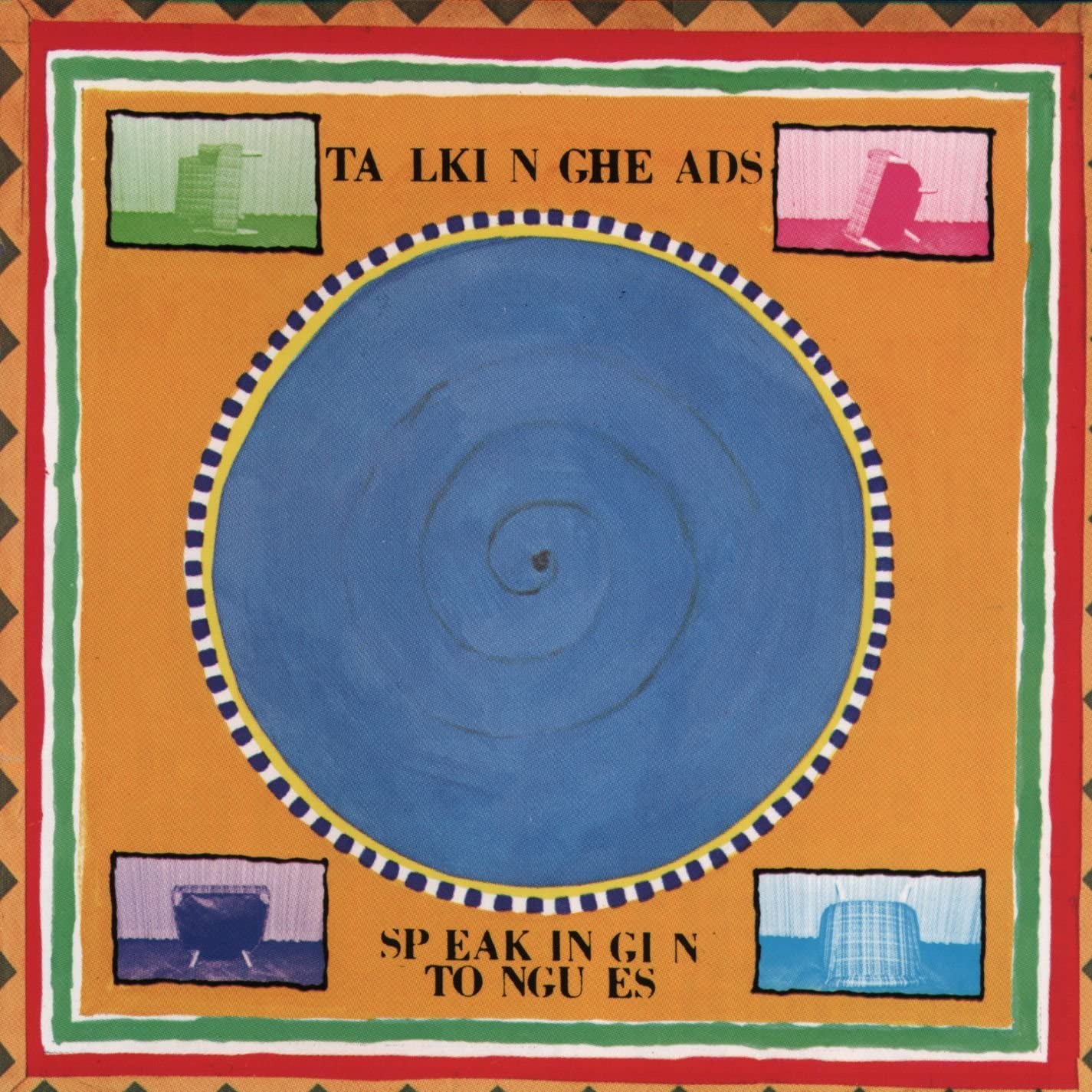

Classic Album: Talking Heads – Speaking In Tongues

By Felix Rowe | January 31, 2023

Talking Heads finally completed their transition to pure funk, and reach commercial peaks with one of their most expansive, fully-realised and danceable records – Speaking In Tongues

Fans of Scooby Doo might recall that classic episode when a fiendishly demonic rock group send all the town’s citizens into a zombie-like, hypnotic trance – all through the power of their incessantly funky grooves.

As the music pumps out of the PA, the crowd’s eyes gloss over, spinning like kaleidoscopes, their toes tapping uncontrollably.

