The Art Of Noise remember In Visible Silence

By Ian Peel | February 17, 2023

In 2016, The Art Of Noise celebrated the 30th anniversary of the platinum-selling In Visible Silence. That year, the group’s core trio of Anne Dudley, JJ Jeczalik and Gary Langan talked Classic Pop through the highs and lows of working with Tom Jones and Duane Eddy, as well as the highs and lows of working with each other, to produce the acclaimed ‘China Trilogy’…

“It was under a real thunderclap,” Gary Langan recounts of the moment The Art of Noise left ZTT Records – after hit single Close (to the Edit) and breakthrough album Who’s Afraid – the night before their first gig was set to take place.

“It was so rock’n’roll. To literally just walk out after dinner, and tell everyone, ‘you might as well go home, because we’re not coming back’. They thought we were joking!”

But they weren’t, and Gary – along with co-founders Anne Dudley and JJ Jeczalik – split not only with their label but with Trevor Horn and Paul Morley who had helped steer the sound and image of a group which, more than three decades later, is still name-checked by everyone from Daft Punk to Drake.

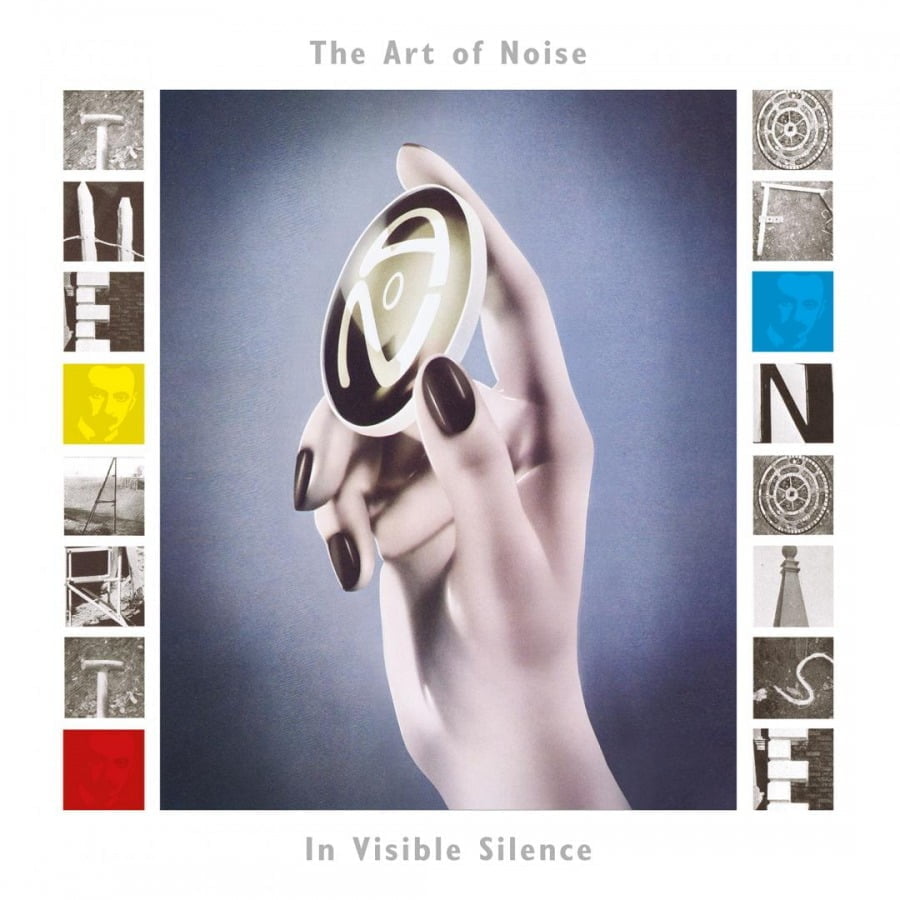

One of the key albums that these artists refer back to after all this time is In Visible Silence, the first that Anne, JJ and Gary made as a trio for the China Records label in 1986.

Expanded and reissued this summer, the trio have reformed to put together a special live show, and to curate deluxe editions of the rest of ‘The China Trilogy’: 1987’s non-stop soundscape In No Sense? Nonsense! and 1989’s parting shot, Below The Waste.

