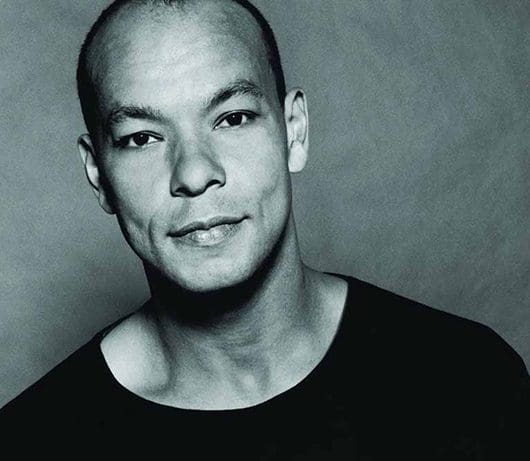

Nik Kershaw interview: “It’s still a buzz, walking out and hearing people sing those songs back to you”

By Classic Pop | October 17, 2022

In 2017, as he was about to embark on an Icons of the 8Os tour with Go West and Cutting Crew, Nik Kershaw met Classic Pop to talk stage fright, the power of Bowie and Bolan and the enormity of Live Aid… By Douglas McPherson

Nik Kershaw is no stranger to the spotlight. In 1984, he spent more weeks on the chart than any other solo act and the following year he took part in that decade’s biggest music event, Live Aid.

While he is still wowing crowds over 30 years later, his impeccable performances belie the nerves that have always gripped him before he hits the stage.

Recalling his earliest attraction to the limelight, he says: “I was in local drama groups from the age of about nine until I was 12. I guess something in me wanted to show off. I don’t know what it was though, because the thought of getting on stage terrified me at the same time. It’s a weird conundrum and I’m still struggling with it now.”

But the singer, who made his name with such evergreens as I Won’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me, Wouldn’t It Be Good and The Riddle, acknowledges: “I enjoy being on stage and I enjoy that contact with people, but I’ve always been very nervous about actually doing it. I still get a bit of, I won’t say stage fright, but I certainly get nervous.”

Growing up in Ipswich, Kershaw inherited his performing gene from his parents. His mother was a keen amateur singer.

“She was classically trained and had thoughts of doing it professionally at one point, but it wasn’t easy in her circumstances,” Nik says. “She ended up in an office, got married and had kids, but she was always singing in little concerts around the town.”

His father was an amateur flautist who also played locally. “My dad was a bit of a character,” Nik chuckles. “He ended up being an architect, but he should have run away with the circus. He used to play comedy piano at office parties and things like that.”

Kershaw quickly gravitated to music: “There were two musical instruments that were always around in our house, a beaten-up old piano on which I used to whack all the black notes, and a Spanish guitar which someone had strung with steel strings and painted with white emulsion. I started strumming that when I was 12 or 13.

“Before that, I learned violin for about two years, but that’s an excruciating instrument to listen to if you don’t know what you’re doing, whereas with guitars and pianos it’s not that hard to make them sound reasonably good.”

His interest in six strings intensified a year or two later when a school friend got an electric guitar. “I used to go around to his house and pretend I was Marc Bolan,” he recalls.

“We formed a school band and I was just singing at that point. Then I got myself an electric guitar and locked myself in my bedroom for a couple of years, learning Ritchie Blackmore solos.”

Blackmore was the riffmeister from Deep Purple and Rainbow, but Kershaw identifies David Bowie as the man who: “finally tipped me over the edge”…

“I remember seeing an early evening TV documentary about Bowie that really turned my head. I thought, wow, that is something special. The seminal album in my formative years was Aladdin Sane. I listened to it over and over again. But the second single I ever bought was Get It On by T. Rex.

“That was the first time I ever heard stereo, with one guitar coming out of the left speaker and one coming out of the right. I thought that was amazing.”

Big shoes to fill

As a teenager, Kershaw played his first original material in a band called Hogg. Then, when he was 20 and working in an unemployment office, he was headhunted by a professional band called Fusion.

