Ultravox – album by album

By Jon O'Brien | March 13, 2023

We take a look through the albums of Ultravox, from their earliest days with John Foxx, to their last record – to date – from 2012…

We take a look through the albums of Ultravox, from their earliest days with John Foxx, to their last record – to date – from 2012…

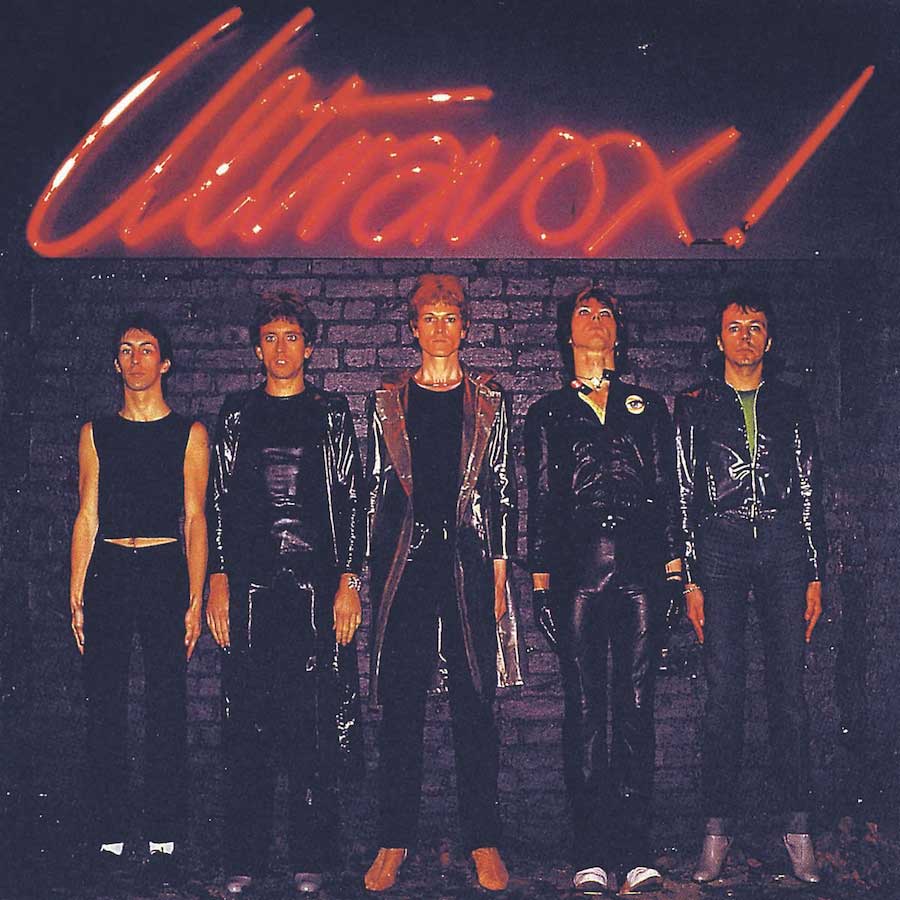

Ultravox!, 1977

First coming together in 1974, vocalist John Foxx, guitarist Stevie Shears, bassist Chris Cross, violinist Billy Currie and drummer Warren Cann didn’t have the most auspicious of starts.

Their first single, titled Ain’t Misbehavin’, was a Fats Waller cover that was commissioned, but embarrassingly then unused, by producers of a soft porn flick. And their attempts to rebrand themselves from Tiger Lily to The Damned were, unsurprisingly, thwarted by a then-unknown outfit fronted by Dave Vanian.

Even when they signed a deal with Island, renamed themselves Ultravox! – the exclamation mark a nod to krautrock pioneers Neu! – and duly bagged Brian Eno as co-producer, their fortunes failed to change.

Indeed, the general response to the quintet’s self-titled 1977 debut was about as animated as its mannequin-themed cover art, with neither the album nor dub reggae-inspired single Dangerous Rhythm troubling any kind of major chart.

Admittedly, Ultravox!, also notable for being Steve Lillywhite’s first significant production credit, wasn’t the easiest sell.

Inspired by the dystopian fiction of JG Ballard and William S. Burroughs, Foxx appeared to go out of his way to offend the London tourist board, poetically bemoaning about the loneliness, decay and all-round discontent of life in the capital across nine tracks, in his soon-to-be trademark sneer.

“Tottenham Court Road litter skitters in the wind,” he bellows on deliberately misspelled opener Sat’day Night In The City Of The Dead, while “Delightfully unpleasant with the foxy adolescents,” is how he describes a certain demographic on Wide Boys.

