First we take Manhattan – the second British Invasion

By Classic Pop | October 1, 2022

How the Second British Invasion took on the American charts and won. By Paul Lester

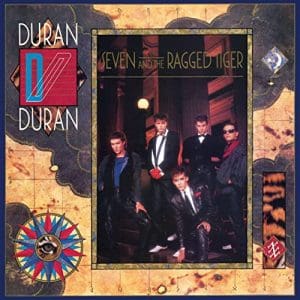

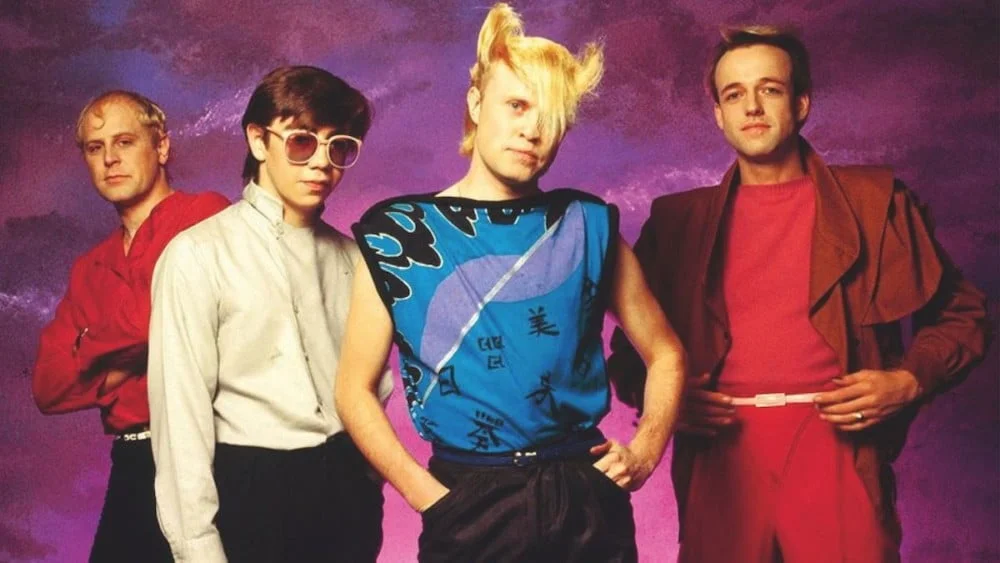

In the UK, we were at the vanguard of a brand new age,” ABC frontman Martin Fry tells Classic Pop, reminiscing about that period in the early-80s when his band and their British new pop and New Romantic peers – The Human League, Culture Club, Duran Duran, Eurythmics, Bananarama, Thompson Twins, Soft Cell – effectively invaded and colonised the US charts.

He wonders how weird they must have seemed to all the REO Speedwagon, Foreigner and Journey fans. “In America,” he decides, “it must have looked as though we’d come from outer space.”

Firm foundations

Britain could see new pop coming: in a way, it was the final, full flowering of punk’s flamboyance and peacock attention-seeking. But the American music scene of the late-70s – when the scruffily hirsute, denim-clad likes of Fleetwood Mac, the Eagles and Boston ruled the waves – hardly prepared them for the pop onslaught from the UK.

If anything, the Disco Sucks movement – exemplified by that fateful day in 1979 when legions of dance music haters gathered in a baseball stadium in Chicago for a ritual burning of disco records – suggested US audiences were unlikely to have fallen for legions of glamorous maquillaged non-musicians (and that was just the boys) preening over synthesizer beats and melodies. And yet they were virtually queuing up to buy our wares.

If anything, the Disco Sucks movement – exemplified by that fateful day in 1979 when legions of dance music haters gathered in a baseball stadium in Chicago for a ritual burning of disco records – suggested US audiences were unlikely to have fallen for legions of glamorous maquillaged non-musicians (and that was just the boys) preening over synthesizer beats and melodies. And yet they were virtually queuing up to buy our wares.

Americans were possibly somewhat primed by David Bowie’s mid-70s forays with the Young Americans album and its singles, the title track and Fame, all obvious precursors of, and key influences on, Fry et al.

That said, the ABC singer, despite loving his “plastic soul” phase (“They should teach it at school”), argues that Bowie was still too much of an esoteric, marginal artist at this point for Young Americans to have impacted on the mainstream.

