Nik Kershaw interview: Beautiful nightmare

By Felix Rowe | September 16, 2022

In 2020, with an eclectic new album on its way, Classic Pop caught up with reluctant star Nik Kershaw to talk writer’s block, making history and his eagerness to return to the live stage…

“Terrifying” is a word that comes up a lot in conversation with Nik Kershaw – typically when he’s describing a momentous career highlight, whether that’s performing to a packed stadium at Live Aid or stepping into the shoes of his idols.

Accustomed as we are to putting pop stars on a pedestal, it’s sobering to discover that living the dream can occasionally bring on emotions usually associated with a nightmare.

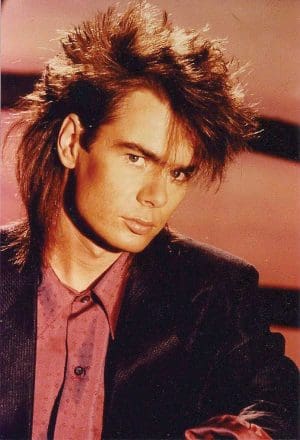

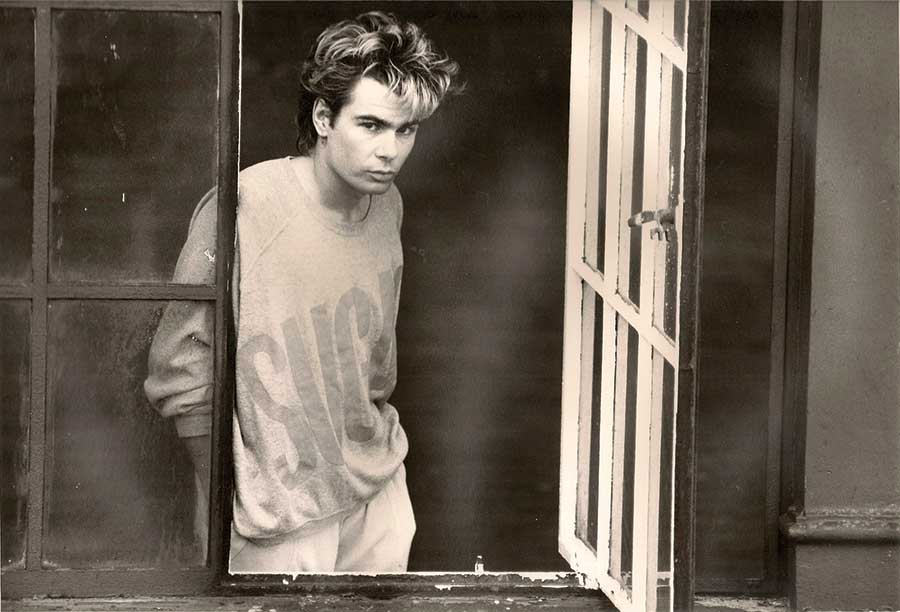

When he arrived on the scene in 1983, with his chiselled good looks, razor-sharp cheekbones and even sharper tunes, Kershaw embodied the perfect pop star.

A one-man Duran Duran multi-instrumentalist who didn’t just look the part but wrote his own string of hits: Wouldn’t It Be Good, I Won’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me and The Riddle among them.

But the shoulder pads and outer bravado helped to mask an innate imposter syndrome. The terror he recalls was that of being exposed as a fraud; that despite his talent and success he didn’t deserve to share the exulted status of his contemporaries.

“Early on, I was terrified of getting found out,” he tells us. “So I used to go out of my way to write nothing about me. It was always third-party, or playing a role, imagining things from other people’s perspective.”

He struggled, too, to handle the attention and adulation that comes with the territory. His growing frustration and unease with industry shallowness and the media manifested itself on self-produced third album, Radio Musicola.

But the young Kershaw was hardly a shrinking violet. Elsewhere in our conversation, when singing the praises of The 1975, he says, “I remember being that confident in my own abilities, thinking everything you do is fabulous. You know, everybody’s gonna love what you do, you just do it and get it out there.”

So Oxymoron is an apt title for Kershaw’s latest album – his ninth and first in eight years. That tussle between self-belief and niggling doubt is probably central to many an artist’s longevity.

Out of the shadows

Like most things, Kershaw’s return to the spotlight has been overshadowed by worldwide events. Written before the onset of lockdown, the first line of opening track The Chosen Ones is eerily prescient, essentially summing up 2020 for many people: “Here, we are safe, we are wrapped in our bubbles/ Disinfected trouble, we can’t begin to know.”

Having retreated to the countryside many years ago, the Kershaw family have ridden out the storm at home in a small village on the Suffolk borders, hanging out in the garden and taking long dog walks.

“I’m not particularly sociable anyway!” he says. In the meantime, he teased fans with a taster EP.

