Simple Minds interview: “We were going to do, regardless of how hip or trendy it was”

By Classic Pop | October 7, 2022

In 2018 Simple Minds returned with their 18th studio album, Walk Between Worlds. That year, we talked to Jim Kerr about how the band had weathered the storm and emerged stronger than ever… By Paul Lester

In 2018 Simple Minds returned with their 18th studio album, Walk Between Worlds. That year, we talked to Jim Kerr about how the band had weathered the storm and emerged stronger than ever… By Paul Lester

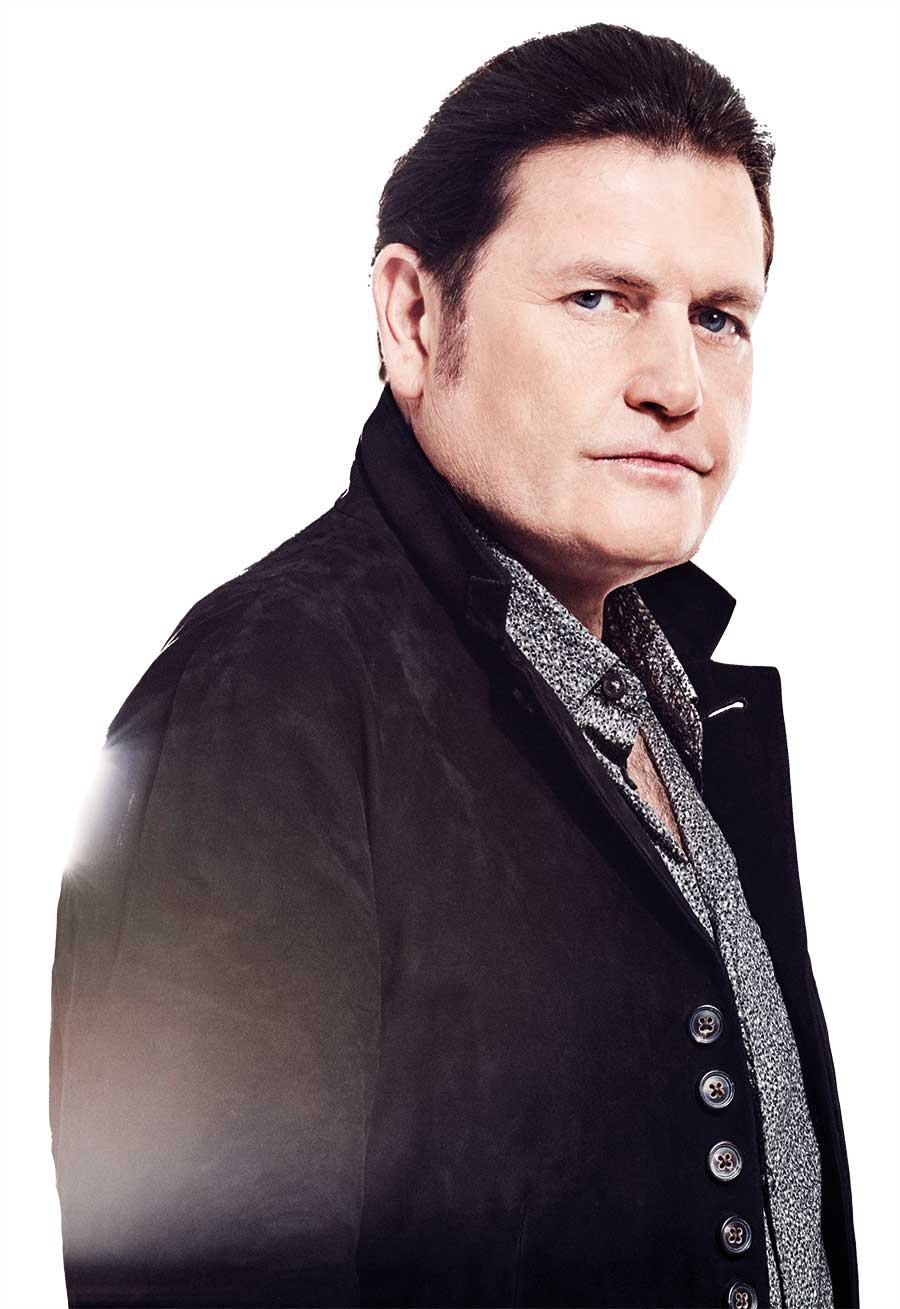

Jim Kerr is sitting in the restaurant of a smart West London hotel, casting back over his band’s glittering 40-year career. But this is the Simple Minds frontman we’re talking to here, so it’s not the cosy longing for a simpler black and white age.