“They were the band that all the musos used to go and see in one of the pubs in Ipswich. They played Steely Dan and Weather Report – all the tricky stuff and didn’t miss any notes out.

“Their guitarist left and their bass player asked me if I’d like to try out for the gig. I thought it might be beyond my capabilities so I was initially reluctant but eventually said yes.”

However, Fusion didn’t just play fusion. That was just a bit of spare-time fun for a function band that made its living performing at weddings.

“So my first gig was at this pub, doing all the jazz fusion stuff, and then the second was at Walthamstow Town Hall where I was expected to busk to two-and-a-half hours of dinner dance music.”

In dinner jackets…?

“It was even worse than that!” Nik laughs. “We had a band uniform and the previous incumbent of my uniform was 6’ 4” – which I was not. I ended up rolling up the trouser legs and sleeves and trying to figure out what the hell I’d let myself in for, because I had no idea how to busk.”

- Read more: Nik Kershaw – album by album

- Read more: Nik Kershaw 2020 interview

It was during his stint with Fusion that Kershaw made his first visit to a recording studio. He wrote and recorded some songs with the band’s pianist, who had a record deal, although nothing was released.

When Fusion split, Kershaw found himself back at the unemployment office, but this time on the other side of the desk.

While he was unemployed, he tried to interest record companies in himself as a solo artist without success. His luck changed when he advertised for a manager in the back pages of Melody Maker.

“It was a last roll of the dice,” he admits, but he threw a six and his ad was answered by Mickey Modern who managed Nine Below Zero. “All of a sudden, I had an album deal with MCA.”

Racing up the charts

Most of the songs on Kershaw’s debut album, Human Racing, were written in his home at the time, a remote farm cottage in the Essex countryside that he says: “Was notable for being colder on the inside than it was on the outside. I made the demos on an old Portastudio, one SM58 mic and a beaten-up old drum kit that I’d borrowed.”

Among the songs was his first single and most lasting anthem, I Won’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me. “That was one of the few that came from me strumming a guitar,” he recalls.

“I was strumming a few chords and singing aimlessly over it and those words came out. There was a big CND thing at the time, so I was writing about that. It was quite folky, really – more Dylanesque than a pop song.”

Whether every record buyer got the ‘ban the bomb’ message or whether they just loved that irresistible singalong chorus is a moot point, Kershaw admits.

“I was never madly happy with the final recording, which wasn’t anybody’s fault but mine, but there did seem to be a disconnect between the verses and the choruses, which were quite jolly. I didn’t mean them to be that jolly, because it was a protest song.

“But I don’t think it really matters if people get what you’re on about. They will get whatever they get out of it. You don’t really look at why people are buying records when they’re buying them. You only look at that when they stop buying them.

“At the time I can’t say if they were buying my records for the music at all. Maybe they were buying them because I was in Smash Hits and on the telly and looked okay in a poster on their wall.”

Interestingly, I Won’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me failed to crack the Top 40 on its initial release, although it went Top 10 in the Netherlands. It was only after Kershaw’s second single, Wouldn’t It Be Good, made the UK Top 5 that I Won’t Let The Sun Go Down was re-released and shot to No.2.

Other hits followed with The Riddle and Wide Boy which made Kershaw perfectly placed for a slot on the defining concert of the 80s: Live Aid.

“I wasn’t involved with the Band Aid single – I wasn’t in Bob Geldof’s telephone book at that point, but we were vaguely aware that some kind of gig might be happening in the summer,” he says.

“Bob was lurking at Heathrow Airport one morning when a load of artists were flying out on the same plane for a big festival in Germany. Bob wasn’t going with us. He was just jumping on people and saying, ‘Are you up for doing something?’

“I’d met him once before at Top Of The Pops, when he turned up with some Feed The World t-shirts for everyone to wear. So I said: ‘Yeah, sure, absolutely,’ because you don’t say no to Bob Geldof.