More likely to have paved the way for Blighty’s new music brigade were the bands and singers, loosely categorised as “new wave” aka punk lite, who started having Stateside hits from early 1979 onwards – acts such as The Police, Elvis Costello, Joe Jackson, The Pretenders and Squeeze.

Even Gary Numan had an unexpected Top 10 entry in the US Billboard Hot 100 with Cars; unexpected because it was a synth-pop song and, after all, America was the land of the authentic blue-collar guitar rocker and the last thing you’d have imagined them lapping up was Numan’s proto-electronic drone.

And yet, joining Cars in the US charts that year were the similarly synthetic Pop Muzik by M and Video Killed The Radio Star by Buggles, the latter the first ever video played on MTV, which launched on 1 August 1981, providing the perfect platform for the new generation of videogenic Brits.

Dawning of a new era

Suddenly, it was all gravity-defying and/or asymmetrical hair, fey posing and neo-operatic crooning, filling the void just as cool new American music was looking rather thin on the ground: it’s probably no coincidence that, of the first 10 videos played on the fledgling TV station, six were by UK acts.

Brit bands had grown used to producing arresting visuals for the likes of Top Of The Pops and The Tube (whereas US ones generally avoided promos, save for the occasional performance-based short).

Brit bands had grown used to producing arresting visuals for the likes of Top Of The Pops and The Tube (whereas US ones generally avoided promos, save for the occasional performance-based short).

Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet and Bowie, on the other hand, rose to the challenge of creating epic, big-budget videos to match their widescreen sonics.

And yet the music still sounded good “un-enhanced”. Luckily, a Los Angeles radio station like KROQ-FM was at hand, becoming MTV’s aural counterpart, greeting with open arms the new music from across the pond.

What began as a trickle became a gush, then a veritable waterfall: in 1983, 30 per cent of US record sales were from British acts.

There was one chart, in mid-July, where 20 of the Top 40 singles, including seven of the Top 10, were by UK artists – this beat the previous record of 14, set in 1965 when The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Hollies, Herman’s Hermits, The Dave Clark Five and others became avatars of the first British Invasion (in fact, two of the latter, The Kinks and The Hollies, were part of that 1983 Top 40, with, respectively, Come Dancing and Stop In The Name Of Love).

The Police, then pretty much the biggest band on the planet, had the best-selling single of 1983 on the Hot 100 with Every Breath You Take, while in April 1984 40 per cent of the Top 100 singles, and in May, 1985 eight of the Top 10, were British.

Breaking and entering

This was the Second Invasion’s imperial phase and well-established acts such as Paul McCartney, Yes, Elton John and Phil Collins benefitted from the popularity of newbies such as Wham!, Duran Duran and Culture Club.

But it wasn’t all electro-pop and futurist cold wave filling the charts and airwaves, however.

There were the soul-inflected sounds of ABC, Spandau Ballet and Dexys Midnight Runners – who, in Martin Fry’s words, were “taking coals to Newcastle” – and the Celtic rock of Big Country and Simple Minds.

