Between 1998’s solo album and his death in 2019, Talk Talk singer Mark Hollis retreated into a reclusive, enigmatic silence. Aided by a new book and a documentary, we explore the story behind the sunglasses…

Between 1998’s solo album and his death in 2019, Talk Talk singer Mark Hollis retreated into a reclusive, enigmatic silence. Aided by a new book and a documentary, we explore the story behind the sunglasses…

When Talk Talk mastermind Mark Hollis died, aged 64, in 2019, the outpouring of grief was so great that, while it didn’t match the mourning provoked by Davie Bowie’s or Prince’s passing in 2016, it nonetheless came close.

Dismissed early on as lightweights, Talk Talk and Hollis had come to be recognised as among the most influential acts to emerge from their era, with initial pop nous admired by the likes of No Doubt, who had a huge hit with a cover of It’s My Life in 2003, and later, sophisticated work championed by Elbow’s Guy Garvey, Underworld’s Karl Hyde, Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon and Robert Plant.

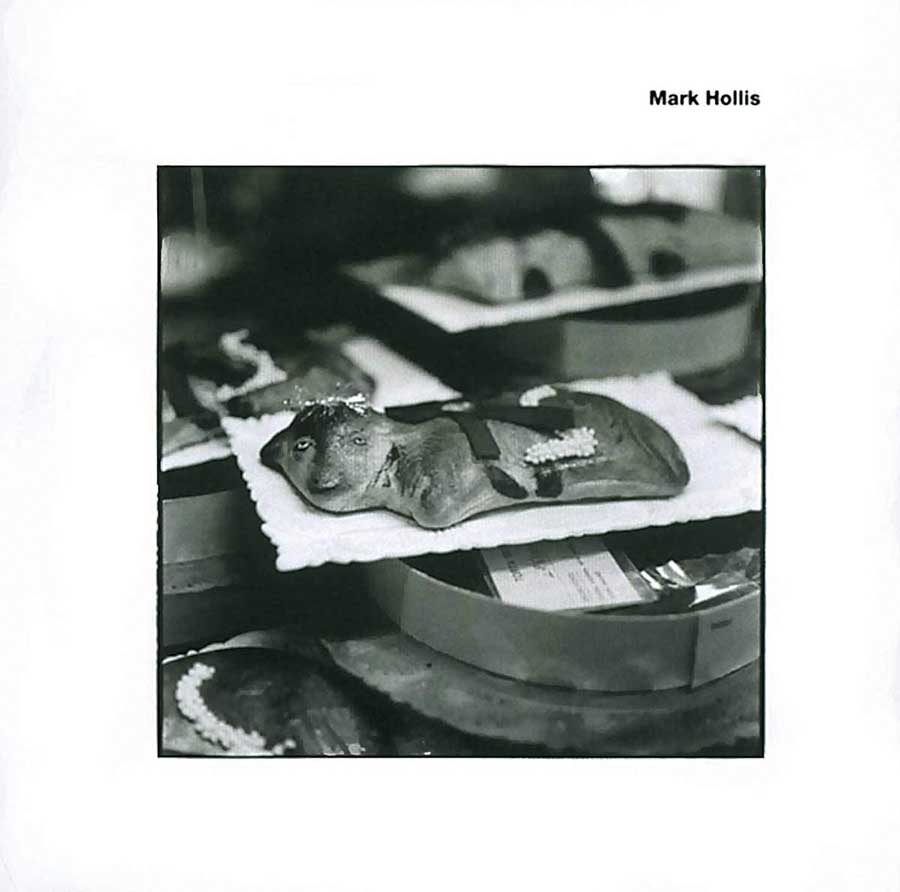

That people could feel so bereft was, to some, unexpected. It’s now more than 30 years since Talk Talk’s final album, 1991’s Laughing Stock, and next year it will be a quarter of a century since 1998’s Mark Hollis, his lone solo LP, while none of his recordings has grazed a Top 40 chart since 1990’s Natural History: The Very Best Of Talk Talk.