He even finds the time to take a potshot at London’s biggest musical export, The Rolling Stones, on the puntastic Life At Rainbow’s End (For All The Tax Exiles On Main Street).

The album’s sound was impossible to pigeonhole, too, lurching from the pop of the band’s youth (Slip Away) to new wave, glam rock, proto-punk and a haunting mood piece (My Sex) which essentially put the New Romantic wheels in motion.

The latter’s use of synths has since been hailed as a watershed moment but, on its release, it largely confounded those who couldn’t grasp the concept of thinking outside the guitar-bass-drums (and violins) box.

As Foxx would tell The Quietus: “Being ahead of your time is worse than being behind your time.”

Despite the general apathy that greeted the arrival of Ultravox!, this audacious statement of intent remains one of the most vital entries in the band’s back catalogue.

- Read more: Ultravox interview

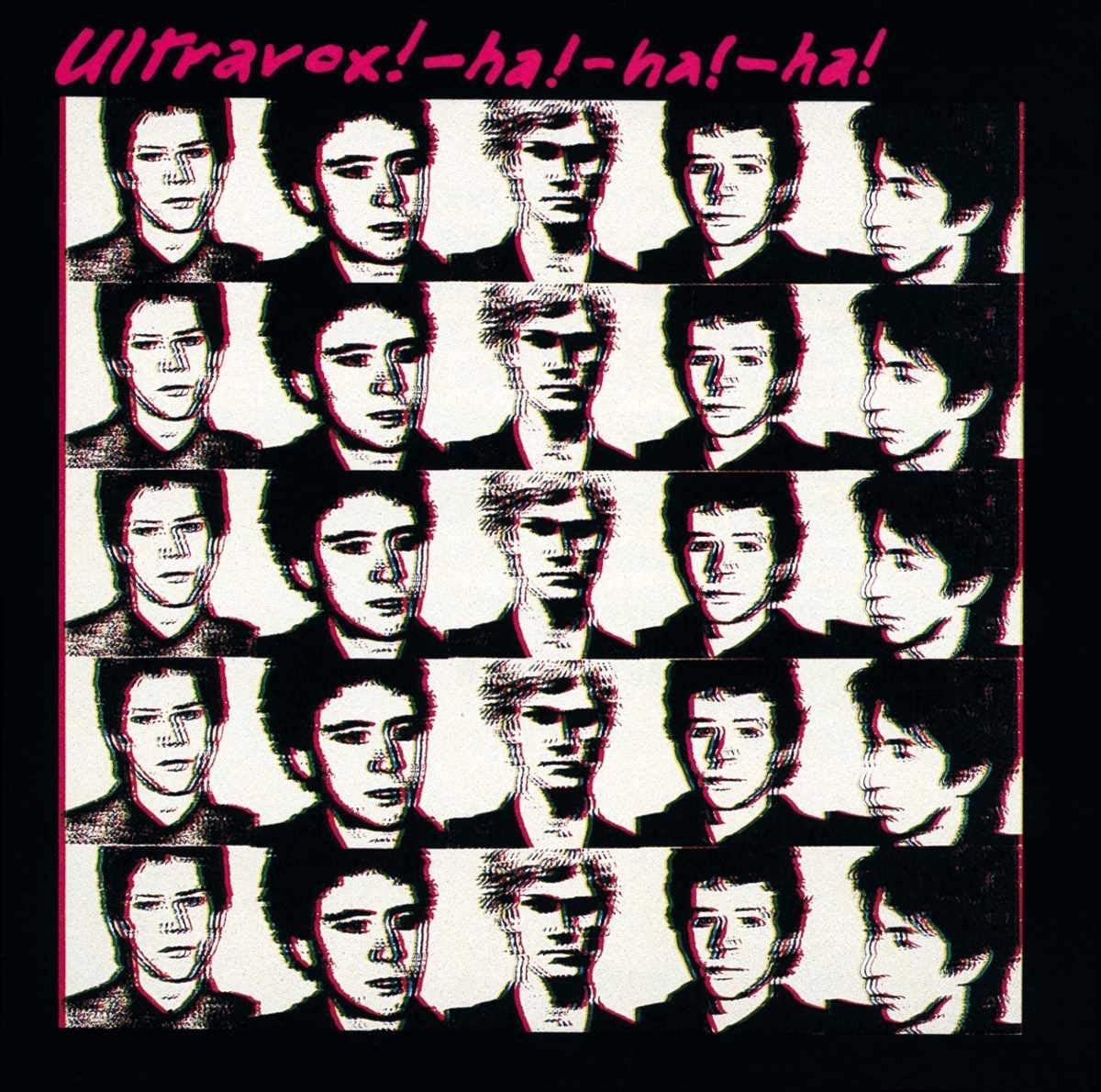

Ha!-Ha!-Ha!, 1977

“We were out to piss off as many people as possible,” remarked Currie in the liner notes for Ultravox!’s second album, Ha!-Ha-Ha!, issued just eight months after their debut LP.

