New Order interview: Power, Corruption & Lies

By John Earls | September 17, 2022

Power, Corruption & Lies marked the moment when New Order completed the transformation from Joy Division. In 2020, during lockdown, NO members Stephen Morris and Gillian Gilbert told Classic Pop the truth behind the landmark album…

“Lockdown has been the same for me and Gillian as it is for everybody else: it’s pretty boring. It’s a bit like being in prison. There y’go, there’s your headline – half of New Order are in prison together.”

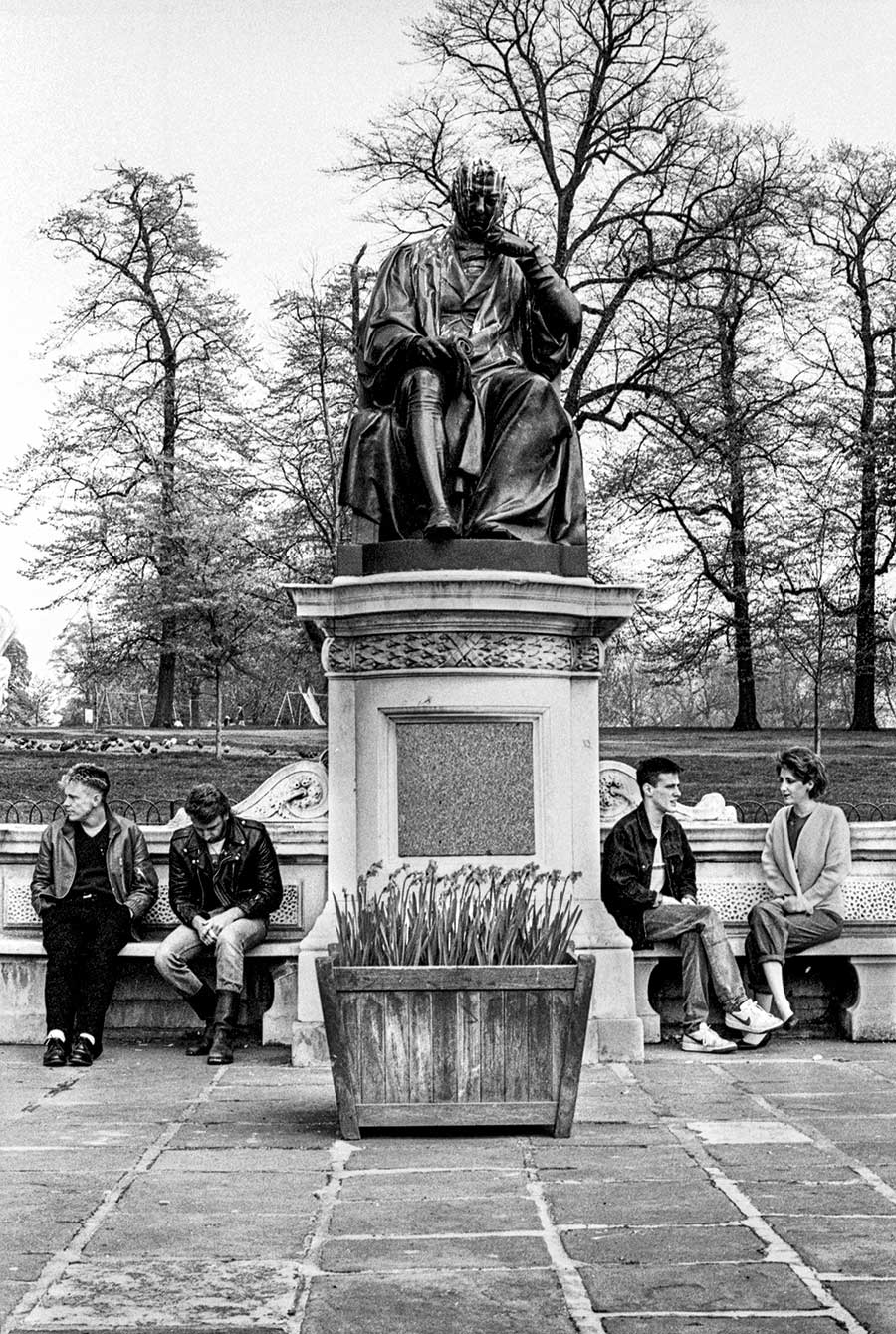

He’s a funny bugger, Stephen Morris. So is Gillian Gilbert. While Bernard Sumner and Peter Hook fought out an alpha male battle for decades until Hooky left/was fired, New Order’s drummer and keyboardist have quietly been one of the most joyful presences in music.

They appear to be exactly as you’d hope: quietly hilarious and honest about career decisions that don’t make any sense even to the members of New Order.

You’d call them “no nonsense”, but they’re both so subtly eccentric that on the sly they might be Britain’s answer to Sparks.

Stephen talks at 100mph, plainly delighted to still be in a pop band more than 40 years later, even though his insight and acuity with words would have doubtless made him flourish in his former career as a journalist.

Gillian is more considered, pausing before delivering a succinct one-liner. They had the self-awareness of their quiet reputation to call their New Order splinter group The Other Two, but there are few sharper minds in pop.

You don’t get to stay together as a couple for 40 years in music without knowing most of life’s secrets.

- Read more: New Order – album by album

That said, even Gillian and Stephen haven’t figured out a way to make lockdown life too enjoyable. In isolation, New Order managed to finish their first new single since their wonderful Music Complete album, the storming Be A Rebel. But it wasn’t exactly an easy process.

“You can’t beat being in the same room,” Stephen explains. “We normally talk through decisions like, ‘How do we want the bass to sound here?’, but over Skype that’s painful. We’ve shown that making a single by remote control is doable because of modern technology, but that doesn’t mean it’s enjoyable.”