Furthermore, aside from a handful of collaborations – the last in 2001 on Norwegian-Polish singer-songwriter Anja Garbarek’s beguiling Smiling & Waving – Hollis’ only music since 1998 is less than a minute long: a quasi-baroque instrumental, ARB Section 1, from a 2012 episode of Kelsey Grammar’s poorly performing TV show, Boss. Beyond that, he maintained a watertight public silence. One could be excused for not knowing who Hollis was.

If the fact he’d not been largely forgotten was surprising, fans discovering their passion was widely shared enjoyed a bigger revelation. There were, doubtless, countless people who still loved his band’s first two, often maudlin synth-pop albums, 1982’s The Party’s Over and 1984’s It’s My Life – home to hits like Today, It’s My Life, Such A Shame and Dum Dum Girl – not to mention 1986’s more analogue The Colour Of Spring, which delivered even more classics like Life’s What You Make It and Living In Another World.

But 1988’s Spirit Of Eden, as well as the similarly commercially ill-fated Laughing Stock and Mark Hollis, appeared most lauded, and these, in contrast, are best heard with the lights down, when the beauty, comfort and redemption they offer are most affecting. More importantly, one listens to them alone, making this a private, even intimate relationship. In the wake of Hollis’ passing, it appeared there was an entire community of like-minded souls whose lives they had touched in an uncommonly profound manner. Suddenly, it transpired we’d never been alone at all.

In the silence Hollis left behind, devotion to his achievements has grown. He gave his last interviews around his eponymous album, and Paul ‘Rustin Man’ Webb (bass), Lee Harris (drums) and Tim Friese-Greene (sometime producer and multi-disciplined, unofficial Talk Talk band member) have also refused to discuss their work together ever since, apparently out of respect.

“I would rather just have the album say what it is itself and not do anything for it,” Hollis told International Musician And Recording World’s Andrew Smith on the eve of Spirit Of Eden’s release. Ten years later he extended his fondness for reticence further, telling Danish TV: “I get on great with silence. I don’t have a problem with it. It’s just silent, y’know. So it’s kind of like, well, if you’re going to break into it, just try and have a reason for doing it.”

This was a practice at first applied only, albeit increasingly, to his songs. Nevertheless, it reflected later life choices, and his closest collaborators adopted it, too. As Martin Ditcham, who worked on and off with Hollis from The Colour Of Spring until the solo LP, reiterates, “Mark would certainly have endorsed that now hackneyed expression, ‘Let the music speak for itself’.”

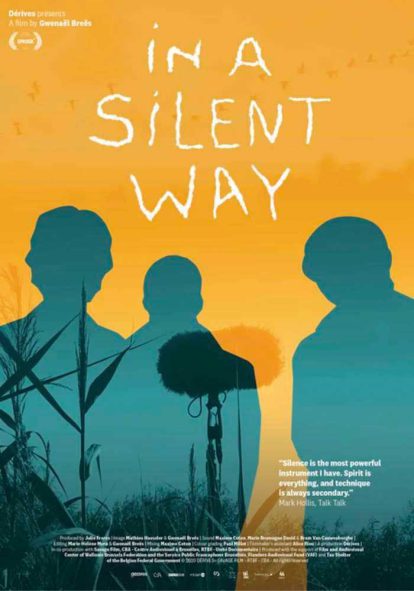

But if studio engineer Phill Brown, who worked on Hollis’ last three albums, politely considers his refusal to talk as “a ‘fuck you’ to the fans”, an opinion expressed in Gwenaël Breës’ Talk Talk documentary In A Silent Way, the tactic has worked. Even Ditcham confesses of Spirit Of Eden: “It certainly didn’t excite me on first listening. I thought it was so marginal, so exceptional and so inaccessible that, although I eventually grew to love it, I was astonished it got released.”

And yet the less Hollis said, the more his disciples fantasised, with a subsequently enviable word of mouth campaign helping him reach an audience far greater than those records’ immediate reception could have anticipated.

For over two decades, fans have speculated about the manifold inconsistencies at the heart of Hollis’ catalogue, and an almost unprecedented, unrivalled mythology has flourished, with chart-friendly years seemingly incompatible with the complex, commercially doomed style with which he quietly bowed out. So why did a band considered pretenders to Duran Duran’s throne end up spurning the spotlight?