ROckWrok, a grammatically-jumbled post-punk anthem featuring the line, “Come on, let’s tangle in the dark/ Fuck like a dog, bite like a shark” suggests that English teachers and conservative parents were top of the list.

Again with producer Lillywhite, the band were similarly abrasive, from the feedback-drenched cry of Fear In The Western World to the glam-tinged defiance of While I’m Still Alive, with Foxx’s caustic tones on the latter suggesting that he, too, had been gripped by the summer of Sex Pistols.

Yet there were also moments of strange beauty. Lifting its title from a French New Wave classic, the melancholic lament of closer Hiroshima Mon Amour allows Foxx to turn dreamlike crooner, Cann to showcase his newly-purchased Roland TR-77 drum machine and Gloria Mundi’s C.C. to steal the show with his wailing sax solo.

And while Distant Smile eventually explodes into life, it begins with a solemn piano instrumental that foreshadows Foxx’s future collaborations with Harold Budd.

Ha!-Ha!-Ha! sold as little as you’d expect from an LP with such antagonistic intentions. But as the sound of a band who obviously needed to get something out of their system, it’s a fascinating listen.

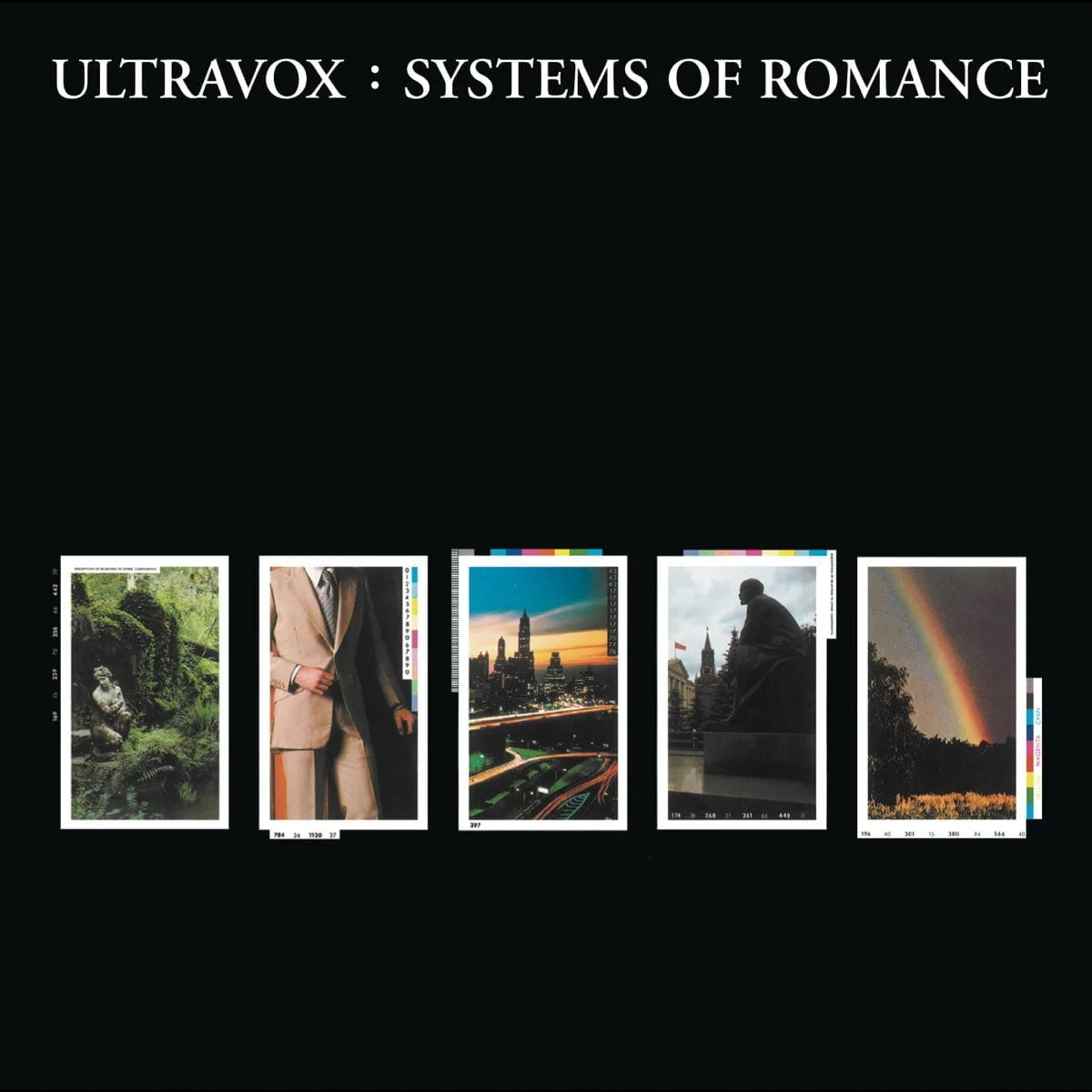

Systems Of Romance, 1978

Continuing their prolific work rate, Ultravox’s third album in less than 18 months was one of many milestones. It was their first (and last) to feature Robin Simon of one-time support act Neo: founding member Shears had exited in early 1978.

It was also their first since dropping the exclamation mark and the first of three records to feature the production talents of German studio wizard Conny Plank.

