Karl Bartos, 2021. Photo by Patrick Beerhorst

Classically trained musician Karl Bartos was a member of Kraftwerk on a staggering run of albums from Radio-Activity to Electric Café. Having previously stayed silent about his former band, his powerful new autobiography offers a wholly new perspective of life inside the man-machine. He gives his first British interview about Kraftwerk and beyond exclusively to Classic Pop…

While Kraftwerk have justly been lauded for their pioneering adventures in electronic music, it shouldn’t be dismissed just how fantastic they looked, too.

Fixed in many people’s minds as the classic line-up of Ralf Hütter, Karl Bartos, Florian Schneider and Wolfgang Flür on the cover of 1978’s The Man-Machine in red shirts and black ties, Bartos has a brilliant theory on why Kraftwerk could pass themselves off as robots: they were all the same height, a uniform 6ft.

“We were all alike,” notes Karl. “No one was very short, no one was a giant. It never happened, but we could all have exchanged clothes. Everywhere we went, we received a very strong reaction and knew that a certain identity was coming across.”

In his remarkable new autobiography The Sound Of The Machine, Karl describes how he needed to be a musician from the moment he first heard The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night. He feels there was a connection in the two bands’ image.

“It was never ‘John Lennon And The Beatles’ or ‘Paul McCartney And The Beatles’,” Bartos points out. “The Beatles were always ‘The Fab Four’, a proper band. Kraftwerk had that equality, too, in how we looked. We were the perfect band, as we had no one star dominating our appearance. People like that equality.”

It’s a typical perfectly formed theory from a musician who – like his former bandmates – has very rarely spoken about life inside Kraftwerk. Karl is literally better qualified than most to theorise about pop music.

