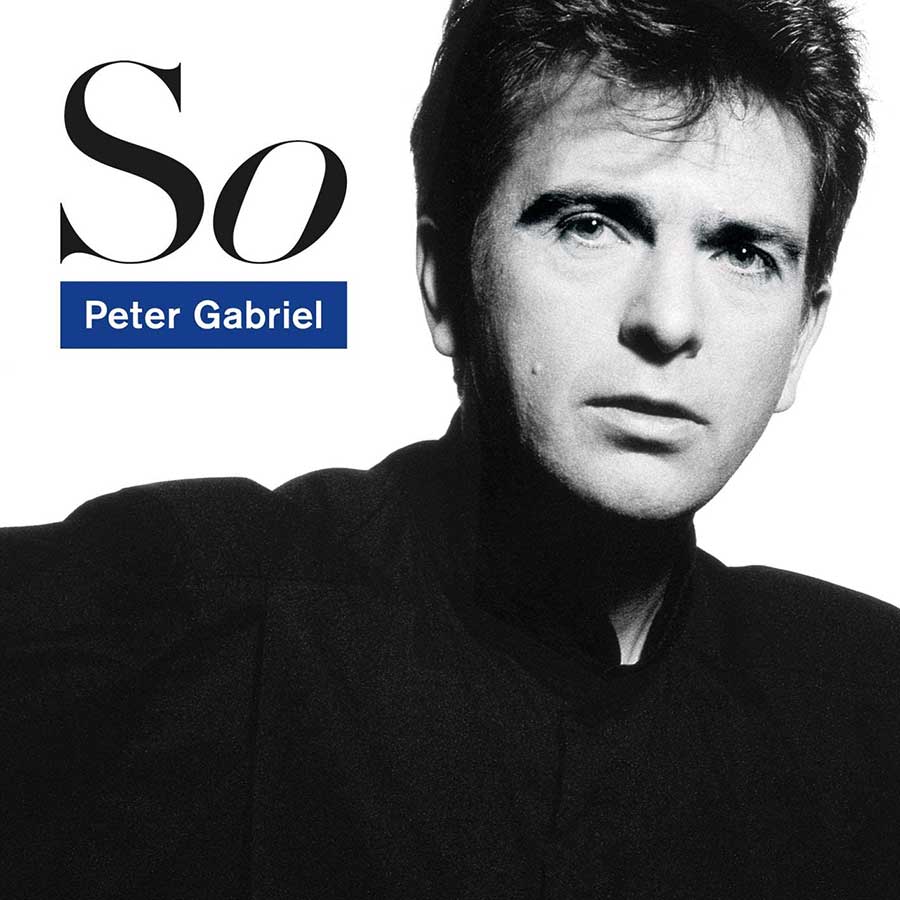

Peter Gabriel So cover

Trading the eccentric for the eclectic, with So, Peter Gabriel’s multicultural musicality took its cues from across the globe, the album’s universal inclusivity transformed its creator into a star on the international stage and a music video maverick…

While his former bandmate Phil Collins was enjoying his moment in the sun in 1985 as the continent-hopping star of Live Aid, Peter Gabriel was ensconced in the creative hub of his country estate crafting So, the funky hybrid of brash pop, R&B and World music which shot him to global superstardom and saw him emerge as an unlikely poster-boy for MTV.

A decade earlier, Gabriel had left Genesis, the band he’d co-founded and helmed to the pantheon of prog-rock royalty.

Regarded by many as the creative linchpin of the group, Gabriel was renowned for translating the mythical mysticism of their lyrics into their stage shows by donning a variety of outlandish get-ups which saw him wearing fox heads or pyramids, dressed as a sunflower or a succession of historical or fictional characters.

His shock departure from the band, due to him being frustrated at having his life planned for him in two-year cycles and his newborn daughter developing an infection which saw her life hang in the balance for her first six months, led to him seeking solace in his country house and tending to his vegetable patch.

He then slowly manoeuvred himself back into music, only releasing the results when he was confident he could do so on his own terms.