The latter infused Systems of Romance, named after his love of systems music, with the motorik rhythms and Teutonic electronics that he’d pioneered with major Ultravox inspirations Kraftwerk and Neu!

Meanwhile, Foxx, although still in disillusioned mode, decided to tone down the nihilism and embrace a poetic blend of introspection and surrealism: see “I’d like to glide/ In the long green light/ Of a July afternoon/ Sliding down a vague conversation” on the ebullient I Can’t Stay Long.

So, did this more pronounced sonic and lyrical shift finally give the late-70s perennial outsiders their mainstream breakthrough? Well, no.

Although it reportedly sold a creditable 20,000 copies, Island decided to cut their losses shortly after an Old Grey Whistle Test performance of opener Slow Motion, ironically a track Cann claimed perfectly encapsulated the way the band blended rock and synthesizer.

Nevertheless, this amalgamation still helped to shape Ultravox’s history and beyond. Foxx’s second solo LP, The Garden, took obvious cues from the record, most notably on the same-named leftover from the Systems Of Romance sessions.

It even convinced their soon-to-be new lead vocalist that the band was worth abandoning his journeyman career approach for. Outside of the ‘Vox’s revolving door policy, Gary Numan – who’d ask Currie to perform on 1979’s The Pleasure Principle – cited it as a key inspiration.

But you can hear traces of everyone from OMD and Teardrop Explodes to Duran Duran and The Cure in its 10 tales of 20th century dislocation.

In 2019, Foxx told Classic Pop he believes that Systems… is the ultimate Ultravox album, recorded at a time when they’d “consciously got rid of all the rock clichés” and each member was at the top of their game. If you prefer the group in the days they couldn’t get arrested, it’s hard to disagree.

