No smoke without fire: The 80s rebirth of David Bowie

By Andy Price | February 3, 2023

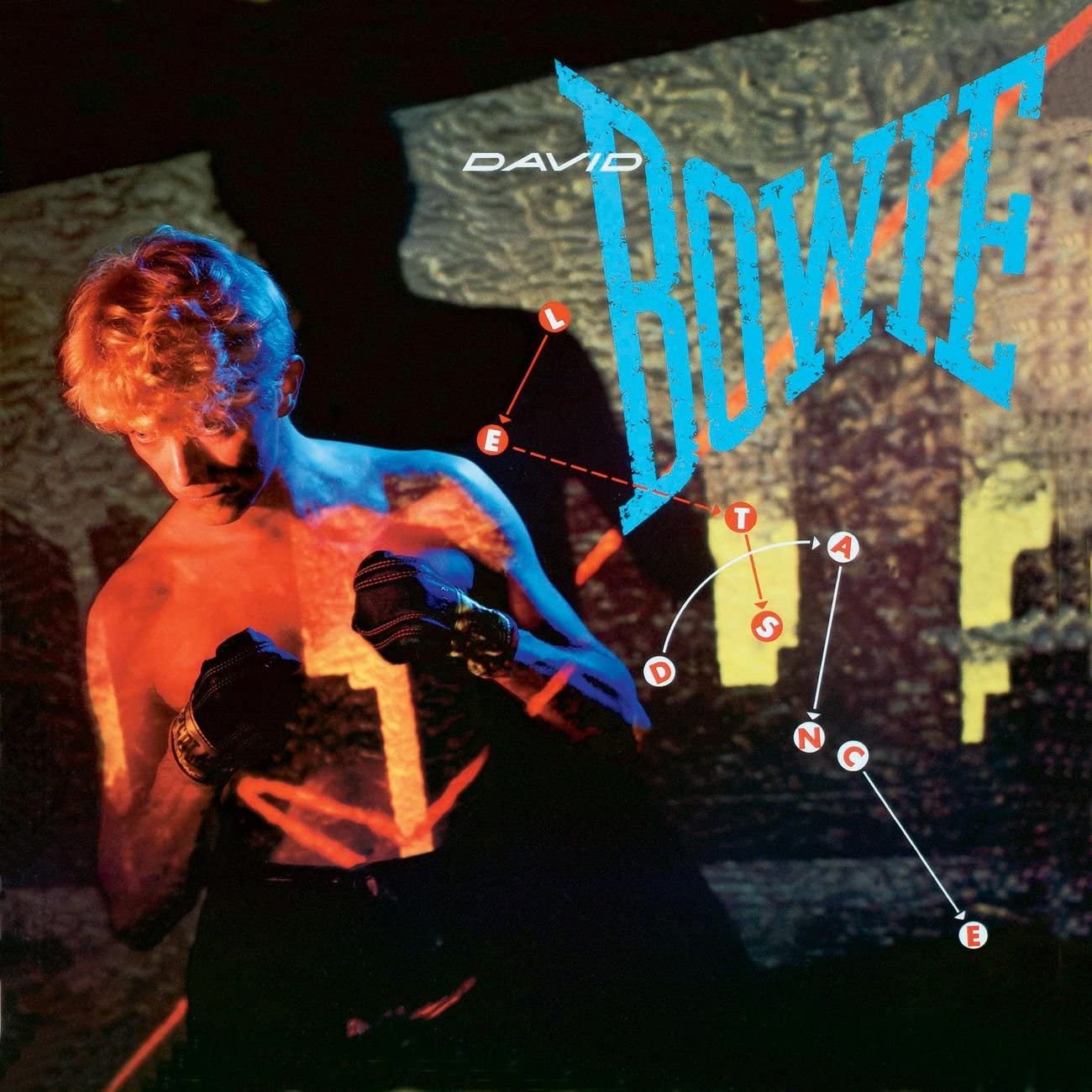

After a few years out of the spotlight, a bleached-blond Bowie returned in 1983 with Let’s Dance and achieved greater global fame than ever before. Classic Pop charts the moment David Bowie ascended to superstardom…

It’s a commonly held critical view that David Bowie’s work was a hugely influential force in shaping the musical landscape of the 1970s.

From the epochal Ziggy Stardust era, to his fearless adoption of Philly soul and his trailblazing experimentation in Berlin during the later half of the decade: Bowie had demonstrated a fearlessness towards music-making that almost single-handedly dictated the musical and social trends of the decade – and left many of his contemporaries floundering.