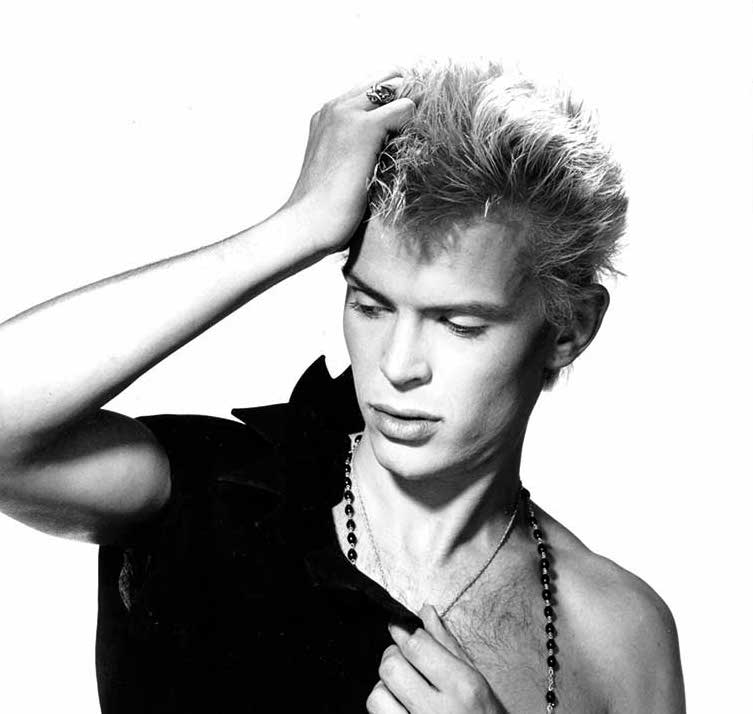

Anything was possible: even a lapsed punk rocker like Billy Idol could reinvent himself as a curled-lip, leather-clad blond Elvis for the MTV generation.

But there was undeniably a cornucopia of keyboard-heavy music, notably US breakthrough synth-pop hits Don’t You Want Me by The Human League and Tainted Love by Soft Cell, the latter spent a record-breaking 43 weeks on the Hot 100.

Such Stateside success was the culmination of new pop’s ambition for mainstream penetration. As Dave Rimmer noted in his book, Like Punk Never Happened: Culture Club And The New Pop, making it in America was paramount.

“Breaking America was what everyone wanted to do,” Rimmer wrote. “Not just for the money, though that was most of it, but also because if you made it in America then you… made it.”

As the book’s title suggests, Boy George’s brigade were one of the era’s biggest stars. George, in his 1995 autobiography Take It Like A Man, remembered one of the main manifestations of the group’s success being the sheer number of lookalikes in the crowd every time they played.

“The clones were out in full force: ‘Boy mania’ had hit the States in a big way. Dreadlocked fans filled the front rows of every gig and lobbies of every hotel.”

Also massive were Duran Duran, bassist John Taylor has recalled scenes of hysteria reminiscent of Beatlemania at a gig in Seattle in front of 18,000 screaming fans.

- Read more: The story of MTV

“It was like somebody had given the entire audience drugs. We couldn’t hear the monitors. We couldn’t hear ourselves play.”

From George to Annie Lennox – who appeared together on the cover of Newsweek, in a story titled ‘Britain rocks America – again’ – androgyny was suddenly acceptable in a nation where, up to that point, Bruce Springsteen had provided the template for the regular male rock performer.

As Fry intimated earlier, some of the new pop stars weren’t so much androgynous as extraterrestrial.

A Flock Of Seagulls – who had huge US hits with I Ran (So Far Away) and Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) – spring to mind here: former hairdresser and frontcreature Mike Score’s alien coiffure was bizarre even by the standards of the day. For one brief shining period, eccentricity and strangeness were in.

“It had a life all its own,” Score says today. He’s right: his band, and hairdo, have had an amazing cultural afterlife, earning allusions and asides in Pulp Fiction, Family Guy, Friends, Austin Powers and The Wedding Singer.

“It’s The One,” he adds. “People say ‘the 80s’ and they immediately think of the Flock Of Seagulls haircut. I was a crazy kid, and I did a crazy haircut, but I’m so glad I did.”

Space age love

A Flock Of Seagulls were one of the first UK acts to recognise the potential of the American market: they came over to tour with Squeeze in 1982 and stayed.

“We were there to open the gates and go: ‘Come on in’,” he tells Classic Pop. “More into sci-fi than songs about loving my baby. Eventually we came up with a strong look and cool, different music and people started to look our way.

“We were there to open the gates and go: ‘Come on in’,” he tells Classic Pop. “More into sci-fi than songs about loving my baby. Eventually we came up with a strong look and cool, different music and people started to look our way.

“We weren’t a raincoat band, dull and dark and dingy,” he adds, thinking of Echo & The Bunnymen and their dark-rock ilk, neatly capturing the shift from post-punk to new pop.

“We didn’t want to be stuck in a corner with a pint of Guinness; we wanted to be colourful, out dancing and having a good time.”

AFOS might have epitomised the shock of the new, but actually their method of breaking the States involved the tried-and-tested route of touring – plus some equally good old-fashioned strong musicianship and teen appeal.

“We were the first of the 80s bands that didn’t just come here to play the big cities,” Score considers. “We got the bug for playing. We ended up staying for a year. Having guitars helped Americans realise that we could rock, while the synths made us seem new.

“Oh, and the girls liked the look, they wanted to dress up like us. We were basically boys in girls clothing.”