Gillian reveals Be A Rebel is “really a leftover song”, written for Music Complete but which didn’t fit that album’s full-on pop style. Gillian and Stephen formed one isolation team to work on the track, with Bernard, guitarist Phil Cunningham and bassist Tom Chapman the other half.

“Bernard finished the main song, before me and Stephen mixed it,” says Gillian. “Mixing mainly involved putting more of Phil and Tom on…”

Stephen laughs when he’s reminded New Order’s average of releasing an album every five years means the lack of a follow-up to 2015’s Music Complete sees the band starting to look a bit tardy. “It’s a good point and I’d like to say there’ll be a new record soon,” he ponders.

“But asking when New Order will make a new record is a hard question at the best of times. With the pandemic, we’ve been thinking about, ‘When can I go to the bloody shops?’ more than a new record. Once it’s safe for everyone to be in a studio again, it’d be good to get together and start writing.”

If a new album is some way off, at least there’s plenty happening in New Order land, chiefly a boxset of Power, Corruption & Lies.

Although 1981’s Movement is New Order’s official debut album, its successor is where the band properly became a separate entity from Joy Division after Ian Curtis’ death in 1980.

“To me, Power, Corruption & Lies is the start of New Order,” agrees Stephen. He adopts a mock-earnest tone. “’It’s when we cast off the shadow of Joy Division.’ That’s a horrible cliché, but we really did discover something fresh on Power, Corruption & Lies, a new sound that took us away from Joy Division.”

It was also the album where Gillian really felt an established part of New Order. The continuation of Joy Division producer Martin Hannett working on Movement made for an uncomfortable initiation.

“Me being in the band, I don’t think Martin was having any of it,” Gillian explains. “Everything was obviously weird after Ian died, and Movement was definitely a weird experience. Me and Martin didn’t gel and we’d had a few clashes.

“Producing Power, Corruption & Lies ourselves was very much a new beginning. That’s not just hindsight, it felt like a fresh start at the time. New Order were becoming a little gang of our own, going further away from Joy Division.”