With 1980’s Scary Monsters, he tied a neat ribbon over his 70s canon by thematically and musically revisiting key facets of his past while also looking ahead to the future. Ever surprising, his next move was perhaps the most unpredictable of them all.

For a multitude of reasons (chiefly, perhaps, his high-profile signing to EMI Records for an estimated $17.5 million), David Bowie decided that the next stage of his career required some bona-fide hits. Despite being an artist of overwhelming significance, Bowie had only really accumulated a small cluster of successful singles.

As the 80s dawned and status was seemingly measured more and more against chart placements, Bowie realised that he’d have to reposition himself in the landscape of pop music yet again.

Clearly feeling that his go-to producer Tony Visconti wasn’t perhaps the best choice to help him achieve this vision, Bowie sought out Chic’s Nile Rodgers to produce an uptempo, funky and accessible album.

“We met at his Manhattan apartment, where he showed me a picture of Little Richard in a red Cadillac,” Rodgers told Pitchfork magazine in 2016.

“He said: ‘I want my album to sound like this’. He just had to show me a picture, and I completely understood. He wanted something that felt like the future but was rooted in rock‘n’roll, something soulful, Black, and R&B, but morphed and evergreen. And that’s what Let’s Dance is.”

Visconti was hurt by Bowie’s rejection and – despite helping David with some of the sound for the UK dates of his later Serious Moonlight Tour – became estranged from Bowie until the late 90s.

Bowie spent time developing ideas for the record before bringing them to New York’s Power Station Studios. Along for the ride was a young Stevie Ray Vaughan – the startling, fiery blues guitarist whom Bowie had seen perform at the Montreux Jazz Festival.

Bowie was astonished by the Texan’s skill, and thought he’d be a valuable asset to utilise in the production of his biggest pop statement to date.

“To tell you the truth, I wasn’t very familiar with David’s music when he asked me to play on the sessions,” Stevie Ray later said in an interview with Guitar World, but his virtuosic solos became a standout aspect of Let’s Dance’s sound, particularly on the title track.

His work on the record helped him to further develop his own career as a world-class guitarist, before his untimely death in 1990.

Also joining Bowie’s entourage at this point were the rock-solid duo of Omar Hakim on drums and Carmine Rojas providing the impactful bass. Carmine remembered that the recording of Let’s Dance was an incredibly fun experience.

“Being creative with David was great,” Carmine tells Classic Pop. “For the song Ricochet, which is a great song, he wanted like a Polynesian kind of sound to it. As a Puerto Rican coming from Brooklyn, I was a little bit perplexed by it at first. There were no smartphones then, we couldn’t just Google it to figure out exactly what he meant. So we had to really get into the feel of the track and kind of make our own version of it.”

Indeed, Rojas has nothing but positive memories of working with David on his biggest-ever record and tour. “Let’s Dance for me was a great experience,” he explains. “It was all pretty free, really, in terms of what we could do. Very little cues in the studio to tell us what we couldn’t do; we were encouraged to play.”

Put On Your Red Shoes

The title track of the album – which of course, would become a global smash hit – was conceived as a slightly different beast to how it ended up, originally being arranged as a smaller-scale track with a folkier leaning.

Rodgers recalled in an interview with Billboard that after seriously “funking the song up”, the stage was set to deliver Bowie the commercial success he craved: “It was the first indication of what we could do together as I took his ‘folk song’ and arranged it into something that the entire world would soon be dancing to and seemingly has not stopped dancing to for the last 35 years!” Nile said. “It became the blueprint not only for Let’s Dance the song, but for the entire album as well.”

Recording at the Power Station with Rodgers did indeed yield Bowie the commercial success he’d been hoping for.

The three-pronged chart assault of the record’s singles: the infectious, uptempo Modern Love, a gorgeous, reworked version of Iggy Pop’s China Girl and of course, the ubiquitous (and highly danceable) title track became the biggest-selling of Bowie’s career, with the bank-balance boon undoubtedly bringing smiles to the faces of his new friends at EMI.

Yet despite his success, the superficial nature of many of the record’s lyrics, the obvious commercial sheen of the music and Bowie’s more outgoing, affable personality in interviews and television appearances left many of the more avant-garde members of his fanbase cold.

Bowie himself was, at the time, satisfied with his re-defined status as a pop supremo: “I think the music I’m writing at the moment is probably going to reach a newer audience for me, but if I’m going to reach a new audience then I’m going to try and reach them with something to say, which is on a very obvious and simplistic level.”