FORCE TO BE RECKONED WITH

But back to the beginning and those first months, post-ZTT. What was the mood like as they struck out on their own? “I think we felt very positive,” Anne recalls. “We wanted to do something that was a little bit more polished than the stuff we’d done for ZTT.

“I’ve always considered those tracks to be demos, I’m not sure we really ever quite finished them. So we wanted to do something with a bit more variety and, yes, to prove that we were a force to be reckoned with.”

“For me, I would say that it was business as usual,” JJ offers, “because it never really occurred to me that we were doing it without Trevor and Paul by virtue of the fact that the recording process generally always started with Gary and I sitting in the studio knocking around a few ideas, with loads of sounds and just throwing them together.”

Gary agrees, remembering that the tracks on In Visible Silence “came about with us fooling around with rhythms that we could discover in everyday life, whether it was spoken word, or a machine, or whatever. That has always been the inspiration for Art of Noise: finding rhythms in some part of real life.

“Sometimes it might just be a drum kick, which it is in places on In Visible Silence, but there are also tracks where it’s even just voices and we’d made a rhythm out of that.”

The spoken word track question is the album’s opener, Opus 4, still one of Gary’s favourites to this day.

“I always thought it was such a clever track. It’s got so much going for it. It draws on the whole rhythm thing and it’s got beautiful melodies from Anne. And it comes from a great poem, November by Thomas Hood.”

And JJ’s favourite track on the album? “Instruments of Darkness. I absolutely loved that, and I still do. Listening to it, and re-analysing it, it stands up as a tremendous piece of work. It’s very, very atmospheric, like the machine gun for the rhythm section and the political speech samples.”

GUNNING FOR A HIT

The most well-known track on In Visible Silence won the group a Grammy: their sample-a-delic cover version of the theme tune to the 50s detective series Peter Gunn, featuring the twangy guitar of Duane Eddy.

“It had all of the right ingredients for us,” Anne remembers, “it was a very simple riff, it was very up. It has a great spirit to it.”

And it worked: the single reached No.8 in the UK and No.2 on the Billboard dance chart and has since been reworked by artists ranging from Pet Shop Boys to Pop Will Eat Itself. But did they know it would be a hit when they recorded it?

“Well Peter Gunn had already been a hit”, Gary points out. “So, unless we really messed it up somehow, we couldn’t really fail… It was written by some geezer that was pretty good (a certain Henry Mancini), it was played by some geezer that was pretty good. You’d have to go some way to cock that one up!”

JJ, on the other hand, puts the success of Duane’s finished guitar track down to his bandmate.

“Duane was very pleased to arrive at the session and see that Gary had assembled a whole load of valve amps and vintage microphones,” he recalls. “And I think I’m right in suggesting that one of the first sessions that Gary ever did as a young tape op was making tea for Duane Eddy.

“So those two factors relaxed him a great deal and he settled into getting the track. And as per my edit on the 12” mix with the “do you think that I should do one more?” sample, we rattled through it really quickly – it was pretty much one take.”

WELCOME, MATT

With Peter Gunn an international hit but with In Visible Silence already finished and released, another single was needed so the group came up with an even more surprising collaboration.

They contacted actor Matt Frewer to reprise his role as computer-generated start-up/upstart Max Headroom and reached the Top 10 again, this time with Paranoimia.

“That track always had a smile on its face,” Gary says fondly. But where did the title come from? “We were sampling and got some girls to each say a word about what they thought the Art of Noise was.

“And one of them came up with paranoid, which somehow turned into paranoimia. We also used them saying ‘the Art of Noise is paranoid’ and ‘the Art of Noise is weird’ for a B-side to Peter Gunn called Something Always Happens.”

That B-side was to be the last track released by the group as a trio as Gary jumped ship soon after for a production career spanning the rest of the 80s (Spandau Ballet, Public Image Ltd.), 90s (James, My Life Story) to the present day.

As a duo, Anne and JJ defied expectations by diving headlong into AoN’s most prolific period and delivering what many – including former collaborator Paul Morley – have acclaimed as one of their pivotal works, 1987’s In No Sense? Nonsense!.