Oxymoron is an eclectic mix, showcasing his musicianship, songcraft and signature wordplay.

Can’t Go On has a gentle reggae vibe that brings to mind Culture Club; I Do Believe showcases the knack he shares with Stephen Duffy for crafting hook-laden guitar pop; and She Gets Me recalls a slightly funkier Robbie Williams fronting The Brand New Heavies.

Then there are folkier moments and orchestral sweeps, too.

At 16 tracks long, it doesn’t seem that he was exactly scrabbling for material. But, as Kershaw explains, the writing process was a bit more pained than it might appear.

“It becomes more and more difficult to write, or to make yourself happy, the longer you get into your career. You lose the ability to surprise yourself – you pick up the guitar, and oh, it’s those chords again!”

He echoes this sentiment later, noting that “sometimes the simple things are the most difficult to write.”

As a result, early efforts were marred by the onset of writer’s block.

“I went through a period of probably more than a year of dismissing anything that came into my head. I was quite down on myself. Then I remember just going into the studio one day, and thinking, ‘Well, you know what, I’m going to write a song a day. It doesn’t have to be a good song, it’s just going to be a song.’”

That flurry of activity produced around 20 new tracks, with half a dozen of them – including These Little Things and “another quick one” Cloudy Bay To Malibu – making the final cut.

“I like to write the initial draft of a lyric as quick as I can, because then you get the rhythm sorted. Some of it you know is nonsense, but that doesn’t matter, you just get the phrasing, the meter of the words. And it’s quite amazing when you do it that quickly how little you actually have to change to make it make sense.”

It’s at this point that new song The Best I Can springs to mind. We’re pretty sure he sings the curious line: “I come with many uses, like Vaseline does.”

When he started the process in his home studio, Kershaw tells us: “There wasn’t a masterplan as such, I was just writing some songs and messing about, you know. It wasn’t definite there was going to be another album.”

But the time came when it was necessary to upgrade for the finishing touches. So what better choice than Abbey Road? Obvious heritage aside, the studio has its own personal resonance for Kershaw.

He worked in the very same room where he recorded with a young chap called Chesney Hawkes nearly 30 years before – “That’s synchronicity for you.” But more on that later.

There were more practical considerations, too, in achieving the big sound he was looking for. “Part of the problem is that there just aren’t that many studios left where you can do that kind of thing, unfortunately.

“Abbey Road is still a byword for excellence. There’s a reason why they have that reputation, so you go there for that reason, not the reputation itself.”

Recording the string section was a particularly magical moment. “It’s a room full of people who have never heard what’s in your head, and then they start playing it back to you, it’s just extraordinary. A wonderful process.”

But, apart from his keyboard player who recorded some piano and keys, Nik’s live band didn’t get to share in that process.

“I’ve often been rude enough to ignore them!” he says, sounding slightly embarrassed. “For me, recording is a such a separate space – this magical, huge toy box, so if I can get more toys to make me sound different…”

Becoming an idol

When it comes to his early influences, Kershaw’s answer is a familiar one.

“It was Bowie that made me decide this is what I’m going to do. Totally. I was vaguely interested in music, but it seemed to go with my peer group and whatever they were doing; whatever fashionable clothes I was supposed to be wearing. Little trends and tribes.

“At one point I was a skinhead so I had to listen to reggae, that’s what you did. I enjoyed the reggae, but I did that because I was part of that tribe. I think Bowie was the first time I saw something and just thought, ‘That’s blown my mind. That’s incredible.’ David Bowie didn’t come from any of the tribes, he was just there all of a sudden beckoning to you.”

So, it must have a felt a little strange a few years later to be sat on a minibus leaving Wembley Stadium, Bowie in the seat behind, singing Do They Know It’s Christmas? From worshipping these idols to sharing a stage with them and becoming one yourself…

“That was a pretty surreal thing, almost impossible to get a handle on it – to get a hold of that feeling and think, ‘I’m here now.’ I never felt that I was in the same position, that I belonged there. I had a kind of imposter syndrome for most of that time.

“I was terrified of getting found out. I had only been going for about a year and a bit when Live Aid happened, so I was in some pretty exulted company.”

He recalls arriving by helicopter, meeting Charles and Diana, then watching Status Quo kick things off from the Royal Box. But again, it wasn’t a moment he got to enjoy.

“I remember nervously thinking about how I was going to get out; what the protocol was for leaving the Royal Box if the royals were still there, because I’d have to go past them to start getting ready. I sat there getting more and more nervous, and eventually they got up and left, which was a bit of a relief.”

“I remember standing in the quadrangle feeling really nervous and getting calmed down by having a chat with Sting, which was pretty surreal in itself. I also recall standing at the side of the stage being absolutely terrified. The only bit about the actual gig that I remember was forgetting the words to Wouldn’t It Be Good and then having to improvise quickly.

