The story of ZTT

By Andy Jones | January 31, 2023

Radio bans, terrorists and girls dressed in leather… As record labels go, ZTT was anything but boring. In this feature from the CP archives, we spoke to the major players in the label’s history and discovered how Trevor Horn and his friends took on the world and won… By Andy Jones

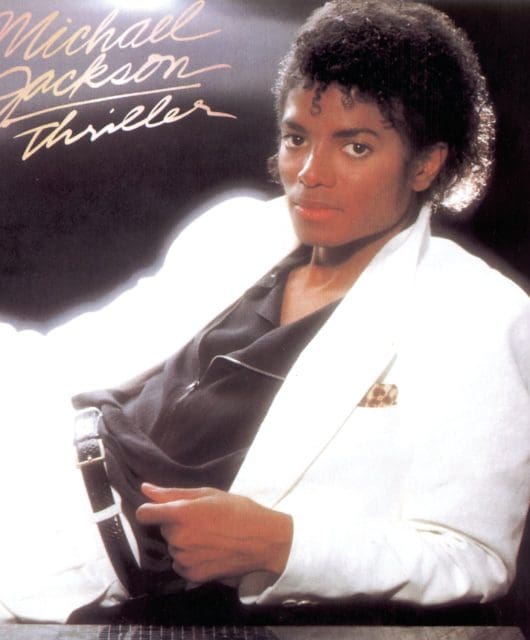

Most of us can remember the first time we heard Relax by Frankie Goes To Hollywood – and the first time we saw that video.

Rarely had anything this sexually charged been seen or heard in the mainstream – and the insinuation was gay sex, remember; something that was still very much taboo in the 80s.

The impact was huge: banned by Radio 1, the single soared to the top of the UK charts, catapulting these five likely lads from Liverpool to worldwide fame.

And suddenly, everyone who was anyone was wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the words “Frankie Say Relax” – and following the release of the band’s follow-up single, Two Tribes, “Frankie Say War! Hide Yourself”.

Representing a band like Frankie was just one of many controversial statements made by the band’s record label, Zang Tuum Tumb (ZTT) – a label whose history reads like a PR executive’s fantasy, but who also made some of the best and most innovative music of the 80s.

In the beginning…

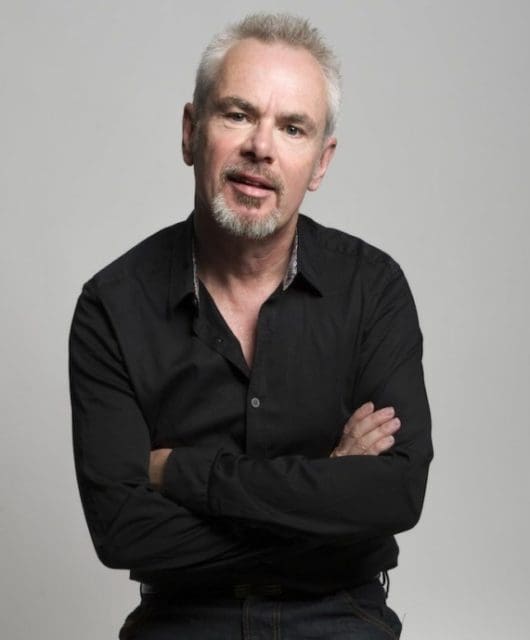

The ZTT story began in the late 70s, when Trevor Horn, frontman with a new band called The Buggles, asked

his girlfriend and manager Jill Sinclair for her opinionon a song that he’d written.

As Sinclair – later Horn’s wife – told The Independent in 1999, “Trevor said, ‘Can I play you a song?’ It was Video Killed The Radio Star, and that’s when I chased him to make the record.”

But before she could persuade him, Chris Blackwell at Island Records also heard the song and persuaded Horn to sign to them instead.

“I lost the deal,” Jill said. But there was a silver lining: “Chris also offered us our own record label because he wanted Trevor.”

So, after Horn had produced ABC’s debut album, The Lexicon Of Love, and stood in as singer on the Yes album, Drama, in 1983 he and Sinclair formed Zang Tuum Tumb (the name comes from a sound poem by the Italian futurist Filippo Tommaso Matrinetti).

Horn would manage the music (he was given a studio, Sarm Studios on London’s Basing Street, as part of the deal with Island), Sinclair would handle the business and NME journalist Paul Morley was drafted in to handle the marketing.

Despite having such a talented team, Horn initially struggled to sign anyone to the label, as his then engineer, Gary Langan, recalls: “I was driving Trevor to a mastering session one afternoon and he said, ‘Oh, God, I need a band to start the label.’ I’d been working with JJ Jeczalik, who was Trevor’s Fairlight programmer.