What led Hollis to reject fame in favour of music so esoteric and fastidious? And is Creation Records founder Alan McGee’s claim that Hollis’ is a “story of one man against the system in a bid to maintain creative control” accurate, or is his actually a tale of artistic indulgence, summarised in unusually candid fashion by former manager Keith Aspden’s remark in 2011 that “Mark had his cake and ate it all himself”? It’s unlikely we’ll ever know. Like Ditcham says: “Unanswered mysteries always have legs!”

Few artists succeed in making such sharp left turns – from articulate, refined pop to something almost metaphysical – so it makes sense people want to know more. Fortunately, this Spring brings two contrasting attempts to unravel such mysteries.

Ben Wardle’s Mark Hollis: A Perfect Silence is the first full-length biography about the reclusive figure, while Breës’ aforementioned documentary explores the Belgian director’s relationship with Hollis’ records – he calls later ones “life companions” – as well as their making.

Perhaps inevitably, both provoke as many questions as they offer answers, and it’s notable their apt titles come in part from what appears to have been Hollis’ central creed, expressed – yet again – in an interview with John Pidgeon around Laughing Stock: “I would rather hear one note than I would two, and I would rather hear silence than I would one note.”

Talking to Wardle, it’s clear that resolving the contradictions of Hollis’ life was quite a task. “Don’t get me started,” he laughs, before summing them up succinctly. “Hollis was an acetic, loner genius who loved pubs, swearing, fast cars and golf. The number of times I had to think of synonyms for ‘dichotomy’!”

Breës, meanwhile, faced an even greater challenge. “Hollis heard about my project before I even contacted him,” he explains. “I received a letter from his lawyer firmly forbidding me to use his music and asking me to abandon my project.

“I then wrote to Hollis personally so that he would understand what was driving me, that I was interested in the music, the approach, the spirit, not in his personality or his private life, not in making a biopic. He replied very kindly, but asked me to respect his position: ‘I would be wholly against a film being made in connection to these albums, since I prefer that they be allowed to stand alone and exist in their own right.’”

Fans need not despair. Without compromising Hollis’ wishes, Wardle and Breës have trawled the archives and tracked down other collaborators and associates, shedding light on how this music came into existence as well as the personalities behind it. Moreover, despite Hollis’ convictions, our understanding of his recordings and performances is only enhanced by details of its provenance, and their magic is powerful enough to resist distractions.

The picture which emerges is, admittedly, occasionally uncomfortable, but the truth was always in plain sight if only the myths had cleared. “Having worked with a number of artists in my former life as an A&R person,” Wardle pithily points out, “my experience is that most of them have teeth when it comes to their music. You simply don’t sustain a career by being nice to everyone. Unless you’re Dave Grohl, anyway.”

Talk Talk – and, in particular, Hollis – were always enigmatic figures, not least for what Depeche Mode’s Alan Wilder once called “a career in reverse”, with the distinct schism between the band’s first hit albums and final neglected two bridged by The Colour Of Spring’s international accomplishments.

As Wardle writes: “To German, Italian, Spanish or Dutch fiftysomething music fans, [Hollis] is an 80s superstar – a Boy George or a George Michael; to younger musicians, journalists and music obsessives all over the world, he is a visionary akin to Scott Walker, Nick Drake or Syd Barrett.”

No wonder, really. Hollis was schooled as a 70s youth in an extraordinary range of music by his erudite brother, Ed – manager of Canvey Island pub-rockers Eddie & The Hot Rods – and his recordings with his first band, The Reaction, also managed by Hollis Sr, reveal a man well versed in punk and new wave.

An early Mirror Man – later reworked for The Party’s Over – boasts a reggae feel worthy of The Police, I Can’t Resist sounds almost like Elvis Costello, while Talk Talk Talk Talk, later reinvented as his band’s signature tune, could pass for Dr Feelgood.

Still, after Hollis had met keyboardist Simon Brenner, Webb and Harris – the latter two joining from ska band Eskalator, who’d caught Ed’s ear while he produced their demo – Talk Talk launched themselves in spotless white suits with songs that arguably sat comfortably under the New Romantic banner.