Though it added their theme for Dragnet, the Tom Hanks/Dan Aykroyd caper, In No Sense? didn’t yield any singles so remains somewhat of a lost treasure. “I think it’s quite a complex album,” Anne says, looking back. “It’s sophisticated, and quite musically varied and clever. It just didn’t lend itself to having any singles.”

But it’s full of gems. JJ’s highlight? “A Day at the Races. It was recorded pretty much live to half-inch tape. The rhythm of that looping, galloping sample, I’ve always loved that. In fact that track, along with Instruments of Darkness defined the use of abstruse sounds or colours to create rhythm.

“I think Opus for Four from In No Sense? Nonsense! works well, too, though for completely different reasons, but it was that same principle. I remember when I first heard that echo on A Day at the Races, I was just amazed.”

ADVENTURES IN ADVERTISING

This year’s deluxe edition of this mysterious album unearthed a mountain of previously unreleased tracks.

“We were working a lot at that time,” Anne explains. “We were asked to do a lot of TV stuff (including themes for The Krypton Factor and The Max Headroom Show and a great, lost soundtrack for BBC2’s The Case for Sherlock Holmes) plus adverts (the most fondly recalled being for Tuborg larger in which a version of Legs soundtracked Tim Pope’s first ever commercial noted for its £300,000 budget and nine-day shoot).

“These adverts generated other tracks, they would evolve, and we’d agree that they were good ideas. It was a great period because we were meeting new people, doing adverts and films and things. There was lots of new input.”

As all these new inputs snowballed, Anne and JJ came up with by far their most well-known collaboration, a cover of Prince’s Kiss with Tom Jones.

“We were watching The Last Resort show with Jonathan Ross, this was probably around 1988,” says Anne. “It was a must-watch TV show at the time, and Tom Jones came on. At that stage he was a bit washed up and only did cabaret in Las Vegas, that kind of thing.

“He hadn’t had any hits for a long time. But he looked great and was dressed in black leather, and sang a version of Kiss. And I thought, wow, there’s a thing: he’s very hip, he knows Prince, who was very now at that time, and it sounded great.

“We talked with Tom’s management – I don’t think he even had a record deal at the time – but he was happy to do it. He thought it would be great to work with the ‘high-tech youngsters’ who were The Art of Noise!”

REIGNITING ‘JONES THE VOICE’

The single was a masterstroke, reached No.5 in the UK and reignited Tom’s career. But did it also take The Art of Noise, in its current incarnation, to its logical conclusion?

“I think Kiss proved the theory of quantum physics,” JJ observes rather whimsically, “that every action has an equal opposite. In other words, Tom’s career rebooted and ours exploded…”

Below The Waste appeared at the very end of the 80s and sounded, in some respects, like the group’s Let It Be what with its intentional returns to musical roots (in this case a flashback to Duck Rock with Yebo) and audible demarcations between tracks by each member.

Catwalk (a version of which was also recorded with Jean Paul Gaultier on lead vocals), for example, pointed the way to JJ’s later dance tracks as Art of Silence. While Promenade 1, 2 and Finale signalled Anne’s increasing enthusiasm for orchestral work which has led to, most recently, soundtracks for Poldark and Paul Verhoeven’s Elle.

“It was initially supposed to be an exploration of music of the Southern Hemisphere – hence ‘Below The Waist’ – with lots of interesting collaborations,” Anne remembers.

“But then another idea came up that it should be like Pictures At An Exhibition, referencing Mussorgsky, hence the Promenades. We were working more in isolation, to an extent, by that time. Both just working in very different ways.”

As a result, Below The Waste proved to JJ that the ideal number of members of any group wasn’t two, but three: “The balance of inputs and ideas – and the concept of someone saying ‘no, that’s terrible’ or someone else saying ‘I love that’ – is really at its best in a three-way interaction. When we were working as a trio it was inherently more stable.”

It’s a realisation that brings the story of The Art of Noise’s China Trilogy full circle.

“If you think of a stool and sitting on it, it’s inherently unstable to have a bi-pod. You need three legs or even four to make it stable. The third leg – or third person in a group – brings together any disparate elements that are going on.

“When we were at our best, was when that process was working well. When Anne and I ended up together, it still worked and was still successful but I think what we missed was Gary being that third person. It both unbalanced it, and rebalanced it.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!