Meanwhile, the bandleader cackles maniacally as the hostage audience are left with no option but to strut their funky stuff.

Listening to Speaking In Tongues, Talking Heads’ insanely funky fifth studio album, evokes the same kind of response.

Willing or not, its nagging, syncopated grooves are engineered to pull your legs onto the dancefloor by some insurmountable, invisible force, like a moth to the flame.

Likewise, frontman David Byrne brings to mind that elusive, shamanic character putting the audience under his devilish spell.

There’s always been something enigmatic, aloof and impenetrable about Byrne that’s key to his appeal. Whatever that something is, it’s particularly prevalent on Speaking In Tongues, an album that’s oblique and surreal, even by Byrne’s standards.

Trying to get the measure of him is like looking at one of those Picasso paintings that portrays the subject from multiple perspectives at once. Even when facing him head on, all is never quite as it seems.

The album’s title references Byrne’s spontaneous lyric-writing process, ad-libbing gobbledegook in real-time to fit the rhythm and meter of the music. It’s an extension of the cut-up, word-collage technique.

Yet in Byrne’s hands, it’s more akin to a religious exorcism – erratic and compulsive utterings spurted out involuntarily, like the stuttering dance moves that accompany them.

Byrne assumes the role of eccentric preacher, delivering his surreal prose like the Sunday sermon, damning the congregation to eternal hellfire.

Talking Heads are, of course, the consummate dance rock band. Having pioneered the crossover from jagged art punk to disco, Speaking In Tongues is the apex of trajectory, finding them at their most groove-oriented and danceable.

Byrne’s theatrics may hog the limelight, but his bandmates – Tina Weymouth, Jerry Harrison and Chris Frantz – prove equally dextrous. The playing is exquisite, with respect due to Weymouth’s seriously funky basslines, locking in with husband Frantz, on drums.

By now, the core quartet had been bolstered by an array of sessioners, amassed over the preceding years, whose presence adds authentic weight to the expanded sound.

Among them, Sly & Robbie cohort Wally Badarou and Parliament-Funkadelic sideman, Bernie Worrell, bring space age synthesizers, while Alex Weir of The Brothers Johnson fame provides suitably slinky guitars.

The album spawned the band’s biggest selling single in opener Burning Down The House. It’s Talking Heads at their most immediate and accessible without blunting any of their sharp edges.

Speaking In Tongues was their first without the guiding hand of Brian Eno, after three records in three years: More Songs About Buildings And Food (1978), Fear Of Music (1979) and Remain In Light (1980).

Following a year’s sabbatical for side projects (Byrne’s collaboration with Eno; Weymouth and Frantz’s new ensemble Tom Tom Club; and Jerry Harrison’s solo The Red And The Black), they returned to the day job, refreshed, and armed with both the confidence and necessary tools to go it alone.

Equally, though, they continued the collaborative spirit, incorporating more musicians into their newly expanded sound.

Sessions took place between July 1982 and February 1983, in several familiar studios, including New York City’s Blank Tape and Sigma Sound, as well as Compass Point, Nassau, where they had previously recorded with Eno and the Tom Tom Club.

The iconic Caribbean studio, owned by Island Records’ boss Chris Blackwell, is where many classic records were made with the house band, the Compass Point All-Stars. This fertile environment spawned some of the finest records of the late 70s and early 80s, from Grace Jones to Robert Palmer.

Talking Heads’ own time at Compass Point was no doubt influential in developing their Afrobeat-inspired polyrhythms (note the nod to Fela Kuti, Fela’s Riff – an unfinished outtake from Remain In Light).

The outside influences have clearly injected new vitality into their groove. Speaking In Tongues sees the collective at their most fluid, whilst being very tight and precise. Earworms abound at every turn. You’re never quite sure what instrument is making what sound. It’s all filtered through Talking Heads’ unique abstract world.

Most tracks extend over five minutes, with the third quarter of each typically reserved for extended wig-outs, allowing the percussion and synth departments to get down and funky.

- Read more: The Lowdown – Talking Heads

There’s an immense amount of sonic variety on display, though operating within a notably limited framework built entirely upon grooves. Where a verse ends and a chorus starts is frankly anyone’s guess.

It’s incredibly skittish and frenetic, steadfastly refusing to stand still at any point – like a toddler that desperately needs to visit the bathroom. It’s so relentlessly bouncy, that at times, the intensity can feel a little exhausting.