Hollis, however, further muddied the water by punctuating interviews with seemingly bizarre references to King Crimson, John Coltrane, Shostakovich and Debussy, all of whose influence was practically invisible. The press were baffled, sometimes aggressively negative, and Hollis’ attitude didn’t help.

During media engagements he refused questions about his private life and was as likely to be sarcastic as sincere, while he sometimes dismissed innocent if admittedly superficial questions with cryptic, even barbed responses. “Talk Talk,” wrote critic Richard Walmsey in International Musician And Recording World in 1986, “are a remarkable example of the thin borderline between genius and sheer cretinism.”

As for that pivotal third album, Hollis declared it only came about because he had a bigger budget. Previously, he claimed, electronic instruments were employed purely because he couldn’t afford real musicians, but with It’s My Life producer Tim Friese-Greene established as his co-writer and Brenner gone, he now adopted a defiantly organic sound, populated by contributions from the renowned likes of Traffic’s Steve Winwood, The Pretenders’ Robbie McIntosh and Pentangle’s Danny Thompson.

Afterwards, in another confounding display of artistic idiosyncrasy, having secured worldwide hits and wowed audiences with an enviably tight band, Hollis turned his back on performance, making only occasional, awkward promotional appearances.

Instead, he surrendered two years to Wessex Studios, where, with Webb largely sidelined, the uncompromising Spirit Of Eden and then, a couple of years later, Laughing Stock were improvised and recorded. It’s these which are arguably most responsible for the utopian visions of artistic freedom orbiting Hollis.

Meticulously pieced together, commercially doomed but artistically triumphant, Spirit Of Eden alone involved some 50 guest musicians given little guidance nor any opportunity to prepare for their contributions, their work sometimes employed, if at all, in different contexts. “Once we spent five 12-hour days getting a guitar sound,” Brown told me in 2013. “It was an extremely unusual way to work.”

He’s not exaggerating. “In my case, a process of elimination was put into play,” Ditcham recalls. “They wouldn’t let me hear the music. I’d do two or three tracks of various percussive ideas, then later they’d cherry-pick what they liked.”

He also recalls a studio environment inspired by stories Brown had told Hollis about working with Traffic in 1967. “Flashing strobe lights under a semi-transparent bucket,” he lists, “and cheap, flashing disco lights in front of Lee’s drums. In the control room all the lights were off except for a 60s rotating projector loaded with an oil-filled slide shining colourful, slowly evolving, psychedelic patterns. It was certainly a very mysterious atmosphere.”

While Spirit Of Eden was said to be loathed by the label who’d paid for it and largely scorned by critics – neither rumour’s entirely true, but legends are always popular – Hollis and his associates would do it all again, having jumped ship from EMI to Polydor after a protracted court case, for Laughing Stock.

“I know the album feels like seven guys playing live in a room, but every note is ‘placed’ where it is,” Brown told me, recalling Hollis’ quest for perfection. “The album is an illusion!” Both it and Spirit Of Eden are, of course, now deemed pinnacles of artistic achievement which put music beyond any other consideration, but it’s not that this came without pain.

“It took its toll on people but gave great results,” Brown continued. “There was divorce, breakdown, it was intense. I have never worked on more focused sessions, though. And no, I would not work in the dark again.”

That Hollis concluded his career with a painstakingly arranged solo album of pseudo-chamber music recorded purely with acoustic instruments – the polar opposite of Talk Talk’s first work – makes sense in the light of this endlessly unpredictable career.

It’s probably Hollis’ ‘difficult’ nature that’s the most consequential aspect of this year’s retrospectives. Hollis, Wardle reminds us, could exercise a distinctly ‘laddish’ character, and his pursuit of his goals sometimes showed little regard for those upon whom he depended for their realisation.

Touring was such a struggle he turned to alcohol and pranks to survive, and Clive Black – now an industry veteran, but then an Island Records junior who helped sign him to a songwriter deal – recalls how INXS’ Garry Gary Beers was once lured into Talk Talk’s dressing room on his way to a festival stage only to be blinded by an eyeful of gin thrown by the band.