What followed was a series of eponymous albums brimming with ideas and eclecticism, which allowed Gabriel to experiment with sounds, textures and lyrics.

As visuals had always played a prominent role in his art, from the aforementioned stage costumes, to his refusal to give his records titles, Gabriel naturally appealed to writers and filmmakers. Director William Friedkin (The Exorcist) had approached him to collaborate in the role of screenwriter, a union which failed to come to fruition.

One alliance that did happen, however, was with Alan Parker, who asked Gabriel to compose the score to his award-winning film Birdy (1984).

It was that project which brought Peter together with producer Daniel Lanois. Though he was riding a wave of success after his work on U2’s The Unforgettable Fire, it was Lanois’ introspective work with Brian Eno and Harold Budd which attracted Gabriel, who was more interested in soundscapes and creating atmosphere.

Limited time constraints meant Gabriel – who disliked being rushed on projects – would be unable to write an entire score, so enlisted Lanois to collaborate, giving him license to use anything from the banks of material Gabriel had amassed from earlier projects, which included unfinished songs, alternative takes and unused demos, with the proviso that Daniel would “deliver surprises”.

- Read more: Making The Cure’s Wish

- Read more: Making Laurie Anderson’s Big Science

Thrilled with the result, Gabriel asked Lanois to stay on at Ashcombe House in Somerset to produce his next studio album, on which, he wrote in the liner notes of the deluxe edition of So, he “wanted to get back to a more traditional form of songwriting, to have some fun, to be a bit less sombre and mysterious”.

Gabriel’s desire to instil more fun into his music came from feeling that he had emerged from what he called “18 months of torment” in 1983/84.

Arriving home from his 1982 tour left him “hollow and empty”, feelings which drove him and wife Jill further apart and into couples therapy in a bid to save their marriage – an experience Gabriel found “powerful and humbling”.

“I uncovered a lot and it’s all in the songs of the album,” he told Rolling Stone magazine in 1986. “Music has always been therapy for me. There’s the idea of catharsis, learnt in my realm of interest from the blues.

“When the blues singer sits there and pours out his heart he’s purging his soul a little bit, and he’s doing so for all the audience, who can sympathise and maybe get a little emotion out, too. I know that when I can get emotion out, I suddenly feel more alive, just as if I was pulsing with new blood in a way I simply don’t when I try to suppress things.”

Confident that he was through the toughest times, thanks to Jill and Daniel, Gabriel’s newfound optimism saw him ready to begin work on the record in March 1985.

Not wanting to jeopardise his positive state of mind, and keep pressure while making the album to a minimum, rather than feel the constraints of time and money that working in a major studio would place on him, he converted the cow barn at Ashcombe House into a recording studio and bought all of the necessary equipment feeling it would ultimately prove cost-effective.

The initial sessions for So saw the barn split into two rooms, with Gabriel immersed in one, writing lyrics and developing song ideas, while Lanois, along with guitarist David Rhodes (who had just worked with Talk Talk) worked in the other, before the trio came together to develop the results and brainstorm.

The sessions were light-hearted and fun, with the musicians regularly donning yellow hard hats (their going-to-work attire) and nicknaming themselves The Three Stooges after the legendary vaudeville act.

Over the ensuing weeks (which turned into months), an elite roster of guest musicians was recruited to work on tracks including Kate Bush, French percussionist Manu Katché, Senegalese singer Youssou N’Dour, trumpeter Wayne Jackson (who had been playing with Otis Redding when Gabriel saw him in concert in 1967) and bassist Tony Levin – all experts within their field who brought the required authenticity to their respective songs, something which was especially important to Peter, who felt a responsibility in highlighting the sounds he had discovered on his travels – particularly those from Africa, South America and Spain, which were embroidered throughout So’s tracklist.

- Read more: Making Kate Bush’s The Kick Inside

“For any of us musicians who get ideas from other cultures, we get accused of cultural imperialism,” Gabriel explained in a 1986 interview with Spin. “I think it’s important to digest it a little rather than imitate it. If there’s a lack of balance, people like me have a responsibility to provide it.