Score admits that the band had to overcome initial suspicions. “It was weird because when we first went on and they saw synthesizers at the front of the stage a lot of people were like: ‘What the hell is this?’ and were preparing to boo. But by the end of the set they’d be yelling for more.”

It was a case of, après AFOS, le déluge: by 1983, the hills were alive with the sound of new Brit music. “I’d say so, definitely,” Score agrees. “We made a lot of kids look at what was coming out of England.”

It’s easy as 1–2–3

ABC first came to the States on the back of the stratospheric success they had enjoyed with the Poison Arrow and The Look Of Love singles and The Lexicon Of Love album.

“We’d had a No.1 platinum album and suddenly were thrown into that arena,” Martin Fry recalls. Although it was like starting over, the determination was there. “It was,” he says, “time to conquer America.”

ABC took their “tuxedos and sparkly Lexicon Of Love show” to the US, and immediately appealed to the hiperati – including Andy Warhol, who showed the group round the Factory in New York, and Stevie Wonder, who invited them to his radio station, KJLH, in Los Angeles.

But crucially they didn’t restrict their dates to New York and LA, instead slogging round places like Texas and Phoenix, with mixed results.

“There was one show where we had our 18-piece orchestra onstage with their sparkly tuxes on, and we could hear the sound of heavy metal – that was the band going on after us,” he shudders at the memory.

“Other times, there’d be people still playing pool at the back of the hall while we played. America was like the 16th century when we arrived, culturally – it hadn’t had punk rock to pave the way. It was the dark ages. Bands like Lynyrd Skynyrd…”

Nevertheless, Poison Arrow and The Look Of Love became hits, establishing ABC as firm US favourites, which they remained for the rest of the decade – unlike some of the UK acts, they sustained their Stateside success, doing even better with their third album, 1985’s How To Be A… Zillionaire!, with its attendant singles ((How To Be A) Millionaire, Be Near Me) and cartoon image, all the way up to 1987’s fourth album, Alphabet City, and its singles When Smokey Sings (a No.5 hit that earned ABC a letter of praise from the titular Mr Robinson as well as a place in the Motown museum in Detroit) and The Night You Murdered Love. Fry was right at the epicentre of the Second Invasion hurricane.

Nevertheless, Poison Arrow and The Look Of Love became hits, establishing ABC as firm US favourites, which they remained for the rest of the decade – unlike some of the UK acts, they sustained their Stateside success, doing even better with their third album, 1985’s How To Be A… Zillionaire!, with its attendant singles ((How To Be A) Millionaire, Be Near Me) and cartoon image, all the way up to 1987’s fourth album, Alphabet City, and its singles When Smokey Sings (a No.5 hit that earned ABC a letter of praise from the titular Mr Robinson as well as a place in the Motown museum in Detroit) and The Night You Murdered Love. Fry was right at the epicentre of the Second Invasion hurricane.

“America realised it had missed out on punk and so in the early-80s things really did change,” he asserts. “The Sunset Marquis [hotel] in LA was the watering hole of choice.

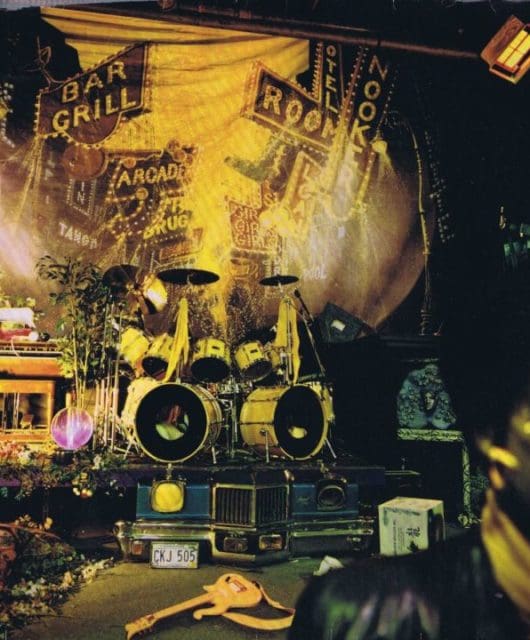

“I saw Prince in the lobby with Wendy [Melvoin] and Lisa [Coleman] while I was eating my peanuts at the bar. And I met David Byrne [of Talking Heads]. Another time I was sitting in a jacuzzi with the guys from Talk Talk. We nodded at each other: ‘Alright, mate, how you doing?’