Producing themselves seemed an obvious move, especially once Martin fell out with Factory Records boss Tony Wilson, though Stephen initially had doubts that taking control would help them get on. “We’d had enough of Martin and I knew we could do it ourselves,” he recalls.

“But I was worried there’d be too many producers in the band – I wondered if we’d need another person from the outside to come in, to act as referee.”

Stephen’s fears were unfounded. Hooky was closest to the mixing desk, losing himself in 2000AD comics between takes, as the record saw New Order act as a Factory factory.

“Everyone had been an equal partner in Joy Division,” says Gillian. “I found that hard at first, because I’d never been in a band that wrote music before New Order. Everyone was very supportive and encouraged me to be part of the writing team.

- Read more: The Lowdown – New Order

“I can still remember writing the bass notes for Age Of Consent and thinking, ‘Yes! I’ve finally broken through!’ It was a really helpful atmosphere, there was no element of anyone acting like they were further ahead than me.”

Gillian took over programming sequencers in concert, changing the numbers in their coding during gigs, while Stephen’s love of gadgets meant that the couple shared programming work in the studio.

“I’m not sure if Power, Corruption & Lies is dance music as such,” reasons Stephen. “It was more about using technology that was very new and exciting at the time, to see what could be done with it. The album is effectively a rewrite of songs we’d already written for Movement.”

Tracks such as Ultraviolence, The Village and We All Stand dated back to the debut album sessions, but were upgraded along with the band’s technology as Stephen got to grips with instantly-forgotten synths including the Alpha Syntauri.

“We’d written a few songs on clunky old drum machines and sequencers,” says Morris. “Once we got the new equipment, we basically wrote them again. 586 was always a loose jam, then Bernard turned it into something else when he came up with the Giorgio Moroder-style dark intro. The technology really wasn’t that great – Space Invaders machines had better tech.

“I’ve been digging out the manuals for those sequencers again recently. Flicking through them now, I think, ‘Is that all this really did?’, but it forced us to squeeze every last drop out of what the gear could do.”

Gillian laughingly confesses she was happy to let her boyfriend crack the technical aspects.

“Stephen and Bernard loved that side,” she explains. “Because he was into the technology, I’d say to Stephen, ‘Hey, could you just do that bit for me?’ I didn’t have to be that hands-on until it came to the end – putting each note into the sequencer so we could play songs live, figuring out how to keep time so everyone knew when to come in.

“That’s the side I loved. I’d be an extra pair of hands for Bernard, too, him saying, ‘Can you play this?’ He’d get excited at what I’d add, going, ‘Ooh, what did you just play then?’”

If Bernard was happy to hand over some of the music responsibilities, Power, Corruption & Lies saw him take control of lyrics. Stephen had enjoyed writing lyrics “fuelled by Carlsberg Special Brew” for occasional B-sides, but Sumner announced he wanted to take sole ownership of the words.

- Read more: Remembering Manchester’s Haçienda

“I understood that,” Morris accepts. “Bernard’s lyrics have always meant something to him, even if he forgot most of them in concert and made them up on the spot! We’d still help him out in the studio, as you’d often hear Bernard going, ‘No, that’s shit… I’m stuck for a line here. Anyone?’

“Bernard is brilliant at improvising lyrics. In the gap after Movement, we were effectively writing songs live on stage and it took a lot of guts for Bernard to go on stage with nothing.”

The ”Up, down, turn around!” chorus of Temptation was improvised after Bernard microdosed on leftover acid before a show.

“Even in the middle of the gig, when Bernard started singing that, I thought, ‘Fuck, that’s brilliant!’ – and not just because, for once, Bernard’s improvised lyrics weren’t totally obscene,” says Stephen.

“The lyrics on Power, Corruption & Lies were largely from assembling the best bits of the improvisations that Bernard came up with on stage and in the studio.”

In the middle of it all came Blue Monday. Seeking to show what all this new technology was capable of, the band were astonished when New Order manager Rob Gretton declared it sounded like a hit.