No, he’s being nostalgic for the futuristic pop days of 1980-82: the colourful, expansionist era when everything is possible and his band were travelling around Europe at “30 frames a second”, conjuring Themes For Great Cities, channelling the edgy tumult as they witnessed Berlin in all its bleak magnificence and passed through Paris as places of worship were assailed by explosives.

Working class cultural omnivores from Glasgow’s tenements, they were devouring art and literature and experiencing the vivid thrill of it all, the real cacophony, at first-hand.

“It was music, movies and books,” recalls Kerr, looking every inch the pop star elder statesman in his full-length black coat with fur collar, covering a black t-shirt.

“It was going to Berlin and seeing the Wall, being in Paris when bombs went off in synagogues. It was reading Joseph Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness but seeing tangible stuff as well. We’d left the high-rise building in Glasgow behind. It was an incredibly rich time.”

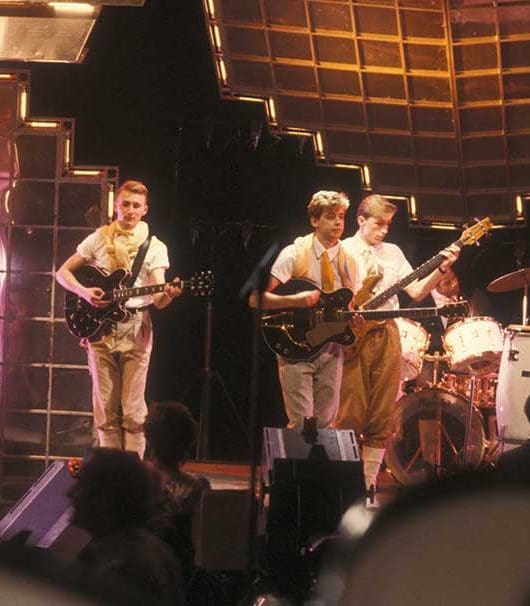

The speed of change was astonishing as Simple Minds released five albums in three years, issuing their debut album, Life In A Day, when Kerr was 19 and their shimmering new pop masterpiece, New Gold Dream (81/82/83/84), when he was barely 23.

“I don’t know how we, and others, did it,” he says of the famously fertile punk and post-punk period. “It shows you the energy we must have had. Where did we find the time? Because we were touring as well as recording an album every 10 months.”

Back then, Simple Minds seemed to be rushing headlong into the future. But they haven’t necessarily slowed down. They are about to release Walk Between Worlds, the follow-up to 2014’s well-received Big Music and the 2016 “reimagining” (Kerr’s word) of their catalogue that was Acoustic.

In fact, Kerr has already come up with four brand new tracks that will form the basis of Simple Minds’ next album.

“I’m rushing into the next album just now,” he says, in his thick Glaswegian brogue. “We’ve got the bit between our teeth. Where that drive to move on comes from, I don’t know. But it’s kind of a characteristic of mine – moving ahead.”

And yet he acknowledges that, as much as he thinks about the future, he is forced to accommodate his past.

“We do have this dance with the past,” he allows. “It’s the past that made us.”

Does this teetering between now and then explain the title of their latest album, Walk Between Worlds? Apparently not: it’s about notions of empathy, explored on the title track.

But the opening number, Magic, does reflect on the qualities Kerr and Co were required to bring when they started the band back in 1977.

“I was thinking about where in God’s name we got the chutzpah, the sheer gall, to even dare to think we had anything of interest to say,” he admits of a time when, really, the only British cities with substantial musical histories were London and Liverpool.

“Glasgow was an utter desert. We’d never met anyone who had written a song. ‘Talented people’ would be your cousin who could play the accordion or draw.”

It was punk that saw the UK music industry become, as Kerr puts it, “decentralised”. The effect on Glasgow could be felt immediately as the seismic movement unleashed a wave of creativity. “Before punk, a band had to go to London [to succeed],” he observes.

“Up until then, no one had done it – no one had a record deal or got a gig. People would have laughed at the idea! Within a year, we had the keys to the asylum. There were people starting record labels or fashion companies, or doing documentaries on krautrock. You didn’t have to be ‘good’, you just had to have ideas and energy.”

Creative hubs

Suddenly, Glasgow – and Edinburgh, and Dundee, and other British hubs such as Manchester, Sheffield, Bristol and Leeds – were full of like-minded creative types. Every week, the music papers would be packed with hot new Scottish bands: Simple Minds, Associates, Orange Juice, Josef K, Fire Engines, Altered Images…

“We were all very much of a kin, and we’d see each other at the same gigs,” says Kerr. “Alan McGee wrote in his book [Creation Stories: Riots, Raves And Running A Label] about going into Glasgow city centre and seeing this group of goth kids: that was me and [Minds guitarist] Charlie Burchill!