- Read more: Ultravox – the complete guide

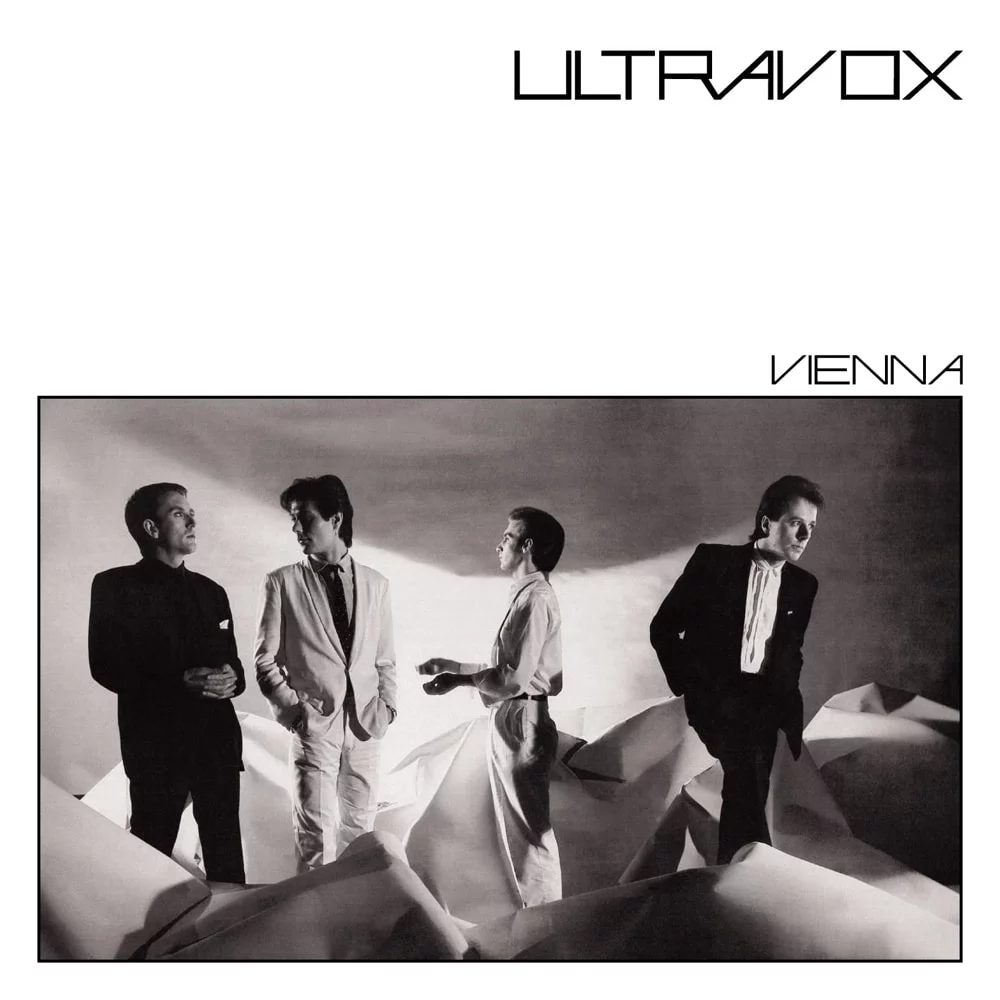

Vienna, 1980

Ultravox looked to have been dead and buried once they’d been dropped by Island and by Foxx, who jumped ship to pursue a typically esoteric solo career and, to a lesser extent, Simon, who joined Magazine. Instead, from a purely commercial perspective anyway, all this upheaval proved to be a blessing in disguise.

Replacement frontman Midge Ure – whose CV already included Thin Lizzy, Rich Kids and Visage – instantly revitalised the slimmed-down four-piece on an LP which not only attained that elusive chart success but also ushered in a whole new musical movement.

Admirers who had witnessed Tiger Lily’s no-frills glam-rock beginnings may have gasped at Vienna’s reliance on electronics, not to mention its deliberate sense of pomp and grandeur. But fans of the burgeoning New Romantic scene latched onto the album, and its title track in particular, sending both hurtling to within a whisker of No.1.

Vienna the song will, of course, be best-remembered for how it failed to reach pole position, with Joe Dolce’s culture-appropriating novelty hit Shaddap You Face providing one of the all-time chart injustices.

But more than 40 years on, and that moment the pencil-moustachioed Ure belts out “It means nothing to me” above those cascading classical keys still has the power to raise the hairs on the back of your neck.

But there’s more to Vienna the album than its eponymous near-miss. You can understand why Chrysalis offered a deal on the sole basis of Sleepwalk, a surging electronic pop number which gave the band their debut Top 40 hit.

You can also imagine the befuddlement of the casual Radio 1 listener on hearing opener Astradyne, a synth-prog instrumental which stretches past the seven-minute mark.

But with Conny Plank still on production duties, Vienna isn’t the roots-betraying affair its detractors (NME: “an album of gaudy, sometimes magnificent, but mostly hollow edifices”) claimed.

Post-punk anthems New Europeans and Passing Strangers could easily have escaped from Systems of Romance, while the anti-capitalist anthem Western Promise proved that societal downfall was still very much on their minds.

- Read more: Making Vienna

Rage In Eden, 1981

“There’s a starkness about it. An austere, mystical distance – a coldness to it but a coldness that kind of works.” Ure could have been describing any one of Ultravox’s LPs as a personal favourite in a 2015 interview with Rhino.

But he was, in fact, referring to 1981’s Rage in Eden, which thanks to Vienna’s monumental success forced the ‘Vox to deal with “difficult second album syndrome” on what was actually their fifth.

To combat any pressure, the quartet changed tack, heading into Plank’s Cologne studio without any material already written.