“Blue Monday was just a big experiment,” insists Gillian. “We’d recently got our first recording studio, which had a different feel to recording in our practice room. We just wanted to see how far we could go in studio recording. When Rob said, ‘This is massive!’ we all went, ‘You what?’, because Blue Monday didn’t sound like anything else around at all. Which, looking back, is obviously part of its appeal.”

Famously, it was also designed as a song that the band could use instead of an encore. Stephen recalls: “Encores were what proper pop bands did, and we didn’t want to be a proper band at all. Encores? Bloody showbiz!”

Gillian adds: “Blue Monday sounds so regimented because we wanted the sequencers to be able to play it while we walked off stage, refusing to come back on. We wanted to find a robot that could sing all the words. Having a hit with a song like that never occurred to us until Rob got excited.”

Of course, Blue Monday promptly became the best-selling 12″ single of all-time. Maybe.

“Well, that’s what Tony Wilson always said,” laughs Stephen. “But he had no idea at all if that was remotely true, and nor did we. Because Factory weren’t part of the BPI record companies collective, it wasn’t until 10 years later that we’d find out how many copies we’d sold of anything. Saying it’s the best-selling 12″ of all time is a good story, though.”

The drummer is less enamoured of the other great myth surrounding Blue Monday – that designer Peter Saville’s die-cut sleeve was so intricate to manufacture that it lost Factory 5p for every copy sold.

The drummer is less enamoured of the other great myth surrounding Blue Monday – that designer Peter Saville’s die-cut sleeve was so intricate to manufacture that it lost Factory 5p for every copy sold.

“That myth instantly defeats the ‘best-selling 12″ ever’ myth,” Stephen points out. “If we were losing 5p a copy, the Haçienda would have shut down immediately, because we’d have taken money out of the club in order to sell people copies of this ruinously-expensive 12″.

“If you look at Peter’s artwork around that time, he was obsessed by die-cut sleeves. His sleeve for OMD’s Dazzle Ships had even more holes than Blue Monday, and nobody says OMD went bankrupt off that album. It is true that, when we got the first printers bill, we looked at the cost of the sleeve and went, ‘How much?! Right, get rid of those holes!’”

As if New Order weren’t busy enough, creating gigantic standalone singles at the same time as reinventing themselves on their album, the Haçienda was being built during the recording of Power, Corruption & Lies. One of the essential extras on the boxset is a homecoming gig at the Haçienda in 1982.

“My mum and dad came to that show, so it’s probably my favourite ever Haçienda memory,” Gillian recalls. “They hadn’t really known what I did before, and the whole show was one big party. My mum used to watch Tony on television, but she hadn’t met him before.

“She wasn’t trying to be nasty, but she said to him when she finally met him that night, ‘I can see now why people don’t like you.’”

Would New Order have gone through with the Haçienda as a great art statement if they’d known how big a pain it would prove?

“Well, that’s the point – we had no idea how much of a pain it would be,” responds Gillian. “While you’re in the studio, you trust the people around you to sort it all out. And everyone around the band was so optimistic, we just went with the flow. We were told it’d work – ‘If you just do this, it’ll pay for that.’ ‘Really? Oh, OK then.’”

Stephen continues: “Like everything Factory did, the Haçienda looked fantastic. But it didn’t sound fantastic at all. As a club, it just didn’t work, even though Hooky spent a long time helping to get the sound right eventually. It lurched from one disaster to another.

“We were always trying to convince ourselves it’d work, but it was a step too far. I saw Netflix’s documentary about Studio 54 recently and, my God, if only we’d known about that club at the time. We made every mistake Studio 54 had a couple of years earlier all over again.

- Read more: The story of Factory Records

“But the Haçienda was still fantastic and I don’t regret doing it. Factory generally, and the Haçienda in particular, changed so much in Manchester, if not the world.”

So, things were pretty frantic for New Order. Doubly so for the couple trying to start a life together in the middle of it all. Given the mythology around Joy Division and New Order, it’s easy to forget that, even by the latter band’s second album, Stephen and Gillian both still lived with their parents.

