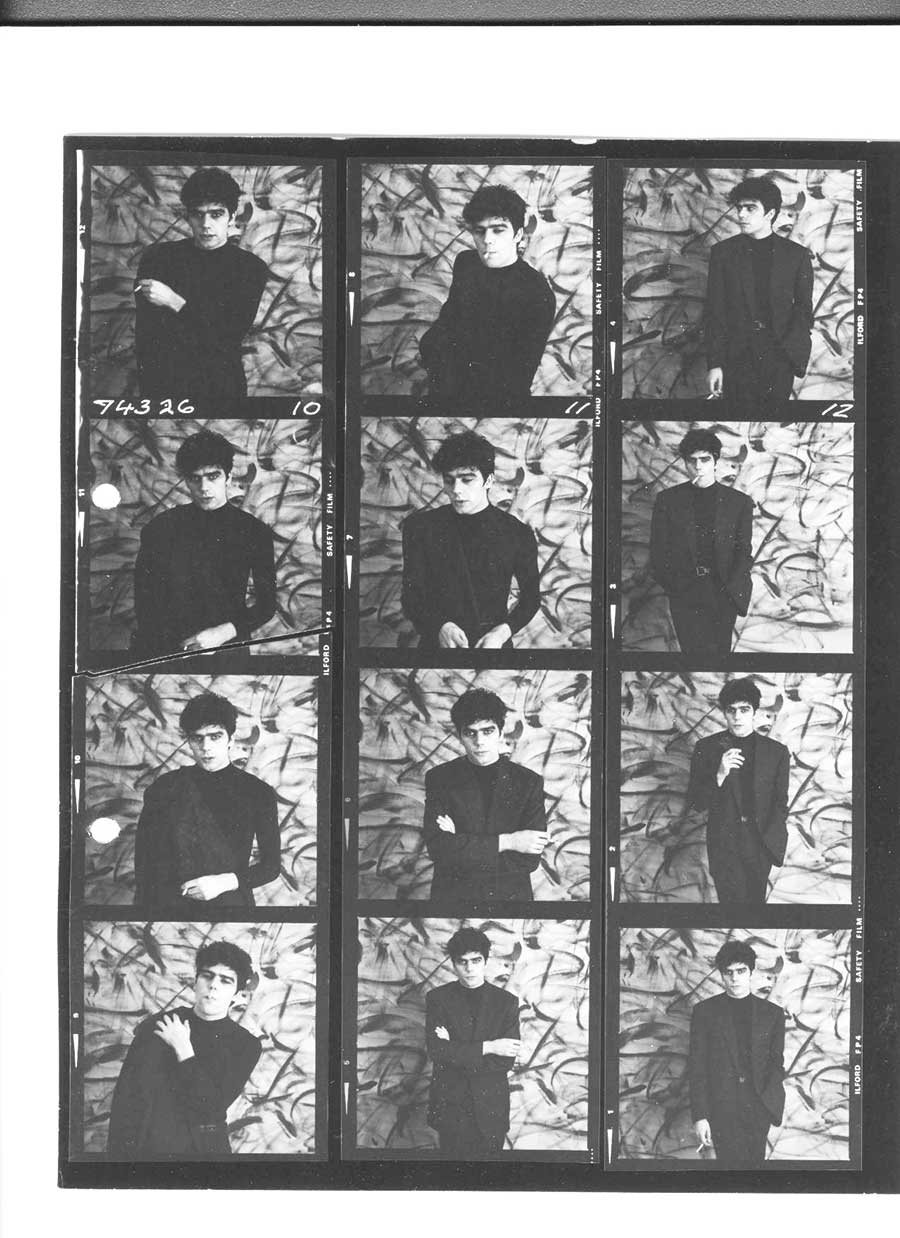

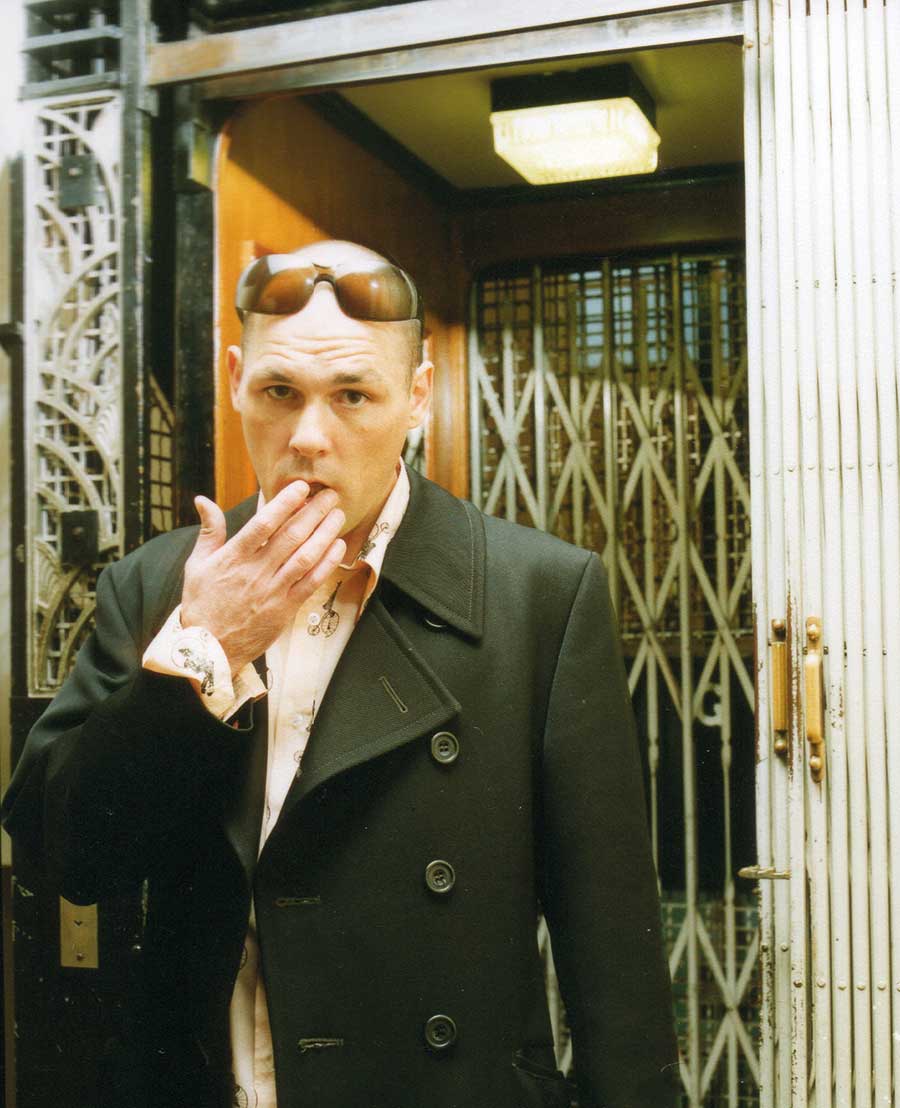

Billy Mackenzie Photo by Mark Guthrie

“Too Far, Too Fast”

Both Rankine and Dempsey now see Sulk as a flawed masterpiece; Hedges says: “Billy would hate me saying this but Sulk is music becoming an art form; something in the anarchy, chaos, the strange sounds, is taking it to another level.” Musicians singing its praises include U2 and the Manics. “Associates were massively influential,” reflects Ware.

Sulk is not just reflective of a wild and glorious time in pop music but an enduring example of what it can be in the hands of visionaries, going “too far, too fast” and over the top without label interference. Right now, current pop needs a few lessons from Sulk.

Just before Mackenzie’s suicide, Hedges says he’d met him with plans to make an album. His final flourish with Apollo 440, 1997’s Pain In Any Language, showed his mercurial genius had not faded, even if the will to live had.

Old friends penned elegies, Siouxsie on The Creatures’ Say and The Cure’s heartbreaking Cut Here. It’s perhaps unwise to view him through the prism of personal, private tragedy. Think of him this way: in a London studio in 1981, Rankine not far away, voice soaring skywards as Party Fears Two reaches that heavenly ascension.

Read More: Top 40 80s pop artists

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.