“We were all quite different, but we all had a voracious appetite, and a curiosity. I think you’re born a type, and we were lucky enough to be born the types who have the madness to begin with, to believe in magic.”

Simple Minds, like many of their generation, were children of David Bowie and Marc Bolan: “Bolan was John The Baptist, he told you the shape of things to come. Bowie was the Starman.”

One of Kerr’s biggest regrets was not being able to see Bowie in Glasgow on the Ziggy Stardust tour because he – then a 13-year-old butcher’s boy – had stood on a plank of wood with a rusty nail and his parents wouldn’t let him attend on crutches.

But he did catch this glamorous character – “rumoured,” he gasps, still half-believing it, “to be from another planet” – four months later on the Aladdin Sane tour, by which time he had also seen some of his other favourites: Roxy Music, Alice Cooper, and Genesis with Peter Gabriel.

“The world was never the same again,” he says, still in touch with the feeling. “To actually experience them… We became obsessed.”

Hard to believe but, within a few years, Simple Minds had toured as support to Gabriel in Europe while the band and their entourage had sung backing vocals, alongside Bowie, on Iggy Pop’s album Soldier.

At that point, Simple Minds were evolving from a somewhat derivative new wave band into an experimental outfit informed by prog, glam, the nihilistic drone-rock of The Velvet Underground, krautrock, the Euro electronica of Kraftwerk and sequenced disco of Giorgio Moroder.

By the end of 1979, and their second album Real To Real Cacophony – a contemporary of Wire’s 154, Gang Of Four’s Entertainment!, Talking Heads’ Fear Of Music, PiL’s Metal Box and Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures – Simple Minds were becoming serious contenders.

By Empires And Dance (1980), issued the same year as Bowie’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) and Iggy’s Soldier, they were rivalling their heroes. Kerr considers the simultaneously released 1981 sets Sons And Fascination/Sister Feelings Call to be the point where they stumbled upon an original sound.

“Some artists arrive fully-formed: The Patti Smith Group, The Smiths. Other bands take a bit of time,” Kerr decides.

“I still think Real To Real… had a lot of good things, among them imagination and inventiveness, but to me it wasn’t until Sons And Fascination that we took our influences and grew something new.”

And by New Gold Dream (81–82–83–84) they – and many of their peers – had outstripped those influences. “Of course, I would never see it that way,” he argues, “but we had begun to be more our own thing. Everything about New Gold Dream… was – I can’t say ‘perfect’ but it was the perfect record for the time and for us in our career,” he muses.

“It had that quality throughout, there was the artwork, it had hit singles…”

NGD… captured perfectly new pop’s peak, the moment that dour, dark post-punk gave way to bright pop, NME ceded to Smash Hits, Trevor Horn unveiled his hi-tech productions for ABC, Dollar et al, and the charts were suddenly the radical place to be.

“I think the first band wanting to ‘go pop’ was XTC – that’s when Virgin [Simple Minds’ label after their third album] started getting interesting,” he reflects.

“Who could imagine [labelmates] The Human League being pop, let alone us? They went from Being Boiled to being No.1 in the States in, what, two years? Who can imagine Boy George being so big? Then there was Marc Almond and those beautiful songs made out of soul, cabaret and synths…”

Kerr was especially impressed by Billy Mackenzie and Associates, whose Party Fears Two (“This amazing ghostly, haunting pop music”) beat Simple Minds’ Promised You A Miracle to the higher echelons of the singles chart in early 1982. “I remember thinking, wow, they’ve done it before us. The charts were where you wanted to be…”

Breaking America

New Gold Dream might have represented Simple Minds’ creative zenith, but it wasn’t their commercial apogee. It wasn’t enough to be one of the stand-out bands of the new pop era. They wanted to compete with the biggest acts on earth.

“We were a bit fearless – we were going to do what we were going to do, regardless of how hip or trendy it was,” Kerr says. “The idea of becoming a big band was sneered at, as was the idea of trying to break America.”

Kerr talks of “having a sense of destiny”, and of belief. Simple Minds had the latter in spades. But not quite as much as a bunch of upstart Irish rockers. He wasn’t convinced by them at first.

“I wasn’t much into guitar bands, so I resisted U2,” he admits. “Then, when I finally did see them, they blew me away. They seemed so compact – just a vox amp, a tiny drum kit, no banks of synths or sequencers – and yet it was overwhelming.

“People asked me: ‘How did you know they were going to be the biggest band in the world?’ and I’d say: ‘Because they told me’.”

In 1983, it wasn’t clear who was heading for global domination out of U2, Simple Minds and Echo & The Bunnymen. The Steve Lillywhite-produced Sparkle In The Rain (1984), featuring the anthemic Waterfront, rousing Up On The Catwalk and charging Speed Your Love To Me, suggested it might be the Minds. Was it a deliberate move, to go “stadium”?