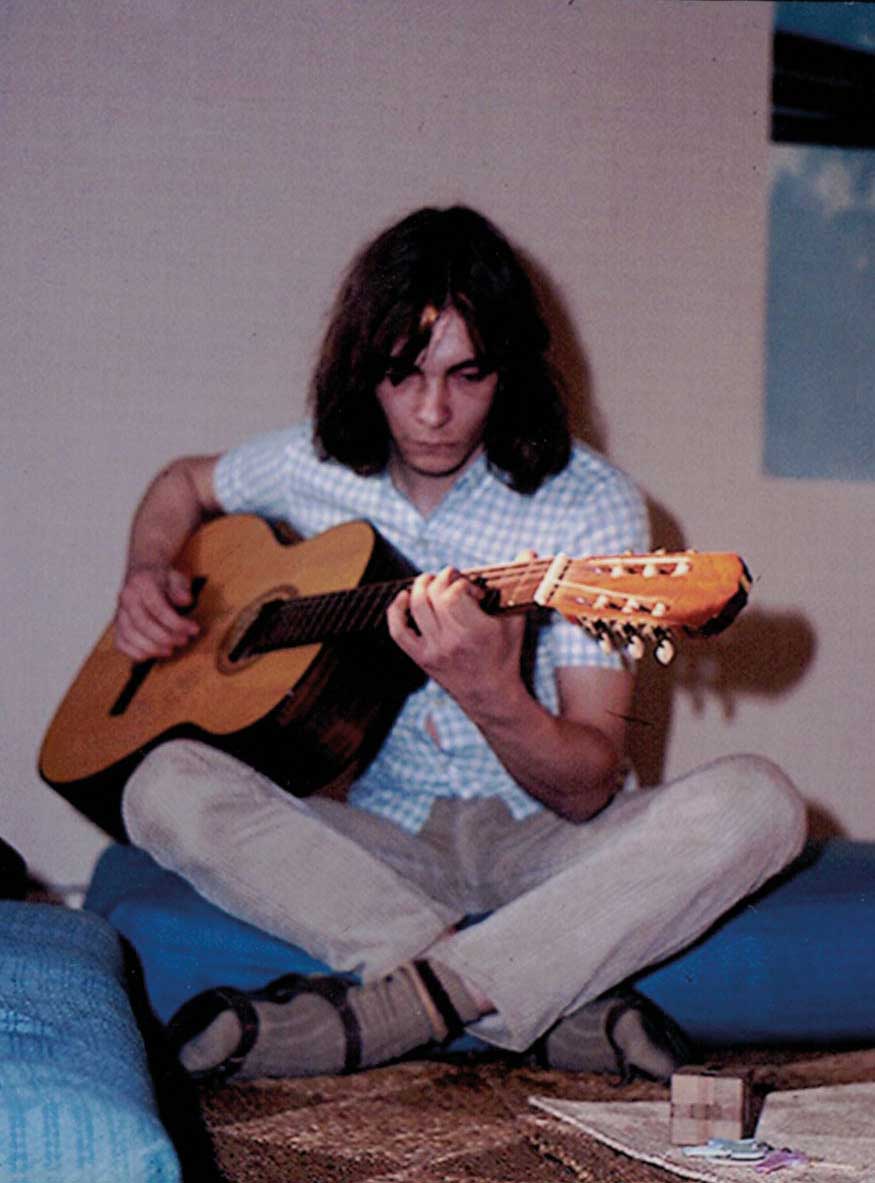

Karl Bartos on acoustic guitar, 1971

He studied percussion at the Rhineland State Conservatory Of Music from 1970, combined much of his time in Kraftwerk with teaching music and, in 2004, he founded a masters program for Berlin’s University Of The Arts, in acoustic communication. Inside the shiny robot of Kraftwerk lore beats the heart of a man who lives for music.

A reticence to discuss his tenure in Kraftwerk – “I’ve always felt uncomfortable talking about our time together” – means Karl’s views on music are barely known. But they really should be. Hearing his insight is a delight.

The mystique that grew up around Kraftwerk in the 70s means they are frozen in time as those robots. In reality, over Zoom from his home in Hamburg, Karl couldn’t be more humane.

His study is far more lecturer than electronic pioneer: a wall of filing cabinets, small pot plant, a planner stuffed with Post-It notes. Bartos, neat silver hair side-parted and cosily dressed in a navy zip-up fleece, is disarmingly friendly.

Kraftwerk clichés and decades of silence mean you might expect icy detachment, not someone alight with mischief and a gentle, ready smile. Karl’s English is near faultless: the only word he struggles with is “ephemeral”, which would even be understandable in native English speakers.

SCIENCE OF SILENCE

Bartos spent three years writing The Sound Of The Machine, including overseeing its conversational English translation. Don’t be put off by the book’s 641-page length: it speeds by, revelatory about the workings of Kraftwerk and lively with theories on the relation between music and nature.

“In a profound way, music imitates life,” Karl offers. “It’s born in silence, unfolds in space and time, then fades away and dies in silence. That’s what people do, too. We probably love music so much because it reflects our life. Music helps me get to the point where I understand what people get from religion and the eternal.”

This isn’t necessarily the sort of passionate discourse you’d expect from the man who helped make Spacelab.

But the human side of Kraftwerk is a major reason why Karl is now ready to discuss his perspective on the band: to explain that talk of robots and electronics need to be completely revisited and instead to realise that this was music made by humans, not machines. Karl is particularly fond of The Man-Machine’s concept, hence the title of his book.

“I like the idea that Fritz Lang had for ‘the man machine’ in Metropolis,” says Karl of the director’s visionary 1927 film. “Kraftwerk took on that idea, of the robot becoming the voice of Metropolis’ lead female character, Maria. ‘Man machine’ is a good expression, because ‘man’ comes first, not ‘machine’.”

It’s the human interaction in Kraftwerk that Bartos remembers most fondly in Kraftwerk, of working at the legendary Kling Klang studios in Düsseldorf.

Asked for his favourite memory of the band, Karl immediately responds: “The writing sessions. We’d play like children, or maybe freeform jazz musicians. Music is all about conversation, and musical conversations are what we created: one instrument talking to another, with the third instrument giving a comment on the conversation.

- Read more: Making Kraftwerk’s Autobahn

“Before starting a song, we’d talk to each other: about music, society, the music business. We’d talk about David Bowie’s ability to be so natural in talking to the music press, which we admired. Then after these conversations, we’d get our instruments and, almost with no effort, restart those conversations in our music.”

They’d then go to dinner, return to the studio and soon head out for what Ralf, Karl and Florian called “the sound drive”, testing their demos in the car.

Computer Love was typical of the way the trio were in harmony in the studio: “I had a piano in the rooms where I taught music,” Karl recalls. “That gave me a chance to improvise. I came up with this melody, wrote it down and brought it into Kling Klang.

Karl Bartos in the studio.