“We’d been fooling around with a few tracks using the sampler, and had stolen a drum track from a Yes album we were making at the time, which was highly illegal. But I got the cassette out and said, ‘I’ll ’fess up, Trevor – JJ and I have been fooling around with an idea.’ And I played him the demo, which later became Beatbox by Art Of Noise.

“He said, ‘This is amazing. I’m going to give this to Chris Blackwell.’ Chris flew to New York the next weekend and got the demo cassette played at a club. Then he came back and said to Trevor, ‘You have to sign these people to be the first act on your label!’”

And so, Art Of Noise were born. The faceless band would strike a chord both in the UK and, eventually, around the world, with some of the earliest sample-based music, including Moments In Love and Close (To The Edit).

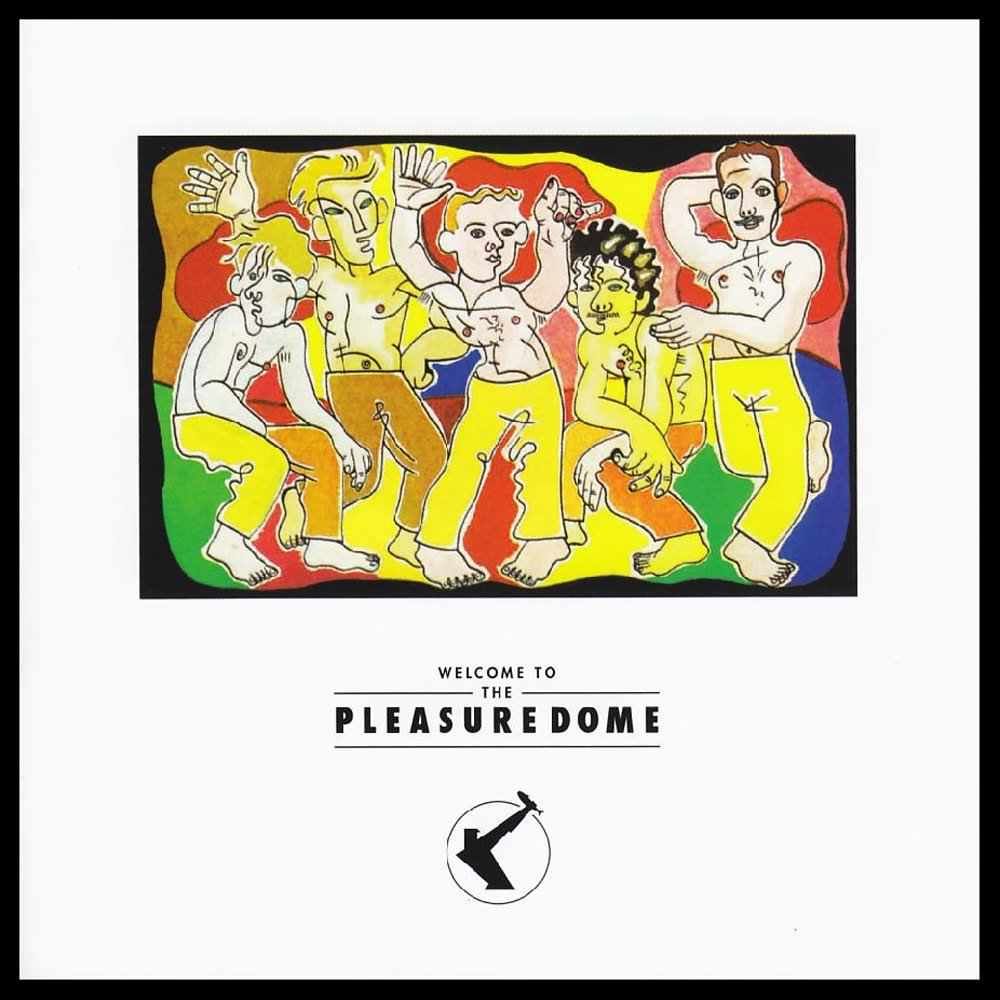

It was the first success for ZTT, and Art Of Noise were soon joined on the label’s books by the German synth-pop band Propaganda. However, ZTT’s defining moment was about to arrive – or should we say come?

And it all started with a chance performance on Channel 4’s cult live-music show, The Tube, that should never have even happened.

“The Tube sent a crew to Liverpool to film another local band, Dead Or Alive,” recalls Frankie Goes To Hollywood bassist Mark O’Toole. “Apparently, when the crew arrived in Liverpool, the band couldn’t be found. But, since they were already there, they thought they may as well film something.