In Breës’ documentary, meanwhile, Ian Curnow recalls having his fingers tied together and being forced to play keyboards for hours in considerable discomfort, and it’s clear that, though this indignity is usually cast as ingenious by Hollis’ fans, the memory is far from welcome, and that this fate’s sometimes attributed to Nigel Kennedy instead probably hasn’t helped.

There are, too, more than a few hints of bitterness from those who feel their contributions were undervalued, especially those who believe they were due songwriting cuts – “[Manager] Keith and Mark are both ruthless,” Brown told me – and one can’t help wondering whether the silence around Hollis has roots in people’s determination not to get involved in debates about his demeanour.

For all this, there are plenty of accolades for both his music and personality. “It’s true there were occasions when he could be a bully,” Wardle says. “Lee Harris was repeatedly asked to replay a drum part during the record of Laughing Stock without any explanation as to what he was doing wrong. But there were an equal number of occasions where interviewees told me how lovely Hollis was.

Harmonica player Mark Feltham, guitarist Robbie McIntosh and pianist Laurence Pendrous all recounted in detail how enjoyable his company was.” Ditcham, too, says he “never witnessed any difficult or uncomfortable situations,” adding “his approach certainly got the best out of a musician.”

Wardle also points to Phil Ramacon, whose multiple experiences working with Hollis epitomised its pitfalls and pleasures. “He told me how much he enjoyed his company, how Hollis bought him clothes for their shows and would regularly make him cheese on toast in his flat before they went to rehearsals together. But he also told me how he had helped Hollis assemble and write Such A Shame from fragments of cassette ideas.

“He was refused a publishing credit and ultimately felt he could no longer face playing with Talk Talk because he felt so exploited. That said, he liked Hollis enough to work with him again on the solo album, albeit after having insisted on getting a co-writing credit!”

In the end, the mysteries remain. Hollis willingly disappeared, leaving his music to do the talking, and though we now know a lot more, its mystique remains unblemished. If his methods were occasionally disagreeable – and, let’s be honest, they were – his artistry, not to mention his unforgettable hits, will outlast them.

As Wardle concludes: “Anyone who pursues his own vision against the prevailing wind of opinion and fashion, and creates something which grows in stature as each year passes, is a genius.” That Hollis rests in peace so prematurely is tragic, but peace was always what he sought most. It remains his greatest gift.

Reviews

Mark Hollis: A Perfect Silence by Ben Wardle

Taking us from Hollis’ Tottenham birth and suburban Southend childhood, Wardle begins with his solid family upbringing in post-war Britain, then guides us all the way to the stylish house in which he was living when he passed away, and if his image as a saintly genius is occasionally threatened, at least Wardle’s enthusiasm for Hollis’ music makes it easier to separate art from the artist. Ultimately, the book should satisfy those looking for a historical document as well as those seeking greater insight into his challenging, at times peculiar techniques, and, furthermore, it leaves enough of his inscrutability intact to safeguard Hollis’ ongoing, influential legacy. ★★★★

In A Silent Way (Directed by Gwenaël Breës)

It’s clear from its start that Breës’ debut isn’t going to be a typical documentary. Opening with former associates and allied critics reading a letter from Hollis’ legal team distancing him from the project, In A Silent Way instead becomes an oddly compelling meditation on creativity, what we seek in music, and how we listen to it.

Consciously lo-fi, it sees Breës unstitching some of the myths behind the band’s transformation and transformative recordings, with talking heads ranging from youthful acquaintances like Eddie & The Hot Rods’ singer Barrie Masters, who recalls Hollis’ work as a roadie, to musicians, engineers and even random strangers, including, bizarrely, Frank Bruno’s former sparring partner.

Breës makes pilgrimages to Southend, Canvey Island and Wessex Studios and even considers ringing Hollis’ doorbell, while a group of musicians, adopting Hollis’ techniques, provide an improvised post-rock soundtrack. (Talk Talk would admittedly have been preferable.) Consequently, what starts as a quest for the truth behind some of the greatest records ever made ends up – as so often – bent to Hollis’ will, provoking a less accessible but ultimately more inventive film which ultimately remains in thrall to the power of the enigma. Hollis, one suspects, would have approved. ★★★★

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.