“It seems cold now, but apart from John Leckie, who produced our first three albums, we changed producers every album,” Kerr surveys his band’s career.

“We felt as though we’d got the max out of Peter Walsh [NGD producer], and we were evolving so fast. Plus, we’d just got in [powerful drummer] Mel Gaynor and we’d done our first few festivals, in Belgium and Holland, in front of 80,000 people, and I remember thinking: ‘What sort of music would work here?’ Six months later we had Waterfront.”

The price of success

Was he as comfortable playing big spaces as he was pubs?

“We were never comfortable with any of it because we’d never done it before. People just assume it’s an easy jump to go from playing up in Aberdeen in front of a bunch of fishermen, to playing universities to playing arenas in Europe… Every gig presented a different challenge.”

Such as the one supporting Peter Gabriel in Turin where the [prog] audience threw missiles, or the one in Marseille where a rioting crowd was dispersed by policemen bearing tear gas.

“That was the time of the Baader-Meinhof gang and anarchists,” he recalls. “Gigs would often be the focus for violence. In places like Italy or South America, there’d be the leftist kids, the right-wing kids… Everyone came.

“When you get bigger you realise your band isn’t yours anymore. I remember playing a stadium in Switzerland and our production guy looked down. I said: ‘Why the long face?’ He grumbled: ‘We need 40,000 people to break even and we only have 38,000.’”

Simple Minds adapted well to the huge success that followed 1985’s Once Upon A Time album and the hit single Don’t You (Forget About Me).

John Lennon described early-Beatles fame in terms of Caligula-esque debauchery. How mad did things get? “Well, I don’t think anyone would have touched The Beatles,” he replies. “And then there were the heavy metal bands…

“On a scale of one to 10, we were probably a five.”

Kerr does recall – much to the discomfort of his press officer, who has joined us – asking his Italian limo driver whether he could purloin for the band: “Some 100 per cent Colombian [cocaine]” and the response was pure Scorsese/Scarface.

“I can get you cocaine, I can get you helicopters, I can get you AK47s…” Kerr remembers turning to Burchill and sighing: “This is the movies.”

Still, Kerr was never in it for the hi-jinks. He frames it in football terms: “Whenever we got wasted, we would be godawful the next night. And we wanted to be on form. We needed to get three points every night. A draw wasn’t good enough.”

Simple Minds were Premier League rockers throughout the 80s, culminating with the Trevor Horn-produced Street Fighting Years (1989).

Things looked set to continue that way in the 90s when Real Life (1991) and Good News From The Next World (1995) both reached No.2. But the next decade-and-a-half saw a series of low-charting albums, and Kerr wondered if the game was up.

“It’s no exaggeration to say that, 10 years ago, the band was flatlining,” he says, forlornly. “I thought: maybe this is it. We agreed we weren’t going to go around like punch-drunk boxers because we didn’t know what else to do.

“And we also agreed we weren’t going to do the nostalgia thing – no disrespect to anybody that does, but we didn’t have to. So we decided if we were going to do it [again], we’d have to commit 100 per cent.”

He admits it wasn’t easy returning to the fray following a lay-off that saw him even investing in a hotel.

“You find out a lot about yourself,” he says, revealingly, “when you’re in a van driving to a half-full club, past a stadium that you once sold out. I guess you either get drunk or depressed, or you ask yourself: ‘What are we in this for anyway?’ Do we want to be a small band, a big band, or are we going to try to get on with being a truly great one?”

Moving on

Does he care about size? He fixes Classic Pop a stare. “If you asked me, would I like to be selling as many records now as we did in the 80s? Guess what my answer would be.”

They might not quite be in the top flight, but Simple Minds are Division One survivors, who can indeed eschew the retro circuit to focus on the new.

Their recent albums have acquitted themselves well: Graffiti Soul (2009) and Big Music (2014) were both acclaimed as returns to form. Walk Between Worlds is poised to do the same. Kerr and Burchill have got Simple Minds back on track.

“Ten years ago it was a bit like putting the wheels back on, getting the engine going, turning the car around and seeing how far we can take it,” says Kerr, who confesses, despite the automobile metaphors, “I don’t even like cars”.

“That,” he adds, “is the best way to describe where we’ve been.”

And where they’re going?… “We’ve moved on,” he says, simply, thinking of the new seven-strong configuration, with Kerr and Burchill the sole original members. We’re still Simple Minds, but if you look at us in 1983, who would have thought it’d come to this? The challenge is to keep doing what you’ve always done, but change.”

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Simple Minds Walk Between Worlds in out now.