- Read more: David Bowie in the 90s

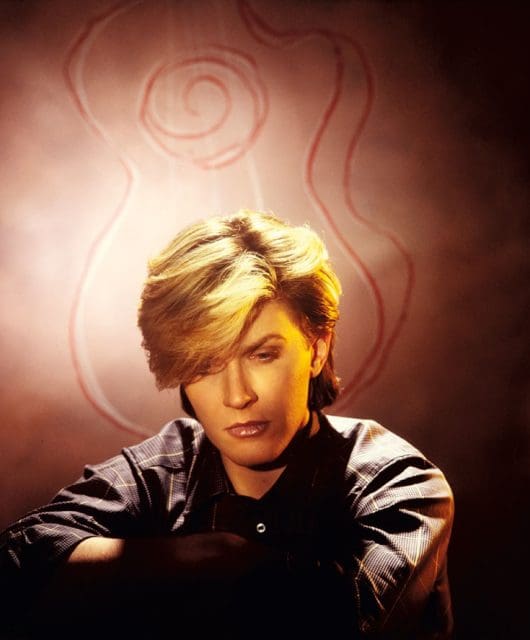

Bowie’s new look and attitude was unveiled at an infamous press conference at Claridges on 17 March. For many devotees, it was a strange and uncanny thing to behold. Gone was any semblance of androgyny, the angular, emaciated look of the mid 70s or the brooding intensity of his personas from later in the decade.

Instead, what we had was a peculiarly plastic version of David Bowie: accessible, conversational and resplendent with a sharp suit, suntanned skin and bleached blond hair. He somehow seemed to embody the decade’s excesses.

In the view of David Buckley, in his excellent Bowie biography, Strange Fascination, Bowie “looked weird – like a Bowie clone. The new corporate skin made Bowie look businesslike and harsh. For the first time, he looked aristocratic, a member of the jet set. It was a difficult image for his fans to even like, let alone want to copy.”

His new – definitively ‘straight’ – persona alienated devotees, particularly those who felt kinship or admiration for the LGBT impact of his work.

He told Rolling Stone’s Kurt Loder that: “The biggest mistake I ever made,” he said one night after a couple of cans of lager, “was telling that Melody Maker writer that I was bisexual. Christ, I was so young then. I was experimenting…”

It was an admission that many felt was a betrayal of the queer nature of much of his art. Let’s Dance-era Bowie openly laughed at Ziggy, too, saying (in the same interview): “I was so fed up with him… But I dragged it out last year and had a look, and I thought: ‘This is a funny film! This boy used to dress like that for a living? My God, this is funny! Incredible! Wait till my son sees this!’”

As shocking as Bowie’s new attitudes were, Buckley noted that the 1983 version of Bowie seemed to have manifested from a desire to “allow himself to enter into someone else’s vision of what a sensible, mature David Bowie should look like.

“Behind the suntan and smiles he looked as frozen and plastic as ever before. The new mask of ‘normality’ was the most extreme artifice of his career.”

Turn The Holy Pictures…

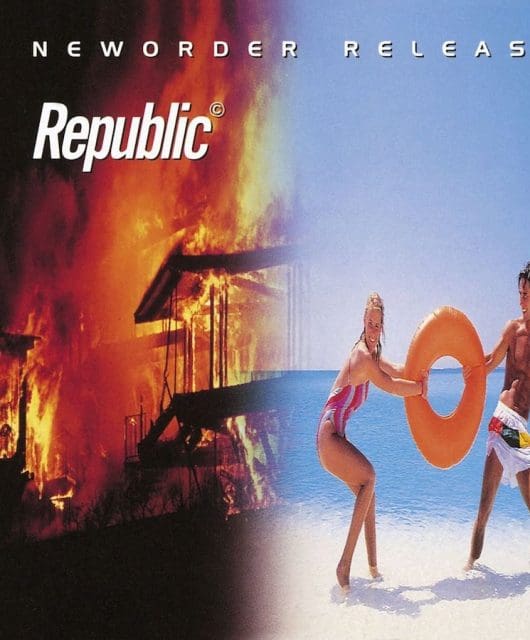

Despite Bowie’s huge shift in attitude in the early 1980s, the resulting record did the job it set out to do, and became a global smash hit. Yet critical divisions do vary quite dramatically to this day. This critical duel began almost as soon as the record was released.