Herein lies the album’s Achilles heel. Each track shines brightly on its own. But when played one after another, back to back, the result is one long, endless funk-athon.

Depending on your frame of mind, there comes a point around seven tracks in (or Moon Rocks to be precise) where you wish for just a brief reprieve from the treadmill.

Perhaps a Blackbird or Eleanor Rigby; essentially any discernible shift in gear, a pause in the assault to get your strength back before the final push.

For all its primal, innate funkiness, at times it feels strangely devoid of soul. With Byrne obscured behind characters and oblique lyrics, it’s like he’s using them as a forcefield to protect himself from revealing true feelings or weaknesses. Sure, it’s a thrilling ride, though occasionally projecting an emotional emptiness.

Certainly, at this point in time anyway, Byrne is not one to wear his heart on his sleeve. That’s why the beautifully understated closer, This Must Be The Place (Naïve Melody), comes as such a surprise bolt from the blue.

Only here do you sense Byrne genuinely letting his guard down, daring to share a glimpse of the self, in a subtle but touching way.

“Home, it’s where I wanna be, but I guess I’m already there,” he coos with an aching sense of yearning, before a soaring falsetto that carries no irony. Trading just one of the (excellent) extended funk jams for a little more of this would give the album greater dynamic and emotional depth, elevating it to one of their finest works.

So where does Speaking In Tongues rank within the pecking order of Talking Heads’ catalogue? It’s often viewed as a kind of bridging or consolidating record. It was their highest charting US album, and produced the group’s highest charting US single (Burning Down The House).

Some say that Speaking In Tongues largely did the ‘leg work’ to set up the success of their biggest selling album that followed. It certainly holds its own among their finest work.

When it does show flashes of brilliance, these moments are as life-affirming as anything they’ve produced before or after. Still, it’s not their definitive record in itself.

Modern art thrives on the notion of taking something out of its original context, the extreme example being Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ that repurposed a urinal as a readymade sculpture, much to the horror of the establishment.

Talking Heads were pioneers of this in their own respective field, reframing their subjects, blurring the boundaries, pushing that frontier, while forcing the audience to rethink their preconceived notions.

Without questioning the genuine love and respect Talking Heads clearly display for their influences, their brand of funk is delivered with a certain archness, the raised eyebrow suggesting one step removed.

There is, however, a paradox of perception that if a group plays it totally ‘straight’, it’s inherently naff or lacking authenticity, whereas if played with a subversive knowing wink, it’s somehow more credible and clever.

- Read more: Classic Album – Remain In Light

If it’s a joke or an experiment, then it’s done very well. But once that point has been made, where exactly do you go from there?

Speaking In Tongues is not a radical departure from the frantic polyrhythmic sound developed with Eno, but rather a continuation and refining of it – in many ways the ultimate realisation of their funk evolution.

By the same token, it marks the end of the road in that direction. They’ve gone as far as they can go with that particular line and the experiment has run its course.

It’s telling that they would take a more organic, rootsy route on their next studio album, Little Creatures (1985). Their sixth marked a distinct shift in trajectory and a reinvention of their sound, trading the Afrobeat and space funk for a traditional Americana vibe with complementary instrumentation (steel guitar, accordion and washboard).

To a degree it’s closer to the stripped-back nature of their first album, when Byrne really sings and the band feels looser with more space to live in.

But a final thought on the greatest achievement of Speaking In Tongues is the seminal live film and album it spawned, Stop Making Sense (1984). Far from being mere bonus material to satisfy the completists, it is in fact the much superior record.

Directed by Jonathan Demme, who would later win an Oscar for The Silence Of The Lambs, it is rightly held up as the gold standard of the concert film. It’s a document of a group at the height of their powers as a live act.

It confirms just how tight a unit they were and how thrilling they were to watch, enhanced of course by the fantastic supplementary musicians. (Incidentally, it also serves as an effective exercise workout video too – just try following along to Byrne’s routine for Life During Wartime to burn a few calories.)

It was during their performance of Girlfriend Is Better that Byrne donned his now infamous oversized square suit, which features on the sleeve, and has been much parodied since.

Stop Making Sense includes six of the nine tracks from Speaking In Tongues. Played live, the songs adopt a welcome looseness; a lived-in feel that injects more warmth into them.

Not content with creating one of the greatest concert films ever, Byrne almost topped it in 2020 with the Spike Lee-directed American Utopia, a Broadway performance of his recent stage show.