“I played it on Florian’s synthesizer and, with no delay, Ralf changed it to the right chords for Computer Love. I came up with a second melody, Ralf responded with the refrain. And that was it, the song was done in five minutes. I still have that original demo.”

This human interaction is familiar from the pop realm, but a world away from Kraftwerk’s robotic aura. It’s why The Sound Of The Machine needed to be written. Karl explains: “We had equality at the start. Our conversations were at the centre of our music. It was a communal act of creation. It was a good effort, because it felt like no effort.”

But, since Wolfgang Flür left in 1987 and Karl three years later, Bartos feels Ralf Hütter has rewritten the band’s history, without any new music – bar 2003’s confused Tour De France Soundtracks – to give his version of the band any credence.

“We’ve heard the same story about Kraftwerk for more than 40 years,” Karl says. “I wanted to show the other perspective. The main theme of Kraftwerk was the digitalisation of technology – but the music to express that was created by Ralf, Florian and I making music in the normal way, keeping on working in a human approach. By the end of my 16 years in Kraftwerk, that creativity had turned, from a human concept to a very non-human concept.”

ANALOGUE DREAMS

Karl was 22 when he joined Kraftwerk. Like his future bandmates, Bartos had worked with influential producer Conny Plank. He met Ralf and Florian shortly before Autobahn was released in 1974. Karl remembers how Ralf – like Florian, six years Karl’s senior – picked him up from his Conservatory in Ralf’s grey Volkswagen.

“Ralf and Florian were young and artistically involved,” Bartos recalls. “They had no idea about classical music. Like me, they’d grown up in the pop era, when music was the centre of youth culture.” Karl believes his classical training was a fascination to Ralf and Florian.

“It was a culture that Kraftwerk were against,” notes Karl. “It’s funny, because they’re now the same: they both repeat The Magic Flute over and over again.”

The fact that Kraftwerk’s synths were analogue was important. In his book, Bartos writes how “looking at each other, not at computer screens” was vital to their musical communication. “We made music in the analogue era, not its digital substitute,” he reasons.

“Playing on our analogue instruments was like playing with a music box. The music had a romantic feeling, recalling the Romantic era writers like Edgar Allan Poe and E.T.A. Hoffmann.

“There’s something mystical about a music box, like those machines had a soul. The composer Ravel saw a ballerina figurine turning on a music box and said: ‘I can almost hear her heart beating.’ That’s why Kraftwerk’s music is still alive – beyond our music is something people can still feel.”

That romance was the essence of Kraftwerk’s concerts, during which Karl recalls: “I felt waves of happiness and confidence running through my mind. That ensemble worked and it had a quality you simply can’t describe with words.”

Karl believes 1981’s Computer World and its accompanying tour were the final peak for Kraftwerk. “The tour was fantastic,” he smiles. “The feeling within us as a group was wonderful. The current Kraftwerk’s ‘3D tour’, we were already doing that.

“We were us, playing music and looking at each other. I could clap Ralf on the shoulder, give Florian a little hug. We had fun, playing Pocket Calculator then going to a club after the concert. Unfortunately, everything changed.”

Reaching No.1 in Britain in 1982 was a bittersweet moment. “The Model/Computer Love, that was my Day Tripper/We Can Work It Out moment,” notes Bartos. “Getting to No.1 was obviously a good feeling, but it was more of a question than an answer.

“I already had some ideas from the tour, like the riff for Sex Object and the melody for The Telephone Call. We had 20 or 30 ideas like that. But, by the time of our No.1, we had stopped playing, feeling and responding to each other.”

Karl Bartos. Photo by Markus Wustmann

In Karl’s view, there were numerous reasons that Kraftwerk stopped communicating in the studio. In purely musical terms, the world started catching up once synthesizers became more commonplace. “It was important to Ralf and Florian that they were the elite,” Bartos believes.

“Within Kraftwerk, there was always an elite aura about money: boarding school, holidays in St Tropez and St Moritz, shopping in New York.

“At the beginning, that was all funny, but it became a threat. Once the music business caught up with electronic sounds, my ex-partners were overwhelmed by the idea that they were no longer the elite in artistic thinking.”

Rather than find new ways to forge ahead, Kraftwerk instead became caught up with whatever new instruments were in vogue. A bleakly funny passage in The Sound Of The Machine describes Karl’s horror at seeing an unwieldy Synclavier installed in Kling Klang.