“At the time, they were talking about the Hammersmith Odeon and then it grew from there: Wembley Arena, then Wembley Stadium. Then Philadelphia came in and satellite links and all the TV companies… and I thought: what have I let myself in for?”

Kershaw has described going on that day as ‘terrifying.’ As for how all those egos got on backstage, he says: “I didn’t see any tantrums. You knew you weren’t going to get a soundcheck. You were just praying that your gear was working when you went on.

“But you can’t say people left their egos at home, because if Freddie Mercury had done that he wouldn’t have been able to put on that show. It was astonishing.”

Buddy movie benefits

After his last Top 10 hit with Don Quixote in 1985, Kershaw’s chart career began to fade. At the dawn of the 90s, however, he was to write and produce his only No.1, when Chesney Hawkes recorded The One And Only, initially for the soundtrack of the Roger Daltrey film Buddy’s Song, in which Hawkes starred as The Who frontman’s onscreen son.

Nik said: “When my deal ended with MCA in 1989, I’d done my four albums with them and I wasn’t really looking for another deal. I decided I wanted to quieten things down a bit and see how I got on working in the background, writing and producing.

“The One And Only was the first one out of the bag. I stuck it on the shelf and forgot about it and it wasn’t until about a year later that Chesney’s dad, who was managing him at the time, walked into my publisher, Warner Chappell Music, and said: ‘Have you got any songs for this movie?’ He took the demo home, played it to Chesney and they both said that was the one that they wanted.”

With a typically self-deprecating chuckle, Kershaw says: “I thought, this is easy! You write songs, people record them and they’re massive hits! But, of course, it’s not like that. I had to learn how to write a song that anybody can sing.”

Born of frustration

He had some successes, with Cliff Richard recording Healing Love, The Hollies cutting The Woman I Love and boyband Let Loose scoring a hit with Seventeen. Ultimately, however, Kershaw found writing for others frustrating.

“Ninety per cent of what you do either never gets recorded, or gets recorded but never released,” he says. “Plus, I was getting fed up with having to please so many people: the artist, their manager, the A&R man, then the marketing people and the pluggers.

“It got to the point where I was writing stuff that I didn’t even attempt to send to my publisher, because I thought no one would record it. So the only way to use some of those songs was to record them myself – I ended up with an album.”

The 1999 release of 15 Minutes was not just Kershaw’s first album for a decade, but also prompted his return to live performance. “I didn’t walk on stage at all for about nine years,” he says, “but when the album was about to come out I got offered a festival in Denmark.

“I didn’t have a band, so we held auditions and put some people together and then I thought, well, the band’s together, we might as well do more gigs. I did a little tour of Germany, some gigs over here, and slowly got back on the horse.”

It was around that time that the first 80s revival festivals began to happen.“I was very suspicious about it at first,” Kershaw admits. “I was making new albums and thought it would be kind of giving up. You know: ‘Here’s one

I wrote 30 years ago…’

“But I ended up relenting and in 2004 did a Here And Now tour with Midge Ure, Heaven 17 and Kim Wilde. Apart from anything else, it was a lot of fun and I thought, you know: it’s quite a good thing, fun.

“It’s still a buzz, walking out and hearing people sing those songs back to you. It’s a great atmosphere backstage, too.

“You’re all in it together, you’ve all been through the same stuff and you all can’t believe you’re still getting away with it!”

In fact, as he prepares to embark on the Icons of the 80s tour with Go West and Cutting Crew, he says he’s enjoying performing more now than he did back in the day.

“I’ve always been a bit of a control freak and so much of that time in the 80s was out of my control, and pretty terrifying because of it. Now I’m in complete control of what gigs I do and what I sing and in that respect it’s much more relaxed.

“It doesn’t seem so earth-shatteringly important as it did back then when you were surrounded by so many people whose livelihoods depended on you.”

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!