This more spontaneous approach appeared to inspire a more experimental one, too. If you’re wondering why the title track’s chorus seems strangely familiar, it’s because it’s also the chorus from I Remember (Death In The Afternoon) played in reverse.

And in a further sign of Ultravox’s classical tendencies, Accent on Youth, The Ascent and Your Name (Has Slipped My Mind Again) are all segued together in one long suite.

Rage In Eden didn’t produce another monolithic Vienna-esque hit like Chrysalis were no doubt hoping for (“They used to come up and say, ‘You know, ‘Paris’ is a really good city name,” Ure added to Rhino).

The galvanising drums, staccato bass and vitriolic lyrics (“And those who sneer will fade and die/ And those who laugh will surely fall”) of lead single The Thin Wall climbed no higher than No.14 in the UK, while ghostly follow-up The Voice peaked two places lower.

But despite reuniting with Plank, Ultravox never seemed interested in striking lightning twice.

Although Rage In Eden shares a sparseness with their ode to the Austrian capital, the cavernous slow-motion beats and glacial piano chords of closing track Your Name (Has Slipped My Mind Again) certainly don’t seem designed for a chart battle with a fake Italian cabaret singer.

Likewise, the title track, a similarly desolate anthem of doom which ends with a burst of dissonant radio-wave feedback.

Perhaps mindful of those sell-out accusations, the Top Of The Pops regulars instead delivered an album that was almost as uncompromising as their days playing in front of one and man his dog.

Quartet, 1982

Having appeared to deliberately veer away from the mainstream with their first post-Vienna record, Ultravox then wholeheartedly embraced it with their second. Out went cult favourite Plank and in came the most successful producer in pop history.

Encouraged to work with the four-piece by his teenage daughter, George Martin was left impressed by his unlikely detour into New Romantic territory.

Indeed, the fifth Beatle, who’d just worked with the likes of Cheap Trick, UFO and Little River Band, described Ure and co as the “most musical group I have come across in years.”

Unfortunately, the band themselves weren’t quite as enthused about the experience. Cann would later go on to say the band were underwhelmed by a distinct lack of sonic experimentation in the studio.

It’s true that 1982’s Quartet, released just six months after Ure first dipped his toe into solo waters with a cover of The Walker Brothers’ No Regrets, smooths off many of the ‘Vox’s cutting edges.

Reap The Wild Wind, a song with no real lyrical meaning, was blatantly recorded with one eye on the other side of the Atlantic: the track subsequently became their first and only appearance on the Billboard Hot 100, making it to No.71. And there’s a notable lack of proggy instrumentals and their USP, Currie’s piercing viola.

Yet despite cosying up to the pop establishment, it’s still not quite the full-on AOR-fest that some disgruntled fans purported.

We Came To Dance continues Cann’s penchant for wonderfully creepy spoken-word interludes, for example.

Meanwhile, the baroque pop balladry of Visions In Blue and Hymn, a diatribe against the abuse of political power which borrows its melodic hook from Ure associates Zones’ Mourning Star (released on Arista in 1979), are worthy of joining the band’s top-tier canon.

However, despite Quartet being the only Ultravox album to spawn four Top 20 singles in the UK charts, it remains the least essential long-player from their imperial phase.

Lament, 1984

Perhaps burned by sell-out accusations from their collaboration with George Martin, Ultravox chose to produce their ’84 follow-up themselves.

It proved a re-energising move. Lament spawned their second-biggest UK hit, Dancing With Tears In My Eyes which, thanks to Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Two Tribes, was only the year’s second-biggest hit about impending nuclear doom – its video also appeared to predict the Chernobyl disaster two years early.

As well as addressing Britain’s handover of Hong Kong to communist China (White China) and political disillusionment (Heart Of The Country), this seventh LP also found the ’Vox getting unusually personal, with both A Friend I Call Desire and When The Time Comes ostensibly break-up anthems.

Accompanied by a windswept promo filmed in the Outer Hebrides, lead single One Small Day and Man Of Two Worlds, boasting some evocative Gaelic vocals from Mae McKenna, suggested that the band were keen to muscle in on U2’s Celtic rock territory, too.

Yet despite the heavier reliance on guitars, Lament’s true highlight was its synth-based title track, a beautifully sombre ballad that had more in common with the electro-miserablism of Depeche Mode than the chest-beating antics of Bono and co.

As the final album with their chart-bothering line-up, this was a creditable, if occasionally derivative, swansong.

U-Vox, 1986

To say that the two-year gap between Lament and its 1986 follow-up was eventful would be an understatement, something the latter was unfortunately lacking.