“That was one of the most terrifying moments of my life, and then coming off and just the relief of having got away with it. Then, of course, I’m sitting there watching Queen, knowing at the time that there’s something rather special happening.”

Songwriter for hire

One career highlight he recounts without once using the T-word is the massive No.1 hit he wrote and co-produced for Chesney Hawkes. Notably, it relates to stepping out of the limelight to focus on writing.

“That was just brilliant. All the reasons that I stopped recording, the unwelcome attention, my problems in dealing with all the public thing, being judged and all that kind of stuff, all the problems weren’t there – Chesney was dealing with it all. I was just sitting in an armchair drinking Merlot and watching it fly up the charts.

“It was just fabulous. I thought this is how it’s going to be for me writing and producing songs, which obviously it didn’t turn out like that. That was as successful as it got as a songwriter.”

He continues: “When I first started writing what I thought was material for other people, the one criticism levelled at me from any publisher that I took the songs to was, ‘Well, it sounds a bit like Nik Kershaw.’ OK, that’s a problem! The problem being that I demoed them as well, so it’s got my voice on them.

“The One And Only was one of the first songs I took to Warner Chappell Music on a cassette full of demos. I didn’t attach any magical powers to that particular song, it was just in a bunch of about 20 others. I don’t even think it was first one.

“Pretty much the day after I got a call saying some bloke called Chip Hawkes has come in, who used to be in The Tremeloes. His son is in a film with Roger Daltrey and they love The One And Only...”

The song, which features Kershaw on guitar and backing vocals, spent five weeks at the top of the UK singles chart. It was such a colossal success, in fact, Chesney Hawkes couldn’t shake the ‘one-hit wonder’ tag, but he still woos crowds with it 30 years later.

In another bizarre twist, the track has taken on another life, thanks to David Bowie’s film director son, Duncan Jones, who playfully uses it as a calling card in his movies, from Moon and Source Code to Mute.

“When I was visiting Ches in Los Angeles, we met Duncan for a coffee and he did remind me so much of his dad, it’s ridiculous. I knew him as soon as I saw him. He does try to shoehorn it into every film he makes.

“He failed with Warcraft, but he did try. I think there was an occasion where he flew Chesney up to the location and they did a minstrel version, or a pirate version, with him playing a lute.”

We’re sure Classic Pop speaks for many people in saying that’s something the world definitely needs to see.

Hello, Yellow Brick Road

Since this commercial high-water mark, Kershaw has retained the respect of his peers. Even when not chasing it, they keep tracking the ‘imposter’ down to work with him. A recurring figure is Elton John, after first crossing paths at a Radio One gig at Wembley Stadium in 1984.

Their friendship developed following a show in Paris that year, and before long Nik was enjoying Sunday lunches at Elton’s house in Windsor, and playing guitar on Nikita from the Ice On Fire album.

“He was a really encouraging champion for me. He’s still great at doing that now with new artists. He’s really hungry for music. I remember bumping into him once randomly in Tower Records on the Sunset Strip in LA. He was wheeling this massive trolley about, completely full of new vinyl.”

Elton invited Kershaw to write a song for his 1993 Duets album – other guests included Gladys Knight, Leonard Cohen and Little Richard. “That was right out of the blue. I’m like, ‘OK, Elton John’s asking me for songs!’”

Kershaw scrambled a couple of ideas together, and one of these was the appropriately-titled Old Friend. “I was in Metropolis Studios sitting behind the control desk with Elton in the vocal booth.

“My words were coming out of Elton John’s mouth, and I thought, this is just the weirdest thing,” he laughs. “Having to produce and vocally coach Elton, it’s just bonkers. But he was brilliant about it – he wanted to get it right and please me.”

Even more out of the blue was a call from another hero, Genesis’ Tony Banks – “I’ve got no idea where he got my phone number from!” – to work on several tracks for his 1991 solo album, Still, at the group’s legendary studio, The Farm. More recently, he featured on guitarist Steve Hackett’s Genesis Revisited II, via mutual friend, Kajagoogoo’s Nick Beggs.

“I picked The Lamia – I didn’t really realise what I’d bitten off there. I should have done a bit of research to think what can I actually sing! One thing I realised about Peter Gabriel is what an incredible range he has. I think I did OK.

“Then Steve decided he wanted to play some gigs. They were terrifying, stepping into Peter Gabriel’s shoes, standing in front of Genesis fans trying to make sure I don’t get the words wrong.”

But, if it’s being in the public eye that has most troubled Nik over the years, this hasn’t stopped him pining for a return to the live arena, as and when lockdown resides.

“It would be lovely to get on stage with the band again, just to have that feeling. Because it’s another world – that square footage of stage that’s yours for however many minutes, I do miss being in that space.”

- Read more: Nik Kershaw – album by album

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!