- Read more: Trevor Horn interview

“Somebody put Frankie forward as an up-and-coming band to watch out for, and we found ourselves in a popular club in Liverpool called The State, miming to a demo of Relax that we’d recently recorded ourselves. It ended up on national TV.

“Meanwhile, in Sarm Studios in London, Yes were recording with Trevor Horn. They were taking a break, watching TV, while Trevor was doing his thing in the control room. This video came on of us on The Tube, and they noticed we had two girls dressed in leather gear, complete with whips.

“They went to get Trevor and he loved the video, so our management were contacted by Zang Tuum Tumb. That’s how we got our break: pure luck and lots of hard work.”

Horn took the track Relax and re-recorded it at least four times. He was to become known for his studio perfection and admitted to The Independent in 1999, “I keep going with musicians until everybody is knackered, sick to death and can’t bear to listen to that particular track again. Then I’ll say, ‘OK, let’s start again. I think I know how it should be.’ I’ve got an awful lot of stamina.”

It’s alleged that by the time the track was finally finished, vocalist Holly Johnson was the only member of Frankie Goes To Hollywood to feature on it. Whether that’s true or not is insignificant – it’s what happened next that matters.

Relax was what you might call a slow burner but, thanks in no small part to Paul Morley’s marketing efforts (it’s believed that he was behind those “Frankie Say…” T-shirts), the single slowly climbed into the UK Top 10.

The overt sexuality of both song and video helped, of course – something that came from the band themselves, as opposed to being manufactured.

As Langan recalls, “If you saw the original footage of Frankie on The Tube, it was totally outrageous. The whole outrageousness of the band was totally from them.”

It was this outrageousness that led Radio 1 DJ Mike Read to ban Relax from his breakfast show. A slight over-reaction, perhaps, but this was the 80s and everyone and everything over-reacted back then. Hair over-reacted to cream, and just look at the fuss made when JR Ewing got shot on Dallas. Just imagine how much traffic that would’ve generated had we had Twitter in those days!

The kids reacted against Read’s perceived fuddy-duddy stance and propelled the track to No.1. And the band’s subsequent singles, Two Tribes and The Power Of Love also hit the top spot.

“Frankie Goes To Hollywood made Zang Tuum Tumb,” insists Mark O’Toole. “It was never the other way around. Trevor Horn was huge in helping Frankie become what they were but, by the same token, if you took Frankie away from the label, Zang Tuum Tumb would be no different to any other independent label at the time. Zang Tuum Tumb became known because of Frankie Goes To Hollywood.”

“Frankie were the biggest band in the world for a moment,” agrees Richard Green, a current BBC radio DJ, less given to random acts of banning. “Everyone wanted a piece of them and Relax has to be one of the iconic songs of the generation, especially with the folklore that developed following the ban saga.”

Green acknowledges that Frankie’s success should partly be credited to the marketing machine that sprung up around the band at the time.

“There was the more commercial side with Frankie Goes To Hollywood,” he says. “I still marvel at how Paul Morley’s imagery and Trevor Horn’s infinite remixes persuaded us to buy yet another 12” single, as well as the 7” and the album. The imagery, the wall of sound and the arrogance simply flooded through.”

After Frankie

Having got a taste for success, Horn wanted more and began to develop the ZTT label. “Yes, there was a plan,” Langan says.

“Trevor wanted to recreate another Tamla Motown scenario. In other words, within the first four bars of a record, you knew it was a Trevor Horn/Zang Tuum Tumb production.

“That was the whole ethos at Zang Tuum Tumb. It had a really high branding factor to it, in as much as it was style over content – unlike other labels, which didn’t focus on things like that.”

And with the right people in place, the label enjoyed many more years of success.

Propaganda scored record sales across the world (including a No.1 single in Argentina!), Grace Jones released one of the most iconic albums of the 80s in Slave To The Ryhthm and, later, artists such as Seal and Manchester electro wizards 808 State continued the label’s musical legacy.

It couldn’t last, of course. Frankie Goes To Hollywood were never going to be the kind of band to tour into their 60s, Rolling Stones style, and imploded following disappointing sales of their second album, Liverpool.

Meanwhile, Art Of Noise split acrimoniously, reportedly over creative differences.

Langan prefers to remember the good times, however; times when it seemed like it was Zang Tuum Tumb against the world. When asked what it was that set the label apart from their rivals, he doesn’t hesitate.

“What they set out to achieve was great innovation and thinking,” he says. “They were always thinking outside the box and doing things confidently that other people weren’t doing at that time.

“It’s like all the wonderful things in life: sometimes, you have some great cogs in a gear but they don’t all fit in. But what happened with Zang Tuum Tumb was one of these great situations where every cog just fitted together. It was wonderfully creative. A fantastic time.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!