“At the 1982 World of Music, Arts And Dance [WOMAD] Festival that I organised, it was exciting to have Burundi drummers playing with Echo & The Bunnymen, Indian dancers with The English Beat, Chinese opera with Simple Minds and myself – a real mixture.

“Some of the rock’n’roll cynics at the time said there was no way that audiences would take this, we’d get booed, but nothing of the sort occurred.”

At the beginning of recording the album, Lanois expected to be at Ashcombe House for a maximum of six weeks. “The truth is, we finished So almost a year to the day and that is the shortest time Peter had ever spent on an album,” he explained ruefully.

As the projected deadlines of July and December came and went due to Gabriel’s obsessiveness over the tracklisting, tensions began to rise.

Gabriel’s procrastination in particular led to heated exchanges with Lanois, who was used to working more quickly and frustrated when things ground to a halt, on one occasion smashing the telephone to stop Peter using it, on another nailing the studio door closed until he had completed writing his lyrics.

- Read more: The story of 1981

Although he had made the album completely on his own terms, Gabriel was forced to make some compromises upon its completion.

Firstly, the record company refused to allow him to release the LP with the title Peter Gabriel as he had his previous four albums. Secondly, they wanted to include a photograph of him on the cover.

Realising he had made the album with the intention of it being heard by a mass audience, Gabriel begrudgingly agreed, naming it So on account of it being an empty and meaningless word and it looking good on the cover graphically.

It was featured prominently on the Peter Saville-designed sleeve in a bold typeface alongside a black and white portrait of Gabriel inspired by David Bailey’s 60s images. “I was made to go with Peter Saville’s idea for a retro-style portrait as I was told my usual obscure LP sleeves alienated women,” Gabriel later said.

Released in May 1986, So received a warm reception from critics who praised its songwriting and fusion of styles to include elements of World music (Paul Simon’s Graceland followed three months later).

Commercially, the album was by far Gabriel’s greatest success, topping the UK charts and reaching No.2 in the US, spawning transatlantic hit singles in Sledgehammer, Big Time, Don’t Give Up, Red Rain and In Your Eyes.

So propelled Gabriel to a global level of fame he hadn’t experienced to date, either solo or with Genesis, and saw him showered with awards, become an MTV mainstay and embark on his mammoth This Way Up world tour as well as playing benefit shows for Amnesty International and Human Rights Now!.

With sales of over seven million copies, So saw Peter Gabriel hit the big time, a success made even sweeter as he did so on his own terms.

- Read more: Stephen Hague interview

Peter Gabriel: So – The songs

Red Rain

Having gone on record stating his hatred of cymbals and hi-hats and banning them entirely from his previous two albums, Gabriel was convinced by Daniel Lanois to reintroduce them for So and it is the hi-hat, courtesy of The Police’s Stewart Copeland, that opens the LP as the intro to the dramatic Red Rain.

A sonic thunderstorm, the percussive build-up of cascading drums (the result of drummer Jerry Marotta’s eight takes being pieced together bar-by-bar) is apt to compound the drama of the song’s lyrics which deal with social ills and the threat of nuclear war.

Inspired by a vivid dream Gabriel had, the cinematic descriptions within his lyrics perfectly illustrate his vision, with references to the parting of a red sea and torture (both literal and mental). Fans of Gabriel’s earlier work were rewarded by the song’s continuation of the story of Mozo – a character threaded throughout his first two albums.

Sledgehammer

A funky homage to Gabriel’s love of classic soul music – in particular the sound of the legendary Stax record label and Otis Redding whom Gabriel had seen live in London in 1967. As well as being inspired by Redding, Peter also pulled off a major coup by recruiting his trumpeter Wayne Jackson, once dubbed “the greatest horn section ever” to play on the song.

A swaggering display of braggadocio (entitled after the sex act – something which bypassed the censors), Sledgehammer stemmed from an idea Gabriel had at the very end of the So sessions.