Some critics, such as Jay Cocks in Time magazine, found the record an utter delight, saying the LP was “unabashedly commercial, melodically alliterative and lyrically smart at the same time”, while on the other side of the fence, Dave Henderson of Sounds Magazine said: “Bowie could have put a bit more effort into this miserable, ramshackle affair. The voice is fine, but it’s lazy, emotionless and twee.

“Bearing that in mind, it’s absolutely dynamic compared to the tedium of the arrangements and the terribly predictable playing. Don’t be surprised if Mark Knopfler plays on the next LP.”

In the view of Starman biographer Paul Trynka, Let’s Dance achieved Bowie’s objective: ultimately making Let’s Dance a successful project, though not one we should so readily compare with the rest of his oeuvre.

“The clichéd response is to say that Let’s Dance isn’t a great album. I’d say the jury’s still out, but the fact remains that it’s a great ‘80s’ album. It’s exciting and vital, despite the filler tracks. It’s unfair to compare it to something like Low – it’s like comparing Harry Potter with Franz Kafka!”

Despite the deliberately watered-down version of Bowie we found on the record, his David Mallett-directed videos continued to push boundaries, with the title track’s Australian-set video in particular highlighting the hypocrisy of global capitalism on indigenous Australians, and containing some fascinating imagery – though the cheesy, slow-mo shots of Bowie miming to the Stevie Ray Vaughan guitar solo date the video tremendously.

The release of Let’s Dance dovetailed nicely with the advent of MTV, and Bowie’s new globally accessible, beach-blond persona was a perfect fit for the video age, with his promos in heavy rotation. The channel served as many a young soon-to-be-fan’s introduction to the world of Bowie.

Though debate often rages regarding the record’s merits, today Bowie’s Let’s Dance era is generally regarded as a fun, positive time – though it heralded a gradual decline in artistic quality that Bowie didn’t really combat until the early part of the following decade.

Nile Rodgers recalled in an interview with Pitchfork that, despite the project’s commercial sheen, making the record was an innovative experience: “I looked at it like an art project: the conflict of David Bowie making a commercial record is in itself an arty, cool thing, like, ‘Wow, that’s fun’. Hence my riff on China Girl, which I thought I was going to get fired over because it’s so corny.

“But he heard it and went, ‘That’s amazing!’ I was like: ‘Do you really mean it?’ And he’s like: ‘That’s genius’. You have to see that this is a very special man. This is not your average artist.”

The resulting world tour of the album – dubbed the Serious Moonlight Tour – was Bowie’s first in five years and was an audacious, grand affair that saw him not only performing his recent material, but a selection of his classic tracks (including some Berlin-era material) sheened-up and sounding not out of place in a set that included such uncomplicated exuberance as Modern Love.

The staggering undertaking saw 98 shows performed over four continents and played to around 2.5 million fans.

The Power to Charm

Despite taking a break from the recording of Let’s Dance, the ever-enthused Carlos Alomar returned to take up core rhythm-guitar duties on the tour, and while initial plans were for Stevie Ray Vaughan to join the live band on lead guitar, circumstances dictated that Bowie stalwart Earl Slick took up the mantle, with the bass supplied by the increasingly integral Carmine Rojas.

Carmine told us that: “It was a really sad thing really, it was working okay at first, though there were a lot of older songs that Stevie couldn’t get his head around. If you look at David’s catalogue, there’s some crazy stuff, musically. They weren’t really like your typical blues arrangements or anything like that.”

Other accounts underline Vaughan’s annoyance with the level of choreography required, but the truth of the matter appears to be that Vaughan was replaced due to issues with his management.

On the eve of the tour, SRV’s manager attempted to do a last-minute renegotiation of his fee, without the guitarist’s knowledge. Instead, Bowie’s promoter called their bluff and made the decision to replace Stevie Ray with Slick.

The tour began in Brussels in May 1983 and ran right through to December, taking in the UK (including the Hammersmith Apollo) the USA, Europe and Asia. Bowie made sure he was in peak physical fitness to endure the tour’s stresses.

Cutting out drugs completely (and demanding that no one else on the crew indulged either), Bowie’s early morning routine of shadow boxing and aerobics guaranteed that he was athletic enough to physically push himself each night to perform to thousands of people.

Watching the Serious Moonlight Tour film, one can see that Bowie is at the top of his game as a live performer.

Despite the upset of Vaughan’s absence, Carlos Alomar recollects that: “The concept for Serious Moonlight was really a big family, and I think it worked really, really well. There was a sense of an international community onstage, because the album had really hit the mark – it was a very happy time for him.”