“The computer tidies up art,” insists Karl. “In Techno Pop, we used computers and it became music by copy-and-paste. Copy-and-paste cannot replace the idea of composition in the brain, the poetic. You can never reach the level of the poetic by copying and pasting.” The more Ralf and Florian peered at their new computer screens, the more Karl and Wolfgang worried.

A classic example of an overthought album, during the five-year sessions for Techno Pop Kraftwerk tried recording with external producers for the first time, including François Kevorkian and New Order associate Michael Johnson.

“They are fantastic engineers, but they’re not songwriters,” shrugs Karl. “On Techno Pop, we looked too much at our own time and its fashions, its technical innovations, instead of focusing on putting together our very own musical elements. The world beyond time is a much better guide to the act of creation.”

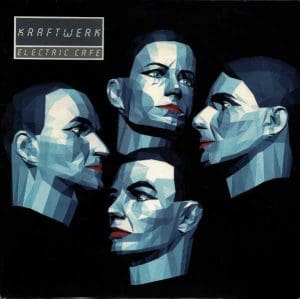

Kraftwerk – Electric Café

When Electric Café, aka Techno Pop, finally arrived in 1986, it flopped. Kraftwerk were suddenly behind the times, not ahead of the curve. To compensate, their record label suggested releasing a Best Of and touring it. “That’s what we should have done,” accepts Karl.

“By touring and putting out an easy Best Of, we could have become personal with each other again.” Instead, they spent five more years polishing up old songs for The Mix. In despair, Bartos quit.

“We should have gone back to the things that brought us together,” he frets. “That’s where our best music came from. I had to go. For 10 years, I’d been asking, ‘Let’s be musicians, let’s play together.’ And it didn’t work.”

LIVE MUSIQUE NON STOP

Of course, Kraftwerk’s live shows continue to routinely receive critical adoration but there’s no new music to accompany them.

“Ralf completely changed into a businessman during the 80s,” frowns Karl. “He always had a business brain. It meant Kraftwerk were more organised than other bands. But Ralf became the only member to do interviews, and the idea came into the public’s mind that Ralf was Kraftwerk. If Ralf is Kraftwerk, where is the new Kraftwerk music? You can’t just replace people like me, Florian and Wolfgang with engineers.

- Read more: Moby interview

“The man machine had changed into becoming the computer machine. Kraftwerk has become a conveyor belt, about manufacturing products from old ideas.”

Karl and his wife Bettina attended a Kraftwerk concert in Hamburg: “We left. It broke my heart, really.” For Bartos, the lack of new music is maddening. “The same idea is multiplied over and over again,” he says. “It’s completely the wrong idea, but Ralf gets away with it.”

Among the musical differences, financial concerns also contributed to Karl’s departure. He nearly left after Trans-Europe Express, before Ralf and Florian agreed to make Bartos a full partner in Kraftwerk’s business dealings.

But once he quit teaching music to become a full-time member in 1981, he realised that Kraftwerk’s opaque writer/producer credits on their sleevenotes made it possible for an unequal financial set-up. Eventually, there was an out of court settlement over Karl’s royalties, though he states: “That agreement seems to be a construction area forever.”

Appearing saddened rather than furious at their differing financial perspectives, Bartos believes: “Our creative process was a communal joy and effort, but the recognition and profit were privatised. That didn’t work in the long run and I wasn’t born to be a yes man.”

Shortly after Florian himself left Kraftwerk in 2008, he and Karl bumped into each other in Düsseldorf. It was to be their final encounter before Florian’s death in 2020. Florian was the son of leading architect Paul Schneider-Esleben, and inheriting his father’s wealth on his death in 2005 was the spur to Schneider’s own departure.

“Florian didn’t enjoy replicating Kraftwerk’s music at the concerts,” reveals Bartos. “He wanted to stop touring while we made The Mix, so Ralf and I discussed Florian only working in the studio. Inheriting his father’s wealth was Florian’s freedom from Kraftwerk.

“That meeting with Florian made me very sad, because he only discussed the deal he and Ralf had made for his departure. We didn’t talk about music, just Kraftwerk as a company and Florian’s role as a shareholder. I was so unhappy afterwards.”

A similar chance encounter with Ralf was equally dispiriting: “Ralf was no longer the person I was able to compose music with. He’d become a complete stranger to me, physically and mentally. It made me very, very sad.”