“Later on, I remember getting on the red-eye to New York and Paddy McAloon [Prefab Sprout] was on the same plane. We started chatting about how excited we were to be going there. I like to think that was the flight he got the idea to write Hey Manhattan! (from 1988’s From Langley Park To Memphis).”

Fry recalls the early Second Invasion days being “sensational”. It was “a different type of fame” to the one back home. US fans of ABC took their ardour to new creative heights.

They even made little puppets of the frontman – “voodoo dolls”, he jokes, miniature effigies of their hero in gold lame – which they would hold up during gigs, so they could “watch” the show. “I thought, ‘That’s strange’,” Fry looks back and laughs.

Fighting for ascendancy

For Mike Score, life on the road in the US involved the usual debauchery: “Nothing I can say too much about without embarrassing somebody,” he admits.

AFOS supported everyone from The Psychedelic Furs, The Go-Go’s and The Police to Duran Duran and The Human League. Back then, the feeling among the Brits was competitive.

“We thought they were a bit snooty, a bit elitist,” he says of the Oakey-fronted Sheffield electronicists. “I’ve met them since and they’re really nice people, but at the time they looked upon us almost as an American band because we had guitars and were on the edge of rock’n’roll. When you’re fighting for success, everybody is the enemy,” he explains.

“But once you’ve been successful, they’re not a threat and you can become friends. Boy George is one of the nicest people you’ll ever meet, and so is Tom Bailey [of Thompson Twins]. I’ve met Martin Fry [on the retro-80s circuit] and he’s a great guy – there’s no bickering or nonsense.”

At the height of their US fame, AFOS were selling hundreds of thousands of copies of their single Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) and Score was being assailed not just by kids but stars as unlikely as Eddie Van Halen of metal monsters Van Halen.

They did one tour, with The Fixx – another UK act who fared well in the States – to arena crowds, culminating in dates at the prestigious Madison Square Garden.

Several decades later, it’s still the same, with cultural props from Quentin Tarantino and Seth MacFarlane and audiences still flocking to see Flock.

“Crazy, isn’t it?” Score says with a Scouse chuckle.“When we first came to America and were successful, we thought: ‘We’re going to party for two years like this’. Now 30-plus years on, we look back and wonder: ‘What did we do that made us what we are today?’

“I’d say it’s good songs, good times, and people that liked our music carrying on doing so. They didn’t leave us behind and go on to something else. I’m delighted.”

Lasting legacy

As for the repercussions of that Second Invasion and its slew of “Limey haircut bands”, as Anglophobe critics used to dismiss them, Martin Fry believes they cannot be overstated. “Britain’s stamp was there,” he attests.

“You can see it in the way Springsteen changed his act in the mid-80s, or the music of Michael Jackson, Madonna and Prince. They were influenced by things coming out of Europe. Prince was into synths and Gary Numan, and Michael got the idea of the cavalry jacket from Adam Ant.

“Steve Barron directed the video for Billie Jean, having done the one for Don’t You Want Me: think about that, and the people they were working with.”

It’s also a matter of record that the then-nascent hip-hop was in thrall to the synthesized sounds emanating from Europe and Britain.

Then it became a two-way affair: The Human League worked with Prince’s old team of Jam & Lewis while ABC hooked up, circa Zillionaire!, with Keith LeBlanc and Doug Wimbish, who played on those seminal early Grandmaster Flash 12-inches.

The British Invasion bands may have been, by the late-80s, usurped by the hair metal hordes although Fry takes some credit for the passing on of the glam baton from his own ostentatious peer group to Motley Crue, Poison, Bon Jovi and the rest as well as by the new dour rockers (R.E.M., Husker Du, Sonic Youth).

And there was pop aplenty from the likes of Debbie Gibson, Tiffany and New Kids On the Block, even if it lacked any of the irony or subversive qualities of the Brit boys and girls.

Still, it was fun while it lasted. There was a gap in the US market for polymorphously perverse pansexual aliens, and it was briefly filled by Oakey, Lennox, Almond and Co.

Or as Fry puts it: “Lunacy and violence and great pop music. They’re every generation’s birthright.”

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!