Not only did Ure help organise both the UK’s best-selling single ever and most iconic live show in pop history, he also launched his solo career proper. On top of that, founding member Cann was sacked due to that age-old reason of ‘creative differences’.

The drummer, replaced by Big Country’s Mark Brzezicki, no doubt counted this dismissal as a lucky escape on hearing his former outfit’s eighth album. U-Vox was apparently nicknamed ‘The Dreaded Pink Thing’ by fans due to its neon-coloured artwork.

Unfortunately its musical accompaniment was almost as garish. Indeed, it’s difficult to believe that its nine tracks were co-produced by Conny Plank, the German who helped mastermind the band’s transition from post-punk unknowns to synth-pop household names.

U-Vox actually begins relatively promisingly, with the big-lunged vocals of Carol Kenyon (Heaven 17’s Temptation) and brassy horns of jazz-funk trio Beggar & Co on Same Old Story proving that Ultravox could combine the glossy with the grandiose.

Their other collaborations, on the other hand, explain why Ure once revealed the album should have been titled ‘U-Bend’ as it should have been flushed down the drain.

It’s tough to determine what’s more ham-fisted on second single All Fall Down, the attempt at Celtic folk which makes Irish music stalwarts The Chieftains resemble a pub band, or the moon-in-June lyrics that detract from the well-meaning anti-war sentiment (“Well look in the mirror and what do you see/ An American, Russian, a soldier or me”). The idiosyncratic musings of the Foxx era had never seemed so distant.

Further proof that Ultravox had lost their way arrives on closer All In One Day, a self-indulgent reflection on Live Aid orchestrated by a subtle-as-a-sledgehammer George Martin, and the bombastic fusion of sax and hair metal riffs on Moon Madness.

U-Vox completed the band’s run of five consecutive Top 10 albums but, unlike its predecessors, failed to spawn a Top 20 hit. It also proved to be the nail in their seven-year coffin.

Revelation, 1993

“I think some of the Revelation album is absolute crap,” Currie admitted 13 years after his ill-advised attempt to extend Ultravox’s legacy without any other original members. Some would argue that this typically honest reassessment is still way too generous.

Indeed, whereas the band were once considered pioneers, their ninth LP sounded hopelessly dated. No Turning Back and Unified both strive for anthemic status but end up resembling failed A Song For Europe entries, while I Am Alive is the kind of fist-pumping schlock you could imagine David Hasselhoff belting out on a crane above the fallen Berlin Wall.

Currie’s appointment of Tony Fennell, who’d played bass for Edwin Starr and written for Kenny Thomas, essentially hampered the revival before it began.

Should Ultravox stage a jukebox musical, then his theatrical vocals would no doubt play well to the cheap seats. On record, however, they sound overwrought to the point of parody.

Revelation isn’t entirely without merit. True Believer is an intriguing synth-funk number which takes aim at the crazy world of televangelism.

And things could actually have been worse. Currie and Fennell duly announced their partnership with a karaoke cover of Vienna that was so anodyne it left you longing for a guest appearance from Joe Dolce…