NORTHERN EXPOSURE

After leaving Kraftwerk, Karl had a more harmonious relationship with Electronic, playing on Bernard Sumner and Johnny Marr’s second album Raise The Pressure in 1996. “Meeting Bernard and Johnny helped me survive leaving Kraftwerk,” smiles Karl.

“They reminded me of working with Kraftwerk at the start. My brother-in-law is from the north of England, too, and we shared the same humour, the same way of thinking. Seeing Bernard invent lyrics out of everyday language was inspiring. I love it when they call me, because we’ll talk about music. Bernard and Johnny live in music, not the stock market.”

The friendship was so inspiring that Karl nearly moved to Manchester, but Bettina’s need to work in German as a journalist meant they stayed in their home country.

Johnny also reawakened Karl’s desire to play guitar in his own music. “When I saw his huge collection of guitars and watched him play them, I became re-addicted,” grins Bartos. “I bought a Martin D-28 and play it every day, as well as piano.

Photo by Katja Ruge

“For me, music is like breathing. It’s a reflex. Of course, there are things that keep me from music, like visiting the doctor and tax returns, but I still manage to immerse myself in sound. Discipline and will also come into play. Music has to be produced, after all.”

Karl has also worked with OMD. When Paul Humphreys was out of the band, Andy McCluskey contacted Bartos to see if he’d help on a cover of Kraftwerk’s Neon Lights. Karl had already been impressed with OMD after seeing them live in the early 80s.

He and Andy wrote two songs for 1996’s Universal LP and a further two for Karl’s first post-Kraftwerk album Esperanto, released under the name Electric Music in 1993.

- Read more: Depeche Mode – the side projects

“I’m so pleased OMD are doing well,” says Bartos. “They’re an institution and I’d work with them again. Meeting them and Electronic after the end of Kraftwerk made me think, ‘Wunderbar! I’m not alone.”

Initially reluctant to release music under his own name, a self-titled second album as Electric Music arrived in 1998. Electric Music is a brilliant record, a hybrid of guitar and electro which sees Karl capture the enthusiasm gifted back to him by his new British collaborations.

It opens with The Young Urban Professional, a song initially written while recording Techno Pop in New York. Inspired by reading about the then-new yuppie phenomenon, it’s virtually Kraftwerk gone rap.

“It’s not so easy for me to remember so many words as I put into that song,” Karl admits. “I always try to think of a story and come up with a metaphor for it. It’s all about reduction, to get to the point. For me, rap is a poem that’s recited in regularly accented patterns, known as pulse groups.”

Photo by Patrick Beerhorst

With the confidence to work under his own name, the albums Communication and Off The Record followed. Communication keeps the passion of Electric Music, a teasing, faintly sinister album bursting with ideas and insistent riffs.

Off The Record was assembled from unreleased pieces Karl had written over the decades, though he reasons: “I always work with ‘old’ music. If you don’t have a writing partner, this is the only way to evaluate ideas objectively.”

Karl is currently working on a classical piece that will hopefully be released in 2023, which he describes as: “Music for synthetic symphonic orchestra in an electro-acoustic environment.” He’s also determined to “play more Bach on the piano again, although I’m not a good player. It’s immortal music.”

If the relationships in his old band became soured, Bartos is aware that at their best Kraftwerk made immortal music, too. It’s the fact they didn’t carry on trying to play together that frustrates Karl and has made it hard for him to discuss Kraftwerk for so long. As Bartos puts it: “Kraftwerk still feels like an unresolved chord, a lost golden trail.”

Ever since hearing A Hard Day’s Night, Karl has sought to make music that feels like The Beatles sounded, creating conversations and counterpoints that have resonated for generations of electronic music lovers. “I hope my music speaks to people,” he ponders.

“I don’t think about it that much. It’s my thoughts that I then translate into music. In Kraftwerk, some of us only thought about the reception of our music and how we could be more successful. We ended up cleaning up our art and becoming digital businessmen and curators.”

Karl turned 70 in May 2022. “I often think about the beyond,” says Bartos. “Life is short and I hope I die gracefully.”

If there is an existence in the great beyond, Karl Bartos will ultimately surely be making celestial, immortal music – just as he has been for so many decades. Karl might not think about it too much, but generations of music fans will carry on giving thanks to a graceful, human music pioneer.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.