As the musicians were preparing to leave his studio, Peter asked them to lay down a demo of the song with him, so that he could mould it into something with a view to putting it on his next album. Unable to leave it alone, he completed the track and added it to So.

When the label heard the album for the first time, they agreed with Gabriel that the song would be a perfect lead single, a decision which paid off as it was a Top 10 hit in the UK, topped the charts in the US (knocking Genesis’ Invisible Touch off the top spot), and became his biggest hit around the world, thanks in part to that innovative video.

Don’t Give Up

After the bombastic opening salvo of the previous two tracks, the soothing Don’t Give Up offers respite in the form of a haunting sonic embrace which has transcended its original inspiration – that of a man facing unemployment and an uncertain future, to be regarded as an anthem of resilience and support, thanks to Kate Bush’s wonderfully tender performance.

Originally inspired by the haunting photographs of Depression-era America by Dorothea Lange, Gabriel wrote the song with Dolly Parton in mind, but when she refused, Bush agreed to duet with him.

The sentiment of the track was pertinent to the situations of many in Thatcher’s Britain who had suffered under her leadership. A Top 10 hit in the UK, the single unbelievably stalled at No.72 in the US.

That Voice Again

Co-written with David Rhodes, That Voice Again utilises the technique of the music mirroring the lyric as its deviation from loud to quiet accentuates the lyric’s theme of judgement – veering between conscience and superego, “I’m listening to the conversation judge and jury in my head,” he sings.

In Your Eyes

Written during a trip to Barcelona, In Your Eyes began life as a song called Sagrada, based on the Sagrada Familia and architect Antoni Gaudí, before being reworked into a track rumoured to have been inspired by actress Rosanna Arquette. According to director Cameron Crowe, it was she who later convinced Gabriel to allow him to use the song in a key scene of his film Say Anything.

Originally intended to close Side One of the record, In Your Eyes was moved to the beginning of Side Two to accommodate the deeper grooves in the vinyl required for the song’s bassline and frenetic final minute which featured vocals from Youssou N’Dour. It was reinstated to its originally intended place as the closing track on subsequent CD reissues of the album.

Mercy Street

Having been introduced to the ‘forro’ sound by Djalma Corrêa during a trip to Brazil, Gabriel had written a piece called Forro. While experimenting in the studio, the tape was played at a slower tempo than it was supposed to, making certain instruments sound more prominent in the mix. Peter liked the sound of it and used it as the foundation to Mercy Street.

A song inspired by the work of poet Anne Sexton, particularly Rowing, The Rowing Endeth and 45 Mercy Street, in which the suicidal, bipolar sufferer protagonist seeks the approval of her father and God, the fusion of the haunting lyrics and lilting, stripped-back production provide a stunning alchemy.

Big Time

The third single from the album, Big Time was a return to the amplified funk sound of Sledgehammer, with everything thrown into the mix, including percussion from Stewart Copeland and vocals from PP Arnold.

Lyrically, the song satirises the emerging materialistic and consumerist yuppie culture and the shallowness of celebrities and the showbiz world. The third UK single from the album it peaked at No.13. It fared better in the US where it reached No.8, supported by heavy MTV rotation of its innovative video.

We Do What We’re Told (Milgram’s 37)

Originally recorded for Gabriel’s third album (aka Melt), We Do What We’re Told was a dreamy track inspired by

American social psychologist Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments which took two groups of people, installed

them in dominant and submissive roles and examined how that influenced their behaviour.

This Is The Picture (Excellent Birds)

Completed just 48 hours before the final deadline for the album, Gabriel came up with the idea of reworking Excellent Birds, a track he’d recorded with Laurie Anderson in 1984 and performed on TV Special Good Morning Mr Orwell.

An appeasement for some fans who worried he’d deviated too far from his avant-garde leanings, the off-kilter song became This Is The Picture, which also featured a guest spot from Chic’s Nile Rodgers. Due to lack of available space, This Is The Picture was omitted from the vinyl version of the album, only available as a bonus track on the CD and cassette versions of So.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!