“We didn’t know any different,” reasons Gillian. “We’d only just started going out together when I joined, so it felt natural and New Order was our whole life at that moment. It wasn’t until we got our own house that we probably felt like a regular couple, with a life away from the band.

“Once we started having children is when our life started getting in the way of the band, but that’s true of any regular job and that’s part of growing up anyway.”

Stephen adds: “We didn’t consider how it would affect us as a couple when Gillian joined the band. Because Gillian had been a Joy Division fan, it was just, ‘How brilliant!’, not realising it would completely take over our lives.

“It was a gradual encroachment, so wrapped up in New Order becoming more successful, that we simply became acclimatised.

“It was all-consuming, but then we started to think about having children. And we waited to have kids, because we thought having children would fuck up the band: ‘But we won’t be able to go on tour!’

“It’s only looking back that I think, ‘Why the hell did I think more of the band than my own life?’”

Gillian is proud that she and Stephen “didn’t have many arguments” among the frenzy, though in his new memoir Fast Forward Stephen admits selfishly starting a shouting match with his future wife on a stopover in Thailand returning from an Australian tour to promote Blue Monday.

“Oh, I try not to think about the arguments,” Gillian laughs. “Stephen is very easy-going, right up until the moment he isn’t. He’s someone who, when they’re nice, they’re lovely, but when they’re not, they’re really horrible. There’s no in between with Stephen, and Thailand was a good example of that.”

Asked about the argument, Stephen admits: “That was when I thought, ‘Fucking hell, the band have been overdoing this a bit.’ It was a row that could have happened to any couple, except that everything gets blown out of all proportion when you’re with the same four people all the time.

- Read more: Making Technique

“The shows in Australia were when we were still figuring out how to play Blue Monday live – as soon as we got to the other side of the world, we had to go in yet another bloody rehearsal room to figure out Blue Monday live. That sort of thing carried on and on and on until I stupidly lost the plot in Thailand.”

Of course, if you want arguments in New Order, look no further than Bernard and Hooky – though even their fights were once largely mythical, too.

“When you read about New Order now, it sounds like Bernard and Hooky were at it hammer and tongs for 30 years, and it wasn’t like that,” emphasises Stephen.

“Most of the time, we had a laugh. It gradually got worse between them as the 90s wore on, and it was everybody’s fault – mine, Gillian and Rob Gretton’s as much as Bernard or Hooky’s, because we forgot who we were. Bernard and Hooky have both got valid points of view, but they just won’t reconcile.

“They refused to get together to try to sort their differences out, and there’s nothing anyone else could have done.

“It was an awful situation to be in, and it got to the stage where for both of them to be in the band would have meant New Order being cheesy chalk or chalky cheese. I always try to see everyone’s point of view, but sometimes it can’t be done.

“They were at school together, they grew up the same kind of person. For whatever reason, they turned into different kinds of people. It’s very sad.”

Gillian admits the atmosphere making New Order’s 2001 album Get Ready meant she was initially cautious about returning to the studio for Music Complete.

“I figured doing an EP might be OK, but Bernard wanted to do a whole record,” she recalls. “That made me think about the bad old days, especially Get Ready, when I’d been glad to get out of it all.

“But the bad old relationships around Factory had gone, which had caused a lot of problems with a hierarchy becoming established within the band.

“Phil and Tom are very easy-going. It was a refreshing new start, where I felt that I could do anything – so I did. I came in to Music Complete with a lot of ideas, and it was a record where everyone’s ideas were thrown in together.

“We worked up ideas on our own, rather than doing it en masse with everyone looking over your shoulder at what you’re doing on your computer. It was a great way of working and I’m very proud of Music Complete.”

Gillian is right to be proud about Music Complete, one of New Order’s albums worthy of a boxset to accompany Power, Corruption & Lies one day. Once New Order can be together again, hopefully a record as strong as those two will emerge. And at the heart of it all will be the quietly wonderful other two.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!