Rojas agrees that: “The tour was a happy time for everyone; when we played the stadiums, it was mind-boggling. It was my first time doing so many, and David’s first time, too. You can’t describe what it feels like playing in front of 100,000 people. If I had a time machine, I’d gladly do it again.”

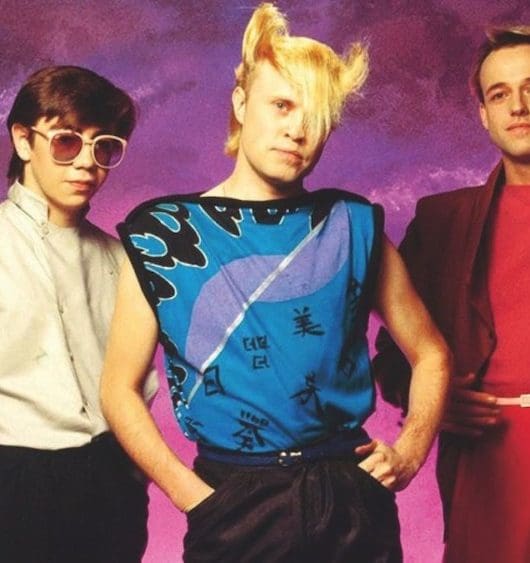

Similar to The Spiders From Mars outfits in their sense of otherworldly character (or perhaps more aptly Bowie’s earlier, wackier comic-book band, The Hype), each member of the Serious Moonlight band had their own distinct outfit – Carlos was (in Bowie’s words) “a prince”, while Carmine wore a sailor’s cap; Earl Slick was the incongruous denim-clad rocker, while the saxophone players were dressed as a Cossack, a mountaineer and a big-game hunter.

At the centre of it all was an increasingly dynamic besuited Bowie, who delivered incredible vocal performances night after night.

As Nicholas Pegg notes in The Complete David Bowie: “More than any previous Bowie tour, the set list was unashamedly a Greatest Hits package, aimed at acquainting the new mass audience with Bowie’s back catalogue.”

With only four tracks from Let’s Dance included, the sense that he was touring a new album was slight.

On a show in Toronto, Earl Slick stepped aside as – out of the shadows – Bowie’s former on- and off-stage musical partner Mick Ronson returned to perform The Jean Genie.

Ronson recalled in David Bowie: The Star Zone Interviews that: “I was playing Slick’s guitar, I had heard Slick play solos all night, so I decided not to play solos and I just went out and thrashed the guitar.

“I really thrashed the guitar, I was waving the guitar above my head and all sorts of things. It was funny afterwards because David said: ‘You should have seen Slick’s face…’ meaning he looked petrified. I had his prize guitar and I was swinging it around my head and Slick’s going ‘Waaaa… watch my guitar’, you know.

“I was banging into it and it was going round my head. Poor Slick. I mean, I didn’t know it was his special guitar, I just thought it was a guitar, a lump of wood with six strings!”

Reflecting on the tour, Carmine tells us that: “We were out for like a year, or something like that. And I do think it took its toll, definitely. For David, I think it was a lot to control. Performing to that volume of people who were there to see you individually must have been really mind-boggling. If he didn’t have a good team of sergeants and generals, I think it could have fallen apart. Thankfully, he did!”

Regardless of Bowie’s new status as a mainstream figure, and the apparent beginnings of a creative slump that would unfortunately come to dictate the shape of his work as the decade progressed, the Serious Moonlight Tour was an undeniable success that helped to spread Bowie’s stardom around the world.

Over a decade later, once he had returned to the fringes – though in a state of heady creative nourishment on the heels of his recent work with Brian Eno on 1995’s 1: Outside – he reflected in the pages of Interview magazine that: “I went mainstream in a major way with the song Let’s Dance. I pandered to that in my next few albums, and what I found I had done was put a box around myself. It was very hard for people to see me as anything other than the person in the suit who did Let’s Dance.”

In the there and then, Bowie was buoyed by his new worldwide fame, and sought to capitalise on his status with Let’s Dance’s hastily assembled follow-up.

However, for the David Bowie fans who’d found solace in Ziggy Stardust, innovation and promise in the Berlin trilogy, and an overt sense of awareness and belonging with Scary Monsters, his 1980s catalogue would increasingly detach itself from those worlds, and continue to chart a course directly for the ears of the general record-buying public.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!