Featuring three tracks from Speaking In Tongues, it highlights the ongoing resonance of Byrne and Talking Heads’ phenomenal output. Transferred to the live environment, these perplexing songs start making perfect sense.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Talking Heads : Speaking In Tongues – the songs

Burning Down The House

The lead single and their biggest charting hit. A frenetic acoustic guitar riff and ambient sounds build into acoustic funk, with slinky electric guitar and a syncopated synth bassline from Weymouth, topped with the charismatic Byrne vocal, fired out like an aural assault. As is a trademark throughout the album, it features uber cool percussion from a variety of instrumentation, from highly-tuned tom-tom drums to coconuts. It’s very busy and angular, yet also benefits from a fair amount of space between those funky stabs.

Making Flippy Floppy

Talking Heads at their most funky, thanks to a rubbery wah-wah bassline. With a heavy dose of soul, this could be an early hip-hop track from The Sugarhill Gang, inflected with electro-funk. Indeed, it shares some lineage with Prince and the kind of Quincy Jones-produced electro-funk on Thriller et al. Then a really off the wall (no pun) electric guitar solo section comes in, played on an Eastern scale, pushing it in a totally different direction.

Girlfriend Is Better

Opening with a programmed beat, Byrne demands in a strangulated vocal: “Who took the money? Who took the money away?” It’s where the later title ‘Stop Making Sense’ is drawn from. The chorus boasts one of Byrne’s more melodic vocal lines on the record. Squelchy clav sounds and P-funk synths from the Wizard of Woo, Bernie Worrell zing and pop throughout, like Daft Punk battling in a Moog showdown. The groove is vaguely reminiscent of Lakeside’s Fantastic Voyage. In other words, it’s absolutely fantastic.

Slippery People

Still insanely funky, but delivered at a slightly slower pace – it’s not quite slow enough for reggae, but it carries a Caribbean flavour in the calypso-like shuffle. Gospel backing vocals interact with Byrne’s lead in a call and response. The synths are as slippery as the song’s title.

I Get Wild/Wild Gravity

Another slower one, this time it’s all-out dub reggae, complete with jittery rhythms, tonnes of tape echo and a melodic chorus in Byrne’s shouty singing voice. The Compass Point influence is most explicit on this track. I Get Wild provides a welcome drop in pace after the opening assault.

Swamp

A 12/8 shuffle groove recalls The Way You Make Me Feel by Michael Jackson, with one of Byrne’s more idiosyncratic vocals, as he gets into maniacal character. His nasally soul vocal recalls the funk band Cameo, in particular their 1986 hit Word Up.

Moon Rocks

More mileage on the funky groove train. It’s a perfectly competent groove, as good a foundation as anything else on the album. The guitars are especially slinky. That said, it’s more of the same, and the top line is neither catchy nor memorable enough to elevate this above a serviceable but anonymous jam. Give it to De La Soul to rap over and it could be a classic. But at almost six minutes long, it starts to drag a little.

Pull Up the Roots

Another funk groove, not too dissimilar to the last, although this time, Byrne’s top line is much more memorable and melodic, making it more recognisable as Talking Heads. One of the busier tracks on Speaking In Tongues three minutes in, there’s an extended percussion section featuring pitched cowbells that pound out syncopated Afrobeat rhythms.

This Must Be the Place (Naïve Melody)

This timeless classic has gone on to become one of Talking Heads’ most revered tracks, covered by a range of acts, from Arcade Fire to Iron & Wine. On first listen, there may not appear to be much to it, but that’s exactly where its beauty lies. It’s Byrne’s self-professed attempt at a love song, without the associated corny or hackneyed platitudes, and it’s a welcome variation to hear him sing naturally without hiding behind the mask of a caricature. This Must Be The Place proves without doubt that they are more than capable of subtlety and understated moments. While not exactly too little too late, it’s certainly a relief when it arrives.

Two Note Swivel (Unfinished Outtake)

The song’s title gives a pretty good description of what to expect. It’s another extended funk workout. The fact that it’s unfinished is perhaps a saving grace in the degree of space retained in the arrangement.

Burning Down The House (Alternate Version)

This version is just as cool as the ‘definitive’ one that opens the album. Though not radically different, the arrangement is discernibly more laid-back and restrained, featuring a thunderous 808 handclap in the beat, injecting an electro vibe.