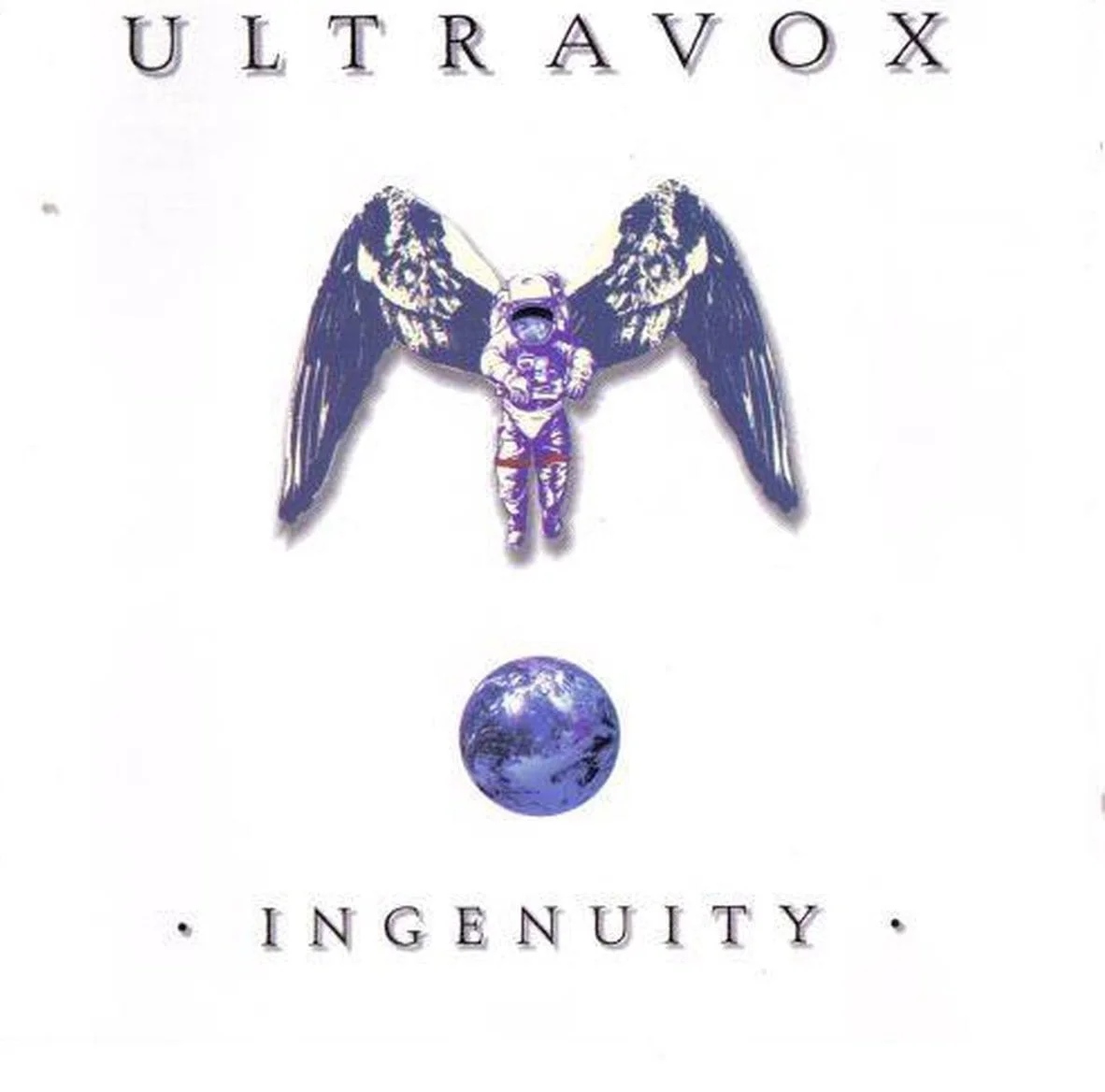

Ingenuity, 1994

Ultravox Version 6.0 saw Currie dispense with the duo approach in favour of a younger full band that included guitarist Vinny Burns, bassist Gary Williams, drummer Tony Holmes and, notably, new lead vocalist Sam Blue.

The latter, whose list of collaborators includes Madness, Montserrat Caballé and The Streets (he duets with Mike Skinner on Dry Your Eyes), is much more suited to the frontman role, his gutsier delivery steering Ingenuity away from the MOR hell of its predecessor.

Although not quite living up to its title, closer Majestic was their first instrumental since 1980’s Astradyne, while the propulsive lead single, There Goes A Beautiful World, and throbbing synth-bass of Give It All Back proved that Currie hadn’t forgotten what made the Ure era so fruitful.

Unfortunately, Ingenuity also gives in to some of latter-day Ultravox’s worst excesses. Take a shot every time you hear an air guitar-friendly solo and you’ll be on the floor by half-way. While no embarrassment, this could still be filed under ‘entirely unnecessary.’

Brilliant, 2012

Ultravox were always setting themselves up for a fall by naming their first album in 18 years – and their first with the core line-up in 28 – after such a superlative. Indeed, ‘Underwhelming’ would have been a more accurate title.

Ure, Cann, Cross and the ever-present Currie were inspired to head back into the studio following a triumphant reunion tour. Yet there’s little on 2012’s Brilliant to reflect this.

In fact, with its dreary quasi-showtunes, which suggest that Ure was angling for a role in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s next dirge (Remembering), meandering prog (Contact) and patience-testing ballads (One, Fall), the band’s 11th album is more funereal than celebratory.

Occasionally, the more vibrant production talents of Stephen Lipson (Annie Lennox, Paul McCartney) shine through, as on the shoegazey Flow and Moroder-esque Rise. But even Ure, whose whispered, lethargic vocals are light years away from the passion he brought to Ultravox’s heyday, sounds rather bored by it all.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!